The Roseate Tern Is a Medium-Sized, Colonial-Nesting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Ethnicity, and Place in a Changing America: a Perspective

Chapter 1 Race, Ethnicity, and Place in a Changing America: A Perspective JOHN W. FRAZIER PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN AMERICAN HUMAN GEOGRAPHY Culture, and the human geography it produces, persists over a long time period. However, culture changes slowly, as does the visible landscape it produces and the ethnic meanings imbued by the group that shapes it. That many examples of persistent and new cultural landscapes exist in the United States is not surpris- ing given the major technological, demographic, and economic changes in American society since World War II (WWII). America emerged from WWII as one of two superpowers, developed and embraced technology that took Americans to the moon, created an electronics revolution that greatly modified the ways that Americans work and live, and built a globally unique interstate highway system, new housing stock, millions of additional automobiles, and otherwise increased its production to meet the challenge of nearly doubling its population be- tween 1950 and 2000. The post-WWII baby boom and massive immigration fueled population growth and modified American society in important ways, creating different needs and growing aspirations. A larger Afri- can American middle class also emerged during this post-war period. Leadership in a growing global economy enabled unprecedented economic growth that supported these changes. Some less positive changes occurred during this period as America repositioned itself in global affairs, while experiencing great domestic and global economic, social and political challenges. America fought and lost a war in Vietnam, experienced an energy crisis, and suffered through double-digit inflation and severe economic recession, which contributed to a more conservative mood in Washington, D.C. -

Prey Delivered to Roseate and Common Tern Chicks; Composition and Temporal Variability Carl Safina, Richard H

J. Field Ornithol., 61(3):331-338 PREY DELIVERED TO ROSEATE AND COMMON TERN CHICKS; COMPOSITION AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY CARL SAFINA, RICHARD H. WAGNER1, DAVID A. WITTING 2, AND KELLYJ. SMITH2 National Audubon Society 306 South Bay Ave Islip, New York 11751 USA Abstract.--We observedprey deliveriesto Roseate(Sterna dougallii) and Common (S. hi- rundo)tern chicks.Roseate Terns were highly specializedand fed their chicksmostly sandeels (Ammodytesamericanus), whereas Common Terns delivered a diversity of prey. Species compositionof deliveredprey varied annually and weekly. Of four major prey species,the proportionof deliveriescontaining anchovies, juvenile bluefish, and herring varied with the time of morning, whereasthe proportionmade up of sandeelsremained generally constant. ENTREGA DE ALIMENTO A POLLUELOS DE STERNA DOUGALLH Y S. HIRUNDO: COMPOSICION Y VARIABILIDAD TEMPORAL Sinopsis.--Obscrvamosla cntregade alimentoa polluelosde Sternadougallii y S. hirundo. Los adultosdc S. dougalliialimcntaron a suspolluclos muy particularmentecon individuos dc Ammodytesamericanus, micntras quc la otra cspccicdc gaviotaalimcnt6 a suspichoncs con una gran divcrsidaddc prcsas.La composici6ndcl alimcntocntrcgado a los pichoncs, result6variable a travis de1cstudio. Dc las cuatrocspccics dc pcccsutilizadas principalmcntc comoalimcnto para lospichoncs, la proporci6ncntrcgada quc contcnlaanchoas, pcz azulado y arcncavari6 a travfisdc lashoras dc la mafiana,micntras quc la quc contcnlaA. americanus pcrmancci6gcncralmcntc constantc. Ever since Volterra (1931) -

