The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Record of a California Gull for North Carolina

General Field Notes LYNN MOSELEY EIS M. OSYE rth Crln Edtr Sth Crln Edtr prtnt f l prtnt f l Glfrd Cll h Ctdl Grnbr, C 240 Chrltn, SC 240 OICE Publication of any unusual sightings of birds in the Field Notes or Briefs for the Files does not imply that these reports have been accepted into the official Checklist of Birds records for either North or South Carolina. Decisions regarding the official Checklists are made by the respective State Records Committees and will be reported upon periodically in THE CHAT. rt rd f Clfrn Gll fr rth Crln Stephen J. Dinsmore John O. Fussell Jeremy Nance 2600 Glen Burnie 1412 Shepard Street 3259 N 1st Avenue Raleigh, NC 27607 Morehead City, NC 28557 Tucson, AZ 85719 At approximately 1400 h on 29 January 1993, we observed an adult California Gull (Larus californicus) at the Carteret County landfill, located southwest of Newport, North Carolina. We were birding the northwest corner of the landfill when Fussell called our attention to a slightly darker-mantled gull resting with hundreds of other gulls, mostly Herring Gulls (L. argentatus). We immediately recognized the bird as an adult California Gull. We were able to observe and photograph the bird for the nest half hour at distances of 75-100 m. At 1430 the bird suddenly flew south over the dump and we were not able to relocated it over the next 2 hours. Sprn 6 The following is a detailed description of the bird, much of it written immediately after the sighting. The bird was slightly smaller and slimmer than the numerous Herring Gulls surrounding it. -

(369) the Glaucous Gull in Winter

(369) THE GLAUCOUS GULL IN WINTER BY G. T. KAY. (Plates 40-53). SINCE the winter of 1941-42 the Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus) has become a comparatively numerous winter-visitor to the Shet land Islands. At a refuse dump on the outskirts of Lerwick where it had been rare to see more than half a dozen of these birds together, it is now a common occurrence to see thirty or forty and occasion ally as many as a hundred. During the winter of 1945-46, the writer, with others interested in the project, arranged for an attempt to be made to photograph particularly Glaucous Gulls and possibly Iceland Gulls (Larus glaucoides) in the vicinity of the dump. The proposal was to use still and cine cameras from hides. It was hoped that a series of photographs might be secured which would do something towards clearing up the difficulties of dis tinguishing between these two species in the field, which have proved to be in some respects greater than used to be supposed. We were fortunate as regards the Glaucous Gull. A series of photographs and 300ft. of cine film were taken of this arctic visitor at most stages of plumage from the bird in its first winter plumage to that of the fully adult. Further photographs were added during the winter of 1946-47. Unfortunately the only Iceland Gull seen during these two winters was a dead specimen ; an immature bird in its first winter which had been captured on a fishing boat off the east side of Shetland on January 16th, 1947. -

Nesting Populations of California and Ring-Billed Gulls in California

WESTERN BIR Volume 31, Number 3, 2000 NESTING POPULATIONS OF CLwO AND RING-BI--F-r GULLS IN CALIFORNIA: RECENT SURVEYS AND HISTORICAL STATUS W. DAVID SHUFORD, Point Reyes Bird Observatory(PRBO), 4990 Shoreline Highway, StinsonBeach, California94970 THOMAS P. RYAN, San FranciscoBay Bird Observatory(SFBBO), P.O. Box 247, 1290 Hope Street,Alviso, California 95002 ABSTRACT: Statewidesurveys from 1994 to 1997 revealed33,125 to 39,678 breedingpairs of CaliforniaGulls and at least9611 to 12,660 pairsof Ring-billed Gullsin California.Gulls nested at 12 inland sitesand in San FranciscoBay. The Mono Lake colonywas by far the largestof the CaliforniaGull, holding 70% to 80% of the statepopulation, followed by SanFrancisco Bay with 11% to 14%. ButteValley WildlifeArea, Clear Lake NationalWildlife Refuge, and Honey Lake WildlifeArea were the only othersites that heldover 1000 pairsof CaliforniaGulls. In mostyears, Butte Valley, Clear Lake, Big Sage Reservoir,and Honey Lake togetherheld over 98% of the state'sbreeding Ring-billed Gulls; Goose Lake held9% in 1997. Muchof the historicalrecord of gullcolonies consists of estimatestoo roughfor assessmentof populationtrends. Nevertheless, California Gulls, at least,have increased substantially in recentdecades, driven largely by trendsat Mono Lake and San FranciscoBay (first colonizedin 1980). Irregularoccupancy of some locationsreflects the changing suitabilityof nestingsites with fluctuatingwater levels.In 1994, low water at six sites allowedcoyotes access to nestingcolonies, and resultingpredation appeared to reducenesting success greatly at threesites. Nesting islands secure from predators and humandisturbance are nestinggulls' greatest need. Conover(1983) compileddata suggestingthat breedingpopulations of Ring-billed(Larus delawarensis)and California(Larus californicus)gulls haveincreased greafiy in the Westin recentdecades. Detailed assessments of populationstatus and trends of these speciesin individualwestern states, however,have been publishedonly for Washington(Conover et al. -

