Prey Delivered to Roseate and Common Tern Chicks; Composition and Temporal Variability Carl Safina, Richard H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridled Tern Breeding Record in the United States

SCIENCE areamore closely, and quickly locat- ed a downy Bridled Tern chick crouched under one of the rocks which was usedas a perchby the BRIDLEDTERN adult. We have accumulated addi- tionalrecords of nestingat thissite in subsequentyears. BREEDING BridledTerns breed throughout the Bahamas and the Greater and LesserAntilles, and occur commonly offshoreFlorida and regularlyoff RECORDIN THE other southeasternstates, but this is thefirst evidence of breedingreport- edfor NorthAmerica north of Quin- UNITEDSTATES tana Roo on the Yucatan Peninsula (Howell et al. i99o). In this note we describe the islet, the Roseate Tern colony,and the BridledTern nest byPyne Hoffman, site,and compare the nesting habitat of these terns to that used in the Ba- AlexanderSprunt IV, hamas. The FloridaKeys are flankedto PeterKalla, and Mark Robson the eastand south by a line of coral reefsparalleling the main keysat a distance of 6 to i2 kilometers. The best-developed(and some of the On themorning of July •5, •987, two Terns(Sterna anaethetus) flying low shallowest)reefs occur along the reef of us(Sprunt and Hoffman) visited a overthe colony.One of theseterns margin,adjacent to thedeep water of RoseateTern (Sterna dougallih colony sat for extendedperiods on coral the FloridaStraits. The tern colony on a small coral rubble islet on Peli- rocksin the northeasternpart of the occupiesan isletof approximately canShoal, south of BocaChica Key, isletand circled, calling softly when one-fourthhectare composed of coral MonroeCounty, Florida. During in- we approached.We returnedto the rubble and sand located on a shallow spectionwe observedfour Bridled island that afternoon to examine the sectionof the fringingreef called Bridled Tern on Pelican Shoal. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

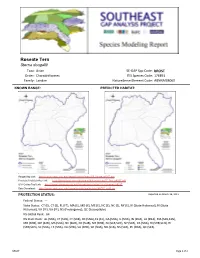

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Brost Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM08060

Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bROST Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM08060 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bROST.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bROST.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bROST Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bROST_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (E), CT (E), FL (FT), MA (E), MD (X), ME (E), NC (E), NC (E), NY (E), RI (State Historical), RI (State Historical), VA (LE), VA (LE), NS (Endangered), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G4 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), CT (S1B), CT (S1B), DE (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), IL (SNA), IN (SNA), LA (SNA), MA (S2B,S3N), MD (SHB), ME (S2B), MS (SNA), NC (SUB), NC (SUB), NH (SHB), NJ (S1B,S1N), NY (S1B), PA (SNA), RI (SHB,S1N), RI (SHB,S1N), SC (SNA), TX (SNA), VA (SHB), VA (SHB), WI (SNA), NB (S1B), NS (S1B), PE (SNA), QC (S1B) bROST Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 US Dept. -

Species Assessment for Roseate Tern

Species Status Assessment Class: Birds Family: Laridae Scientific Name: Sterna dougallii Common Name: Roseate tern Species synopsis: The North Atlantic population of roseate tern breeds along the Atlantic Coast from the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence southward to New York; this population is federally endangered. A separate population breeds in the Caribbean; this population is federally threatened. As colonies in Virginia and New Jersey became extirpated, these two populations, both S. d. dougallii, have been moving farther from one another, since the 1930s. The North Atlantic population rebounded in the early 1900s following protection from hunting and peaked in the mid-1970s. Both the number of colonies and the number of breeding pairs have dropped since then. In New York, all colonies—historic and current—are on Long Island, with the vast majority of pairs (99% in 2010) nesting at Great Gull Island. Great Gull Island is the largest of only three primary colonies in the Northeast, resulting in an elevated risk of extirpation due to stochastic events. Nesting occurs in a variety of habitats including marshes, rocky islands, and open sand. I. Status a. Current and Legal Protected Status i. Federal ____Endangered______________________ Candidate? __N/A__ ii. New York ____Endangered; SGCN_________________________________________ b. Natural Heritage Program Rank i. Global ____G4_______________________________________________________________ ii. New York ____S1B_______________________ Tracked by NYNHP? __Yes___ 1 Other Rank: Partners in Flight – Priority IB The North Atlantic population is federally endangered while the Caribbean population is federally threatened. Status Discussion: Currently, the Northeast population hovers at about 4,300 pairs (1,697 in MA in 2001) (Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife 2005). -