Bridled Tern Breeding Record in the United States

SCIENCE areamore closely, and quickly locat- ed a downy Bridled Tern chick crouched under one of the rocks which was usedas a perchby the BRIDLEDTERN adult. We have accumulated addi- tionalrecords of nestingat thissite in subsequentyears. BREEDING BridledTerns breed throughout the Bahamas and the Greater and LesserAntilles, and occur commonly offshoreFlorida and regularlyoff RECORDIN THE other southeasternstates, but this is thefirst evidence of breedingreport- edfor NorthAmerica north of Quin- UNITEDSTATES tana Roo on the Yucatan Peninsula (Howell et al. i99o). In this note we describe the islet, the Roseate Tern colony,and the BridledTern nest byPyne Hoffman, site,and compare the nesting habitat of these terns to that used in the Ba- AlexanderSprunt IV, hamas. The FloridaKeys are flankedto PeterKalla, and Mark Robson the eastand south by a line of coral reefsparalleling the main keysat a distance of 6 to i2 kilometers. The best-developed(and some of the On themorning of July •5, •987, two Terns(Sterna anaethetus) flying low shallowest)reefs occur along the reef of us(Sprunt and Hoffman) visited a overthe colony.One of theseterns margin,adjacent to thedeep water of RoseateTern (Sterna dougallih colony sat for extendedperiods on coral the FloridaStraits. The tern colony on a small coral rubble islet on Peli- rocksin the northeasternpart of the occupiesan isletof approximately canShoal, south of BocaChica Key, isletand circled, calling softly when one-fourthhectare composed of coral MonroeCounty, Florida. During in- we approached.We returnedto the rubble and sand located on a shallow spectionwe observedfour Bridled island that afternoon to examine the sectionof the fringingreef called Bridled Tern on Pelican Shoal. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

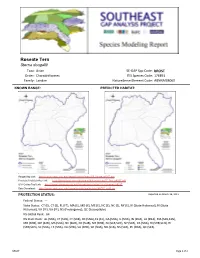

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Brost Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM08060

Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bROST Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM08060 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bROST.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bROST.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bROST Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bROST_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (E), CT (E), FL (FT), MA (E), MD (X), ME (E), NC (E), NC (E), NY (E), RI (State Historical), RI (State Historical), VA (LE), VA (LE), NS (Endangered), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G4 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), CT (S1B), CT (S1B), DE (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), IL (SNA), IN (SNA), LA (SNA), MA (S2B,S3N), MD (SHB), ME (S2B), MS (SNA), NC (SUB), NC (SUB), NH (SHB), NJ (S1B,S1N), NY (S1B), PA (SNA), RI (SHB,S1N), RI (SHB,S1N), SC (SNA), TX (SNA), VA (SHB), VA (SHB), WI (SNA), NB (S1B), NS (S1B), PE (SNA), QC (S1B) bROST Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 US Dept. -

1 the Intersection of Race and Ethnicity Among Hispanic Adolescents

The Intersection of Race and Ethnicity Among Hispanic Adolescents: Self-Identification and Friendship Choices Grace Kao and Elizabeth Vaquera Department of Sociology University of Pennsylvania 3718 Locust Walk Philadelphia, PA 19104-6299 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Draft: September 29, 2003 *Extended abstract submitted for consideration for presentation at the 2004 Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America. This research was supported by a grant from the NICHD (R01 HD38704-01A1) to the first author. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth/contract.html). 1 The Intersection of Race and Ethnicity Among Hispanic Adolescents: Self-Identification and Friendship Choices Abstract Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of youth in 7-12th grades, we examine how race and ethnicity overlap among Hispanic adolescents. We examine both self- identification and the choices of first-listed friends to evaluate the relative proximity between race and ethnic identifiers among Hispanics. Similar to previous work, we find a large contingent of Hispanics who choose Other Race, and smaller proportions who choose white or black as their racial group. -

