Gay Liberation Comes to Dixie—Slowly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham, Alabama Event Hosted by Bill & Linda Daniels Re

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu April 8, 1994 TO: SENATOR DOLE FROM: MARCIE ADLER RE: BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA EVENT HOSTED BY BILL & LINDA DANIELS RE: ELIEHUE & NANCY BRUNSON ELIEHUE BRUNSON, FORMER KC REGIONAL ADMINISTRATOR, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, HAS ADVISED ME THAT HE IS ATTENDING THIS EVENT AND HAS OFFERED TO HELP US IN THE ALABAMA AREA. (I'M SENDING THAT INFO TO C.A.) ELIEHUE WAS APPOINTED BY PRESIDENT BUSH AND DROVE MRS. DOLE DURING THE JOB CORPS CENTER DEDICATION IN MANHATTAN. ALTHOUGH LOW-KEY, HE DID WATCH OUT FOR OUR INTERESTS DURING THE JOB CORPS COMPLETION. HE ALSO DEFUSED A POTENTIAL RACIALLY SENSITIVE SITUATION IN KCK WHEN GALE AND I WERE STUMPED AND CALLED HIM FOR ADVICE. ELIEHUE AND NANCY MOVED TO BIRMINGHAM AFTER TCI - COMMUNICATIONS HIRED HIM TO SERVE AS REGIONAL GENERAL COUNSEL. YOUR LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION WAS A KEY FACTOR IN HIS HIRE. Page 1 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 111 AP 04-08-94 12:06 EST 29 Lines. Copyright 1994. All rights reserved. PM-AL-ELN--Governor-James,200< URGENT< Fob James to Run for Governor Again as Republican< BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) Former Gov. Fob James decided toda to make a fourth bid fo s a Re ublican. Jack Williams, executive director of the Republican Legislative Caucus and chairman of the Draft Fob James Committee, said James would qualify at 3 p.m. today at the State Republicans Headquarters in Birmingham. -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 9/25/78 [2]; Container 92](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8687/presidential-files-folder-9-25-78-2-container-92-168687.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 9/25/78 [2]; Container 92

9/25/78 [2] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/25/78 [2]; Container 92 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TiTLE DAliE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT Memo Harold Brown to Pres. Carter, w/attachments 4 pp., ·r!=!:Defense Summary 9/22/78 A , ' Cabinet Summari. s Andrew Ypung to Pres. Carter~ 1 pg., re:UN activities 9/15/78 9/22/78 A Capinet' Summa:ri s Cal.ifq:no . to Pres. Carter, 3 pp. , re: Personnel "changes 9/22/7.$ c .:~ 0 '· i ~"d. 'I ".'' ' a ~~~·.0 .:t'' '~ ,, 11 , .. "~ •) •· ·~· ',,• \:l,. ,j; ~··~-·< ·-·... • 1 ' .} "I. " 1~ •: , dJ~ ·, '0 ·., " ~ ~r-~ 1\ ~ '·;P. , .. " . ,, ~ 1 , .. ··~ ·:. •·,· '"" <':'• :..·) .,0 / ~ ;w . • '' .• ~ U',• "·',, If' ~' • ·~ ~ ~· • ~ c , " ill" : " ,·, "''t> ''., ' : "."" ~:~~.,,~ . .. r " ·i ' '· ·: ., .~.~ ' 1. ~. ' , .. ;, ~, (• '• ·f." J '',j> '~~'!, ~' -o," :~ ~ ~ e' . " ' ~ ,· J ', I I. FIWE LOCATION Carter Presidenti,al Pap.ers-Staff Offices, Office .of Staff Sec. -Presidenti?l HandwritiRg File, 9/25/78 [2] Box-103 R.ESTRICTtiON CODES (AI Closed by Executive Order 1235S'governing access to national security information. (6) .Closed by statute or by the agency Which originated tine document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gif,t. ~. NATIONAL ARCHIV.S AND RECORDS AOMINISTRA TION. NA FORM 1429 (6-8,5) ' . THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 9/25/78 Tim Kraft The attached was returned in the President's outbox: It is forwarded to you for appropriate han<D:ing. Rick Hutcheson cc: Frank Moore THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 9/25/78 rick-~- although pr.esident is sending note to tim ... -

