1 Epigraphic Culture in the Bay of Naples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F. Pingue , G.. De Natale , , P. Capuano , P. De , U

Ground deformation analysis at Campi Flegrei (Southern Italy) by CGPS and tide-gauge network F. Pingue1, G.. De Natale1, F. Obrizzo1, C. Troise1, P. Capuano2, P. De Martino1, U. Tammaro1 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia . Osservatorio Vesuviano, Napoli, Italy 2 Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica, Università di Salerno, Italy CGPS CAMPI FLEGREI NETWORK TIDE GAUGES ABSTRACT GROUND DEFORMATION HISTORY CGPS data analysis, during last decade, allowed continuous and accurate The vertical ground displacements at Campi Flegrei are also tracked by the sea level using tide gauges located at the Campi Flegrei caldera is located 15 km west of the Campi Flegrei, a caldera characterized by high volcanic risk due to tracking of ground deformation affecting Campi Flegrei area, both for Nisida (NISI), Port of Pozzuoli (POPT), Pozzuoli South- Pier (POPT) and Miseno (MISE), in addition to the reference city of Naples, within the central-southern sector of a the explosivity of the eruptions and to the intense urbanization of the vertical component (also monitored continuously by tide gauge and one (NAPT), located in the Port of Naples. The data allowed to monitor all phases of Campi Flegrei bradyseism since large graben called Campanian Plain. It is an active the surrounding area, has been the site of significant unrest for the periodically by levelling surveys) and for the planimetric components, 1970's, providing results consistent with those obtained by geometric levelling, and more recently, by the CGPS network. volcanic area marked by a quasi-circular caldera past 2000 years (Dvorak and Mastrolorenzo, 1991). More recently, providing a 3D displacement field, allowing to better constrain the The data have been analyzed in the frequency domain and the local astronomical components have been defined by depression, formed by a huge ignimbritic eruption the caldera floor was raised to about 1.7 meters between 1968 and inflation/deflation sources responsible for ground movements. -

Notes Du Mont Royal ←

Notes du mont Royal www.notesdumontroyal.com 쐰 Cette œuvre est hébergée sur « No- tes du mont Royal » dans le cadre d’un exposé gratuit sur la littérature. SOURCE DES IMAGES Google Livres l BHAR-TRIHABIS SENTENTIAÈ I. CARMEN (mon 01mm NOMINE CIBCUMFERTUB i EROTICUM. AD conrcum MSTT. FIDEM «EDIDIT LATINE VERTU ET communs ’ A I ’ msmuxrr PETRUS A BQHDLEN. fi BEROLINI IMPBNSIS PERDINANDI DUEMMIÆRI MDCCCXXXIII. nus AQADEIIÇIS. BHARTPJHABJS SENTENTIAÈ CARMEN QUOD 0mm, NOMINE CIRCUMFERTUB I EBOTICUM. AD CODICUM MSTT. FIDEM .EDIDIT LATINE VERTIT ET COMMENTARIIS i INSTRUXIT t PETRUS A BQHULEN. «me» I BEROLINI musas rnnnmmm nusmmam MDCCCXXXIII. TYPIS AQADEHICIS. VIRO SUMME REVERENDO IOANNI SCHULZIO THEOL. DO’CTORI BORUSSORUM REG! POTENTISSIMO A CONSILHS INTIME EQUITI ILLUSTBI CET. HUMANITATIS ET INGENUAE DOCTRINAE FAUTOPJ INSIGNI HASCE BHARTRIHARIS SENTENTIAS . FRUCTUUM EX ITINEBE LITTERARIO NUÎ’ER PERCEPTORUM PRIMITIAS ANIM! BENEFICIORUM IN SE COLLATORUM MEMORIS TESTES ESSE VOLUIT EDITOR. PRAEFATIO. 1 LOndini quum ante biennium, summi Borussiae Ministerü munificentia commorari mihivliceret, ut, quad diuverat in vous, litteris Indicis pro viribus meîs consulerem, nihil prîus equidem et antiquius habui, quam ut sifim meam in Antiquitates Indicae gentis ardentîssimam quocunque modo explerem: nOn solum libris rarioribus legendis excerpendîsve et editionibus textuum Sanscritorum comparandis atque emendis, sed scul- pturis quoque et Picturis, quee in Museis anservantur, inspiciendis et virorum doctorum colloquio, ubi dubii aliquid atque obscuritatis chori- retur, illustrandis, inprimis vero codicibus manuscriptis avulvendis de? scribendisque, donec pestis,’ pro dolor! Gangetica in patria urbe exona et iamiam saeviens post» exiguum temporis spatium studia interrupit dile- ctissima et patremfamilias idomum revocavit. Inter ca quae raptim ipse collegi, de iis enim’quae Roçenio meo et Stenzlero, intima mihi ami- citia coniunctis debeo: Chhandogyae codîcem, apographa Ritœanhari, Gimgovindi, Brahmavaivartapurani rell. -

Boccaccio Angioino Materiali Per La Storia Culturale Di Napoli Nel Trecento

Giancarlo Alfano, Teresa D'Urso e Alessandra Perriccioli Saggese (a cura di) Boccaccio angioino Materiali per la storia culturale di Napoli nel Trecento Destini Incrociati n° 7 5 1-6.p65 5 19/03/2012, 14:25 Il presente volume è stato stampato con i fondi di ricerca della Seconda Università di Napoli e col contributo del Dipartimento di Studio delle componenti culturali del territorio e della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia. Si ringraziano Antonello Frongia ed Eliseo Saggese per il prezioso aiuto offerto. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’éditeur ou de ses ayants droit, est illicite. Tous droits réservés. © P.I.E. PETER LANG S.A. Éditions scientifiques internationales Bruxelles, 2012 1 avenue Maurice, B-1050 Bruxelles, Belgique www.peterlang.com ; [email protected] Imprimé en Allemagne ISSN 2031-1311 ISBN 978-90-5201-825-6 D/2012/5678/29 Information bibliographique publiée par « Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek » « Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek » répertorie cette publication dans la « Deutsche Nationalbibliografie » ; les données bibliographiques détaillées sont disponibles sur le site http://dnb.d-nb.de. 6 1-6.p65 6 19/03/2012, 14:25 Indice Premessa ............................................................................................... 11 In forma di libro: Boccaccio e la politica degli autori ...................... 15 Giancarlo Alfano Note sulla sintassi del periodo nel Filocolo di Boccaccio .................. 31 Simona Valente Appunti di poetica boccacciana: l’autore e le sue verità .................. 47 Elisabetta Menetti La “bona sonoritas” di Calliopo: Boccaccio a Napoli, la polifonia di Partenope e i silenzi dell’Acciaiuoli ........................... 69 Roberta Morosini «Dal fuoco dipinto a quello che veramente arde»: una poetica in forma di quaestio nel capitolo VIII dell’Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta ................................................... -

Constitutio 'Universi Dominici Gregis'

1996-02-26- SS Ioannes Paulus II - Constitutio ‘Universi Dominici Gregis’ IOANNIS PAULI PP. II SUMMI PONTIFICIS CONSTITUTIO APOSTOLICA «UNIVERSI DOMINICI GREGIS» DE SEDE APOSTOLICA VACANTE DEQUE ROMANI PONTIFICIS ELECTIONE Ioannes Paulus PP. II Servus Servorum Dei ad perpetuam rei memoriam UNIVERSI DOMINICI GREGIS Pastor est Romanae Ecclesiae Episcopus, in qua Beatus Petrus Apostolus, divina disponente Providentia, Christo per martyrium extremum sanguinis testimonium reddidit. Plane igitur intellegitur legitimam apostolicam in hac Sede successionem, quacum « propter potentiorem principalitatem, necesse est omnem convenire Ecclesiam »,(1) usque peculiari diligentia esse observatam. Hanc propter causam Summi Pontifices, saeculorum decursu, suum ipsorum esse officium aeque ac praecipuum ius existimaverunt opportunis normis Successoris electionem moderari. Sic, proximis superioribus temporibus, Decessores Nostri Sanctus Pius X (2), Pius XI (3), Pius XII (4), Ioannes XXIII (5) et novissime Paulus VI (6), pro peculiaribus temporum necessitatibus, providas congruentesque curaverunt regulas de hac quaestione ferendas, ut convenienter procederent apta praeparatio atque accurata evolutio consessus electorum cui, vacante Apostolica Sede, grave omninoque difficile demandatur officium Romani Pontificis eligendi. Si quidem nunc et Ipsi hoc aggredimur negotium, id certe facimus haud parvi aestimantes normas illas quas e contrario penitus colimus quasque magna ex parte confirmandas censemus, saltem quod ad praecipua elementa et principia primaria attinet -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

CALENDARS by David Le Conte

CALENDARS by David Le Conte This article was published in two parts, in Sagittarius (the newsletter of La Société Guernesiaise Astronomy Section), in July/August and September/October 1997. It was based on a talk given by the author to the Astronomy Section on 20 May 1997. It has been slightly updated to the date of this transcript, December 2007. Part 1 What date is it? That depends on the calendar used:- Gregorian calendar: 1997 May 20 Julian calendar: 1997 May 7 Jewish calendar: 5757 Iyyar 13 Islamic Calendar: 1418 Muharaim 13 Persian Calendar: 1376 Ordibehesht 30 Chinese Calendar: Shengxiao (Ox) Xin-You 14 French Rev Calendar: 205, Décade I Mayan Calendar: Long count 12.19.4.3.4 tzolkin = 2 Kan; haab = 2 Zip Ethiopic Calendar: 1990 Genbot 13 Coptic Calendar: 1713 Bashans 12 Julian Day: 2450589 Modified Julian Date: 50589 Day number: 140 Julian Day at 8.00 pm BST: 2450589.292 First, let us note the difference between calendars and time-keeping. The calendar deals with intervals of at least one day, while time-keeping deals with intervals less than a day. Calendars are based on astronomical movements, but they are primarily for social rather than scientific purposes. They are intended to satisfy the needs of society, for example in matters such as: agriculture, hunting. migration, religious and civil events. However, it has also been said that they do provide a link between man and the cosmos. There are about 40 calendars now in use. and there are many historical ones. In this article we will consider six principal calendars still in use, relating them to their historical background and astronomical foundation. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

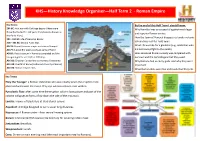

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Piscina Mirabilis the Way of Water

Piscina Mirabilis The way of Water Lara Hatzl Institut für Baugeschichte und Denkmalpflege EM2 Betreuer: Florina Pop; Markus Scherer Inhaltsverzeichnis Abstract Inhalt Die Piscina Mirabilis ist eine römische Zisterne in der Gemeinde Bacoli am Golf von Neapel. Sie wurde unter Kaiser Augustus im 1. Jahrhundert n. Chr. im Inneren eines Tuffsteinhügels angelegt; ihre Auf- 1 Piscina Mirabilis gabe war es, den Portus Julius, das Hauptquartier der Flotte im westlichen Mittelmeer nahe Pozzuoli, mit Trinkwasser zu versorgen. Das Wasser wurde durch einen 96 km langen Aquädukt herangeführt, 1 The way of Water der vom Serino östlich des Vesuvs an dessen nördlicher Flanke entlang zum Misenosee führte. Die gut erhaltene Zisterne misst rund 72 x 27 m, der Raum wird geprägt durch ein regelmäßiges Raster von 1 Vorabzug Stützen und Bogen mit Gewölben. 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis In meiner Entwurfsidee folge ich dem Wasser. Der Weg von der Quelle in Serino und die Piscina als 3 Abstract Ausgangspunkt. Das Wasser spielt in diesem Gebiet eine Zentrale Rolle. Die Zisterne versorgte den Kriegshafen in Miseno mit Frischwasser. in Unmittelbarer nähe befindet sich Baiae mit ihren Thermena- 5 Verortung lagen welche schon damals als atraktives und erholsames Gebiet wirkte. 11 Inspirationen 14 Künstler - Numen / for use Wasser ist ein wichtiges Element in meinem Entwurf. Ich bedecke die gesamte Dachfläche mit einer Wasserschicht. Durch die Öffnungen in der Dachfläche und durch die Wasseroberfläche bekommt man 15 Künstler - Loris Cecchini auch im Inneren den Eindruck als wäre man im Wasser. Das ruhige Wasser spiegelt auf den daraufste- henden Bau. (Inspiration Architekt Tadao Ando /Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth und Langen Foun- 16 Gebäudeanalyse Innenraum Bögen dation) Dachdurchbruch 18 Gebäudeanalyse-Innenraum Fotos Der Bogen ist in der römischen Architektur weit verbreitet. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

Wakans Stolicy Apostolskiej I Wybór Papieża W Świetle Motu Proprio Jana XXIII "Summi Pontificis Electio"

Stefan Sołtyszewski Wakans Stolicy Apostolskiej i wybór papieża w świetle motu proprio Jana XXIII "Summi Pontificis Electio" Prawo Kanoniczne : kwartalnik prawno-historyczny 7/1-2, 233-258 1964 KS. STEFAN, SOŁTYSZEWSKI WAKANS STOLICY APOSTOLSKIEJ 1 WYBÓR PAPIEŻA W ŚWIETLE MOTU PROPRIO JANA XXIII „SUMMI PONTIFICIS ELECTIO” W ciągu wieków „pro mutatis temporum rationibus” zo stały wydane liczne dokumenty papieskie, normujące wakans Stolicy Apostolskiej i wybór papieża, sprawy o największym znaczeniu dla Kościoła. Wśród tych dokumentów konstytu cje Piusa IV,1 Grzegorza XV2 i Klemensa XII 3 zajmują na czelne miejsce. Z czasem przepisy w nich zawarte urosły do bardzo wielkiej liczby, a niektóre z nich z upływem czasu zdeaktualizowały się. Trzeba było dużego wysiłku, aby zorien tować się, które przepisy nadal obowiązują, a które przestały obowiązywać. Chcąc zaradzić tej niewygodzie (incommodum), Papież Pius X zebrał prawo, dotyczące wakansu Stolicy Apo stolskiej i wyboru papieża „in unam Constitutionem”, zacho wując w całości, o ile to było możliwe, przepisy dawniej szych konstytucji, które sankcjonowała „czcigodna starożyt ność”, niektóre jednak zmieniając, co wydawało się wskaza nym 4. Odtąd przepisami Konstytucji Piusa X „Vacante Sede Apostolica” z 25 grudnia 1904 r. miało wyłącznie rządzić się Kolegium kardynalskie w czasie wakansu Stolicy Apostolskiej , 1 Magnum Bullarium Romanum, Luxemburg! 1727, II, 97—100: Pii IV Constitutio „In eligendis”, VII Idus Oct. 1562. 2 Tamże, III, 444—448: Gregorii XV Constitutio „Aeterni Patris”, XVII kal. Dec. 1621. 3 Magnum Bullarium Romanum, Luxembergi 1740, XIV, 248—258: Clementis XII Constitutio „Apostolatus officium", IV Non. Oct. 1732. * Codex iuris canonici, Romae 1934, 763: Docum: I.: Pii X Const. „Vacante Sede Apostolica”. -

Tourism in Augustan Society (44 BC–AD 69)

Chapter 4 Tourism in Augustan Society (44 BC–AD 69) LOYKIE LOMINE This chapter discusses the significance of tourism in classical antiquity. It focuses on Augustan Rome and its Empire between 44 BC and AD 69, the period between the assassination of Caesar and the end of the reign of Nero and of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. It shows that, contrary to common beliefs and assumptions, tourism existed long before the famous Grand Tour of Mediterranean Europe by English aristocrats. The sophisti- cated Augustan society offered everything that is commonly regarded as typically modern (not to say post-modern) in terms of tourism: museums, guide-books, seaside resorts with drunk and noisy holidaymakers at night, candle-lit dinner parties in fashionable restaurants, promiscuous hotels, unavoidable sightseeing places, spas, souvenir shops, postcards, over-talkative and boring guides, concert halls and much more besides. Methodologically, this chapter is based upon three main types of primary sources: archaeological evidence, inscriptions and Latin liter- ature. Most Latin authors mention facts related to travel and tourism. Their names are here given in their common English version (e.g. Virgil for Vergilius) and references are made in a conventional way, mentioning not the page or year of publication of a specific edition but the exact locali- sation of the text, e.g. Propertius 1, 11, 30: book 1, piece 11, line 30, making it possible to find the quoted passage in any version. Archaeological evidence concerns transport (e.g. the paved roads facilitating travel, such as the ‘Queen of Roads’, the Appian Way from Puteoli to Rome, by which Saint Paul came to Rome [Acts 28.13]) and accommodation, notably the inns discovered in the ashes of Pompeii and Herculaneum, whose plans are reminiscent of the European hostelries of the 16th century (Bosi, 1979: 237–56; Mau, 1899; Tucker, 1910: 22).