A Sociological Literature Review Makenna Lindsay 2 November 2020

Blackness in the Spanish-speaking/Latin Caribbean: A Sociological Literature Review Makenna Lindsay 2 November 2020 This literature review will address the sociological research that exists as it relates to Blackness in the Spanish-speaking/Latin Caribbean. Personally, this topic was chosen largely because of my own Caribbean background and connection to the community, as well as my passions revolving around providing resources to and protecting the rights of Caribbean and Latin American populations. Sociologically, this topic is fascinating in that it addresses how the concept of “race” and its discriminatory effects function in a part of the Caribbean. The sociological research brings awareness to how Afro-Latinx communities are affected by “race,” especially with regard to the larger Latinx ethnic group. Studying Blackness in the region is significant to society because it considers the implications of the social construction of “race” in the Caribbean. Moreover, the sociological research that has been conducted with regard to this topic illustrates the marginalization of Afro-Latinx communities both historically and presently, and as well as how racism is ingrained in Latinx culture. Thus, this research concludes that historical and present occurrences of anti-Blackness pervade the culture of the Spanish-speaking/Latin Caribbean (including Haiti), isolating Afro-descendants in these countries from the rest of their populations. The first and one of the most important sections of this research examines the history of race in the Spanish-speaking/Latin Caribbean. Though this research predominantly concerns the racialized history on the island of Puerto Rico, there is a brief summary of Cuba’s racialized past as written by sociologist Nadine Fernandez. -

Species Assessment for Roseate Tern

Species Status Assessment Class: Birds Family: Laridae Scientific Name: Sterna dougallii Common Name: Roseate tern Species synopsis: The North Atlantic population of roseate tern breeds along the Atlantic Coast from the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence southward to New York; this population is federally endangered. A separate population breeds in the Caribbean; this population is federally threatened. As colonies in Virginia and New Jersey became extirpated, these two populations, both S. d. dougallii, have been moving farther from one another, since the 1930s. The North Atlantic population rebounded in the early 1900s following protection from hunting and peaked in the mid-1970s. Both the number of colonies and the number of breeding pairs have dropped since then. In New York, all colonies—historic and current—are on Long Island, with the vast majority of pairs (99% in 2010) nesting at Great Gull Island. Great Gull Island is the largest of only three primary colonies in the Northeast, resulting in an elevated risk of extirpation due to stochastic events. Nesting occurs in a variety of habitats including marshes, rocky islands, and open sand. I. Status a. Current and Legal Protected Status i. Federal ____Endangered______________________ Candidate? __N/A__ ii. New York ____Endangered; SGCN_________________________________________ b. Natural Heritage Program Rank i. Global ____G4_______________________________________________________________ ii. New York ____S1B_______________________ Tracked by NYNHP? __Yes___ 1 Other Rank: Partners in Flight – Priority IB The North Atlantic population is federally endangered while the Caribbean population is federally threatened. Status Discussion: Currently, the Northeast population hovers at about 4,300 pairs (1,697 in MA in 2001) (Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife 2005). -

Some Social Differences on the Basis of Race Among Puerto Ricans

Some Social Differences on the Basis of Race Among Puerto Ricans RESEARCH BRIEF Issued December 2016 By: Carlos Vargas-Ramos Centro RB2016-10 Puerto Ricans are a multiracial people. This is given by the fact that the Puerto Rican population is composed of people from different categories of socially differentiated and defined racial groups, and also because not an insig- nificant number of Puerto Rican individuals share ances- try derived from multiple racial groups. Yet, the analysis of social difference and inequities among Puerto Ricans on the basis of physical difference is largely avoided, and when it is conducted its findings are often neglected. This avoidance and neglect among Puerto Ricans tends of Management and Budget to establish racial categories to exist because the subject of race is generally fraught in the United States. Presently, and since the 1970s, these and uncomfortable, often sidestepped by allusions to col- categories have been listed broadly as American Indian or-blindness couched in racial democracy arguments or by and Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Native Hawaiian and oth- claiming that in an extensively miscegenated population er Pacific Islander, and White. The Office of Management not any one person or any one group of people could claim and Budget has also made a provision to include an open superiority over any other on the basis of physical attri- ended residual category to capture other racial categories butes.1 Moreover, social inequities on the basis of physical or designations that those listed may not (i.e., Some Other differences also tend to be avoided and neglected as a Race). -

Re-Imagining the Latino/A Race Ángel Oquendo University of Connecticut School of Law

