A New Tern (Sterna) Breeding Record for Hawaii!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

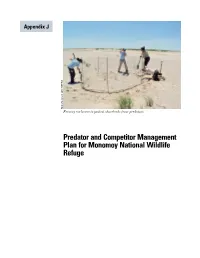

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

WHITE TERN Gygis Alba

WHITE TERN Gygis alba Other: Common White-Tern (1998-2000) G.a. candida (breeding) Fairy Tern, Manu-o-ku G.a. microrhyncha (vagrant) breeding visitor, indigenous; vagrant Three taxonomic groups of White Tern have been recognized, occurring in the tropical s. Atlantic Ocean (G.a. alba group), the Marquesas and Kiribati Is (microrhyncha group), and throughout the remainder of the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, including Micronesia, Wake and Johnston atolls (Amerson and Shelton 1976, Rauzon et al. 2008), and the Hawaiian Islands (candida group). Various ornithologists consider these groups to comprise two or three different species (Pratt et al. 1987, AOU 1998) although, based on reported hybridization between microrhyncha and candida in the Marquesas Is (Holyoak and Thibault 1976), Higgins and Davies (1996) and the AOU (1998) consider these as subspecies groups within a single species. Olson (2005) has recently made a good case for treating microrhyncha and candida as separate species but molecular evidence suggests they should remain a single species (Yeung et al. 2009). See Niethammer and Patrick (1998) for more information on the natural history and biology of this species in the Hawaiian Islands. The great majority of White Terns breeding in the Hawaiian Islands are found in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, where they occur on every island group, and number about 25,000 pairs in total population size (Table). The largest numbers by far are found on Midway, where the maturation of Casuarina trees providing nesting sites (cf. Fisher and Baldwin 1946, Rauzon and Kenyon 1984, Harrison 1990, Rauzon 2001; E 16:28-29) has lead to a large population increase, from only a few at the turn of the 20th century (Bryan 1906, Bartsch 1922) to about 3,000 in 1938 (Hadden 1941), to ~20,000 pairs in the mid 2010s. -

Class Three: Breeding

Class Three: Breeding WHERE DO SEABIRDS LAY THEIR EGGS? Nest or no nest? • Some species use no nesting material. E.g., the white tern lays a single egg on an open branch. • Some species use a very little bit of nesting material. E.g., the tufted puffin may use a few pieces of grass and a couple of feathers. • Some species build more substantial nests. E.g. kittiwakes cement their nests onto small cliff shelves by trampling mud and guano to form a base. And, some cormorants build large nests in trees from sticks and twigs. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 1 White tern • Also called fairy tern. • Tropical seabird species. • Lays egg on branch or fork in tree. No nest. • Newly hatched chicks have well developed feet to hang onto the nesting-site. White Tern. © Pillot, via Creative Commons. On the coast or inland? • Most seabird species breed on the coast and offshore islands. • Some species breed fairly far inland, but still commute to the ocean to feed. E.g., kittlitz’s murrelets nest on scree slopes on coastal mountains, and parents may travel more than 70km to their feeding grounds. • Other species breed far inland and never travel to the ocean. E.g., double crested cormorants breed on the coast, but also on lakes in many states such as Minnesota. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 2 NESTING HABITAT (1) Ground Some species breed on the ground. These species tend to breed in areas with little or no predation, such as offshore islands (e.g., terns and gulls) or in the Antarctic (e.g., penguins, albatross). -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Hawaiian Monk Seal Pupping Locations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands'

Pacific Science (1990), vol. 44, no. 4: 366-383 0 1990 by University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Hawaiian Monk Seal Pupping Locations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands' ROBINL. wESTLAKE2'3 AND WILLIAM G. GILMARTIN' ABSTRACT: Most births of the endangered Hawaiian monk seal, Monuchus schuuinslundi, occur in specific beach areas in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Data collected from 1981 to 1988 on the locations of monk seal births and of the first sightings of neonatal pups were summarized to identify preferred birth and nursery habitats. These areas are relatively short lengths of beach at the breeding islands and have some common characteristics, of which the pri- mary feature is very shallow water adjacent to the shoreline. This feature, which limits access by large sharks to the water used by mother-pup pairs during the day, should enhance pup survival. THE HAWAIIANMONK SEAL, Monachus at Kure Atoll, Midway Islands, and Pearl and schauinslundi, is an endangered species that Hermes Reef. Some of the reduced counts occurs primarily in the Northwestern Ha- were reportedly due to human disturbance waiian Islands (NWHI) from Nihoa Island (Kenyon 1972). Depleted also, but less drama- to Kure Atoll (Figure 1). The seals breed at tically during that time, were the populations these locations as well, with births mainly oc- at Lisianski and Laysan islands. Although curring from March through June and peaking one could speculate that a net eastward move- in May. Sightings of monk seals are frequent ment of seals could account for the increase around the main Hawaiian Islands and rare in seals at FFS along with the reductions at at Johnston Atoll, about 1300 km southwest the western end, the available data on resight- of Honolulu (Schreiber and Kridler 1969). -

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

Notes on the Birds Peculiar to Laysan Island, Hawaiian Group

3S4 V'lS,•ER,Birds of La),san Island. FL AukOct. NOTES ON THE BIRDS PECULIAR TO LAYSAN ISLAND, HAWAIIAN GROUP. 1 BY WALTER K. FISHER. •ølates x_,r_,r-x WE DOnot naturally associateland birds with tiny coral atolls in tropicalseas. It is thereforea strangefact that sucha diminu- tive island as Laysan, and one so remote from continentalshores, should harbor no less than five peculiar species: the Laysan Finch (]klespiza cantans) and Honey-eater (I-Iima•ione freethi), both • drepanidid' birds, the Miller Bird (.4crocefihalusfamiliaris), the LaysanRail (?orzanulapalmeri),and lastly the LaysanTeal (•tnas laysanensis).I usethe term ' land birds' loosely,in con- tradistinctionto sea-fowl,multitudes of which breed here through- out the year. The presenceof these speciesis all the more remarkablebecause none appear on neighboringislands, more or less distant, someof which are very similar to Laysan in structure and flora. Reachingout towardJapan from the main Hawaiian group is a long chainof volcanicrocks, atolls,sand-bars• and sunkenreefs, all insignificantin size and widely separated. The last islet is fully two thousandmiles from Honolulu and about half-way to Yokohama. Beginningat the east,the more importantmembers of this chain are: Bird Island and Necker (tall volcanicrocks), French Frigate Shoals, Gardner Rock, Laysan, Lisiansky, Mid- way, Cure, and Motell. Laysanis eighthundred miles northwest- by-westfrom Honolulu,and is perhapsbest knownas beingthe home of countless albatrosses. We sightedthe island early one morning in May, lying low on the horizon,with a great cloud of sea-birdshovering over it. On all sides the air was lively with terns, albatrosses,and boobies, •These notes were made during a visit of the Fish Commissionsteamer ' Albatross' to Laysan, May 17 to 23, 19o2, and are abridged from a more extendedreport on the avifauna of the i•land• to appearin the Bulletin of the U.S. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

The Birds of Lido Beach

The Birds of Lido Beach An introduction to the birds which nest on and visit the beaches between Long Beach and Jones Inlet, with a special emphasis on the NYS endangered Piping Plover Paul Friedman Ver. 1.1 Best if viewed in full screen mode 1 Featured Birds Nest on the Beach Migrants* • Piping Plovers • Sanderlings • American Oystercatchers • Dunlins • Common Terns • Semipalmated Plovers • Least Terns • Black Skimmers * These three are just a few of the many migrants which use our beach as a layover 2 The Migrants Nest in the far north (Greenland , sub-arctic, etc.) – seen in Spring and mid/late Summer as they migrate to and from their nesting grounds Probe for food in the wet sand along the ocean’s edge • Sanderlings - most numerous of the three - can be seen in large groups in flight and running back and forth probing the wet sand left by a receding wave • Dunlins – characterized by long drooping bill – can be found with Sanderlings • Semipalmated Plovers– similar to Piping Plover in size and shape; and have distinctive black bands on the neck and forehead. Sanderlings Dunlins Semipalmated Plovers 3 Sanderlings Acrobatic, precision fliers; seen in large flocks. The entire flock can Note black legs and straight black bill turn on a dime; a required skill when evading a falcon. Large groups chase receding waves to…… … probe the wet sand for food 4 Dunlins Note droop in bill. Black belly is breeding plumage. Probing the wet sand for food Often found mixed in with Sanderlings At ocean’s edge 5 Semipalmated Plovers Note black forehead and black neck band Pictured here with its close cousin, the Piping Plover 6 Slurping a marine worm as one might a strand of spaghetti Taking flight The Lido Beach Nesting Birds o All nest in scrapes in sand between high tide and dunes o Two strategies – nest in colonies or nest in solitary pairs • Colonial Nesting Birds 1. -

Potential Effects of Sea Level Rise on the Terrestrial Habitats of Endangered and Endemic Megafauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Vol. 2: 21–30, 2006 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Printed December 2006 Previously ESR 4: 1–10, 2006 Endang Species Res Published online May 24, 2006 Potential effects of sea level rise on the terrestrial habitats of endangered and endemic megafauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Jason D. Baker1, 2,*, Charles L. Littnan1, David W. Johnston3 1Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 2570 Dole Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 2University of Aberdeen, School of Biological Sciences, Lighthouse Field Station, George Street, Cromarty, Ross-shire IV11 8YJ, UK 3Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, 1000 Pope Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA ABSTRACT: Climate models predict that global average sea level may rise considerably this century, potentially affecting species that rely on coastal habitat. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) have high conservation value due to their concentration of endemic, endangered and threatened spe- cies, and large numbers of nesting seabirds. Most of these islands are low-lying and therefore poten- tially vulnerable to increases in global average sea level. We explored the potential for habitat loss in the NWHI by creating topographic models of several islands and evaluating the potential effects of sea level rise by 2100 under a range of basic passive flooding scenarios. Projected terrestrial habitat loss varied greatly among the islands examined: 3 to 65% under a median scenario (48 cm rise), and 5 to 75% under the maximum scenario (88 cm rise). Spring tides would probably periodically inun- date all land below 89 cm (median scenario) and 129 cm (maximum scenario) in elevation. Sea level is expected to continue increasing after 2100, which would have greater impact on atolls such as French Frigate Shoals and Pearl and Hermes Reef, where virtually all land is less than 2 m above sea level.