Democratic Party Candidates

RECEIVED Ytaoama Democratic Par!~ ELEC-flONS DIVISION Post Office Box 950 Montgomery,Afabama 36101-0950 APR 2 7 2016 p- 334.262.2221 AlABAMA f- 334.262.6474 SECRETARY OF STAT! www.aladems.org Certification of Democratic Candidates For the General Election To be Held Tuesday, November 8, 2016 As Chair of the Alabama Democratic Party (State Democratic Executive Committee of Alabama}, I, Nancy Worley, do hereby certify the attached candidates' names to print ballots for the General Election on November 8, 2016. Attached names as follows are subject to change in subsequent certification(s) by correction, or addition/deletion in accordance with Party Bylaws and the Code of Alabama: NAMES ATTACHED IN SPREADSHEET FORMAT Given under my hand and the Seal of the State Democratic Executive Committee of Alabama, this 27th day of April, 2016. Date Date Paid for by the Alabama Democratic Party Office Name U.S. President To be determined at DNC Convention U.S. Senate Ron Crumpton U.S. House, 2nd District Nathan Mathis U.S. House, 3rd District Jesse Smith U.S. House, 5th District Will Boyd, Jr. U.S. House, 6th District David J. Putman U.S. House, 7th District Terri A. Sewell *State School Board, District 1 Candidate withdrew after close of qualifying State School Board, District 3 Jarralynne Agee State School Board, District 5 Ella B. Bell Circuit Judge, 1st Circuit (Clarke, Choctaw, and Washington) Pl 1 Gaines McCorquodale Circuit Judge, 1st Circuit (Clarke, Choctaw, and Washington) Pl 2 C. Robert Montgomery Circuit Judge, 3rd Circuit (Bullock, and Barbour) Burt Smithart Circuit Judge, 4th Circuit (Bibb.Perry, Hale, Dallas, and Wilcox) Pl 2 Don McMillan Circuit Judge, 4th Circuit(Bibb, Dallas, Hale, Perry, and Wilcox) Pl 3 Marvin Wayne Wiggins Circuit Judge, 5th Circuit (Randolph, Tallapoosa, Macon and Chambers) Pl 1 Ray D. -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

Remarks at the University of Alabama-Birmingham in Birmingham

Administration of George W. Bush, 2002 / July 15 1197 NOTE: The interview began at 10:55 a.m. in the But if you guys do get on, you’ll find it to Roosevelt Room at the White House. The tran- be a comfortable plane. [Laughter] But I’m script was released by the Office of the Press Sec- proud that Sonny Callahan and Terry Everett retary on July 15. In his remarks, the President and Bob Riley and Bob Aderholt and Spen- referred to President Aleksander Kwasniewski of Poland, and his wife, Jolanta Kwasniewska; and cer Bachus are with us, too. Thank you all President Vladimir Putin of Russia. The President for coming. These are fine Members, and also referred to MAP, the Military Assistance Pro- they’re good people to work with, and they gram; AGOA, the African Growth and Oppor- put their country first. And I appreciate that tunity Act; and the Quartet, a Middle East policy a lot. planning group consisting of the United States, I know the Lieutenant Governor is here, the United Nations, Russia, and the European and the attorney general is here, and the Union. A tape was not available for verification mayor is here, mayor of Birmingham. I want of the content of this interview. to thank you three for coming as well. I ap- preciate your hospitality. Remarks at the University of I personally want to thank the good folks Alabama-Birmingham in here at UAB, University of Alabama-Bir- Birmingham, Alabama mingham, for allowing us to use, first of all, this fantastic facility. -