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1995 Re-Imagining the Latino/a Race Ángel Oquendo University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Oquendo, Ángel, "Re-Imagining the Latino/a Race" (1995). Faculty Articles and Papers. 38. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/38 +(,121/,1( Citation: 12 Harv. Blackletter L. J. 93 1995 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 15 17:15:18 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=2153-1331 RE-IMAGINING THE LATINo/A RACE Angel R. Oquendo* En medio de esta brumada me ech6 a sofiar, a sofiar viejos suefios de mi raza, mitos de la tierra mia.1 I. INTRODUCTION Y bien, a fin de cuentas, Zqu6 es la Hispanidad? Ah, si yo la supiera ....Aunque no, mejor es que no la sepa, sino que la anhele, y la afiore, y la busque, y la presienta, porque es el modo de hacerla en mi.2 This Article condemns "racial" subcategories, such as "Black Hispan- ics" and "White Hispanics," which have been increasingly gaining cur- rency, and ultimately suggests that such categories should be vehemently rejected. -

Puerto Rican Ethnicity Challenged Through Racial Stratification

The Racial Paradox: Puerto Rican Ethnicity Challenged Through Racial Stratification By Gabriel Aquino Department of Sociology University At Albany, SUNY 1400 Washington Avenue Albany, NY, 12222 Aquino1 Introduction The Puerto Rican population in the United States has grown significantly since their initial migration in the 1950s. Currently in the United States, there are over 2.7 million Puerto Ricans, almost three-quarters of the population on the island of Puerto Rico (Rivera-Batiz- Santiago, 1994). Puerto Rican migrants to the United States encounter a culture very different from the Island’s culture. As Puerto Ricans develop as a community within the United States, they must confront many of these cultural differences. An extremely difficult challenge to the Puerto Rican community is the racial hierarchy that exists within the United States (Bonilla- Silva 1997; Omi and Winant 1994). This study is based on an earlier work conducted by Clara Rodriguez in 1991. Rodriguez, in her study, addresses one of the greatest problems faced by researchers who wish to study the effects of race on a multiracial group such as Puerto Ricans using U.S. Census data (Rivera-Batiz and Santiago, 1996; Rodriguez, 1996, 1994, 1991, 1991b; Gonzalez, 1993; Denton and Massey, 1989). Race on the United States Census questionnaire is self reported, this would require a clear understanding on what the choices mean. For immigrants from a multi-racial background, the racial categories in the US Census may have extremely different meanings than those understood by Census Researchers. Regardless of the possible confusions, the race category still may provide some indication of the level of integration of Puerto Ricans into the United States. -

STUDIES on the FAUNA of CURAÇAO and OTHER CARIBBEAN ISLANDS: No

STUDIES ON THE FAUNA OF CURAÇAO AND OTHER CARIBBEAN ISLANDS: No. 60. Life History of the Red-legged Thrush (Mimocichla plumbea ardosiacea) in Puerto Rico by Francis J. Rolle (University of Puerto Rico, Biology Department, Mayagiiez) page Introduction 1 Systeraatics 4 Sex determination 7 General activities 10 Voice 12 Food and foraging 15 Courtship and territory 18 Nests and nest building 21 and incubation 24 Eggs, egg laying, of and of 28 Hatching eggs development young Parental of the 31 care young 33 Comments on the breeding season Roosting and late-hour activities 34 Summary and conclusions 36 Bibliography 38 To the ornithologist the West Indies offer an assortment of field In that problems. an area where it is unlikely new species of birds will be and where of discovered, the life histories only a handful of birds are known, concentrated study of individual life histories becomes of prime importance. the third formal life of This paper represents history study a resident Puerto bird and second of Rican the a passeriform. 2 BIAGGI’S work the Rican of (1955) on Puerto race the Bananaquit the (Coereba flaveola portoricensis) was first life history done on the island with any degree of thoroughness. More recently RODRÍGUEZ- VIDAL (1959) made a three-year study of the Puerto Rican Parrot (Amazona vittata vittata), which has brought to light interesting informationon its previously unknown breeding habits. SPAULDING (1937) wrote three short papers in which she set down her observa- tions on the nesting habits of three native birds. The works in mentioned above plus a few scattered notes found the literature on nesting, distribution, and eggs make up the largest part of the published information concerning the Puerto Rican avifauna.