East Atlantic) Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii (2021-2030

International (East Atlantic) Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii (2021-2030) With the financial support of the European Union’s LIFE Nature Programme International (East Atlantic) Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the roseate tern Sterna dougallii (2021-2030) Final approved version LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394 May 2021 Produced by The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) Prepared in the framework of the Roseate Tern LIFE Project (LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394) coordinated by the RSPB in partnership with BirdWatch Ireland and the North Wales Wildlife Trust and co- financed by the European Union LIFE Nature Programme www.roseatetern.org 1 Adopting Framework: European Union (EU) Compiled by: Daniel Piec and Euan Dunn RSPB, The Lodge, Potton Road, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL List of contributors: FR: Bernard Cadiou, Yann Jacob, Olivier Patrimonio IE: Brian Burke, Andrew Butler, Tony Murray, Stephen Newton, David Tierney GH: Dickson Agyeman, Thomas Gyimah, Solomon Kenyenso, Eric Lartey, Yaa Ntiamoa- Baidu PT: Julia Almeida, Vanda Carmo, Maria Magalhães, Sol Heber, Veronica Neves, Małgorzata Pietrzak, Tânia Pipa, Pedro Raposo, Carla Silva (LIFE IP Azores Natura – LIFE17 IPE/PT/00010) UK: Ibrahim Alfarwi, Richard Berridge, Mark Bolton, Vivienne Booth, Richard Caldow, Adrian del Nevo, Paul Insua-Cao, Leigh Lock, Chantal Macleod-Nolan, Paul Morrison, Martin Perrow, Norman Ratcliffe, Chris Redfern, Karen Varnham Other: Geoffroy Citegetse, Ian Nisbet This plan uses evidence-based guidance principles. The following databases were checked on 11.03.2021: Conservation Evidence www.conservationevidence.com, the library of systematic reviews of Collaboration for Environmental Evidence https://environmentalevidence.org and the CEE Database of Evidence Reviews (CEEDER) database https://environmentalevidence.org/ceeder (using search terms “tern” and “seabirds”). -

Tracking Offshore Occurrence of Common Terns, Endangered Roseate Terns, and Threatened Piping Plovers with VHF Arrays Appendices A-K

OCS Study BOEM 2019-017 Tracking Offshore Occurrence of Common Terns, Endangered Roseate Terns, and Threatened Piping Plovers with VHF Arrays Appendices A-K US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs OCS Study BOEM 2019-017 Tracking Offshore Occurrence of Common Terns, Endangered Roseate Terns, and Threatened Piping Plovers with VHF Arrays April 2019 Authors: Pamela H. Loring, US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Division of Migratory Birds Peter W.C. Paton, Department of Natural Resources Science, University of Rhode Island James D. McLaren, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Science and Technology Branch Hua Bai, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Ramakrishna Janaswamy, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Holly F. Goyert, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Environmental Conservation Curtice R. Griffin, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Environmental Conservation Paul R. Sievert, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Environmental Conservation Prepared under BOEM Intra-Agency Agreement No. M13PG00012 By US Department of Interior US Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Migratory Birds 300 Westgate Center Dr. Hadley, MA 01035 US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs Appendix A Comparing Satellite and Digital Radio Telemetry to Estimate Space and Habitat Use of American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus) in Massachusetts Pamela H. Loring1, Curtice R. Griffin2, Paul R. Sievert2, and Caleb S. Spiegel1 1U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Birds, Northeast Region, 300 Westgate Center Drive, Hadley, Massachusetts, 01035, USA 2Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 160 Holdsworth Way, Amherst, Massachusetts, 01003, USA Citation: Loring PH, Griffin CR, Sievert PR, Spiegel CS. -

Background Document for Roseate Tern (Sterna Dougallii)

