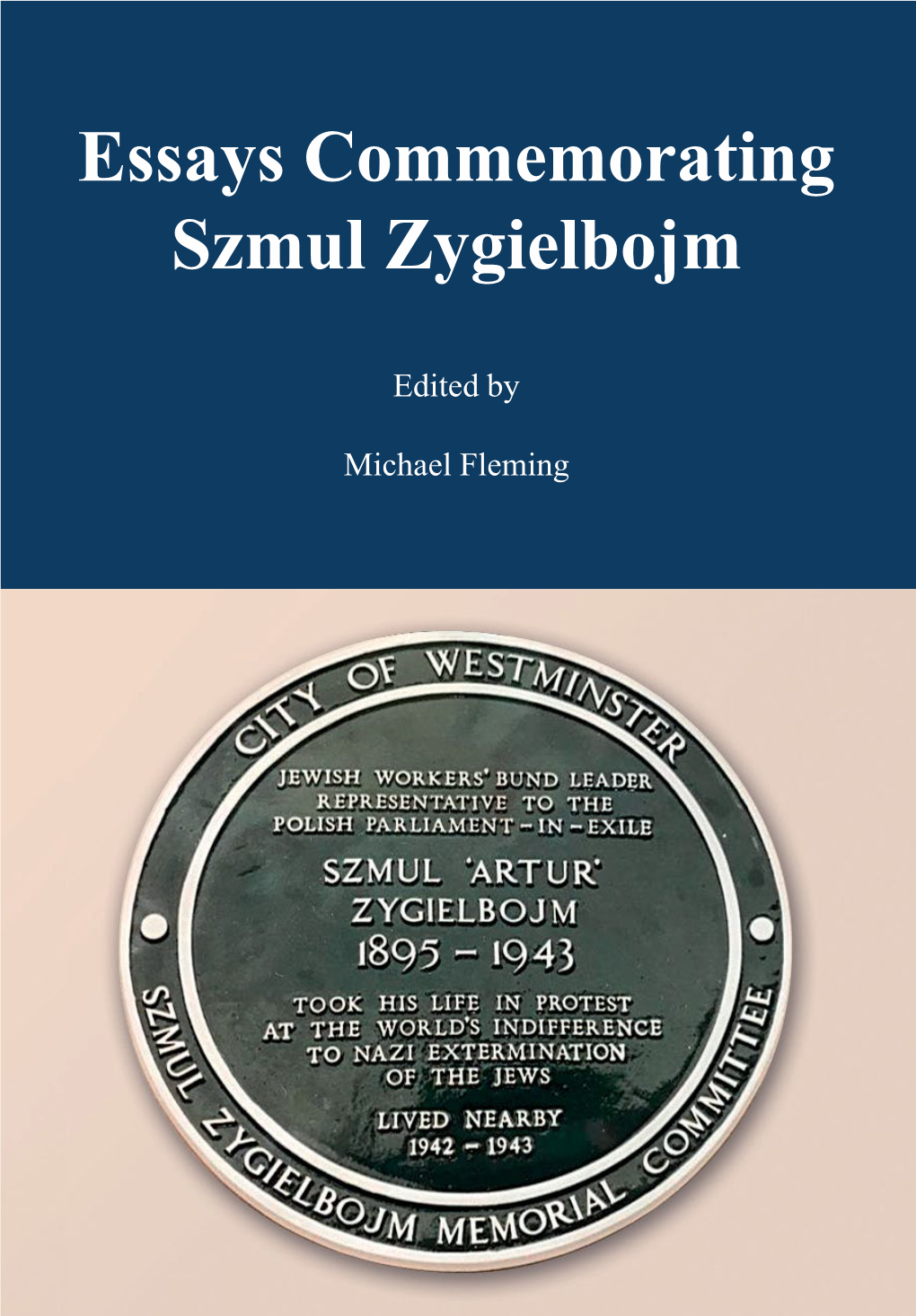

Essays Commemorating Szmul Zygielbojm Edited by Michael Fleming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antisemitism in the Radical Left and the British Labour Party, by Dave Rich

Kantor Center Position Papers Editor: Mikael Shainkman January 2018 ANTISEMITISM IN THE RADICAL LEFT AND THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY Dave Rich* Executive Summary Antisemitism has become a national political issue and a headline story in Britain for the first time in decades because of ongoing problems in the Labour Party. Labour used to enjoy widespread Jewish support but increasing left wing hostility towards Israel and Zionism, and a failure to understand and properly oppose contemporary antisemitism, has placed increasing distance between the party and the UK Jewish community. This has emerged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, a product of the radical 1960s New Left that sees Israel as an apartheid state created by colonialism, but it has been building on the fringes of the left for decades. Since Corbyn became party leader, numerous examples of antisemitic remarks made by Labour members, activists and elected officials have come to light. These remarks range from opposition to Israel’s existence or claims that Zionism collaborated with Nazism, to conspiracy theories about the Rothschilds or ISIS. The party has tried to tackle the problem of antisemitism through procedural means and generic declarations opposing antisemitism, but it appears incapable of addressing the political culture that produces this antisemitism: possibly because this radical political culture, borne of anti-war protests and allied to Islamist movements, is precisely where Jeremy Corbyn and his closest associates find their political home. A Crisis of Antisemitism Since early 2016, antisemitism has become a national political issue in Britain for the first time in decades. This hasn’t come about because of a surge in support for the far right, or jihadist terrorism against Jews. -

Aufstieg Und Fall Von Jürgen Stroop (1943-1952): Von Der Beförderung Zum Höheren SS- Und Polizeiführer Bis Zur Hinrichtung

Aufstieg und Fall von Jürgen Stroop (1943-1952): von der Beförderung zum Höheren SS- und Polizeiführer bis zur Hinrichtung. Eine Analyse zur Darstellung seiner Person anhand ausgewählter Quellen. Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Beatrice BAUMGARTNER am Institut für Geschichte Begutachter: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Klaus Höd Graz, 2019 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen inländischen oder ausländischen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Die vorliegende Fassung entspricht der eingereichten elektronischen Version. Datum: Unterschrift: I Gleichheitsgrundsatz Aus Gründen der Lesbarkeit wird in der Diplomarbeit darauf verzichtet, geschlechterspezifische Formulierungen zu verwenden. Soweit personenbezogene Bezeichnungen nur in männlicher Form angeführt sind, beziehen sie sich auf Männer und Frauen in gleicher Weise. II Danksagung In erster Linie möchte ich mich bei meinem Mentor Univ.-Doz. Dr. Klaus Hödl bedanken, der mir durch seine kompetente, freundliche und vor allem unkomplizierte Betreuung das Verfassen meiner Abschlussarbeit erst möglich machte. Hoch anzurechnen ist ihm dabei, dass er egal zu welcher Tages- und Nachtzeit -

25 Handbook of Bibliography on Diaspora and Transnationalism.Pdf

BIBLIOGRAPH Y A Hand-book on Diaspora and Transnationalism FIRST EDITION April 2013 Compiled By Monika Bisht Rakesh Ranjan Sadananda Sahoo Draft Copy for Reader’s Comments Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism www.grfdt.org Bibleography Preface Large scale international mobility of the people since colonial times has been one of the most important historical phenomenon in the human history. This has impacted upon the social, cultural, political and economic landscape of the entire globe. Though academic interest goes back little early, the phenomenon got the world wide attention as late as 1990s. We have witnessed more proactive engagement of various organizations at national and international level such as UN bodies. There was also growing research interest in the areas. Large number of institutions got engaged in research on diaspora-international migration-refugee-transnationalism. Wide range of research and publications in these areas gave a new thrust to the entire issue and hence advancing further research. The recent emphasis on diaspora’s development role further accentuated the attention of policy makers towards diaspora. The most underemphasized perhaps, the role of diaspora and transnational actors in the overall development process through capacity building, resource mobilization, knowledge sharing etc. are growing areas of development debate in national as well as international forums. There have been policy initiatives at both national and international level to engage diaspora more meaningfully since last one decade. There is a need for more wholistic understanding of the enrite phenomena to facilitate researchers and stakeholders engaged in the various issues related to diaspora and transnationalism. Similarly, we find the areas such as social, political and cultural vis a vis diaspora also attracting more interest in recent times as forces of globalization intensified in multi direction. -

British Responses to the Holocaust

Centre for Holocaust Education British responses to the Insert graphic here use this to Holocaust scale /size your chosen image. Delete after using. Resources RESOURCES 1: A3 COLOUR CARDS, SINGLE-SIDED SOURCE A: March 1939 © The Wiener Library Wiener The © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. Where was the photograph taken? Which country? 2. Who are the people in the photograph? What is their relationship to each other? 3. What is happening in the photograph? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the image. SOURCE B: September 1939 ‘We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people.’ © BBC Archives BBC © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph and the extract from the document. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. The person speaking is British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. What is he saying, and why is he saying it at this time? 2. Does this support the belief that Britain declared war on Germany to save Jews from the Holocaust, or does it suggest other war aims? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the sources. -

Samuel Maharero Portrait

SAMUEL MAHARERO (1856-1923) e id Fig noc hter against ge Considered the first genocide of the 20th century, forerunner to the Holocaust, between 1904-08 the German army committed acts of genocide against groups of blackHEROIC people RESISTANCE in German TO South THE . NATIONAL HERO West Africa. Samuel Maharero’s by the German army has made him a MASSACRE First they came for the Gustav Schiefer communists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Esther Brunstein Anti Nazi Trade Unionist communist; Primo Levi Survivor and Witness (b. 1876) Then they came for the socialists, han Noor k Chronicler of Holocaust (1928- ) Gustav Schiefer, Munich Chairman and I did not speak out—because Anne Frank Courageous Fighter (1919-1987) Esther Brunstein was born in of the German Trade Union I was not a socialist; Lodz, Poland. When the Nazis Association, was arrested, Leon Greenman Diarist (1929-1945) (1914-1944) Primo Levi was born in Turin, beaten and imprisoned in Dachau Then they came for the trade eil Italy. He was sent to Auschwitz invaded in 1939 she was forced to Simone v Witness to a new Born in Frankfurt-am-Maim in Born to an Indian father and concentration camp. Members unionists, and I did not speak in 1944. Managing to survive wear a yellow star identifying her Germany, Anne Frank’s family American mother in Moscow, of trade unions and the Social out—because I was not a trade Holocaust survivor and generation (1910-2008) he later penned the poignant as a Jew. In 1940 she had to live went to Holland to escape Nazi Noor Khan was an outstandingly If this be a Democratic Party were targeted by politician (1927- ) Born in London and taken and moving book in the Lodz ghetto. -

Supplemental Assets – Lesson 6

Supplemental Assets – Lesson 6 The following resources are from the archives at Yad Vashem and can be used to supplement Lesson 6, Jewish Resistance, in Echoes and Reflections. In this lesson, you learn about the many forms of Jewish resistance efforts during the Holocaust. You also consider the risks of resisting Nazi domination. For more information on Jewish resistance efforts during the Holocaust click on the following links: • Resistance efforts in the Vilna ghetto • Resistance efforts in the Kovno ghetto • Armed resistance in the Sobibor camp • Resistance efforts in Auschwitz-Birkenau • Organized resistance efforts in the Krakow ghetto: Cracow (encyclopedia) • Mordechai Anielewicz • Marek Edelman • Zvia Lubetkin • Rosa Robota • Hannah Szenes In this lesson, you meet Helen Fagin. Learn more about Helen's family members who perished during the Holocaust by clicking on the pages of testimony identified with a . For more information about Jan Karski, click here. In this lesson, you meet Vladka Meed. Learn more about Vladka's family members who perished during the Holocaust by clicking on the pages of testimony identified by a . Key Words • The "Final Solution" • Jewish Fighting Organization, Warsaw (Z.O.B.) • Oneg Shabbat • Partisans • Resistance, Jewish • Sonderkommando Encyclopedia • Jewish Military Union, Warsaw (ZZW) • Kiddush Ha-Hayim • Kiddush Ha-Shem • Korczak, Janusz • Kovner, Abba • Holocaust Diaries • Pechersky, Alexandr • Ringelblum, Emanuel • Sonderkommando • United Partisan Organization, Vilna • Warsaw Ghetto Uprising • -

Labour, Antisemitism and the News – a Disinformation Paradigm

Labour, Antisemitism and the News A disinformation paradigm Dr Justin Schlosberg Laura Laker September 2018 2 Executive Summary • Over 250 articles and news segments from the largest UK news providers (online and television) were subjected to in-depth case study analysis involving both quantitative and qualitative methods • 29 examples of false statements or claims were identified, several of them made by anchors or correspondents themselves, six of them surfacing on BBC television news programmes, and eight on TheGuardian.com • A further 66 clear instances of misleading or distorted coverage including misquotations, reliance on single source accounts, omission of essential facts or right of reply, and repeated value-based assumptions made by broadcasters without evidence or qualification. In total, a quarter of the sample contained at least one documented inaccuracy or distortion. • Overwhelming source imbalance, especially on television news where voices critical of Labour’s code of conduct were regularly given an unchallenged and exclusive platform, outnumbering those defending Labour by nearly 4 to 1. Nearly half of Guardian reports on the controversy surrounding Labour’s code of conduct featured no quoted sources defending the party or leadership. The Media Reform Coalition has conducted in-depth research on the controversy surrounding antisemitism in the Labour Party, focusing on media coverage of the crisis during the summer of 2018. Following extensive case study research, we identified myriad inaccuracies and distortions in online and television news including marked skews in sourcing, omission of essential context or right of reply, misquotation, and false assertions made either by journalists themselves or sources whose contentious claims were neither challenged nor countered. -

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Commemoration

Der Partizaner-himen––Hymn of the Partisans Annual Gathering Commemorating Words by Hirsh Glik; Music by Dmitri Pokras Wa rsaw Ghetto Uprising Zog nit keyn mol az du geyst dem letstn veg, The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising khotsh himlen blayene farshteln bloye teg. Commemoration Kumen vet nokh undzer oysgebenkte sho – s'vet a poyk ton undzer trot: mir zaynen do! TODAY marks the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Each April 19th, survivors, the Yiddish cultural Fun grinem palmenland biz vaysn land fun shney, community, Bundists, and children of resistance fighters and mir kumen on mit undzer payn, mit undzer vey, Holocaust survivors gather in Riverside Park at 83rd Street at 75th Anniversary un vu gefaln s'iz a shprits fun undzer blut, the plaque dedicated to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in order to shprotsn vet dort undzer gvure, undzer mut! mark this epic anniversary and to pay tribute to those who S'vet di morgnzun bagildn undz dem haynt, fought and those who perished in history’s most heinous crime. un der nekhtn vet farshvindn mit dem faynt, On April 19, 1943, the first seder night of Passover, as the nor oyb farzamen vet di zun in dem kayor – Nazis began their liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, a group of vi a parol zol geyn dos lid fun dor tsu dor. about 220 out of 50,000 remaining Jews staged a historic and Dos lid geshribn iz mit blut, un nit mit blay, heroic uprising, holding the Nazis at bay for almost a full month, s'iz nit keyn lidl fun a foygl oyf der fray. -

Europe and the World in the Face of the Holocaust

EUROPE AND THE WORLD subject IN THE FACE OF THE HOLOCAUST – PASSIVITY AND COMPLICITY Context6. Societies in all European countries, death camps. Others actively helped the whether fighting against the Germans, Germans in such campaigns ‘in the field’ occupied by or collaborating with them, or carried out in France, the Baltic States, neutral ones, faced an enormous challenge Romania, Hungary, Ukraine and elsewhere. in the face of the genocide committed against Jews: how to react to such an enormous After the German attack on France in June crime? The attitudes of specific nations as well 1940, the country was divided into two zones: as reactions of the governments of the occupied Northern – under German occupation, and countries and the Nazi-free world to the Holocaust Southern – under the jurisdiction of the French continue to be a subject of scholarly interest and state commonly known as Vichy France (La France great controversy at the same time. de Vichy or Le Régime de Vichy) collaborating with the Germans. Of its own accord, the Vichy government Some of them, as noted in the previous work sheet, initiated anti-Jewish legislation and in October guided by various humanitarian, religious, political, 1940 and June 1941 – with consent from head of personal or financial motives, became involved in state Marshal Philippe Petain – issued the Statuts aiding Jews. There were also those, however, who des Juifs which applied in both parts of France and exploited the situation of Jews for material gain, its overseas territories. They specified criteria for engaged in blackmail, denunciation and even determining Jewish origin and prohibited Jews murder. -

Achievements and Challenges

ACHIEVEMENTS AND CHALLENGES Annual Report 2016, Jerusalem ACHIEVEMENTS AND CHALLENGES Annual Report 2016 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance From the Chairman of the Directorate 4 Center, is the leading source for Holocaust From the Chairman of the Council 5 education, documentation and research. From the Mount of Remembrance in Jerusalem, Yad Vashem's Highlights of Yad Vashem's Activities in 2016 6-7 integrated approach incorporates meaningful Education 8-25 educational initiatives, groundbreaking research Remembrance 26-45 and inspirational exhibits. Its use of innovative technological platforms maximizes accessibility Documentation 46-61 to the vast information in the Yad Vashem archival Research 62-73 collections to an expanding global audience. Yad Vashem works tirelessly to safeguard and impart Public Representatives and Senior Staff 74-77 the memory of the victims and the events of the Financial Highlights 2016 78-79 Shoah period; to document accurately one of the darkest chapters in the history of humanity; and to Yad Vashem Friends Worldwide 80-99 contend with the ongoing challenges of keeping the Holocaust relevant today and for future generations. YA D V A 2016 SHEM T POR E | A R L NN UA UA NN L R | A E POR T SHEM 2016 A V D YA 2 3 FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE DIRECTORATE FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE COUNCIL Dear Friends, Dear Friends, After the Holocaust, it was widely hoped that the enormity of its horrors, and their searing significance, Each year, around the Pesach holiday period, I reflect upon my many Pesach celebrations; from those would be recalled forever as deeply relevant to all of humanity. -

The Labour Party

The Labour Party Head Office Southside, 105 Victoria Street, London SW1E 6QT Labour Central, Kings Manor, Newcastle Upon Tyne NE1 6PA 0345 092 2299 | labour.org.uk/contact Dr Moshe Machover, zzzzzzzzzzzz BY EMAIL ONLY: [email protected] 30 November 2020 Ref: L1627330 Case No: CN-4925 Dear Dr Machover, Notice of administrative suspension from membership of the Labour Party Allegations that you may have been involved in a breach of Labour Party rules have been brought to the attention of national officers of the Party. These allegations relate to your conduct online and offline which may be in breach of Chapter 2, Clause I.8 of the Labour Party Rule Book. It is important that these allegations are investigated and the NEC will be asked to authorise a full report to be drawn up with recommendations for disciplinary action if appropriate. We write to give you formal notice that it has been determined that the powers given to the NEC under Chapter 6 Clause I.1.A* of the Party’s rules should be invoked to administratively suspend you from membership of the Labour Party, pending the outcome of an internal Party investigation. The administrative suspension means that you cannot attend any Party meetings including meetings of your own branch, constituency, or annual conference; and you cannot be considered for selection as a candidate to represent the Labour Party at an election at any level**. In view of the urgency to protect the Party’s reputation in the present situation the General Secretary has determined to use powers delegated to him under Chapter 1 Clause VIII.5 of the rules to impose this suspension forthwith, subject to the approval of the next meeting of the NEC. -

Gazeta Spring/Summer 2021

Volume 28, No. 2 Gazeta Spring/Summer 2021 Wilhelm Sasnal, First of January (Side), 2021, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Daniel Blokh, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Aleksandra Sajdak, William Zeisel, LaserCom Design, and Taube Center for Jewish Life and Learning CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 4 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 5 FEATURES Lucy S. Dawidowicz, Diaspora Nationalist and Holocaust Historian ............................ 6 From Captured State to Captive Mind: On the Politics of Mis-Memory Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz ................................................................................................ 12 EXHIBITIONS New Legacy Gallery at POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Tamara Sztyma .................................................................................................................... 16 Wilhelm Sasnal: Such a Landscape. Exhibition at POLIN Museum ........................... 20 Sweet Home Sweet. Exhibition at Galicia Jewish Museum Jakub Nowakowski .............................................................................................................. 21 A Grandson’s