Laughing Gulls Breed Primarily Along the Pacific Coast of Mexico and the Atlantic and Caribbean Coasts from S

LAUGHING GULL Leucophaeus atricilla non-breeding visitor, regular winterer L.a. megalopterus Laughing Gulls breed primarily along the Pacific coast of Mexico and the Atlantic and Caribbean coasts from s. Canada to Venezuela, and they winter S to Peru and the Amazon delta (AOU 1998, Howell and Dunn 2007). It and Franklin's Gull were placed along with other gulls in the genus Larus until split by the AOU (2008). Vagrant Laughing Gulls have been reported in Europe (Cramp and Simmons 1983) and widely in the Pacific, from Clipperton I to Wake Atoll (Rauzon et al. 2008), Johnston Atoll (records of at least 14 individuals, 1964-2003), Palmyra, Baker, Kiribati, Pheonix, Marshall, Pitcairn, Gambier, and Samoan Is, as well as Australia/New Zealand (King 1967; Clapp and Sibley 1967; Sibley and McFarlane 1968; Pratt et al. 1987, 2010; Garrett 1987; Wragg 1994; Higgins and Davies 1996; Vanderwerf et al. 2004; Hayes et al. 2015; E 50:13 [identified as Franklin's Gull], 58:50). Another interesting record is of one photographed attending an observer rowing solo between San Francisco and Australia at 6.5° N, 155° W, about 1400 km S of Hawai'i I, 1-2 Nov 2007. They have been recorded almost annually as winter visitors to the Hawaiian Islands since the mid-1970s, numbers increasing from the NW to the SE, as would be expected of this N American species. The great majority of records involve first-year birds, and, despite the many records in the S Pacific, there is no evidence for a transient population through the Hawaiian Islands, or of individuals returning for consecutive winters after departing in spring. -

Fuscus and Larus Affixis

542 Dwight, Larus fuscus and Larus affinis. [q^ THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE GULLS KNOWN AS LARUS FUSCUS AND LARUS AFFIXIS. BY JONATHAN DWIGHT, M. D. Plates XX and XXI. \n approaching many of the problems in modern systemic ornithology, one is confronted with the necessity of steering a middle course between the Scylla of imperfect knowledge on the one hand and the Charybdis of nomenclature on the other. Either may bring us to shipwreck; but mindful of those who have pre- ceded me in writing about the Lesser Black-backed Gull (Larus fuscus), and the Siberian Gull (Larus affinis), I venture with some hesitancy to take up the tangled question of the relationship of these birds and make another endeavor to fix the proper names upon them. Larus fuscus, an abundant European species, was described in 1758 by Linnaeus, and has never been taken on the American side of the Atlantic. L. affinis, however, has stood as a North American ' species in the A. O. U. Check-Lists ' on the strength of a single specimen, the type taken in southern Greenland and described by Reinhardt in 1853 (Videnskab-Meddel, p. 78). Until 1912 these two gulls were recognized as two full species, and then Lowe (Brit. Birds, VI, no. 1, June 1, 1912, pp. 2-7, pi. 1) started the ball rolling by restricting the name fuscus to Scandi- navian birds and describing the paler bird of the British Isles subspecifically as brittanicus. A few months later Iredale (Brit. Birds, VI, no. 12, May 1, 1913, pp. 360-364, with pi.), borrowing the type of affinis from the Copenhagen Museum, where it had rested for half a century, and comparing it with British specimens, found it to be identical with them; but not content with synonymyzing brittanicus with affin is, he reached the conclusion that the Siberian bird was larger and therefore required a new name — antelius. -

First Confirmed Record of Belcher's Gull Larus Belcheri for Colombia with Notes on the Status of Other Gull Species

