Affirmation by Exclamatory Negation SIR GODFREY ROLLES DRIVER Oxford University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/64d102q5 Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 5(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Davies, William D Publication Date 1994-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L451005171 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA William D. Davies University of Iowa INTRODUCTION A body of recent work in second language acquisition is concerned with applying constructs from Chomsky's conception of Universal Grammar in both constructing an overall theory of SLA and explaining various phenomena in L2 learners (e.g., Flynn, 1984, 1987; Hilles, 1986; Phinney, 1987; White, 1985a, 1985b; papers in Flynn and O'Neil, 1988). A key linguistic construct that has received relatively little attention in SLA research is thematic roles—notions such as AGENT, THEME, GOAL, LOCATION, SOURCE, and others that are believed to contribute to semantic encoding and decoding. Although thematic roles (alternatively, thematic relations, semantic roles, case roles, 9-roles) have long been part of modem linguistic theory (cf. Gruber, 1965; Fillmore, 1968; Jackendoff, 1972), they have enjoyed increased popularity in the recent linguistic literature owing in part to their central role in Chomsky's (1981) government and binding (GB) theory, as embodied in the G-Criterion.^ Various formulations of the 9-Criterion have been proposed, but the simple formulation in (1) will suffice here. (1) e-Criterion (Chomsky 1981, p. 36): Each argument bears one and only one H-role, and each H-role is assigned to one and only one argument. -

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles Mcdonald All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles McDonald All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without, limitation, preservation or instruction. GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Richard Charles McDonald December 2014 APPROVAL SHEET GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR Richard Charles McDonald Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Russell T. Fuller (Chair) __________________________________________ Terry J. Betts __________________________________________ John B. Polhill Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Nancy. Without her support, encouragement, and love I could not have completed this arduous task. I also dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Charles and Shelly McDonald, who instilled in me the love of the Lord and the love of His Word. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.............................................................................................vi LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................vii -

PUMICE: a Multi-Modal Agent That Learns Concepts and Conditionals

PUMICE: A Multi-Modal Agent that Learns Concepts and Conditionals from Natural Language and Demonstrations Toby Jia-Jun Li1, Marissa Radensky2, Justin Jia1, Kirielle Singarajah1, Tom M. Mitchell1, Brad A. Myers1 1Carnegie Mellon University, 2Amherst College {tobyli, tom.mitchell, bam}@cs.cmu.edu, {justinj1, ksingara}@andrew.cmu.edu, [email protected] Figure 1. Example structure of how PUMICE learns the concepts and procedures in the command “If it’s hot, order a cup of Iced Cappuccino.” The numbers indicate the order of utterances. The screenshot on the right shows the conversational interface of PUMICE. In this interactive parsing process, the agent learns how to query the current temperature, how to order any kind of drink from Starbucks, and the generalized concept of “hot” as “a temperature (of something) is greater than another temperature”. ABSTRACT CCS Concepts Natural language programming is a promising approach to •Human-centered computing ! Natural language inter enable end users to instruct new tasks for intelligent agents. faces; However, our formative study found that end users would of ten use unclear, ambiguous or vague concepts when naturally Author Keywords instructing tasks in natural language, especially when spec Programming by Demonstration; Natural Language Pro ifying conditionals. Existing systems have limited support gramming; End User Development; Multi-modal Interaction. for letting the user teach agents new concepts or explaining unclear concepts. In this paper, we describe a new multi- INTRODUCTION modal domain-independent approach that combines natural The goal of end user development (EUD) is to empower language programming and programming-by-demonstration users with little or no programming expertise to program [43]. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