Franklin 2010

SAMPLE BALLOT ABSENTEE This is a common ballot, however, BACK OF BALLOT OFFICIAL BALLOT FRANKLIN COUNTY GENERAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT ELECTION some offices will appear only in FRANKLIN COUNTY, ALABAMA NOVEMBER 2, 2010 certain precincts which will apply to your districts. TO VOTE, COMPLETE THE ARROW(S) POINTING TO YOUR CHOICE(S), LIKE THIS: PROPOSED STATEWIDE "Shall the following Amendments be AMENDMENT NUMBER FOUR (4) adopted to the Constitution of Alabama?" Relating to Blount County, proposing an PROPOSED AMENDMENTS WHICH amendment to the Constitution of Alabama FOR ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE FOR PUBLIC SERVICE of 1901, to prohibit any municipality located APPLY TO THE STATE AT LARGE STRAIGHT PARTY VOTING SUPREME COURT, PLACE NO. 1 COMMISSION, PLACE NO. 1 entirely outside of Blount County from (Vote for One) (Vote for One) imposing any municipal ordinance or ALABAMA RHONDA CHAMBERS JAN COOK regulation, including, but not limited to any Democrat Democrat DEMOCRATIC PROPOSED STATEWIDE KELLI WISE TWINKLE ANDRESS CAVANAUGH THESE OFFICES WILL NOT RUN IN ALL PRECINCTS tax, zoning, planning, or sanitation PARTY Republican Republican AMENDMENT NUMBER ONE (1) regulations, and any inspection service in ALABAMA Write-in Write-in Proposing an amendment to the its police jurisdiction located in Blount REPUBLICAN Constitution of Alabama of 1901, to provide County and to provide that a municipality PARTY FOR ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE FOR PUBLIC SERVICE that the provision in Amendment 778, now prohibited from imposing any tax or SUPREME COURT, PLACE NO. 2 COMMISSION, PLACE NO. 2 appearing as Section 269.08 of the Official regulation under this amendment shall not FOR GOVERNOR (Vote for One) (Vote for One) provide any regulatory function or police or (Vote for One) Recompilation of the Constitution of TOM EDWARDS SUSAN PARKER Alabama of 1901, as amended, which fire protection services in its police Democrat Democrat jurisdiction located in Blount County, other RON SPARKS MICHAEL F. -

Open Mcgehrin Drew State of Faith.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES THE STATE OF FAITH: RELIGION AND RACE IN THE 1985 ALABAMA CASE OF WALLACE V. JAFFREE DREW MCGEHRIN Spring 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Religious Studies and History with interdisciplinary honors in Religious Studies and History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Anne C. Rose Distinguished Professor of History and Religious Studies Thesis Supervisor On-cho Ng Professor of History, Asian Studies, and Philosophy Honors Adviser in Religious Studies Michael Milligan Director of Undergraduate Studies Head of Undergraduate History Intern Program Senior Lecturer in History Second Reader and Honors Adviser in History * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the 1985 Supreme Court decision Wallace v. Jaffree. The case originated in a lawsuit against the State of Alabama by Ishmael Jaffree, an agnostic African American who challenged Governor George Wallace and two Alabama school prayer statutes. The first, enacted in 1981, instructed public schools to allocate time during the school day for a moment of silence for “voluntary prayer.” The second, passed in 1982, instructed teachers to lead their classes in a specific prayer approved by the Alabama State Legislature. Jaffree argued that these laws violated the First Amendment rights of his children, who were students in the Mobile public school system. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court declared the Alabama statutes unconstitutional under the Establishment Clause. The Court rejected Wallace’s states’ rights argument against the incorporation of the First Amendment. -