Background Document for Roseate tern Sterna dougallii Biodiversity Series 2009 OSPAR Convention Convention OSPAR The Convention for the Protection of the La Convention pour la protection du milieu Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic marin de l'Atlantique du Nord-Est, dite (the “OSPAR Convention”) was opened for Convention OSPAR, a été ouverte à la signature at the Ministerial Meeting of the signature à la réunion ministérielle des former Oslo and Paris Commissions in Paris anciennes Commissions d'Oslo et de Paris, on 22 September 1992. The Convention à Paris le 22 septembre 1992. La Convention entered into force on 25 March 1998. It has est entrée en vigueur le 25 mars 1998. been ratified by Belgium, Denmark, Finland, La Convention a été ratifiée par l'Allemagne, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, la Belgique, le Danemark, la Finlande, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, la France, l’Irlande, l’Islande, le Luxembourg, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom la Norvège, les Pays-Bas, le Portugal, and approved by the European Community le Royaume-Uni de Grande Bretagne and Spain. et d’Irlande du Nord, la Suède et la Suisse et approuvée par la Communauté européenne et l’Espagne. Acknowledgement This report has been prepared by Dr Nigel Varty and Ms Kate Tanner for BirdLife International as the lead party for the Roseate Tern. Photo cover page: Roseate tern, Wikipedia Contents Background Document for Roseate te rn Sterna dougallii ................................................................3 Executive Summary ...........................................................................................................................3 -

Caribbean Roseate Tern and North Atlantic Roseate Tern (Sterna Dougallii Dougallii)

Caribbean Roseate Tern and North Atlantic Roseate Tern (Sterna dougallii dougallii) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photo Jorge E. Saliva U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Caribbean Ecological Services Field Office Boquerón, Puerto Rico Northeast Region New England Field Office Concord, New Hampshire September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Reviewers............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology........................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Background............................................................................................................. 2 1.3.1 FR Notice………………………………………………………………… 2 1.3.2 Listing history……………………………………………...…………….. 2 1.3.3 Associated rulemakings………………………………………………….. 3 1.3.4 Review history…………………………………………………………… 3 1.3.5 Recovery Priority Number………………………………………….……. 3 1.3.6 Recovery plans…………………………………………………………… 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment policy................................ 3 2.1.1 Is the species under review a vertebrate?................................................... 4 2.1.2 Is the DPS policy applicable?..................................................................... 4 ENDANGERED NORTHEAST POPULATION 2.2 Recovery Criteria..................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Does the species have a -

Human Harvest, Climate Change and Their Synergistic Effects Drove the Chinese Crested Tern to the Brink of Extinction

Global Ecology and Conservation 4 (2015) 137–145 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Human harvest, climate change and their synergistic effects drove the Chinese Crested Tern to the brink of extinction Shuihua Chen a,∗, Zhongyong Fan a, Daniel D. Roby b, Yiwei Lu a, Cangsong Chen a, Qin Huang a, Lijing Cheng c, Jiang Zhu c a Department of Life Science, Zhejiang Museum of Natural History, Hangzhou, 310014, China b U.S. Geological Survey-Oregon Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA c Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100029, China article info a b s t r a c t Article history: Synergistic effect refers to simultaneous actions of separate factors which have a greater Received 24 June 2015 total effect than the sum of the individual factor effects. However, there has been a Accepted 26 June 2015 limited knowledge on how synergistic effects occur and individual roles of different drivers Available online 3 July 2015 are not often considered. Therefore, it becomes quite challenging to manage multiple threatening processes simultaneously in order to mitigate biodiversity loss. In this regard, Keywords: our hypothesis is, if the traits actually play different roles in the synergistic interaction, Synergistic effect conservation efforts could be made more effectively. To understand the synergistic effect Species endangerment Human harvest and test our hypothesis, we examined the processes associated with the endangerment of Climate change critically endangered Chinese Crested Tern (Thalasseus bernsteini), whose total population Chinese Crested Tern number was estimated no more than 50. -

NOTES on the SEA-BIRDS of BRAVA. by MEW NORTH,MBOD I

NOTES ON THE SEA-BIRDS OF BRAVA. By M. E. W. NORTH,M.B.O.D I.-INTRODUCTION. The town of Brava is on the south-east coast of ex-Italian Somaliland, mid-way between Mogadishu and Kismayu. The coast off Brava is by no means rich in islands suitable for sea-birds, but four are utilized. A description of these islands, working south-west, follows:- (1) Chilani.-This adjoins the coast, from which it can be reached on foot at low tide, by means of a reef. It is a conical, grass• covered islet, perhaps sixty yards in diameter,' crowned by a beacon, with small cliffs on three sides. Roseate Terns (S. dougallii) nest here. (2) Maginnis.-A mile south-west of Brava, the beach curves out to a low spit, where a mosque is situated. This is Mosque Point, a favourite resting-place for terns. A couple of hundred yards from the point, there is a string of coral boulders on a base that drles out at low tide, called Maginnis. Sooty Gulls (L. hemprichii) and Roseate Terns nest on the tops of these boulders. (3) Mnara.-An islet three miles south-west from Brava, similar in size and shape to Chilani, accessible at low tide. An ancient watch• tower is built on the summit. Sooty Gulls nest on outlying boulders. (4) EI Bakr.-An islet ten miles south-west of Brava, covered with rough undergrowth and grass. It adjoins a sandy point. from which it can be reached at low tide. A special visit was made to this island on August 10, which proved disappointing, since there were no resident sea-birds. -

Roseate Tern (Sterna Dougallii) the Birds Of

Roseate Tern — Birds of North America Online From the CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY and the AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION. Search Home Species Subscribe News & Info FAQ Already a subscriber? Sign in Don't have a subscription? Subscribe Now Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii Issue No. 370 Order CHARADRIIFORMES – Family LARIDAE Authors: Gochfeld, Michael, Joanna Burger, and Ian C. Nisbet Articles Multimedia References Articles Introduction Courtesy Preview This Introductory article that you are viewing is a courtesy preview of the full life Distinguishing Characteristics history account of this species. The remaining articles (Distribution, Habitat, Behavior, etc.), as well as the Multimedia Galleries and Reference sections of this Distribution account are subscriber-only content, and you will need a subscription in order to Systematics view the species account in its entirety. Click on the Subscribe tab for more Migration information. If you are already a current subscriber, you will need to sign in with your login Habitat information to access BNA normally. Food Habits Sounds Behavior Introduction Breeding The Roseate Tern is a pale, medium-sized, black- capped tern with a wide distribution in tropical Demography and Populations seas, but it is local and usually uncommon over most of its range. Its dashing flight with rapid wing- Conservation and beats, swooping dives, and rosy bloom in spring Management breeding plumage are pleasures encountered on Appearance many coasts and offshore islands worldwide. A. C. Measurements Bent (1921: 256) wrote of his first specimen: “I shall never forget the thrill of pleasure I Priorities for Future Research experienced when I held in my hand, for the first time a Roseate Tern and admired with deepest Juvenile Roseate Tern; NY State, Acknowledgments August reverence the delicate refinement of one of About the Author(s) nature’s loveliest productions.” This tern is a specialized plunge-diver, feeding on small, schooling marine fish. -

Common, Arctic - and Roseate Terns: an Identification Review

Common, Arctic - and Roseate Terns: an identification review R. A. Hume urner, in 1544, referred to 'a Larus' and called it 'stern', apparently the TBlack Tern Chlidonias niger. Willughby, in 1678, referred to the terns as 'the least sort of gull, having a forked tail'. Gesner (1516-1565) referred to three terns in the genus Larus as well as gulls, and in 1662 Sir Thomas Browne wrote of 'Lari, seamews and cobs' in Norfolk, including Larus cinereus, apparently the Common Tern Sterna hirundo, commonly called Sterne, but also of the "Hirundo marirui or sca-swallowe, a bird much larger than a Swallow Hirundo rustica, neat, white and fork-tailed. The confusion with gulls continued for many years; indeed, it still does. In the General Synopsis, 1781, Latham knew the Common Tern well enough to publish an accurate plumage description, but he did not recognise Arctic S. paradisaea, Roseate S. dougallii and Sandwich Terns S. sandvicensis. Briinnich, however, had described the Arctic Tern as a separate species in 1764, despite Henry Seebohm's later assertion that the distinction was not made until 1819. Montagu did not mention Arctic Tern in his 1802 Dictionary of British Birds, although he was good enough to distinguish difficult pairs such as Hen Circus cyaneus and Montagu's Harriers C. pygargus. Iinnaeus, in 1758, made no men tion of the Arctic Tern either, although it is likely that the bird he described under the name Sterna hirundo hirundo was actually a specimen of an Arctic, not a Common Tern. The identification of Common, Arctic and Roseate Terns in the field still presents a challenge.