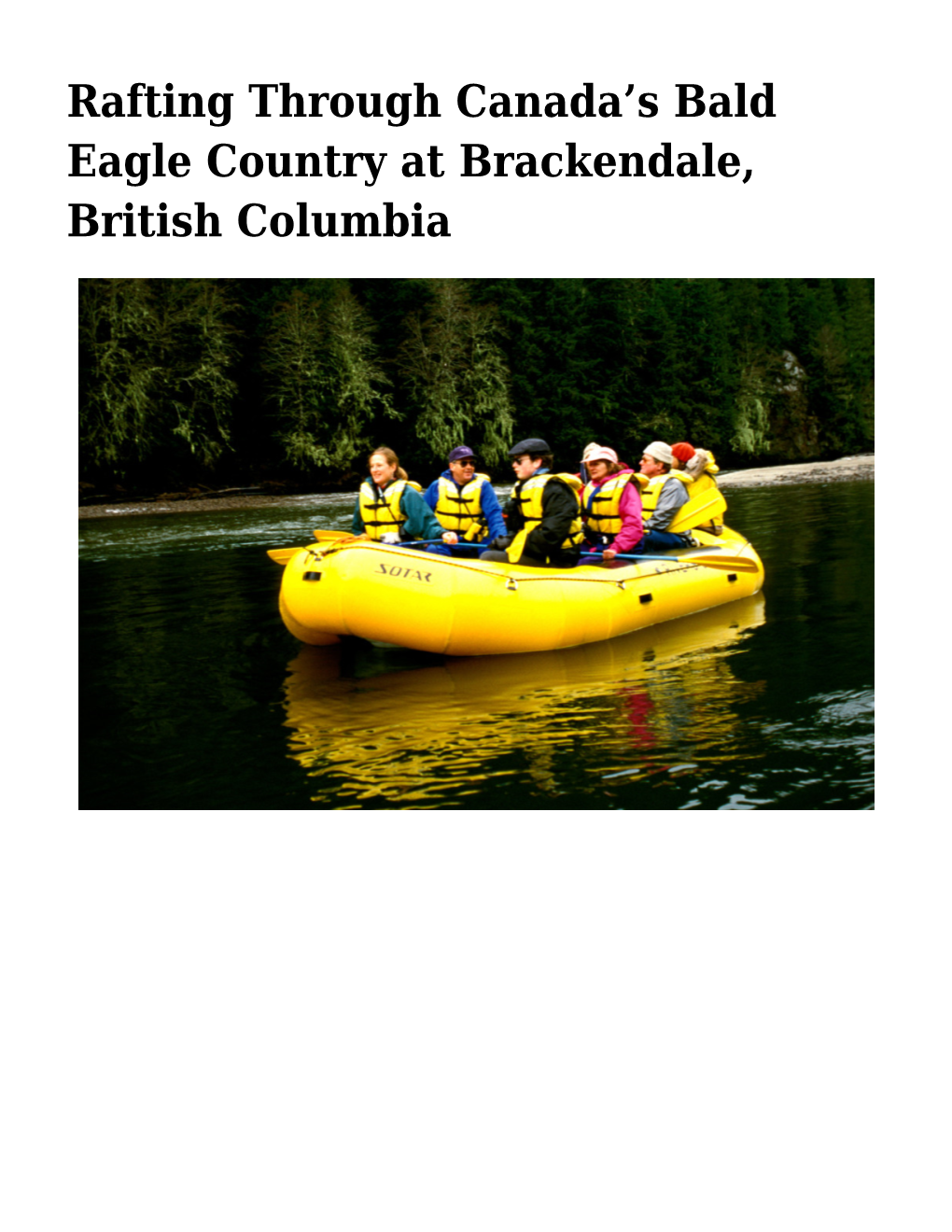

Rafting Through Canada’S Bald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garibaldi Provincial Park M ASTER LAN P