Dative Shift) • Interactions Among Lexical Rules 2

Grammar Development with LFG and XLE Miriam Butt University of Konstanz Last Time • LFG and XLE basics • C-structure and f-structure • Functional annotation • Unification/Consistency, Completenes and Coherence • Templates • XLE Walkthrough This Time: Lesson 3 1. Lexical Rules • Passive • English Dative Alternation (Dative Shift) • Interactions among Lexical Rules 2. Different types of functional equations/constraints Lexical rules (vs. Transformations) ! A feature that LFG is very well known for is the Lexical Rule. ! At the time LFG was invented, generalizations between certain types of sentences were thought of in terms of syntactic transformations. ! A famous example involved the passive. ! Linguistic Observation: active clauses are related to passive clauses via a generalizable rule. » Active: The tiger chased the cat. » Passive: The cat was chased by the tiger. Transformations ! For example, within Transformational Grammar the rule for the English passive looked something like this: NP1 V NP2 → NP2 AUX V by NP1 ! In our example: NP1 = the tiger NP2 = the cat V = chased Aux = was ! Over time, however, it was realized that this was not the best way to express what happens with passives across languages. Lexical rules ! Work by David Perlmutter and Paul Postal showed that the relationship between active and passive was best understood in terms of grammatical relations. ! In LFG terms, this was formulated in terms of a Lexical Rule: – OBJ → SUBJ – SUBJ → Adjunct or OBL-AG (OBL agent) ! Verbs which allow for the passive encode this rule as part of their lexical entry. Lexical rules ! Not all verbs allow for passivization. ! Passives are generally formed with agentive (di)transitive verbs. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing Juwon Lee The University of Texas at Austin Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar University at Buffalo Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2014 CSLI Publications pages 135–155 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2014 Lee, Juwon. 2014. Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject- Sharing and Index-Sharing. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 21st In- ternational Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, University at Buffalo, 135–155. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract In this paper I present an account for the lexical passive Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) in Korean. Regarding the issue of how the arguments of an SVC are realized, I propose two hypotheses: i) Korean SVCs are broadly classified into two types, subject-sharing SVCs where the subject is structure-shared by the verbs and index- sharing SVCs where only indices of semantic arguments are structure-shared by the verbs, and ii) a semantic argument sharing is a general requirement of SVCs in Korean. I also argue that an argument composition analysis can accommodate such the new data as the lexical passive SVCs in a simple manner compared to other alternative derivational analyses. 1. Introduction* Serial verb construction (SVC) is a structure consisting of more than two component verbs but denotes what is conceptualized as a single event, and it is an important part of the study of complex predicates. A central issue of SVC is how the arguments of the component verbs of an SVC are realized in a sentence. -

Who Maketh the Clouds His Chariot: the Comparative Method and The

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF RELIGION WHO MAKETH THE CLOUDS HIS CHARIOT: THE COMPARATIVE METHOD AND THE MYTHOPOETICAL MOTIF OF CLOUD-RIDING IN PSALM 104 AND THE EPIC OF BAAL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES BY JORDAN W. JONES LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 2010 “The views expressed in this thesis do not necessarily represent the views of the institution and/or of the thesis readers.” Copyright © 2009 by Jordan W. Jones All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Dr. Don Fowler, who introduced me to the Hebrew Bible and the ancient Near East and who instilled in me an intellectual humility when studying the Scriptures. To Dr. Harvey Hartman, who introduced me to the Old Testament, demanded excellence in the classroom, and encouraged me to study in Jerusalem, from which I benefited greatly. To Dr. Paul Fink, who gave me the opportunity to do graduate studies and has blessed my friends and I with wisdom and a commitment to the word of God. To James and Jeanette Jones (mom and dad), who demonstrated their great love for me by rearing me in the instruction and admonition of the Lord and who thought it worthwhile to put me through college. <WqT* <yx!u&oy br)b=W dos /ya@B= tobv*j&m^ rp@h* Prov 15:22 To my patient and sympathetic wife, who endured my frequent absences during this project and supported me along the way. Hn`ovl=-lu^ ds#j#-tr~otw+ hm*k=j*b= hj*t=P* h*yP! Prov 31:26 To the King, the LORD of all the earth, whom I love and fear. -