First confirmed record of Belcher's Gull Larus belcheri for Colombia with notes on the status of other gull species Primer registro confirmado de la Gaviota Peruana Larus belcheri para Colombia con notas sobre el estado de otras especies de gaviotas Trevor Ellery1 & José Ferney Salgado2 1 Independent. Email: [email protected] 2 Corporación para el Fomento del Aviturismo en Colombia. Abstract We present photographic records of a Belcher's Gull Larus belcheri from the Colombian Caribbean region. These are the first confirmed records of this species in the country. Keywords: new record, range extension, gull, identification. Resumen Presentamos registros fotograficos de un individuo de la Gaviota Peruana Larus belcheri en la region del Caribe de Colombia. Estos son los primeros registros confirmados para el país. Palabras clave: Nuevo registro, extensión de distribución, gaviota, identificación. Introduction the Pacific Ocean coasts of southern South America, and Belcher's Gull or Band-tailed Gull Larus belcheri has long Olrog's Gull L. atlanticus of southern Brazil, Uruguay and been considered a possible or probable species for Argentina (Howell & Dunn 2007, Remsen et al. 2018). Colombia, with observations nearby from Panama (Hilty & Brown 1986). It was first listed for Colombia by Salaman A good rule of thumb for gulls in Colombia is that if it's not et al. (2001) without any justification or notes, perhaps on a Laughing Gull Leucophaeus atricilla, then it's interesting. the presumption that the species could never logically have A second good rule of thumb for Colombian gulls is that if reached the Panamanian observation locality from its it's not a Laughing Gull, you are probably watching it at Los southern breeding grounds without passing through the Camarones or Santuario de Fauna y Flora Los Flamencos, country. -

Black-Headed Gull Chroicocephalus Ridibundus

Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus Folk Name: Common Black-headed Gull Status: Migrant Abundance: Accidental Habitat: Open water of lakes and rivers The Black-headed Gull is a Eurasian gull that occasionally shows up in the Carolinas between early August and the end of April. It was first confirmed in North Carolina at Fort Macon on August 10, 1967, and was first confirmed in South Carolina at Huntington Beach State Park on October 29, 1970. It used to be called the “Common Black-headed Gull.” It is almost always seen with Ring- billed Gulls, although one Carolina ornithologist noted “that association may relate more to the abundance of Ring-billed Gulls in winter than any biological affinity it was relocated, several groups of excited observers were between the two.” The Black-headed Gull is a rare but allowed access into the wastewater treatment plant to see regular visitor along the coast of the Carolinas. There this special bird. are only four records of this gull inland in the Carolina Remarkably, a second Black-headed Gull, an adult Piedmont. The first two records were of birds found at bird, was sighted in Mecklenburg County on Mountain Jordan Lake on January 16, 2005, and at Falls Lake on Island Lake on December 16, 2012. Dennis Kent, John December 9, 2010. The latest records are of two sightings Scavetto, and Bill Rowse were scouring the lake during here in the Central Carolinas. the Southern Lake Norman Christmas Bird Count when At times, the discovery of a rare bird is often an they found this bird. -

22 First Certain Record of California Gull (Larus

22 NOTES Florida Field Naturalist 28(1):22-24, 2000. FIRST CERTAIN RECORD OF CALIFORNIA GULL (LARUS CALIFORNICUS) IN FLORIDA DOUGLAS B. MCNAIR Tall Timbers Research Station, 13093 Henry Beadel Drive, Tallahassee, Florida 32312-0918 The status of California Gull (Larus californicus) in Florida, prior to this record, is unresolved. Robertson and Woolfenden (1992) placed California Gull on their unverified list, while Stevenson and Anderson (1994) placed it on their accredited list (see Wool- fenden et al. 1996). I follow the criteria of Robertson and Woolfenden (1992). Gulls in their third winter were photographed in Pinellas County in 1978 and 1979; species identification was not considered certain although the birds probably were California Gulls (Robertson and Woolfenden 1992, Stevenson and Anderson 1994). Following the ambiguous photographs, six sight observations of California Gulls have been reported. The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee (FOSRC) rejected two reports; two undetailed reports never reviewed by the FOSRC lack documentation (Baker 1991a, b; Stevenson and Anderson 1994); and two detailed reports (a bird seen in late October 1982 [Stevenson and Anderson 1994] and an adult in February 1983 [Powell 1986, FOSRC]) are valid, although formal documentation is lacking for each. Both valid reports occurred on the peninsula, one on Gulf coast (Pinellas County), the other on the Atlantic coast (Brevard County). I discovered a first-winter California Gull at Apalachicola, Franklin County, on 26 Sep- tember 1998, when Hurricane Georges was more than 300 km offshore. Sustained winds at Apalachicola were about 50 km. The bird was associated with a mixed flock of gulls, terns, and skimmers resting on a partially flooded vacant lot at the tip of a small penin- sula at the mouth of the Apalachicola River. -