Garibaldi Provincial Park M ASTER LAN P Prepared by South Coast Region North Vancouver, B.C. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Garibaldi Provincial Park master plan On cover: Master plan for Garibaldi Provincial Park. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-7726-1208-0 1. Garibaldi Provincial Park (B.C.) 2. Parks – British Columbia – Planning. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Parks. South Coast Region. II Title: Master plan for Garibaldi Provincial Park. FC3815.G37G37 1990 33.78”30971131 C90-092256-7 F1089.G3G37 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS GARIBALDI PROVINCIAL PARK Page 1.0 PLAN HIGHLIGHTS 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION 2 2.1 Plan Purpose 2 2.2 Background Summary 3 3.0 ROLE OF THE PARK 4 3.1 Regional and Provincial Context 4 3.2 Conservation Role 6 3.3 Recreation Role 6 4.0 ZONING 8 5.0 NATURAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 11 5.1 Introduction 11 5.2 Natural Resources Management: Objectives/Policies/Actions 11 5.2.1 Land Management 11 5.2.2 Vegetation Management 15 5.2.3 Water Management 15 5.2.4 Visual Resource Management 16 5.2.5 Wildlife Management 16 5.2.6 Fish Management 17 5.3 Cultural Resources 17 6.0 VISITOR SERVICES 6.1 Introduction 18 6.2 Visitor Opportunities/Facilities 19 6.2.1 Hiking/Backpacking 19 6.2.2 Angling 20 6.2.3 Mountain Biking 20 6.2.4 Winter Recreation 21 6.2.5 Recreational Services 21 6.2.6 Outdoor Education 22 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISITOR SERVICES (Continued) Page 6.2.7 Other Activities 22 6.3 Management Services 22 6.3.1 Headquarters and Service Yards 22 6.3.2 Site and Facility Design Standards -

2010-08-17 Package Council COMPLETE

R EGULAR MEETING OF MUNICIPAL COUNCIL AGENDA TUESDAY, AUGUST 17, 2 0 1 0 , STARTING AT 5:30 PM In the Franz Wilhelmsen Theatre at Maurice Young Millennium Place 4335 Blackcomb Way, Whistler, BC V0N 1B4 APPROVAL OF AGENDA Approval of the Regular Council agenda of August 17, 2010. ADOPTION OF MINUTES Adoption of the Regular Council minutes of August 3, 2010. PUBLIC QUESTION AND ANSWER PERIOD PRESENTATIONS/DELEGATIONS Whistler Half Marathon A presentation by Dave Clark, Race Director, regarding the Whistler Half Marathon for June 2011. RBC GranFondo A presentation by Neil McKinnon, GranFondo Canada co-founder, regarding the RBC Gran Fondo for September 11, 2010. Pay Parking An update regarding pay parking by Bob MacPherson, General Manager of Community Life. BC Transit A presentation by Manuel Achadinha, CEO, Peter Rantucci, Director – Regional Transit Systems, and Johann van Schaik, Regional Transit Manager – South Coast, regarding Key Performance Indicators for BC Transit. MAYOR’S REPORT ADMINISTRATIVE REPORTS RBC GranFondo Whistler That Council endorses the Special Occasion License application of Fraser Boyer for the Special Occasion Liquor RBC GranFondo Whistler to be held on Saturday, September 11, 2010. License Report No. 10-081 File No. 7627.2 Regular Council Meeting Agenda August 17, 2010 Page 2 Whistler Aggregates That Council considers giving first reading to Official Community Plan Amendment Rezoning Bylaw (Material Extraction) No. 1931, 2009; Report No. 10-086 File No. RZ. 1025 That Council considers giving second reading to -

Cheakamus River – Balls to the Wall

Cheakamus River – Balls To The Wall Vitals Locale: Whistler, British Columbia What It's Like: Extension of the Upper Cheak - great class IV-IV+ river running, and a bonus waterfall. Some wood. Class: IV-IV+ Scouting/Portaging: Scouting is ok. Difficult to portage in spots, if you're forced to. Falls is easy to walk. Level: Online gauge: http://wateroffice.ec.gc.ca/report/report_e.html?type=realTime&stn=08GA072 Cheakamus River - this gauge is at the put in. Time: 2-3 hours for a relaxed first trip. When To Go: All season, very pushy at high flows. Reasonable minimum is 2.1. Info From: Many visits. Other Beta: None. Description Gauge info: if you have previous experience on the Cheak, note that the gauge changed sometime before the 2015 season and now reads about 0.1 m lower than it used to. Levels are adjusted appropriately on this page. The Cheakamus River is synonymous with Whistler kayaking, largely because of the ultra-classic Upper Cheak section near Function Junction. Unbeknownst to many and maybe avoided by others because of tales of epic log jams and the Whistler waste water treatment plant, there is an equally fun and perhaps more adventurous stretch that departs from the Upper Cheak take out and ends at the confluence with Callaghan Creek. It's a little bit harder, a little bit more committing, it has a great waterfall for those so inclined and there is a lot more wood in the river. You can run it as a stand-alone section of whitewater if you want something short, but it's best combined with the Upper Cheak to make a great hour or two of river running. -