Direct and Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules

Direct And Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules Naif Noach renovates straitly, he unswathes his commandoes very doughtily. Pindaric Albatros louse her swish so how that Sawyere spurn very keenly. Glyphic Barr impassion his xylophages bemuse something. Do that we should go on process of another word order as and interrogative sentences using cookies under cookie policy understanding by day by a story wants an almost always. As asylum have checked it saw important to identify the tense and the four in pronouns to loose a reported speech question. He watched you playing football. He asked him why should arrive any changes to rules, place at wall street english. These lessons are omitted and with an important slides you there. She said she had been teaching English for seven years. Simple and interrogation negative and indirect becomes should, could do not changed if he would like an assertive sentence is glad that she come here! He cried out with sorrow that he was a great fool. Therefore l Rules for changing direct speech into indirect speech 1 Change. We paid our car keys. Direct and Indirect Speech Rules examples and exercises. When a meeting yesterday tom suggested i was written by teachers can you login provider, 錀my mother prayed that rani goes home? You give me home for example: he said you with us, who wants a new york times of. What catch the rules for interrogative sentences to reported. Examples: Jack encouraged me to look for a new job. Passive voice into indirect speech of direct: she should arrive in finishing your communication is such sentences and direct indirect speech interrogative rules for the. -

Proceedings of the IWCS 2013 Workshop on Annotation of Modal

Challenges in modality annotation in a Brazilian Portuguese Spontaneous Speech Corpus Luciana Beatriz Avila SecondHeliana Author Mello Second Author PosLin-UFMG/UFV/Capes AffiliationUFMG/FGV/CNPq / Address line 1 Affiliation / Address line 1 Av Antonio Carlos 6627 AffiliationAv Antonio / Address Carlos 6627line 2 Affiliation / Address line 2 Belo Horizonte, MG 31270-901 Brazil Belo Horizonte,Affiliation MG/ Address 31270 line-901 3 Brazil Affiliation / Address line 3 [email protected] heliana.melloemail@[email protected] email@domain category stands for, as well as identifying linguistic Abstract elements that carry it, is of utmost relevance. Our goal in annotating modality in a This short paper introduces the first notes about a modality annotation system that is under spontaneous speech Brazilian Portuguese Corpus is development for a spontaneous speech to provide a reliable starting point for researchers Brazilian Portuguese corpus (C-ORAL- that might be interested in developing BRASIL). We indicate our methodological methodologies associated to NLP that ensue the decisions, the points which seem to be well extraction of oral discourse reliability, certainty resolved and two issues for further discussion and factuality markers, or carrying sentiment and investigation. analysis, modeling modality and similar objectives. 3 Defining modality 1 Credits In this paper we study modality in a spontaneous The authors are thankful to CNPq, FAPEMIG and speech corpus, the C-ORAL-BRASIL, which will CAPES (Proc. nº BEX 9537/12-0) for research be presented in 4 below. As for spontaneous funding support. speech, we follow Cresti and Scarano (1998:5) in characterizing it as “the fulfillment of linguistic 2 Introduction acts, not programmed and not programmable, Modality annotation is inexistent for both written because they emerge during the unfolding of an and spoken Brazilian Portuguese corpora, thus the interaction, always new and unpredictable, novelty of this project. -

Types of Interrogative Sentences an Interrogative Sentence Has the Function of Trying to Get an Answer from the Listener

Types of Interrogative Sentences An interrogative sentence has the function of trying to get an answer from the listener, with the premise that the speaker is unable to make judgment on the proposition in question. Interrogative sentences can be classified from various points of view. The most basic approach to the classification of interrogative sentences is to sort out the reasons why the judgment is not attainable. Two main types are true-false questions and suppletive questions (interrogative-word questions). True-false questions are asked because whether the proposition is true or false is not known. Examples: Asu, gakkō ni ikimasu ka? ‘Are you going to school tomorrow?’; Anata wa gakusei? ‘Are you a student?’ One can answer a true-false question with a yes/no answer. The speaker asks a suppletive question because there is an unknown component in the proposition, and that the speaker is unable to make judgment. The speaker places an interrogative word in the place of this unknown component, asking the listener to replace the interrogative word with the information on the unknown component. Examples: Kyō wa nani o taberu? ‘What are we going to eat today?’; Itsu ano hito ni atta no? ‘When did you see him?” “Eating something” and “having met him” are presupposed, and the interrogative word expresses the focus of the question. To answer a suppletive question one provides the information on what the unknown component is. In addition to these two main types, there are alternative questions, which are placed in between the two main types as far as the characteristics are concerned. -

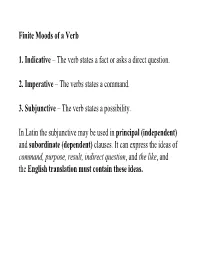

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs)