Downloaded Frombrill.Com10/04/2021 02:13:07PM Polished

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

All Chapters.Pmd

CHAPTER 5 KINGDOMS, KINGS AND AN EARLEARLEARLY REPUBLIC Election dadaElection y Shankaran woke up to see his grandparents all ready to go and vote. They wanted to be the first to reach the polling booth. Why, Shankaran wanted to know, were they so excited? Somewhat impatiently, his grandfather explained: “We can choose our own rulers today.” HoHoHow some men became rulers Choosing leaders or rulers by voting is something that has become common during the last fifty years or so. How did men become rulers in the past? Some of the rajas we read about in Chapter 4 were probably chosen by the jana, the people. But, around 3000 years ago, we find some changes taking place in the ways in which rajas were chosen.NCERT Some men now became recognised as rajas by perforrepublishedming very big sacrifices. The© ashvamedha or horse sacrifice was one such ritual. Abe horse was let loose to wander freely and it was guarded by the raja’s men. If the horse wanderedto into the kingdoms of other rajas and they stopped it, they had to fight. If they allowed thenot horse to pass, it meant that they accepted that the raja who wanted to perform the sacrifice was stronger than them. These rajas were then invited to the sacrifice, which was performed by specially trained priests, who were rewarded with gifts. The raja who organised the sacrifice was recognised as being very powerful, and all those who came brought gifts for him. The raja was a central figure in these rituals. He often had a special seat, a throne or a tiger n 46 skin. -

Yakshi: the Journey of the 'Mother Internationally

Journal of Advances and JournalScholarly of Advances and Researches in Scholarly Researches in AlliedAllied Educat ion Education Vol.Vol. IX 3,, Issue Issue No. 6, XV II, Jan-2015April, ISSN-2012, 2230 -7540 ISSN 2230- 7540 REVIEW ARTICLE AN YAKSHI: THE JOURNEY OF THE 'MOTHER INTERNATIONALLY GODDESS' IN INDIAN ART TRADITION INDEXED PEER REVIEWED & Study of Political Representations: REFEREED JOURNAL Diplomatic Missions of Early Indian to Britain www.ignited.in Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. IX, Issue No. XVII, January-2015, ISSN 2230-7540 Yakshi: The Journey of the 'Mother Goddess' In Indian Art Tradition Aditi Mann1 Akanksha Narayan Singh2 1Research Scholar, University of Delhi 2Assistant Professor, University of Delhi Abstract – The present paper points out the variable forms that an image can assume, from the form of living divine being, as symbol of sovereignty, war trophies and as object of sculptural art, depending on the changing context, setting, presentation and most significantly on the perceptions of a viewer. The paper shall deal with female forms of idols particularly of Yakshi and would seek its transition from an independent powerful deity whose worship was widely spread once, to its eventual absorption and marginalization by the dominant religious traditions in ancient times and finally its coexistence with the Brahmanic deities among the rural communities in present times. Furtherw, it will emphasize on the changing perceptions towards "Once Goddess Yakshi" in contemporary period and how she is perceived, experienced and interpreted by various communities and by different people. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - THE JOURNEY OF THE YAKSHI Prithvi etc. The Aryan culture initially stood apart from those who were the worshippers of Linga and Yoni The beginning of civilization in India goes back to third representing the generative organs of male and millennium B. -

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

Book Reviews - Matthew Amster, Jérôme Rousseau, Kayan Religion; Ritual Life and Religious Reform in Central Borneo