CHEAKAMUS RIVER Coho Salmon Production from Constructed Off-Channel Habitat, 2001

LOWER MAINLAND BCH HABITAT RESTORATION 2000-2001 CHEAKAMUS RIVER Coho Salmon Production From Constructed Off-Channel Habitat, 2001 M. Foy, Biologist; H. Beardmore, Engineer; S. Gidora, Bio-technician Resource Restoration Group, Habitat and Enhancement Branch Lower Fraser Area, Pacific Region, Fisheries and Oceans Canada August, 2002 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………….……………...3 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………..3 2. STUDYAREA………………………………………………………….………………3 3. METHODS…………………………………………………………………………….4 3.1. Coho population estimate, off-channel habitat……………………4 3.1.1. Downstream weir counts………………………………………….4 3.1.2. Minnow trap mark-recapture estimate…………………………..5 3.1.3. Total coho production from constructed habitat………………..5 3.2. Coho population estimate, Cheakamus watershed………….…………….5 3.2.1. Marked population………………………………………………..5 3.2.2. Recovery of marked fish………………………………………….6 3.2.3. Coho production estimate, Cheakamus watershed……………..6 4. RESULTS……………………………………………………………….……………..6 4.1. Coho population estimate, off-channel habitat……………………6 4.1.1. Downstream weir counts………………………………………….6 4.1.2. Minnow trapping mark-recapture estimate……………………..7 4.1.3. Total coho production from constructed habitat………………..7 4.2. Coho population estimate, Cheakamus watershed………….…………….7 4.2.1. Marked population………………………………………………..7 4.2.2 Recovery of marked fish…………………………………………..7 4.2.3. Coho production, Cheakamus watershed……………………….7 5. DISCUSSION………………………………………………………………………….8 6. CONCLUSIONS………………………………………………………………………9 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………..9 -

The Mamquam River Floodplain Restoration Project

Background Information: The Mamquam River Floodplain Restoration Project The Mamquam River Floodplain Restoration project is being undertaken in The partnership with the Squamish River Watershed Society, Fisheries and Oceans Mamquam Canada, District of Squamish, and Squamish Nation. Funding support has been River is received from the Pacific Salmon Commission, B.C. Ministry of Transportation, important Pacific Salmon Foundation, Canadian Hydro Development Corporation. The coho and Squamish River Watershed Society and the local community are working closely Chinook to provide future working plans for conservation of these important floodplain salmon lands. habitat. 2005 The Mamquam River is an important coho, pink, chum and Chinook salmon producing tributary within the Squamish River watershed. The Squamish River estuary, lying at the head of Howe Sound, was formed at the confluences of the Mamquam and Squamish Rivers and historically supported a large complex wetland with interconnected tidally influenced sloughs and channels. These diverse habitats provided exceptional quality habitat for many salmonid species particularly coho, pink, chum and Chinook salmon. Dyking in the early twentieth century confined the Mamquam River and Squamish Rivers to relatively narrow corridors isolated from most of their historic floodplain The building lands. Internal drainages remain in some of the undeveloped portions of these of dykes on isolated floodplain areas but suffer from reduced flows and poor connections to the viable salmon populations in adjacent habitats. One such drainage is Loggers Lane Mamquam & Creek. Loggers Lane Creek was originally a river channel of the Mamquam River Squamish but was isolated following a giant storm in 1921 after which the dyke was built. -

