Click It Documents Supreme Court Judgments Power of the Prime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTIONS 1. Audience - AUD ........................................................................................................ 4 2. Communication Policy & Technology - CPT ............................................................. 14 3. Community Communication - COC ......................................................................... 27 4. Emerging Scholars - ESN ......................................................................................... 42 5. Gender and Communication - GEC .......................................................................... 50 6. History - HIS ........................................................................................................... 61 7. International Communication - INC ........................................................................ 67 8. Journalism ResearcH & Education - JRE + UNESCO .................................................. 83 9. Law - LAW ............................................................................................................ 106 10. Media and Sport - MES ....................................................................................... 113 11. Media Education ResearcH - MER ....................................................................... 117 12. Mediated Communication, Public Opinion & Society - MPS ................................ 122 13. Participatory Communication ResearcH - PCR ..................................................... 129 14. Political Communication - POL ........................................................................... -

Monthly Case Law Update

MONTHLY CASE LAW UPDATE Vol. 1, Issue 3 December, 2016 ________________________________________________________________ CRIMINAL LAWS (1) P L D 2016 Supreme Court 951 Contents Page Present: Anwar Zaheer Jamali, C.J., Mian Criminal Laws 1 Saqib Nisar, Amir Hani Muslim, Ejaz Afzal Khan and Mushir Alam, JJ Law of Tort 2 Qanun-e-Shahadat Order 2 KASHIF ALI---Petitioner Service Law 3 Versus Rent Law 3 The JUDGE, ANTI-TERRORISM, COURT Civil Procedure Code 3 NO.II, LAHORE and others---Respondents Family Law 4 Where the action of an accused results in striking Law of Evidence 4 terror, or creating fear, panic sensation, helplessness Constitutional Law 4 and sense of insecurity among the people in a particular vicinity, it amounts to terror and such an action squarely falls within the ambit of Section 6 of the Act. Control of Narcotic Substances Act (XXV of 1997) KHUDA BAKHSH vs. The STATE (2) 2015 S C M R 735 Contact Ijaz Ahmed Chaudhry, Dost Muhammad Khan and Qazi Faez Isa, JJ 042 -99212951 (Ext.267) Ss. 9(b) & (c) Quantum of Sentence The period of imprisonment in respect of narcotics Email address: [email protected] weighing more than one kilogram, but less than ten kilograms, should be for a period greater than seven years to anything less than fourteen years. Page | 1 A LAHORE HIGH COURT RESEARCH CENTRE PUBLICATION, 2012 (3) 2016 S C M R 2035 with the consequences of their choices. Adult person of sound mind was entitled to [Supreme Court of Pakistan] decide which, if any, of the available forms of treatment to undergo, and his/her Present: Asif Saeed Khan Khosa, Umar consent must be obtained before treatment Ata Bandial and Ijaz ul Ahsan, JJ interfering with his/her bodily integrity was undertaken. -

A Report on the Persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan During the Year 2012

A Report on the Persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan during the Year 2012 (Summary) If your teacher is a Qadiani, refuse learning from him A Report on the Persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan during the Year 2012 Contents Chapter Page Nr. 1. Foreword 1 2. Executive summary 2 3. Four special reports 7 I. Spate of murderous attacks in Karachi 7 II. Police torture to death Mr. Abdul Qaddoos, an innocent prominent Ahamdi, in Rabwah 11 III. Freedom of worship severely curtailed in Rawalpindi 17 IV. Banning of the monthly Misbah and the daily Al-Fazl 23 4. Religiously motivated murders, assaults and attempts 27 5. Prosecution on religious grounds 35 6. The worsening situation in Lahore, capital of the Punjab 49 7. Mosques under attack, and worship denied 66 8. Burial problems, graveyards 77 9. Problems in education 85 10. Open-air rallies and hate campaign 94 11. Denial of political rights ± Elections 2013 119 12. Miscellaneous, and reports from all over 128 a. Reports from cities 128 b. Reports from towns and villages 132 c. Media 138 d. Kidnapping of Ahmadis 151 e. Disturbing threats 153 f. Plight of Rabwah 159 g. Diverse 163 13. From the media 171 Annexes: I. Particulars of police cases registered in 2012 195 II. Updated statistics of police cases and other outrages since 1984 196 III. Laws specific to Ahmadis, and the so-called blasphemy laws 198 IV. Photo of a banner in Sargodha bazaar vetoing sacrificial animals to Ahmadis 199 V. A warning from a big mosque in Lahore 200 VI. -