Book Reviews - Matthew Amster, Jérôme Rousseau, Kayan religion; Ritual life and religious reform in Central Borneo. Leiden: KITLV Press, 1998, 352 pp. [VKI 180.] - Atsushi Ota, Johan Talens, Een feodale samenleving in koloniaal vaarwater; Staatsvorming, koloniale expansie en economische onderontwikkeling in Banten, West-Java, 1600-1750. Hilversum: Verloren, 1999, 253 pp. - Wanda Avé, Johannes Salilah, Traditional medicine among the Ngaju Dayak in Central Kalimantan; The 1935 writings of a former Ngaju Dayak Priest, edited and translated by A.H. Klokke. Phillips, Maine: Borneo Research Council, 1998, xxi + 314 pp. [Borneo Research Council Monograph 3.] - Peter Boomgaard, Sandra Pannell, Old world places, new world problems; Exploring issues of resource management in eastern Indonesia. Canberra: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Australian National University, 1998, xiv + 387 pp., Franz von Benda-Beckmann (eds.) - H.J.M. Claessen, Geoffrey M. White, Chiefs today; Traditional Pacific leadership and the postcolonial state. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997, xiv + 343 pp., Lamont Lindstrom (eds.) - H.J.M. Claessen, Judith Huntsman, Tokelau; A historical ethnography. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996, xii + 355 pp., Antony Hooper (eds.) - Hans Gooszen, Gavin W. Jones, Indonesia assessment; Population and human resources. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, 1997, 73 pp., Terence Hull (eds.) - Rens Heringa, John Guy, Woven cargoes; Indian textiles in the East. London: Thames and Hudson, 1998, 192 pp., with 241 illustrations (145 in colour). - Rens Heringa, Ruth Barnes, Indian block-printed textiles in Egypt; The Newberry collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997. Volume 1 (text): xiv + 138 pp., with 32 b/w illustrations and 43 colour plates; Volume 2 (catalogue): 379 pp., with 1226 b/w illustrations. -

Dona Sutta (A 4.36) Deals, in Poetic Terms, with the Nature of the Awakened Saint in a Brief but Dramatic Dialogue

A 4.1.4.6 Aṅguttara Nikya 4, Catukka Nipāta 1, Paṭhama Paṇṇāsaka 4, Cakka Vagga 6 (Pāda) Doṇa Sutta 13 The Doṇa Discourse (on the Footprint) | A 4.36/2:37 f Theme: The Buddha is the only one of a kind Translated by Piya Tan ©2008, 2011 1 Versions of the Sutta Scholars have identified five versions of the (Pāda) Doṇa Sutta, that is, (1) Pali (Pāda) Doṇa Sutta A 4.36/2:37 f; (2) Chinese 輪相經 lúnxiàng jīng1 SĀ 101 = T2.99.28a20-28b18;2 (3) Chinese 輪相經 lúnxiàng jīng3 SĀ2 267 = T2.100.467a26-b24; (4) Chinese (sutra untitled)4 EĀ 38.3 = T2.125.717c18-718a12;5 (5) Gāndhārī *Dhoṇa Sutra6 [Allon 2001:130-223 (ch 8)]. There is no known Sanskrit or Tibetan version. Although the text is well known today as the “Doṇa Sut- ta,”7 the sutta’s colophon (uddāna) lists it as the mnemonic loke (“in the world”), which comes from the phrase jāto loke saṁvaddho at its close (A 3:39,1 f); hence, it should technically be called the Loka Sutta (A 2:44,15). The colophons of the Burmese and Siamese editions, however, give doṇo as a variant read- ing.8 The untitled Chinese version, EĀ 38.3 is unique in mentioning that Doṇa (simply referred to as 彼梵 志 póluómén, “the brahmin”), after listening to the Buddha’s instructions on the five aggregates and the six internal faculties and six external sense-objects, and practising the teaching, in due course, “attained the pure Dharma-eye” (得法眼淨 dé fǎ yǎnjìng) that is, streamwinning (T2.125.718a12). -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

A Study of Buddhist Sites in Karnataka

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicjournal.in Volume 3; Issue 6; November 2018; Page No. 215-218 A study of Buddhist sites in Karnataka Dr. B Suresha Associate Professor, Department of History, Govt. Arts College (Autonomous), Chitradurga, Karnataka, India Abstract Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha wandered the country side teaching what he had learned. He organized a community of monks known as the ‘Sangha’ to continue his teachings ofter his death. They preached the world, known as the Dharma. Keywords: Buddhism, meditation, Aihole, Badami, Banavasi, Brahmagiri, Chandravalli, dermal, Haigunda, Hampi, kanaginahally, Rajaghatta, Sannati, Karnataka Introduction of Ashoka, mauryanemperor (273 to 232 B.C.) it gained royal Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the support and began to spread more widely reaching Karnataka history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was and most of the Indian subcontinent also. Ashokan edicts founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of which are discovered in Karnataka delineating the basic tents Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got of Buddhism constitute the first written evidence about the enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha presence of the Buddhism in Karnataka. -

Naneghat Inscription from the Perspective of the Vedic Rituals

Multi-Disciplinary Journal ISSN No- 2581-9879 (Online), 0076-2571 (Print) www.mahratta.org, [email protected] Naneghat Inscription from the Perspective of the Vedic Rituals Ambarish Khare Assistant Professor, SBL Centre of Sanskrit and Indological Studies Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth [email protected] Abstract A cave at Naneghat contains a long inscription stating the details of a number of Vedic sacrifices performed by the ruler of the Satavahana dynasty. It throws light on the religious and social history of ancient Maharashtra. The present paper is in attempt to study the inscription from the perspective of the Vedic rituals and to note some interesting facts that come before us. Key-words: Naneghat, Satavahana, Inscription, Vedic Ritual, Shobhana Gokhale, Ashvamedha Introduction Naneghat is one of the ancient trade routes in western India, joining the coastal region to the hinterland. It is situated 34 km to the west of Junnar. Junnar is a taluka place in the district of Pune, Maharahtra. There are several groups of Buddhist caves situated around Junnar. But the cave under consideration, which is situated right in the beginning of Naneghat trade route, is not a religious monument. It houses the royal inscriptions of Satavahanas and mentions several deities and rituals that are important in the Vedic religion. They are written in Brahmi script and in Prakrit language. A long inscription occupies the left and right walls of the cave. It is a generally accepted fact that this inscription was written by Naganika, the most celebrated empress of the Satavahana dynasty. It records the performance of sacrifices and donations given by the royal couple, Siri Satakarni and Naganika. -

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots Buddhism (Buddha) Followed by Hindūism (Kṛṣṇā) The religion of the Vedic period (also known as Vedism or Vedic Brahmanism or, in a context of Indian antiquity, simply Brahmanism[1]) is a historical predecessor of Hinduism.[2] Its liturgy is reflected in the Mantra portion of the four Vedas, which are compiled in Sanskrit. The religious practices centered on a clergy administering rites that often involved sacrifices. This mode of worship is largely unchanged today within Hinduism; however, only a small fraction of conservative Shrautins continue the tradition of oral recitation of hymns learned solely through the oral tradition. Texts dating to the Vedic period, composed in Vedic Sanskrit, are mainly the four Vedic Samhitas, but the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and some of the older Upanishads (Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana) are also placed in this period. The Vedas record the liturgy connected with the rituals and sacrifices performed by the 16 or 17 shrauta priests and the purohitas. According to traditional views, the hymns of the Rigveda and other Vedic hymns were divinely revealed to the rishis, who were considered to be seers or "hearers" (shruti means "what is heard") of the Veda, rather than "authors". In addition the Vedas are said to be "apaurashaya", a Sanskrit word meaning uncreated by man and which further reveals their eternal non-changing status. The mode of worship was worship of the elements like fire and rivers, worship of heroic gods like Indra, chanting of hymns and performance of sacrifices. The priests performed the solemn rituals for the noblemen (Kshsatriya) and some wealthy Vaishyas. -

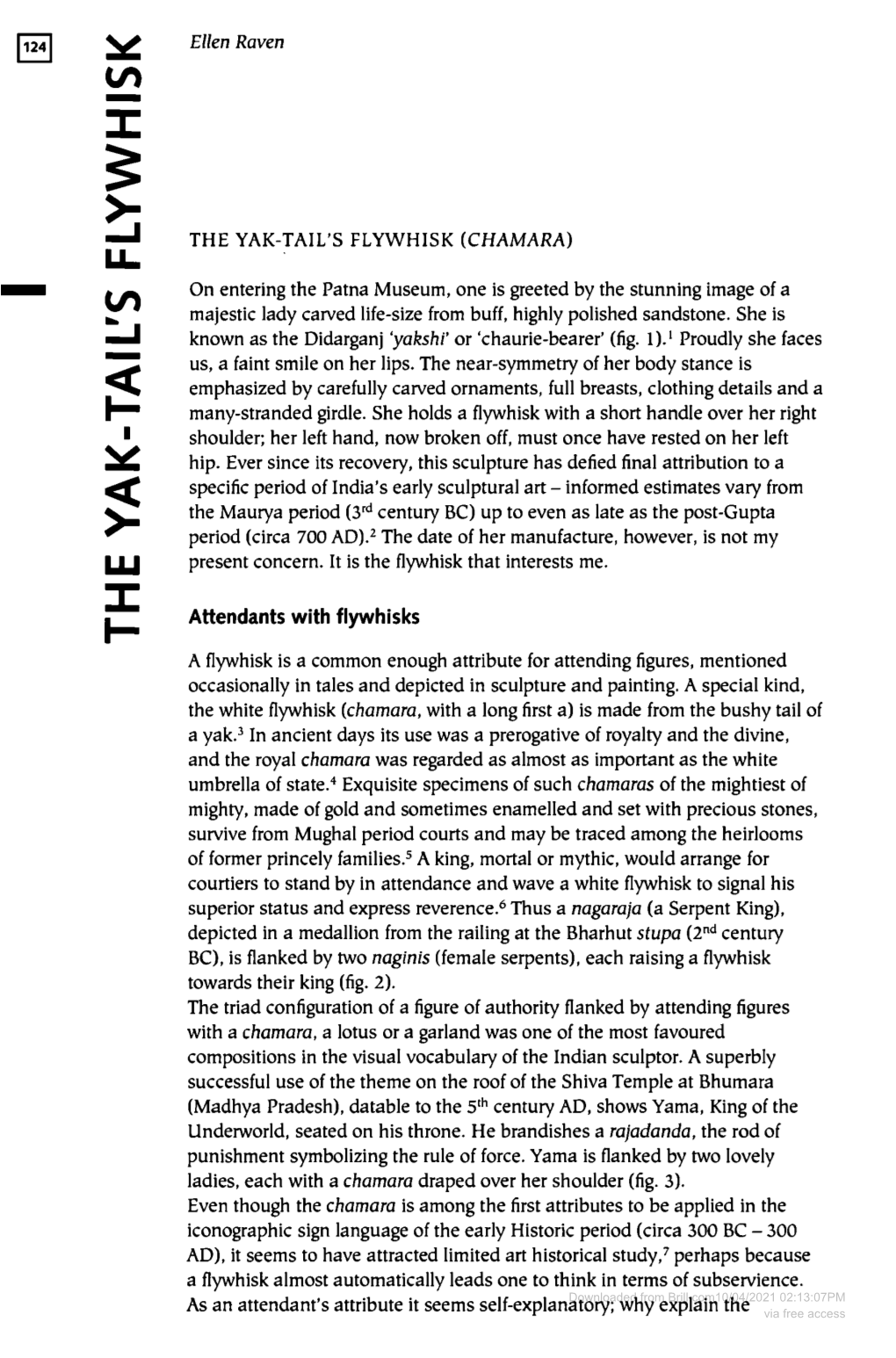

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Jain Award Boy Scout Workbook Green Stage 2

STAGE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. About the Jain Award: Stage 2 2. About Yourself 3. Part I Word 4. Part II Worship 5. Part III Witness 6. Jain Religion Information for Boy Scouts of America 7. Application Form for the Jain Medal Award 2 ABOUT THE JAIN AWARD PLAN STAGE 2 WORD: You will with your parents and spiritual leader meet regularly to complete all the requirements History of Jainism-Lives of Tirthankars: for this award. Mahavir Adinath Parshvanath RECORD Jain Philosophy Significance of Jain Symbols: Ashtamanga As you continue through this workbook, record and others the information as indicated. Once finished Four types of defilement (kashäy): your parents and spiritual leader will review anger ego and then submit for the award. greed deceit The story of four daughters-in-law (four types of spiritual aspirants) Five vows (anuvrats) of householders Jain Glossary: Ätmä, Anekäntväd, Ahinsä, Aparigrah, Karma, Pranäm, Vrat,Dhyän. WORSHIP: Recite Hymns from books: Ärati Congratulations. You may now begin. Mangal Deevo Practices in Daily Life: Vegetarian diet Exercise Stay healthy Contribute charity (cash) and volunteer (kind) Meditate after waking-up and before bed WITNESS: Prayers (Stuties) Chattäri mangala Darshanam dev devasya Shivamastu sarvajagatah Learn Temple Rituals: Nissihi Pradakshinä Pranäm Watch ceremonial rituals (Poojä) in a temple 3 ABOUT YOURSELF I am _____________________years old My favorite activities/hobbies are: ______________________________________ This is my family: ______________________________________ ______________________________________