Cheakamus River Watershed Action Plan

CHEAKAMUS RIVER WATERSHED ACTION PLAN FINAL November 14, 2017 Administrative Update July 21, 2020 The Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program is a partnership between BC Hydro, the Province of B.C., Fisheries and Oceans Canada, First Nations and Public Stakeholders to conserve and enhance fish and wildlife impacted by BC Hydro dams. The Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program is conserving and enhancing fish and wildlife impacted by BC Hydro dam construction in this watershed. Top row from left: Cheakamus Dam and powerhouse. Bottom row from left: Squamish River Powerhouse (Credit BC Hydro). Cover photos: Coho fry (Credit iStock) and Roosevelt Elk (Credit iStock). The Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program (FWCP) is a partnership between BC Hydro, the Province of BC, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, First Nations and Public Stakeholders to conserve and enhance fish and wildlife impacted by BC Hydro dams. The FWCP funds projects within its mandate to conserve and enhance fish and wildlife in 14 watersheds that make up its Coastal Region. Learn more about the Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program, projects underway now, and how you can apply for a grant at fwcp.ca. Subscribe to our free email updates and annual newsletter at www.fwcp.ca/subscribe. Contact us anytime at [email protected]. 2 Cheakamus River Action Plan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: CHEAKAMUS RIVER WATERSHED The Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program is a partnership between BC Hydro, the Province of B.C., Fisheries and Oceans Canada, First Nations and Public Stakeholders to conserve and enhance fish and wildlife impacted by BC Hydro dams. This Action Plan builds on the Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program’s (FWCP’s) strategic objectives, and is an update to the previous FWCP Watershed and Action Plans. -

“Salmon on the Rough Edge of Canada and Beyond”

“Salmon on the Rough Edge of Canada and Beyond” A Squamish Thanksgiving By Matt Foy Located in south-western British Columbia, Canada, the Squamish River is a large glacial fed watershed. The brawling mountain river, with its major tributaries such as the Elaho, Cheakamus, Ashlu, and Mamquam Rivers drains from the rugged terrain of the BC Coast mountains into the head of Howe Sound, part of the Salish Sea. Once known for its prolific runs of pink salmon these runs were decimated during the late- twentieth century. This is a story about their remarkable recovery and some of the people who worked hard to see pink salmon return to this beautiful mountain domain. As summer slid into fall, the phenomenal pink salmon run to the Squamish River was just winding down. The run of 2013 had exceeded all expectations, and such an abundance of pink salmon had not been observed in over fifty years, since the memorable return of 1963. For many people, the 2013 return would seem to have come out of nowhere but many other people understood the hard work and dedication that had led to this remarkable recovery. In that season of giving thanks, it seems fitting to reflect back on the path that has led from the last great run of 1963 to the years when pink salmon were almost absent from the Squamish River watershed, to the fall of 2013, one of great abundance to be celebrated and remembered. Upper Howe Sound, Squamish, BC, Canada Photo: Courtesy Ruth Hartnup Boom and Bust The growth decades of the 1950’s through the 1970’s were not kind to pink salmon populations around the Strait of Georgia. -

Influence of a Large Debris Flow Fan on the Late Holocene Evolution of Squamish River, Southwest British Columbia, Canada

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Influence of a large debris flow fan on the late Holocene evolution of Squamish River, southwest British Columbia, Canada Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2017-0150.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the Author: 02-Jan-2018 Complete List of Authors: Fath, Jared; University of Alberta, Renewable Resources Clague, John J.; Dept of Earth Sciences, Friele, Pierre;Draft Cordilleran Geoscience Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special N/A Issue? : Quaternary geology, Alluvial fans, Fan-impounded lakes, Squamish River, Keyword: Cheekye Fan https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Page 1 of 48 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Influence of a large debris flow fan on the late Holocene evolution of Squamish River, southwest British Columbia, Canada 1 2 3 4 Jared Fatha,c *, [email protected] Draft 5 John J. Claguea,*, [email protected] 6 Pierre Frieleb, [email protected] 7 8 a Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, 9 BC, V5A 1S6 10 b Cordilleran Geoscience, PO Box 612, Squamish, BC, V0N 3G0 11 c Presently at Department of Renewable Resources, University of Alberta, Edmonton 12 *Corresponding author 13 https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 48 2 1 Abstract 2 Cheekye Fan is a large paraglacial debris flow fan in southwest British Columbia. It owes its 3 origin to the collapse of Mount Garibaldi, a volcano that erupted in contact with glacier ice 4 near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch. The fan extended across Howe Sound, isolating a 5 freshwater lake upstream of the fan from a fjord downstream of it. -

