Update of Future Containerships Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

No. 21264 MULTILATERAL International Convention on tonnage measurement of ships, 1969 (with annexes, official translations of the Convention in the Russian and Spanish languages and Final Act of the Conference). Concluded at London on 23 June 1969 Authentic texts: English and French. Authentic texts of the Final Act: English, French, Russian and Spanish. Registered by the International Maritime Organization on 28 September 1982. MULTILAT RAL Convention internationale de 1969 sur le jaugeage des navires (avec annexes, traductions officielles de la Convention en russe et en espagnol et Acte final de la Conf rence). Conclue Londres le 23 juin 1969 Textes authentiques : anglais et fran ais. Textes authentiques de l©Acte final: anglais, fran ais, russe et espagnol. Enregistr e par l©Organisation maritime internationale le 28 septembre 1982. Vol. 1291, 1-21264 4_____ United Nations — Treaty Series Nations Unies — Recueil des TVait s 1982 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION © ON TONNAGE MEASURE MENT OF SHIPS, 1969 The Contracting Governments, Desiring to establish uniform principles and rules with respect to the determination of tonnage of ships engaged on international voyages; Considering that this end may best be achieved by the conclusion of a Convention; Have agreed as follows: Article 1. GENERAL OBLIGATION UNDER THE CONVENTION The Contracting Governments undertake to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention and the annexes hereto which shall constitute an integral part of the present Convention. Every reference to the present Convention constitutes at the same time a reference to the annexes. Article 2. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of the present Convention, unless expressly provided otherwise: (1) "Regulations" means the Regulations annexed to the present Convention; (2) "Administration" means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is flying; (3) "International voyage" means a sea voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. -

Chapter 17. Shipping Contributors: Alan Simcock (Lead Member)

Chapter 17. Shipping Contributors: Alan Simcock (Lead member) and Osman Keh Kamara (Co-Lead member) 1. Introduction For at least the past 4,000 years, shipping has been fundamental to the development of civilization. On the sea or by inland waterways, it has provided the dominant way of moving large quantities of goods, and it continues to do so over long distances. From at least as early as 2000 BCE, the spice routes through the Indian Ocean and its adjacent seas provided not merely for the first long-distance trading, but also for the transport of ideas and beliefs. From 1000 BCE to the 13th century CE, the Polynesian voyages across the Pacific completed human settlement of the globe. From the 15th century, the development of trade routes across and between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans transformed the world. The introduction of the steamship in the early 19th century produced an increase of several orders of magnitude in the amount of world trade, and started the process of globalization. The demands of the shipping trade generated modern business methods from insurance to international finance, led to advances in mechanical and civil engineering, and created new sciences to meet the needs of navigation. The last half-century has seen developments as significant as anything before in the history of shipping. Between 1970 and 2012, seaborne carriage of oil and gas nearly doubled (98 per cent), that of general cargo quadrupled (411 per cent), and that of grain and minerals nearly quintupled (495 per cent) (UNCTAD, 2013). Conventionally, around 90 per cent of international trade by volume is said to be carried by sea (IMO, 2012), but one study suggests that the true figure in 2006 was more likely around 75 per cent in terms of tons carried and 59 per cent by value (Mandryk, 2009). -

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

Page 1 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. file://C:\Documents and Settings\M.Ventura\Local Settings\Temp\~hh4CFD.htm 2009-09-22 Page 2 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 - Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. -

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding A promising rst half, an uncertain second one 2018 started briskly in the wake of 2017. In the rst half of the year, newbuilding orders were placed at a rate of about 10m dwt per month. However the pace dropped in the second half, as owners grappled with a rise in newbuilding prices and growing uncertainty over the IMO 2020 deadline. Regardless, newbuilding orders rose to 95.5m dwt in 2018 versus 83.1m dwt in 2017. Demand for bulkers, container carriers and specialised ships increased, while for tankers it receded, re ecting low freight rates and poor sentiment. Thanks to this additional demand, shipbuilders succeeded in raising newbuilding prices by about 10%. This enabled them to pass on some of the additional building costs resulting from higher steel prices, new regulations and increased pressure from marine suppliers, who have also been struggling since 2008. VIIKKI LNG-fuelled forest product carrier, 25,600 dwt (B.Delta 25), built in 2018 by China’s Jinling for Finland’s ESL Shipping. 5 Orders Million dwt 300 250 200 150 100 50 SHIPBUILDING SHIPBUILDING KEY POINTS OF 2018 KEY POINTS OF 2018 0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Deliveries vs demolitions Fleet evolution Deliveries Demolitions Fleet KEY POINTS OF 2018 Summary 2017 2018 Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Ships 1,000 1,245 Orders 200 2,000 m dwt 83.1 95.5 180 The three Asian shipbuilding giants, representing almost 95% of the global 1,800 orderbook by deadweight, continued to ght ercely for market share. -

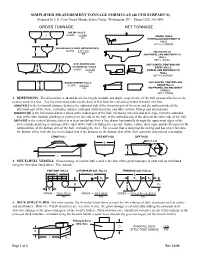

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, Washington, DC Phone (202) 366-6441 GROSS TONNAGE NET TONNAGE SAILING HULLS D GROSS = 0.5 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = 0.9 GROSS SAILING HULLS (KEEL INCLUDED IN D) D GROSS = 0.375 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS SHIP-SHAPED AND SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND CYLINDRICAL HULLS D D BARGE HULLS GROSS = 0.67 LBD (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN 100 HULL) NET = 0.8 GROSS BARGE-SHAPED HULLS SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND D GROSS = 0.84 LBD BARGE HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS 1. DIMENSIONS. The dimensions, L, B and D, are the length, breadth and depth, respectively, of the hull measured in feet to the nearest tenth of a foot. See the conversion table on the back of this form for converting inches to tenths of a foot. LENGTH (L) is the horizontal distance between the outboard side of the foremost part of the stem and the outboard side of the aftermost part of the stern, excluding rudders, outboard motor brackets, and other similar fittings and attachments. BREADTH (B) is the horizontal distance taken at the widest part of the hull, excluding rub rails and deck caps, from the outboard side of the skin (outside planking or plating) on one side of the hull, to the outboard side of the skin on the other side of the hull. DEPTH (D) is the vertical distance taken at or near amidships from a line drawn horizontally through the uppermost edges of the skin (outside planking or plating) at the sides of the hull (excluding the cap rail, trunks, cabins, deck caps, and deckhouses) to the outboard face of the bottom skin of the hull, excluding the keel. -

Ship Design Decision Support for a Carbon Dioxide Constrained Future

Ship Design Decision Support for a Carbon Dioxide Constrained Future John Nicholas Calleya A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University College London. Department of Mechanical Engineering University College London 2014 2 I, John Calleya confirm that that the work submitted in this Thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated in the Thesis. Abstract The future may herald higher energy prices and greater regulation of shipping’s greenhouse gas emissions. Especially with the introduction of the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), tools are needed to assist engineers in selecting the best solutions to meet evolving requirements for reducing fuel consumption and associated carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. To that end, a concept design tool, the Ship Impact Model (SIM), for quickly calculating the technical performance of a ship with different CO2 reducing technologies at an early design stage has been developed. The basis for this model is the calculation of changes from a known baseline ship and the consideration of profitability as the main incentive for ship owners or operators to invest in technologies that reduce CO2 emissions. The model and its interface with different technologies (including different energy sources) is flexible to different technology options; having been developed alongside technology reviews and design studies carried out by the partners in two different projects, “Low Carbon Shipping - A Systems Approach” majority funded by the RCUK energy programme and “Energy Technology Institute Heavy Duty Vehicle Efficiency - Marine” led by Rolls-Royce. -

Determirjiation of the Compensated Gross Tonnage Factors for Superyachts

International Shipbuilding Progress 57 (2010) 127-146 127 DOI 10.3233/ISP-2010-0066 lOS Press Determirjiation of the Compensated Gross Tonnage factors for superyachts Jeroen FJ. Pruyn Robert G. Helckenberg ^ and Chris M. van Hooren^ ^ Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands ^ Supeiyacht Builders Association, Delft, The Netherlands In order to provide the basis for a fair comparison, an indicator was developed to measure the amount of work that goes into the construction of a vessel. The foundation for this Compensated Gross Tonnage was laid in the 1970s by the OECD to compensate for the differences in work involved in producing a gross ton (GT) of ship in different sizes and types. Since 2007, the CGT of a vessel of a certain type as a function of its size (measured in GT) has been expressed as CGT = A x GT-®. However, no interna tionally accepted A and B values exist to convert superyachts from GT to CGT. The superyacht building industry believes that this omission results in an under appreciation of the importance of the sector. This paper describes the research carried out into this subject and confirms that the cuiTent assignments for su peryachts greatly under appreciate the value of the sector. Based on the current data, the most appropriate values for superyachts are 278 for A and 0.58 for B. The spread is quite large and more data would help confirm this finding. Keywords: CGT, superyachts, shipbuilding 1. Background: CGT factors To compare the output of shipyards and shipbuilding industries using the size of delivered vessels (e.g., in terms of Gross Tonnage) alone is insufficient: how does one compare a (very large) crude oil tanker to a (smaller but much more complex) passenger ship? In order to provide the foundation for a fair comparison, an indicator was de veloped to measure the amount of work that goes into the construction of a ves sel: Compensated Gross Tonnage. -

Measurement of Fishing

35 Rapp. P.-v. Réun. Cons. int. Explor. Mer, 168: 35-38. Janvier 1975. TONNAGE CERTIFICATE DATA AS FISHING POWER PARAMETERS F. d e B e e r Netherlands Institute for Fishery Investigations, IJmuiden, Netherlands INTRODUCTION London, June 1969 — An entirely new system of The international exchange of information about measuring the gross and net fishing vessels and the increasing scientific approach tonnage was set up called the to fisheries in general requires the use of a number of “International Convention on parameters of which there is a great variety especially Tonnage Measurement of in the field of main dimensions, coefficients, propulsion Ships, 1969” .1 data (horse power, propeller, etc.) and other partic ulars of fishing vessels. This variety is very often caused Every ship which has been measured and marked by different historical developments in different in accordance with the Convention concluded in Oslo, countries. 1947, is issued with a tonnage certificate called the The tonnage certificate is often used as an easy and “International Tonnage Certificate”. The tonnage of official source for parameters. However, though this a vessel consists of its gross tonnage and net tonnage. certificate is an official one and is based on Inter In this paper only the gross tonnage is discussed national Conventions its value for scientific purposes because net tonnage is not often used as a parameter. is questionable. The gross tonnage of a vessel, expressed in cubic meters and register tons (of 2-83 m3), is defined as the sum of all the enclosed spaces. INTERNATIONAL REGULATIONS ON TONNAGE These are: MEASUREMENT space below tonnage deck trunks International procedures for measuring the tonnage tweendeck space round houses of ships were laid down as follows : enclosed forecastle excess of hatchways bridge spaces spaces above the upper- Geneva, June 1939 - International regulations for break(s) deck included as part of tonnage measurement of ships poop the propelling machinery were issued through the League space. -

Journal of KONES 2013 NO 2 VOL 20

Journal of KONES Powertrain and Transport, Vol. 20, No. 2013 DIMENSIONAL CONSTRAINTS IN SHIP DESIGN Adam Charchalis Gdynia Maritime University Faculty of Marine Engineering Morska Street 83, 81-225 Gdynia, Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The paper presents general rules for calculations of ship’s hull principle dimensions at preliminary stage of design process. There are characterized and defined basic assumptions of design process and limitations for calculations of dimensions and some criteria numbers. Limitations are an outcome of shipping routes what is related to shipping restrictions, diminishing of hull drag, achieving of required strength of hull and safety of shipping requirements. Shipping limitations are because of canals and straits dimensions or harbours drafts. In order to diminish propulsion power, what is related to economically justified solution, selected form and dimensions of hull must ensure minimizing of resistance, including skin friction and wavemaking resistance. That is why proper selection of coefficients of hull shape and dimensional criteria according to ship owner’s requirements i.e. deadweight (DWT) or cargo capacity (TEU), speed and seakeeping. In the paper are analyzed dimensional constraints due to shipping region, diminishing of wavemaking and skin friction resistance or application of Froude Number, ships dimensional coefficients (block coefficient, L/B, B/T, L/H) and coefficients expressing relations between capacity and displacement. The scope of applicability above presented values for different modern vessels construction were analyzed. Keywords: ship principal dimensions, hull volumetric coefficients, hull design 1. Methodology of ship’s principal dimensions selection at early design stage Process of ship design consist of several subsequent stages. -

Branch's Elements of Shipping/Alan E

‘I would strongly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in shipping or taking a course where shipping is an important element, for example, chartering and broking, maritime transport, exporting and importing, ship management, and international trade. Using an approach of simple analysis and pragmatism, the book provides clear explanations of the basic elements of ship operations and commercial, legal, economic, technical, managerial, logistical, and financial aspects of shipping.’ Dr Jiangang Fei, National Centre for Ports & Shipping, Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Australia ‘Branch’s Elements of Shipping provides the reader with the best all-round examination of the many elements of the international shipping industry. This edition serves as a fitting tribute to Alan Branch and is an essential text for anyone with an interest in global shipping.’ David Adkins, Lecturer in International Procurement and Supply Chain Management, Plymouth Graduate School of Management, Plymouth University ‘Combining the traditional with the modern is as much a challenge as illuminating operations without getting lost in the fascination of the technical detail. This is particularly true for the world of shipping! Branch’s Elements of Shipping is an ongoing example for mastering these challenges. With its clear maritime focus it provides a very comprehensive knowledge base for relevant terms and details and it is a useful source of expertise for students and practitioners in the field.’ Günter Prockl, Associate Professor, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark This page intentionally left blank Branch’s Elements of Shipping Since it was first published in 1964, Elements of Shipping has become established as a market leader. -

Analysis of Fires and Firefighting Operations on Fully Cellular Container Vessels Over the Period 2000 – 2015

Analysis of fires and firefighting operations on fully cellular container vessels over the period 2000 – 2015 Diploma dissertation for the award of the academic degree "Diplom-Wirtschaftsingenieur für Seeverkehr (FH)" (BSc equivalent in marine industrial engineering) in the Summer semester of 2016 submitted to Bremen University of Applied Sciences – Faculty 5 "Nature and Engineering" on the study course "Diplom-Wirtschaftsingenieur für Seeverkehr" (nautical science) Examined by: Professor Captain Thomas Jung Co-examiner: Captain Ute Hannemann Submitted by: Helge Rath, Neustadtswall 14, 28199 Bremen, Germany Phone: 0170-5582269 Email: [email protected] Student registration no.: 355621 Date: Thursday, September 01, 2016 Foreword I Foreword I remember walking with my grandfather by the locks of the Kiel Canal in Brunsbüttel as a small child and marveling at the ships there. Thanks to his many years working as an electrician on the locks, my grandfather was able to tell me a lot about the ships that passed through. And it was these early impressions that first awakened my interest in shipping. Having completed a "vacation internship" at the age of 17 at the shipping company Leonhardt & Blumberg (Hamburg), I decided to train as a ship's mechanic. A year later, I started training at the Hamburg-based shipping company Claus-Peter Offen and qualified after 2 ½ years. I then worked for 18 months as a ship's mechanic on the jack-up vessel THOR, operated by Hochtief Solutions AG, which gave me the opportunity to gain a wealth of experience in all things nautical. While studying for my degree in nautical science at the Bremen University of Applied Sciences, I spent the semester breaks on two different fully cellular container vessels owned by the shipping company Claus-Peter Offen to further my knowledge as a ship's engineer and prospective nautical engineer. -

Port Developments

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2012 Report by the UNCTAD secretariat Chapter 4 UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2012 PORT DEVELOPMENTS :RUOGFRQWDLQHUSRUWWKURXJKSXWLQFUHDVHGE\DQHVWLPDWHG}SHUFHQWWR}PLOOLRQ IRRWHTXLYDOHQWXQLWV 7(8V LQLWVKLJKHVWOHYHOHYHU7KLVLQFUHDVHZDVORZHU WKDQWKH}SHUFHQWLQFUHDVHRIWKDWZDVLWVHOIDVKDUSUHERXQGIURPWKHVOXPS of 2009. Chinese mainland ports maintained their share of total world container port WKURXJKSXWDW}SHUFHQW 7KH81&7$'/LQHU6KLSSLQJ&RQQHFWLYLW\,QGH[ /6&, VKRZHGDFRQWLQXDWLRQLQ of the trend towards larger ships deployed by a smaller number of companies. Between 2011 and 2012, the number of companies providing services per country went down E\ } SHU FHQW ZKLOH WKH DYHUDJH VL]H RI WKH ODUJHVW FRQWDLQHU VKLSV LQFUHDVHG E\ }SHUFHQW2QO\}SHUFHQWRIFRXQWU\SDLUVDUHVHUYHGE\GLUHFWOLQHUVKLSSLQJ connections; for the remaining country pairs at least one trans-shipment port is required. This chapter covers container port throughput, liner shipping connectivity and some of WKHPDMRUSRUWGHYHORSPHQWSURMHFWVXQGHUZD\LQGHYHORSLQJFRXQWULHV,WDOVRDVVHVVHV how recent trends in ship enlargement may impact ports. 80 REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2012 A. PORT THROUGHPUT HFRQRPLHV IRU LV HVWLPDWHG DW } SHU FHQW signifying a return to previous year-on-year growth Port throughput is usually measured in tons and by levels. Developing economies’ share of world FDUJR W\SH IRU H[DPSOH OLTXLG RU GU\ FDUJR /LTXLG throughput continues to remain virtually unchanged at cargo is usually measured in tons