Annual Report 2015–2016

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN ANNUAL REPORT June 2015 - May 2016 ANNUAL REPORT June 2015 - May 2016 Supreme Court of Pakistan ANNUAL REPORT June 2015 - May 2016 Supreme Court of Pakistan Constitution Avenue, Islamabad Ph: 051-9220581-600 Fa x: 051-9215306 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.supremecourt.gov.pk Branch Registry Lahore Nabha Road. Ph: 042-99212401-4 Fax: 042-99212406 Branch Registry Karachi MR Kiyani Road. Ph: 021-99212306-8 Fax: 021-99212305 Branch Registry Peshawar Khyber Road. Ph: 091-9213601-5 Fax: 091-9213599 Branch Registry Quetta High Court of Balochistan Building Quetta. Ph: 081-9201365 Fax: 081-9202244 Published by: Supreme Court of Pakistan Compiled & edited by: Khawaja Daud Ahmad, Additional Registrar (Administration) Saleem Ahmad, Librarian, Supreme Court of Pakistan ii Supreme Court of Pakistan ANNUAL REPORT June 2015 - May 2016 CONTENTS 1. Foreword by the Chief Justice of Pakistan 1 2. Registrar’s Report 2 3. Profile of the Chief Justice and Judges 5 3.1 Profile of the Chief Justice of Pakistan 6 3.2 Profile of Judges of the Supreme Court of Pakistan 7 3.3 Chief Justices & Judges Retired During June 2015 to 34 May 2016 4. Supreme Court of Pakistan 35 4.1 Introduction 36 4.2 Seat of Supreme Court 37 4.3 Branch Registries 37 4.4 Supreme Court Composition, June 2015 to May 2016 39 4.5 Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court 40 4.6 Procedure for the Appointment of Judges of the 42 Supreme Court of Pakistan 4.7 Judicial Commission of Pakistan 43 4.8 Composition of the Judicial Commission of Pakistan 45 4.9 Judicial Commission of Pakistan Rules, 2010 45 4.10 Oath of Office 46 4.11 The Supreme Judicial Council of Pakistan 47 4.12 Code of Conduct for Judges of the Supreme Court and 48 the High Courts 4.13 The Supreme Judicial Council Procedure of Inquiry, 50 2005 4.14 Supreme Judicial Council – Reference No. -

![2016 S C M R 1195 [Supreme Court of Pakistan] Present: Anwar Zaheer Jamali, C.J., Mian Saqib Nisar, Amir Hani Muslim, Iqbal Hame](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7820/2016-s-c-m-r-1195-supreme-court-of-pakistan-present-anwar-zaheer-jamali-c-j-mian-saqib-nisar-amir-hani-muslim-iqbal-hame-3287820.webp)

