Mytern Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

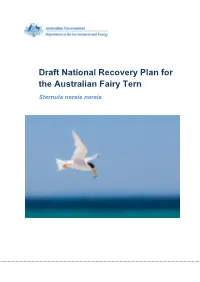

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

The Primary Moult in Four Gull Species Near Amsterdam J. Walters

THE PRIMARY MOULT IN FOUR GULL SPECIES NEAR AMSTERDAM J. WALTERS Received IS April 1978 CONTENTS I. Introduction and study area ... 32 2. Methods and materials ..... 33 2.1. Moult observations on dead gulls 33 2.2. Collection of newly shed primaries 34 2.3. Identification of primaries collected 34 2.4. "Average" primary per date of collection 36 2.5. Average date of shedding per primary 36 2.6. Sampling ......... 37 3. Results ............ 37 3.1. Black-headed Gull, adult .. 37 3.2. Black-headed Gull, sub-adult 38 3.3. Common Gull, adult .. 39 3.4. Common Gull, sub-adult .. 40 3.5. Herring Gull, adult 40 3.6. Herring Gull, sub-adult ... 42 3.7. Great Black-backed Gull, adult 42 3.8. Primary moult and reproduction 42 4. Discussion 43 5. Acknowledgements 46 6. Summary .. 46 7. References . 46 8. Samenvatting ... 46 1. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY AREA This paper deals with the primary moult in Black-headed Gull Larus ridibundus, Common Gull Larus canus, Herring Gull Larus argentatus and Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus in areas near Amsterdam. Though a few studies on the moult of gulls already exist for the NW-European area, e.g. Stresemann & Stresemann (1966), Stresemann (1971), Barth (1975), Harris (1971), Ingolfsson (1970) and Verbeek (1977), such a study has not been published for a Dutch area and not for four Larus species at the same time and in the same restricted region. Moreover, for the three first mentioned species new information could be obtained on the timing of moult in relation to the incubation period. -

Environmental Contaminants in Arctic Tern Eggs from Petit Manan Island

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine May 2001 Mission Statement U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service “Our mission is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance the nation’s fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.” Suggested citation: Mierzykowski S.E., J.L. Megyesi and K.C. Carr. 2001. Environmental contaminants in Arctic tern eggs from Petit Manan Island. USFWS. Spec. Proj. Rep. FY96-MEFO-6-EC. Maine Field Office. Old Town, ME. 40 pp. Report reformatted 1/2009 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine Prepared by: Steven E. Mierzykowski1, Jennifer L. Megyesi2, and Kenneth C. Carr3 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Maine Field Office 1033 South Main Street Old Town, Maine 04468 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Main Street, P.O. Box 279 Milbridge, Maine 04658 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service New England Field Office 70 Commercial Street, Suite 300 Concord, New Hampshire 03301-5087 May 2001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Petit Manan Island is a 3.5-hectare (~ 9 acre) island that lies approximately 4-kilometers (2.5-miles) from the coastline of Petit Manan Point, Steuben, Washington County, Maine. It is one of nearly 40 coastal islands within the Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge. -

Fairy Tern (Sternula Nereis) Conservation in South- Western Australia

FAIRY TERN (STERNULA NEREIS) CONSERVATION IN SOUTH- WESTERN AUSTRALIA A guide prepared by J.N. Dunlop for the Conservation Council of Western Australia. Supported by funding from the Western Australian Government’s State Natural Resource Management Program AckNowleDgemeNts The field research underpinning this guide was supported by the grant of various authorities and in-kind contributions from the Department of Parks & Wildlife (WA) and the Department of Fisheries (WA). The Northern Agricultural Catchment Council (NACC) supported some of the work in the Houtman Abrolhos. Many citizen-scientists have assisted along the way but particular thanks are due to the long-term contribution of Sandy McNeil. Peter Mortimer Unique Earth and Tegan Douglas kindly granted permission for the use of their photographs. The production of the guide to ‘Fairy Tern Conservation in south-western Australia’ was made possible by a grant from WA State NRM Office. This document may be cited as ‘Dunlop, J.N. (2015). Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis) conservation in south-western Australia. Conservation Council (WA), Perth.’ Design & layout: Donna Chapman, Red Cloud Design Published by the Conservation Council of Western Australia Inc. City West Lotteries House, 2 Delhi Street, West Perth, WA 6005 Tel: (08) 9420 7266 Email: [email protected] www.ccwa.org.au © Conservation Council of Western Australia Inc. 2015 Date of publication: September 2015 Tern photos on the cover and the image on this page are by Peter Mortimer Unique Earth. Contents 1. The Problem with Small Terns (Genus: Sternula) 2 2. The Distribution and Conservation Status of Australian Fairy Tern populations 3 3. -