The Gubernatorial Elections of 2015: Hard-Fought Races for the Open Seats by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The Gubernatorial Elections of 2015: Hard-Fought Races for the Open Seats By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle Only three governors were elected in 2015. Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi are the only states that hold their gubernatorial elections during the year prior to the presidential election. This means that these three states can be early indicators of any voter unrest that might unleash itself more broadly in the next year’s congressional and presidential elections, and we saw some of this in the two races where candidates were vying for open seats. Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant (R) was elected to a second term, running in a state that strongly favored his political party. Both Kentucky and Louisiana have elected Democrats and Republicans to the governorship in recent years, and each race was seen as up for grabs by many political pundits. In the end, each election resulted in the governorship turning over to the other political party. Though Tea Party sentiments played a signifi- he lost badly to McConnell, he had name recog- cant role in the primary elections in Kentucky and nition when he entered the gubernatorial race as Louisiana, none of the general elections reflected an anti-establishment candidate who ran an out- the vigor that the Tea Party displayed in the 2014 sider’s campaign against two Republicans who had gubernatorial elections. With only two open races held elected office. Bevin funded the vast majority and one safe incumbent on the ballot, the 2015 of his primary spending himself, contributing more elections were generally not characterized as a than $2.4 million to his own campaign. -

Download2006 Primary Election Results by Precinct Cumulative by Offices and Amendments

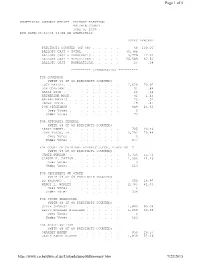

Page 1 of 5 UNOFFICIAL SUMMARY REPORT PRIMARY ELECTION BALDWIN COUNTY JUNE 6, 2006 RUN DATE:06/13/06 03:28 PM STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 69) . 69 100.00 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 30,388 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 3,776 12.43 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 26,589 87.50 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 23 .08 ********** (DEMOCRATIC) ********** FOR GOVERNOR (WITH 69 OF 69 PRECINCTS COUNTED) LUCY BAXLEY. 2,626 70.92 JOE COPELAND . 31 .84 HARRY LYON . 20 .54 KATHERINE MACK. 42 1.13 NATHAN MATHIS . 20 .54 JAMES POTTS. 15 .41 DON SIEGELMAN . 949 25.63 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 73 FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL (WITH 69 OF 69 PRECINCTS COUNTED) LARRY DARBY. 705 20.16 JOHN TYSON, JR. 2,792 79.84 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 277 FOR COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS JUDGE, PLACE NO. 2 (WITH 69 OF 69 PRECINCTS COUNTED) JAMIE DURHAM . 1,756 55.71 CLAUDE E. PATTON . 1,396 44.29 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 623 FOR SECRETARY OF STATE (WITH 69 OF 69 PRECINCTS COUNTED) ED PACKARD . 652 18.97 NANCY L. WORLEY . 2,785 81.03 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 338 FOR STATE TREASURER (WITH 69 OF 69 PRECINCTS COUNTED) STEVE SEGREST . 1,892 60.04 KEITH DOUGLAS WILLIAMS . 1,259 39.96 Over Votes . 0 Under Votes . 623 FOR STATE AUDITOR (WITH 69 OF 69 PRECINCTS COUNTED) CHARLEY BAKER . 859 26.57 JANIE BAKER CLARKE . 1,848 57.16 http://www.co.baldwin.al.us/Uploads/june06Summary.htm 7/22/2015 Page 2 of 5 WAYNE SOWELL . 526 16.27 Over Votes . -

2017 Official General Election Results

STATE OF ALABAMA Canvass of Results for the Special General Election held on December 12, 2017 Pursuant to Chapter 12 of Title 17 of the Code of Alabama, 1975, we, the undersigned, hereby certify that the results of the Special General Election for the office of United States Senator and for proposed constitutional amendments held in Alabama on Tuesday, December 12, 2017, were opened and counted by us and that the results so tabulated are recorded on the following pages with an appendix, organized by county, recording the write-in votes cast as certified by each applicable county for the office of United States Senator. In Testimony Whereby, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the Great and Principal Seal of the State of Alabama at the State Capitol, in the City of Montgomery, on this the 28th day of December,· the year 2017. Steve Marshall Attorney General John Merrill °\ Secretary of State Special General Election Results December 12, 2017 U.S. Senate Geneva Amendment Lamar, Amendment #1 Lamar, Amendment #2 (Act 2017-313) (Act 2017-334) (Act 2017-339) Doug Jones (D) Roy Moore (R) Write-In Yes No Yes No Yes No Total 673,896 651,972 22,852 3,290 3,146 2,116 1,052 843 2,388 Autauga 5,615 8,762 253 Baldwin 22,261 38,566 1,703 Barbour 3,716 2,702 41 Bibb 1,567 3,599 66 Blount 2,408 11,631 180 Bullock 2,715 656 7 Butler 2,915 2,758 41 Calhoun 12,331 15,238 429 Chambers 4,257 3,312 67 Cherokee 1,529 4,006 109 Chilton 2,306 7,563 132 Choctaw 2,277 1,949 17 Clarke 4,363 3,995 43 Clay 990 2,589 19 Cleburne 600 2,468 30 Coffee 3,730 8,063 -

The Republican Emergence in the Suburbs of Birmingham Alabama

A DEEP SOUTH SUBURB: THE REPUBLICAN EMERGENCE IN THE SUBURBS OF BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA By Ben Robbins A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the Department of History Mississippi State, Mississippi May 2009 Copyright by Ben Robbins 2009 A DEEP SOUTH SUBURB: THE REPUBLICAN EMERGENCE IN THE SUBURBS OF BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA By Ben Robbins Approved: ____________________________ _____________________________ Jason Phillips Alan Marcus Assistant Professor of History Professor of History, and (Director of Thesis) Head of the History Department ____________________________ ______________________________ Richard Damms Mary Katherine Barbier Associate Professor of History Assistant Professor of History (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ____________________________ Gary L. Meyers Interim Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences Name: Ben Robbins Date of Degree: May 2, 2009 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: History Major Advisor: Dr. Jason Phillips Title of Study: A DEEP SOUTH SUBURB: THE REPUBLICAN EMERGENCE IN THE SUBURBS OF BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA Pages in study: 108 Candidate for Degree of Master of Arts In 1952, affluent white suburban citizens of Birmingham, Alabama voted overwhelmingly in support of Dwight D. Eisenhower. This thesis explores and examines why the emergence of a thriving suburban community that voted Republican occurred. This examination used a collection of numerous sources, primary and secondary. Newspapers served as the most important tool for discovering why the new suburbs aligned to Republicanism. The sources describe a suburban area that aligned with the Republican Party due to numerous reasons: race, Eisenhower’s popularity, the Cold War, and economic issues. -

ALABAMA REPUBLICAN P ARTY

ALABAMA REPUBLICAN pARTY 3505 Lorna Road Birminqham, AL 35216 * P: 205-212-5900 * F: 205-212-591 0 March 21, 2018 The Honorable John Merrill Office of the Secretary of State State Capitol Suite E-208 Montgomery, AL 36130 Dear Secretary Merrill: Attached is the amended version of the certification letter that was submitted to you on March 14, 2018. There are two amendments listed below - one candidate removal and a name alteration. Below is the name that has been removed from the previous version. Office Circuit or District / Place # Candidate Name State Executive Committee Member Madison County, At Large, Place 3 Mary Scott Hunter Candidate name, Bryan A Murphy, for Alabama House of Representatives, District 38 has been changed to "Bryan Murphy" in the attached amended certification letter. This certificate is subject to such disqualifications or corrective action as hereafter may be made. Given under my hand, the twenty-first day of March, 2018. Terry Lathan Chairman Alabama Republican Party I,' Paid for and authorized by The Alabama Republican Party. -Not authorized by any candidate or candidate committee. ALABAMA REPUBLICAN pARTY 3505 Lorna Road Birmingham, AL 35216 * P: 205-212-5900 * F: 205-212-591 0 March 21, 2018 The Honorable John Merrill Office of the Secretary of State State Capitol Suite E-208 Montgomery, AL 36130 Dear Secretary Merrill: The Alabama Republican Party hereby certifies that the persons whose names appear below have qualified to run in the 2018 Alabama Republican Primary Election to be held on Tuesday, June 5,