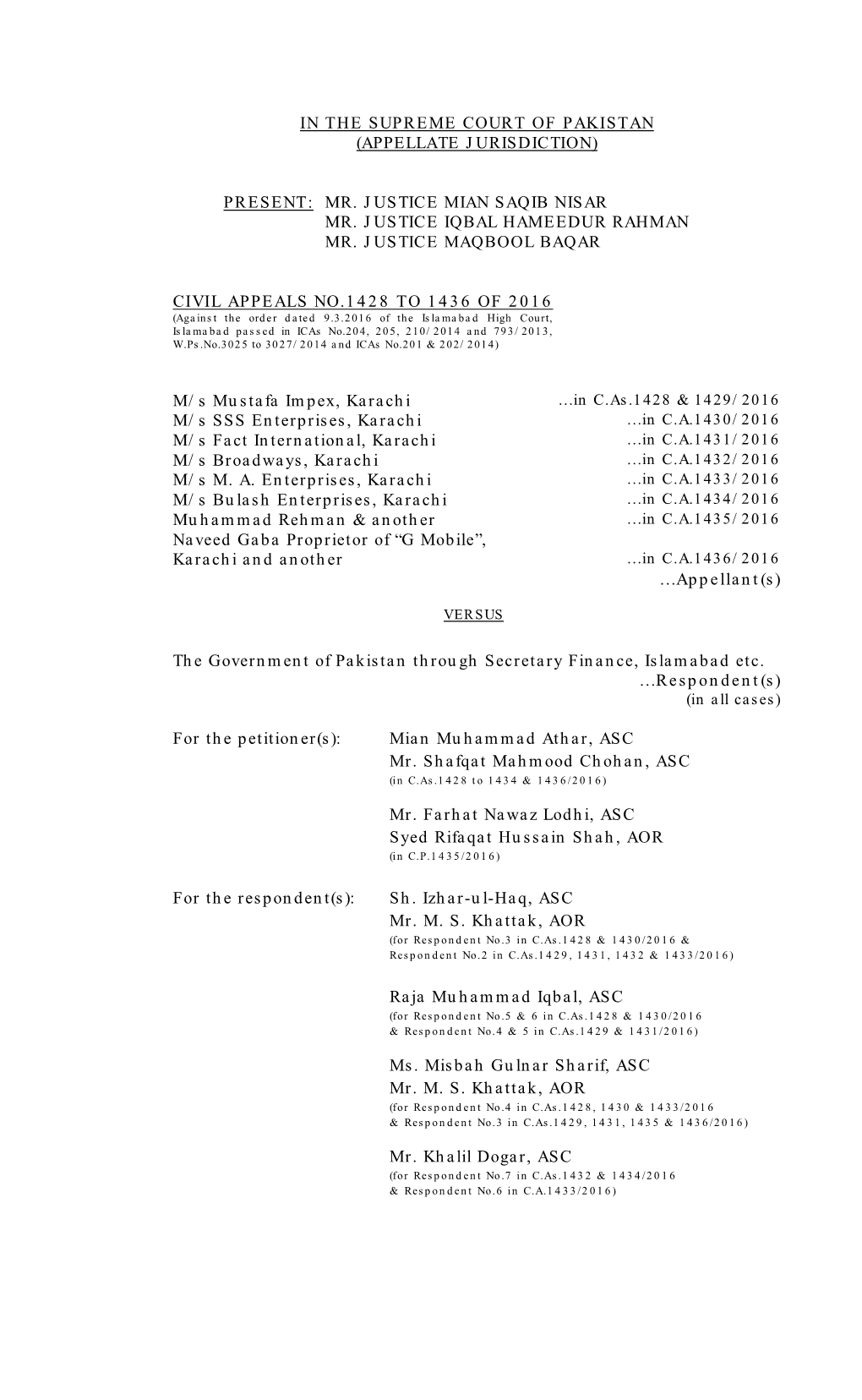

2016 S C M R 1195 [Supreme Court of Pakistan] Present: Anwar Zaheer Jamali, C.J., Mian Saqib Nisar, Amir Hani Muslim, Iqbal Hame

2016 S C M R 1195 [Supreme Court of Pakistan] Present: Anwar Zaheer Jamali, C.J., Mian Saqib Nisar, Amir Hani Muslim, Iqbal Hameedur Rahman and Khilji Arif Hussain, JJ Mst. NOOR BIBI and another---Appellants Versus GHULAM QAMAR and another---Respondents Civil Appeal No. 2133 of 2006, decided on 17th March, 2016. (On appeal from the judgment of the Lahore High Court, Lahore dated 24-10-2001 passed in C.R. No.2239 of 2000) Per Anwar Zaheer Jamali, CJ (a) Islamic law--- ----Inheritance---Shia law---Widow with children---Under the Shia law, a widow with a child from her deceased husband was entitled to a share in both movable and immovable property of her (deceased) husband---Widow with child would be entitled to inherit 1/8 share from the legacy of her deceased husband. Syed Muhammad Munir v. Abu Nasar, Member (Judicial) Board of Revenue, Punjab Lahore and 7 others PLD 1972 SC 346 distinguished. Mohammedan Law by Sir D.F. Mulla (17th Edition) and Syid Murtaza Husain v. Musammat Alhan Bibi 1909 IC (Vol.2) 671 ref. (b) Islamic law--- ----Inheritance---Shia law---Childless widow---Under Shia law childless widow was disqualified from claiming share from the estate of her deceased husband, but only to the extent of lands (immoveable property) left behind by her husband---Childless widow took no share in her husband's land, but she was entitled to her one forth share in the value of trees and buildings standing thereon, as well as in his movable property including debts due to him though they may be secured by a usufructuary mortgage or otherwise. -

Monthly Case Law Update

MONTHLY CASE LAW UPDATE Vol. 1, Issue 4 February, 2017 ____________________________________________________________ CUSTOM LAWS 2017 S C M R 152 [Supreme Court of Pakistan] Present: Mian Saqib Nisar, Maqbool Baqar and Khilji Arif Hussain, JJ Contents Page COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS, CUSTOMS Custom Laws 1 HOUSE, KARACHI---Appellant Versus Civil Service Laws 2 Syed REHAN AHMED---Respondent Constitutional Law 2 The august court while deciding the question as to Transfer of property 3 whether a technical member of the Customs Appellate Tribunal (Tribunal), sitting singly, has the Defamation Ordinance 3 jurisdiction to decide involving questions of law, while reaffirming Director, Intelligence and Civil Procedure Code 3 Investigation (Customs and Excise), Faisalabad and another v. Bagh Ali 2010 Rent Laws 4 PTD 1024 observed that Chairman or Member of Tribunal could decide a case sitting singly provided Labour Laws 4 that such Member or Chairman was already a member of a Bench constituted by the Chairman under S. 194-C(2) of the Customs Act, 1969 and the case must have been allotted to such Bench. Decision by the Chairman to allow himself or any other member of a Bench to sit singly to dispose cases falling within the ambit of S. 194-C(4) should not be as a matter of course or right, rather should be done upon proper application of mind by the Chairman who shall himself make such decision, and not delegate it to any other officer to undertake as an administrative action. Page | 1 A LAHORE HIGH COURT RESEARCH CENTRE PUBLICATION, 2017 CIVIL SERVICE LAW Superior Courts, in exercise of Constitutional jurisdiction can convert one type of proceedings into another. -

Discrimination Against Religious Minorities in Pakistan: an Analysis of Federal and Provincial Laws

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES IN PAKISTAN: AN ANALYSIS OF FEDERAL AND PROVINCIAL LAWS Preface This research paper is part of a large project designed to examine the state of freedom of religion and belief in Pakistan and the problems faced by religious minorities. The project is to be executed by a consortium of six civil society organizations – the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), AGHS Legal Aid Cell, Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP), Simorgh, Faiz Foundation Trust, and Centre for Civic Education (CCE). The project’s justification lies in Pakistan’s need to provide institutional guarantees for the fundamental rights of religious minorities including their primary right to enjoy freedom of religion and belief. The fact that for years minority communities have been suffering a decline in the scale of rights available to them lends special urgency to the project. The project is also important because it focuses on an issue which does not only concern the people of Pakistan (those belonging to the majority (Muslim) as well as minority communities), but also affects the future of religious minorities in India and the relations between the two South Asian neighbours. The Lahore Resolution of 1940, which provided the basis for the division of India in 1947 into two independent states of India and Pakistan, had two parts. While the first part demanded the grant of statehood to territories where the Muslims were in majority, the second part dealt with safeguards for the rights of religious minorities which the two authorities succeeding the British administration were supposed to guarantee. -

Judicial Statistics of Pakistan, Annual Report 2013

JJuuddiicciiaall SSttaattiissttiiccss ooff PPaakkiissttaann 22001133 N a t i o n a l J u d i c i a l ( P o l i c y M a k i n g ) C o m m i t t e e Published by: Secretariat, Law & Justice Commission of Pakistan JJuuddiicciiaall SSttaattiissttiiccss ooff PPaakkiissttaann 22001133 N a t i o n a l J u d i c i a l ( P o l i c y M a k i n g ) C o m m i t t e e Published by: Secretariat, Law & Justice Commission of Pakistan Supreme Court Building, Islamabad www.ljcp.gov.pk Table of Contents Foreword 1 Over View of Performance of Superior Courts and District Judiciary During the years 2013 3 1. Supreme Court of Pakistan 7 1.1 Composition of the Court & Appointment of Judges 7 1.2 Jurisdiction of the Court 7 1.3 The Court Administration 8 1.4 The Human Rights Cell 8 1.5 The Supreme Judicial Council 9 1.6 List of the Hon'ble Judges of the Supreme Court During the Year 2013 10 1.7 List of the Hon'ble Judges of the Supreme Court Retired During the Year 2013 10 1.8 Sanctioned/Working Strength and Vacant Posts in the Supreme Court on 31-12-2013 11 1.9 Consolidated Statement Showing Status of Penalties and Complaints Against Officers/ Officials of the Supreme Court During 2013 13 1.10 Budget Allocation for Principal Seat and Branch Registries of the Supreme Court for 2012-13 13 1.11 Consolidated Statement Showing the Institution, Disposal and Balance of Cases in the Supreme Court During the Year 2013 14 1.12 Institution, Disposal and Balance of Cases at the Principal Seat and Branch Registries of the Supreme Court During the Year 2013 15 1.13 Institution, -

Persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan During the Year 2009

PPPeeerrrssseeecccuuutttiiiooonnn ooofff AAAhhhmmmaaadddiiisss iiinnn PPPaaakkkiiissstttaaannn ddduuurrriiinnnggg ttthhheee YYYeeeaaarrr 222000000999 A Summary Persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan during the Year 2009 www.ThePersecution.org Persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan during the Year 2009 A Summary Contents Page no. 1. Foreword 1 2. Three incidents 2 a. Four school children and an adult booked under the blasphemy law 2 b. A Khatme Nabuwwat conference arranged by the government 6 c. A heart-rending story 9 3. Ahmadis murdered - for their faith 11 4. Murder attempts on Ahmadis 15 5. Prisoners of conscience 18 6. Ahmadiyya mosques under attack 20 7. Tyranny and prosecution go on 24 8. Enormity of the blasphemy law 27 9. Abduction of Ahmadis 29 10. The duet of the state and the mulla 30 11. Business and jobs 38 12. Problems in the field of education 41 13. Burial problems 43 14. Anti-Ahmadiyya open air conferences 45 15. The plight of Rabwah 52 16. Miscellaneous 57 a. The vernacular press and Ahmadis 57 b. Lahore – a centre of anti-Ahmadiyya extremism 60 c. Hostile activities all over Pakistan 63 d. Threats 75 e. Reports of NGOs 76 f. Diverse reports 79 17. From the press 84 18. Conclusion 96 Annexes I. Particulars of police cases registered in 2009 98 II. Updated summary of cases and outrages since 1984 99 III. Laws specific to Ahmadis, and the so-called blasphemy laws 101 IV. Photos of the venue of the official End of Prophethood conference 102 V. A letter issued by a high police officer in Azad Kashmir 103 VI. -

Ansar Al-Nahl

Monthly Monthly Ansar 2006 Majlis Ansaullah,USA Vol. 11 Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. /2006 Vol. 17 No. 4 Vol. 17 No. 4 /2006 Al-Nahl Revelation of the Promised Messiah, ‘alaihissalam Messiah, ‘alaihissalam the Promised Revelation of Q4 of Publication A Quarterly 2006 in Review ·©¿öZ - Al-Nahl Page 1 About Al-Nahl The Al-Nahl (pronounced annahl) Nasir/year. All Ansar are requested to keep up on is published quarterly by Majlis Ansarullah, USA, time payment of their contributions for timely an auxiliary of the Ahmadiyya Movement in publication of the Al-Nahl. Islam, Inc., U.S.A., 15000 Good Hope Road, Subscription Information Silver Spring, MD 20905, U.S.A. The magazine is sent free of charge to all Articles/Essays for the Al-Nahl American Ansar whose addresses are complete Literary contributions, articles, essays, and available on the address database kept by the photographs, etc., for publication in the Al-Nahl Jama‘at, and they are identified as Ansar in the can be sent to the Editor at his address below. database. If you are one of the Ansar living in the It will be helpful if the contributions are saved States and yet are not receiving the magazine, onto a diskette in IBM compatible PC readable please contact your local officers to have your ASCII text format (text only with line breaks), address added, corrected, and/or have yourself MS Publisher, or in Microsoft Word for Windows identified as a member of Ansar. and the diskette or CD is sent, or contents are e- Other interested readers, institutions, or mailed or attached to an e-mail to the editor. -

Power Politics and Role of Baradaries in District Khushab (1982-2008)

i POWER POLITICS AND ROLE OF BARADARIES IN DISTRICT KHUSHAB (1982-2008) NAME: MUHAMMAD WARIS ROLL NO: 03-GCU-PhD-HIS-2004 SESSION: 2009-2012 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GOVT. COLLEGE UNIVERSITY LAHORE ii This thesis is submitted to GC University Lahore in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of degree of PhD in History By NAME: MUHAMMAD WARIS ROLL NO: 03-GCU-PhD-HIS-2004 SESSION: 2009-2012 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GOVT. COLLEGE UNIVERSITY LAHORE iii iv v DEDICATION To the Loving Memory of My Father MUHAMMAD HAYAT AWAN and My SISTer SHAHNAZ AKHTAR (Late) vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all I am extremely thankful to Almighty Allah who gave me strength and commitment to accomplish this monumental task on much debated issue of “POWER POLITICS AND ROLE OF BARADARIES IN DISTRICT KHUSHAB (1982-2008)”. I express my profound gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Farhat Mahmud. He provided me valuable support to accomplish this huge task. I am highly thankful to Dr.Tahir Kamran, Chairperson Department of History GCU Lahore and former Chairperson Dr. Muhammad Ibrahim for sparing time out of their very busy schedule and giving me highly pertinent and valuable pieces of advice, which helped me to overcome my shortcomings related to this thesis. I have deep feelings for Dr. Tahir Mahmud, Coordinator PhD Programme, Dr. Hussain Ahmad Khan, Dr. Tahir Jameel, Dr. Irfan Waheed Usmani, Mr. Noor Hussain, Madam Farzana Arshad, Mr. Ayyaz Gul, Madam Shiffa, Madam Naila Pervez, Department of History GCU Lahore for their kind guidance in organizing this task in practical manner. Madam Humma, Additional Controller of examinations GCU Lahore, She always listen patiently my quiries and immicably solved all technical issues relating to research and examinations. -

The Mustafa Impex Case: ‘A Radical Restructuring of the Law?’

The Mustafa Impex Case: ‘A Radical Restructuring of the Law?’ Mustafa Impex, Karachi v The Government of Pakistan PLD 2016 SC 808 Kamran Adil* Introduction Since 2016, the judgment passed in the Mustafa Impex case1 is all pervasive on the judicial landscape of the country. The reasons are obvious; by expanding the meaning and scope of the Federal Government - which was referred to as a ‗cabinet form of government‘ - the judgment drastically re- ordered the internal dynamics of the federal government and the provincial governments.2 Using the language of Article 90 of the Constitution,3 the judgment stated that in the capacity of the Chief Executive of the country, the Prime Minister ‗executes policy decisions, but does not take them by himself‘.4 The Supreme Court held that the Prime Minister could not move any legislation, finance or fiscal bill, or approve any budgetary or discretionary expenditure, without consulting and obtaining approval from the Cabinet.5 As was expected, the Federal Government filed a review, which was also dismissed.6 This case note outlines the facts of the case, the reasoning and findings of the judgment, and the consequences that might follow from it. Facts of the Case Certain companies which imported cellular phones and textile related items were exempted from sales tax in 2008, through a Federal Government * The author has served as head of the legal affairs division of the Punjab Police and has done his BCL from the University of Oxford, UK. 1 Mustafa Impex, Karachi v The Government of Pakistan PLD 2016 SC 808. 2 Ibid, 846.