LOCAL ACTION PLAN for the COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula

LOCAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula nereis SOUTH AUSTRALIA David Baker-Gabb and Clare Manning Cover Page: Adult Fairy Tern, Coorong National Park. P. Gower 2011 © Local Action Plan for the Coorong Fairy Tern Sternula nereis South Australia David Baker-Gabb1 and Clare Manning2 1 Elanus Pty Ltd, PO BOX 131, St. Andrews VICTORIA 3761, Australia 2 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, PO BOC 314, Goolwa, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5214, Australia Final Local Action Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Baker-Gabb, D., and Manning, C., (2011) Local Action Plan the Coorong fairy tern Sternula nereis, South Australia. Final Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Acknowledgements The authors express thanks to the people who shared their ideas and gave their time and comments. We are particularly grateful to Associate Professor David Paton of the University of Adelaide and to the following staff from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources; Daniel Rogers, Peter Copley, Erin Sautter, Kerri-Ann Bartley, Arkellah Hall, Ben Taylor, Glynn Ricketts and Hafiz Stewart for the care with which they reviewed the original draft. Through the assistance of Lachlan Sutherland, we thank members of the Ngarrindjeri Nation who shared ideas, experiences and observations. Community volunteer wardens have contributed significant time and support in the monitoring of the Coorong fairy tern and the data collected has informed the development of the Plan. The authors gratefully appreciate that your time volunteering must be valued but one can never put a value on that time. Executive Summary The Local Action Plan for the Coorong fairy tern (the Plan) has been written in a way that, with a minimum of revision, may inform a National and State fairy tern Recovery Plan. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Field Identification of West Palearctic Gulls P

British Birds VOLUME 71 NUMBER 4 APRIL 1978 Field identification of west Palearctic gulls P. J. Grant The west Palearctic list includes 23 species of gulls: more than half the world total. Field guides—because of their concise format—provide inad equate coverage of identification and ageing, which has probably fostered the indifference felt by many bird watchers towards gulls. This five- part series aims to change that attitude nterest in identifying gulls is growing, as part of the recent general I improvement in identification standards, but doubtless also stimulated by the addition to the British and Irish list of no less than three Nearctic species in little over a decade (Laughing Gull Larus atricilla in 1966, Franklin's Gull L. pipixcan in 1970 and Ring-billed Gull L. delaivarensis in 1973). The realisation is slowly dawning that regular checking through flocks of gulls can be worthwhile. Just as important as identification is the ability to recognise the age of individual immatures. This is obviously necessary in studies of popula tion, distribution and migration, but is also a challenge in its own right to the serious bird-identifier. Indeed, identification and ageing go hand- in-hand, for it is only by practising his recognition skills on the common species—of all ages—that an observer will acquire the degree of familiarity necessary for the confident identification of the occasional rarity. The enormous debt owed to D.J. Dwight's The Gulls of the World (1925) is readily acknowledged. That work, however, has long been out of print and its format was designed for the museum and taxonomic worker; the present series of papers will provide a reference more suited to field observers. -

Have We All Missed the Point About Seagulls? Written by Joe Reynolds, Save Coastal Wildlife, Published: 20 February 2020

Have We All Missed the Point About Seagulls? Written by Joe Reynolds, Save Coastal Wildlife, Published: 20 February 2020 Along the picturesque Jersey Shore, a remarkable drama plays out almost every time someone visits a beach. No matter the season, from summer to spring, people will encounter gulls, erroneously known as seagulls. For me, I have a soft spot in my heart for these largely grey-and-white birds. They can be awe-inspiring sea creatures when soaring over the open ocean and dropping down out for the sapphire sky to catch a slimy fish or crusty crab. The sight of them brings to mind a sense of the long soft sand shorelines and sweeping winds and waves over a sun-and-shelled filled beach. Gulls are extraordinary birds. They are able to fly long distances and glide over the open ocean for hours in search of food. Gulls can fly as fast as 28 mph. They can even drink salty ocean water when thirsty. The birds have evolved to have a special pair of glands right above their eyes to flush the salt from their body through openings in their bill. This enables a gull to spend several days foraging for food atop salty ocean waters without needing to return to land just to get a drink of freshwater. James Gorman in 2019 wrote an article in The New York Times entitled: “In Defense of Sea Gulls: They’re Smart, and They Co-Parent, 50/50 All the Way.” He interviewed ornithologist Christopher Elphick from the University of Connecticut who also has a soft spot for gulls.