Tracking Offshore Occurrence of Common Terns, Endangered Roseate Terns, and Threatened Piping Plovers with VHF Arrays Appendices A-K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prey Delivered to Roseate and Common Tern Chicks; Composition and Temporal Variability Carl Safina, Richard H

J. Field Ornithol., 61(3):331-338 PREY DELIVERED TO ROSEATE AND COMMON TERN CHICKS; COMPOSITION AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY CARL SAFINA, RICHARD H. WAGNER1, DAVID A. WITTING 2, AND KELLYJ. SMITH2 National Audubon Society 306 South Bay Ave Islip, New York 11751 USA Abstract.--We observedprey deliveriesto Roseate(Sterna dougallii) and Common (S. hi- rundo)tern chicks.Roseate Terns were highly specializedand fed their chicksmostly sandeels (Ammodytesamericanus), whereas Common Terns delivered a diversity of prey. Species compositionof deliveredprey varied annually and weekly. Of four major prey species,the proportionof deliveriescontaining anchovies, juvenile bluefish, and herring varied with the time of morning, whereasthe proportionmade up of sandeelsremained generally constant. ENTREGA DE ALIMENTO A POLLUELOS DE STERNA DOUGALLH Y S. HIRUNDO: COMPOSICION Y VARIABILIDAD TEMPORAL Sinopsis.--Obscrvamosla cntregade alimentoa polluelosde Sternadougallii y S. hirundo. Los adultosdc S. dougalliialimcntaron a suspolluclos muy particularmentecon individuos dc Ammodytesamericanus, micntras quc la otra cspccicdc gaviotaalimcnt6 a suspichoncs con una gran divcrsidaddc prcsas.La composici6ndcl alimcntocntrcgado a los pichoncs, result6variable a travis de1cstudio. Dc las cuatrocspccics dc pcccsutilizadas principalmcntc comoalimcnto para lospichoncs, la proporci6ncntrcgada quc contcnlaanchoas, pcz azulado y arcncavari6 a travfisdc lashoras dc la mafiana,micntras quc la quc contcnlaA. americanus pcrmancci6gcncralmcntc constantc. Ever since Volterra (1931) -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: the Importance of Artificial Sites

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: The Importance of Artificial Sites Jeremy J. Hatch Terns are familiar coastal birds in Massachusetts, nesting widely, but they are most numerous from Plymouth southwards. Their numbers have fluctuated over the years, and the history of the four principal species was compiled by Nisbet (1973 and in press). Two of these have nested in Boston Harbor: the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) and the Least Tern (S. albifrons). In the late nineteenth century, the numbers of all terns declined profoundly throughout the Northeast because of intensive shooting of adults for the millinery trade (Doughty 1975), reaching their nadir in the 1890s (Nisbet 1973). Subsequently, numbers rebounded and reached a peak in the 1930s, declined again to the mid-1970s, then increased into the 1990s under vigilant protection (Blodget and Livingston 1996). In contrast, the first terns to nest in Boston Harbor in the twentieth century were not reported until 1968, and there are no records from the 1930s, when the numbers peaked statewide. For much of their subsequent existence the Common Terns have depended upon a sequence of artificial sites. This unusual history is the subject of this article. For successful breeding, terns require both an abimdant food supply and nesting sites safe from predators. Islands in estuaries can be ideal in both respects, and it is likely that terns were numerous in Boston Harbor in early times. There is no direct evidence for — or against — this surmise, but one of the former islands now lying beneath Logan Airport was called Bird Island (Fig. 1) and, like others similarly named, may well have been the site of a tern colony in colonial times. -

Bridled Tern Breeding Record in the United States

SCIENCE areamore closely, and quickly locat- ed a downy Bridled Tern chick crouched under one of the rocks which was usedas a perchby the BRIDLEDTERN adult. We have accumulated addi- tionalrecords of nestingat thissite in subsequentyears. BREEDING BridledTerns breed throughout the Bahamas and the Greater and LesserAntilles, and occur commonly offshoreFlorida and regularlyoff RECORDIN THE other southeasternstates, but this is thefirst evidence of breedingreport- edfor NorthAmerica north of Quin- UNITEDSTATES tana Roo on the Yucatan Peninsula (Howell et al. i99o). In this note we describe the islet, the Roseate Tern colony,and the BridledTern nest byPyne Hoffman, site,and compare the nesting habitat of these terns to that used in the Ba- AlexanderSprunt IV, hamas. The FloridaKeys are flankedto PeterKalla, and Mark Robson the eastand south by a line of coral reefsparalleling the main keysat a distance of 6 to i2 kilometers. The best-developed(and some of the On themorning of July •5, •987, two Terns(Sterna anaethetus) flying low shallowest)reefs occur along the reef of us(Sprunt and Hoffman) visited a overthe colony.One of theseterns margin,adjacent to thedeep water of RoseateTern (Sterna dougallih colony sat for extendedperiods on coral the FloridaStraits. The tern colony on a small coral rubble islet on Peli- rocksin the northeasternpart of the occupiesan isletof approximately canShoal, south of BocaChica Key, isletand circled, calling softly when one-fourthhectare composed of coral MonroeCounty, Florida. During in- we approached.We returnedto the rubble and sand located on a shallow spectionwe observedfour Bridled island that afternoon to examine the sectionof the fringingreef called Bridled Tern on Pelican Shoal. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

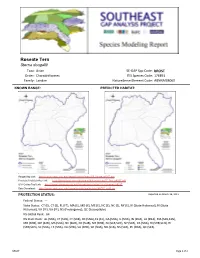

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Brost Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM08060

Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bROST Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM08060 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bROST.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bROST.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bROST Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bROST_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (E), CT (E), FL (FT), MA (E), MD (X), ME (E), NC (E), NC (E), NY (E), RI (State Historical), RI (State Historical), VA (LE), VA (LE), NS (Endangered), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G4 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), CT (S1B), CT (S1B), DE (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), IL (SNA), IN (SNA), LA (SNA), MA (S2B,S3N), MD (SHB), ME (S2B), MS (SNA), NC (SUB), NC (SUB), NH (SHB), NJ (S1B,S1N), NY (S1B), PA (SNA), RI (SHB,S1N), RI (SHB,S1N), SC (SNA), TX (SNA), VA (SHB), VA (SHB), WI (SNA), NB (S1B), NS (S1B), PE (SNA), QC (S1B) bROST Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 US Dept. -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

1 Common Tern Survey and Reproductive Monitoring Reporting

Common Tern Survey and Reproductive Monitoring Reporting Office: Seney NWR (US Coast Guard Station, St. Ignace) Species: Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) JUSTIFICATION AND OBJECTIVES The Common Tern is a circumpolar colonial waterbird that in North America breeds in coastal areas of the northern United States and Canada. In the Midwest, the Common Tern is listed as a Conservation Priority due to habitat loss (and competition for habitat), predation, and pollution. Within the Great Lakes region, competition with Ring-billed Gulls for breeding habitat is a major influence on Common Tern numbers. Habitat loss is also a result of increased human development along shorelines and on islands. In addition, human disturbance (such as loud noises) near a colony can cause adults to abandon their nests and the colony. Predators are also a threat to Common Terns because they prey upon both eggs and young. Mammalian predators include skunk, coyote, Norway rat, domesticated cat, fox, and mink. Other common predators include owls and gulls. Finally, aquatic pollutants pose a threat to Common Terns as they are mainly piscivorous and are especially vulnerable to pollutants which have an adverse effect on eggs and young. Starting in 2001, Seney NWR began to work cooperatively with the US Coast Guard at the St. Ignace moorings to protect one of the largest Common Tern colonies in Michigan, with a formal agreement signed between the parties in 2010. According to this agreement: “……between May 1 and September 30 (very conservative) no activity should be undertaken in the fenced portion of the pier. In addition, no buoys should be moved in or out of this area unless necessary for the safety of human life. -

Species Assessment for Roseate Tern

Species Status Assessment Class: Birds Family: Laridae Scientific Name: Sterna dougallii Common Name: Roseate tern Species synopsis: The North Atlantic population of roseate tern breeds along the Atlantic Coast from the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence southward to New York; this population is federally endangered. A separate population breeds in the Caribbean; this population is federally threatened. As colonies in Virginia and New Jersey became extirpated, these two populations, both S. d. dougallii, have been moving farther from one another, since the 1930s. The North Atlantic population rebounded in the early 1900s following protection from hunting and peaked in the mid-1970s. Both the number of colonies and the number of breeding pairs have dropped since then. In New York, all colonies—historic and current—are on Long Island, with the vast majority of pairs (99% in 2010) nesting at Great Gull Island. Great Gull Island is the largest of only three primary colonies in the Northeast, resulting in an elevated risk of extirpation due to stochastic events. Nesting occurs in a variety of habitats including marshes, rocky islands, and open sand. I. Status a. Current and Legal Protected Status i. Federal ____Endangered______________________ Candidate? __N/A__ ii. New York ____Endangered; SGCN_________________________________________ b. Natural Heritage Program Rank i. Global ____G4_______________________________________________________________ ii. New York ____S1B_______________________ Tracked by NYNHP? __Yes___ 1 Other Rank: Partners in Flight – Priority IB The North Atlantic population is federally endangered while the Caribbean population is federally threatened. Status Discussion: Currently, the Northeast population hovers at about 4,300 pairs (1,697 in MA in 2001) (Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife 2005). -

STATUS ASSESSMENT and CONSERVATION RECOMMENDATIONS for the COMMON TERN (Sterna Hirundo) in the GREAT LAKES REGION

STATUS ASSESSMENT AND CONSERVATION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE COMMON TERN (Sterna hirundo) IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION Francesca J. Cuthbert Linda R. Wires Kristina Timmerman University of Minnesota Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Biology 1980 Folwell Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 USA September 2003 For additional copies, contact: Nongame Bird Coordinator U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Federal Bldg., 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111-4056 Recommended Citation: Cuthbert, F.J., Wires, L.R. and K. Timmerman. 2003. Status Assessment and Conservation Recommendations for the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) in the Great Lakes Region. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Ft. Snelling, MN. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………..iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………….….1 BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………..2 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….…………………2 TAXONOMY…………………………………………………………………………….3 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION……………………………………………………………3 RANGE…………………………………………………………………………………...4 BAND RECOVERY DATA AND POPULATION BOUNDARIES……………….…5 HABITAT………………………………………………………………………………...6 Breeding Season Habitat Requirements…………………………………………...6 Post-Breeding Staging Habitat Requirements……………………………………..8 Winter Habitat Requirements……………………………………………………...8 BIOLOGY………………………………………………………………………..………8 Migration and Wintering Grounds………………………………………………...8 Reproduction………………………………………………………………………9 Diet and Foraging Ecology………………………………………………………10 Mortality and Longevity…………………………………………………………11 POPULATION SIZE AND TRENDS………………...………………………..12