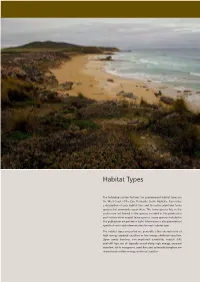

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

The Primary Moult in Four Gull Species Near Amsterdam J. Walters

THE PRIMARY MOULT IN FOUR GULL SPECIES NEAR AMSTERDAM J. WALTERS Received IS April 1978 CONTENTS I. Introduction and study area ... 32 2. Methods and materials ..... 33 2.1. Moult observations on dead gulls 33 2.2. Collection of newly shed primaries 34 2.3. Identification of primaries collected 34 2.4. "Average" primary per date of collection 36 2.5. Average date of shedding per primary 36 2.6. Sampling ......... 37 3. Results ............ 37 3.1. Black-headed Gull, adult .. 37 3.2. Black-headed Gull, sub-adult 38 3.3. Common Gull, adult .. 39 3.4. Common Gull, sub-adult .. 40 3.5. Herring Gull, adult 40 3.6. Herring Gull, sub-adult ... 42 3.7. Great Black-backed Gull, adult 42 3.8. Primary moult and reproduction 42 4. Discussion 43 5. Acknowledgements 46 6. Summary .. 46 7. References . 46 8. Samenvatting ... 46 1. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY AREA This paper deals with the primary moult in Black-headed Gull Larus ridibundus, Common Gull Larus canus, Herring Gull Larus argentatus and Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus in areas near Amsterdam. Though a few studies on the moult of gulls already exist for the NW-European area, e.g. Stresemann & Stresemann (1966), Stresemann (1971), Barth (1975), Harris (1971), Ingolfsson (1970) and Verbeek (1977), such a study has not been published for a Dutch area and not for four Larus species at the same time and in the same restricted region. Moreover, for the three first mentioned species new information could be obtained on the timing of moult in relation to the incubation period. -

Franklin's Gull Larus Pipixcan at Tanggu, Tianjin: First Record for China

Forktail 21 (2005) SHORT NOTES 171 CONSERVATION and Dilip Roy for dedicated assistance in the field during the study. At Buxa Tiger Reserve, Jerdon’s and Black Bazas are not directly targeted for hunting or persecution. Both REFERENCES species are listed on Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972. Ali, S. and Ripley, S. D. (1987) Compact handbook of the birds of India A wide range of pesticides are used in the tea and Pakistan. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. gardens surrounding the reserve where bazas feed, and Baker, E. C. S. (1935) The nidification of the birds of the Indian Empire. London: Taylor and Francis. this may have detrimental consequences for them. Brown, L. H. (1955) Supplementary notes on the biology of the Monitoring pesticide use and residues in birds would large birds of prey of Enbu District, Kenya Colony. Ibis 97: be desirable. Illegal woodcutting was noted throughout 38–64, 183–221. the reserve. Selective removal of mature tall trees may Ferguson-Lees, J. and Christie, D. A. (2001) Raptors of the world. reduce the availability of nest sites for bazas. London: A. & C. Black. Prevention of such activities is needed immediately. Grossman, M. L., Grossman, S. and Hamlet, J. (1965) Birds of prey of the world. London: Cassell & Co. Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C. and Inskipp, T. (1998) Birds of the Indian subcontinent. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. and Sargatal, J., eds. (1994) Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. 2. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. We thank the U. S. -

Foraging Ecology of Great Black-Backed and Herring Gulls on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy by Rolanda J Steenweg Submitted In

Foraging Ecology of Great Black-backed and Herring Gulls on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy By Rolanda J Steenweg Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honours Bachelor of Science in Environmental Science at: Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2010 Supervisors: Dr. Robert Ronconi Dr. Marty Leonard ENVS 4902 Professor: Dr. Daniel Rainham TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 7 2.1 General biology and reproduction 7 2.2 Composition of adult and chick gull diets - changes over the breeding season8 2.3 General similarities and differences between gull species 9 2.4Predation on Common Eider Ducklings 10 2.5Techniques 10 3. MATERIALS AND METHODS 13 3.1 Study site and species 13 3.2 Lab Methods 16 3.3 Data Analysis 17 4. RESULTS 18 4.1 Pellet and regurgitate samples 19 4.2 Stable isotope analysis 21 4.3 Estimates of diet 25 5. DISCUSSION 26 5.1 Main components of diet 26 5.2 Differences between species and age classes 28 5.3 Variability between breeding stages 30 5.4 Seasonal trends in diet 32 5.5 Discrepancy between plasma and red blood cell stable isotope signatures 32 6. CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 33 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 35 REFERENCES 36 2 ABSTRACT I studied the foraging ecology of the generalist predators Great Black-backed (Larusmarinus) and Herring (Larusargentatus) Gulls on Kent Island, in the Bay of Fundy. To study diet, I collected pellets casted in and around nests supplemented with tissue samples (red blood cells, plasma, head feathers and primary feathers) obtained from chicks and adults for stable isotope analysis.