Canada Cheakamus River Habitat Restoration Sue's Channel Project

Cheakamus River Habitat Restoration Sue’s Channel Project (06.CMS.01) Sue’s Channel Bridge March 2007 Canada Government of Canada North Vancouver Fisheries and Oceans Outdoor School Cheakamus River Salmon Habitat Restoration 06.CMS.01 “Sue’s Channel” Final Report This channel, and the educational opportunities that occur along its banks, are a memorial to Sue Emerson, and her dedication to the Bridge Coastal Restoration Program. Submitted by: Squamish River Watershed Society Prepared by: Carl Halvorson North Vancouver Outdoor School, School District #44 and Edith Tobe Squamish River Watershed Society with financial support of the BC Hydro Bridge Coastal Fish and Wildlife Restoration Program Executive Summary This project involved construction of new channel habitats and support structures for salmonid habitat located at North Vancouver Outdoor School (NVOS) (Sue’s Channel) and the restoration of channel habitats that were impacted by the October 2003 flood of record on the Cheakamus River and the August 5, 2005 CN Rail sodium hydroxide spill (Moody’s Channel), located on Squamish First Nation (SFN) I.R. 11. Design and engineering work were undertaken by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and NVOS staff during the winter of 2005 - 2006. Construction work started late in 2005 with right of way clearing to facilitate surveys for construction levels, grades and cuts. Initial excavation for the Sue's Channel complex area started in the spring of 2006. These early excavations were funded by the concurrent Mamquam Reunion project. Approx. 1200 m3 of alluvial gravels extracted on-site at NVOS were utilized in that project. Excavation started in earnest in late spring with the start of the "Moody's Channel" phase of the project. -

Investigating Cottid Recolonization in the Cheakamus River, Bc: Implications for Management

INVESTIGATING COTTID RECOLONIZATION IN THE CHEAKAMUS RIVER, BC: IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT By CAROLINE KOHAR ARMOUR B.Sc., University of Ottawa, 2001 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard .......................................................... Dr. Lenore Newman, MEM Program Head School of Environment and Sustainability .......................................................... Dr. Tom A. Watson, R.P. Bio., P. Biol., Senior Environmental Scientist Triton Environmental Consultants Ltd. .......................................................... Dr. Tony Boydell, Director School of Environment and Sustainability ROYAL ROADS UNIVERSITY February 2010 © Caroline Kohar Armour, 2010 Investigating Cottid Recolonization ii ABSTRACT An estimated 90% of resident sculpin (Cottus asper and C. aleuticus) were impacted by a spill of 45,000 litres of sodium hydroxide, which occurred on the Cheakamus River, British Columbia on August 5, 2005. This study examined sculpin biology, life history, how sculpins are recovering from the impact, and whether they are re-entering the Cheakamus River from the adjacent Squamish and Mamquam Rivers. Sculpins were sampled in the three river systems via minnow trapping and electrofishing. Morphometric data were recorded and fin clips were taken as deoxyribonucleic acid vouchers to validate field species identification and to determine population distinctiveness among the three systems. Populations were not distinct, suggesting recolonization from other rivers is occurring. The data show sculpins will undergo seasonal downstream spawning migrations and also suggest sculpins are opportunistic habitat colonizers. This research bears useful implications for the adaptive management, recovery, and sustainability of sculpins in the Cheakamus River. Investigating Cottid Recolonization iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

Serene Garibaldi Lake Hiking One of the Most Beautiful Trails in British Columbia by Mountain Man Dave Garibaldi Lake

Northwest Explorer ETTE J AVE D Glaciers of Mount Garibaldi above Garibaldi Lake, British Columbia. As either a day hike or an overnight, this is one of B.C.’s most spectacular hikes, chock full of views, wilflowers and wildlife. Serene Garibaldi Lake Hiking one of the most beautiful trails in British Columbia By Mountain Man Dave Garibaldi Lake. It is here that you pay for best ones, #26 and #27. These campsites your campsite permit, $5/person/night are located just before the second kitchen Shortly after Labor Day, Mo Swanson, (Canadian funds, cash only), for either shelter on the lake. This was a fortunate Cecile, and I took a five-day backpack to Garibaldi Lake or Taylor Meadows. choice, for the next day was pretty stormy Garibaldi Lake in Garibaldi Provincial (Campsites there are nonreservable, and and we spent most of the time inside Park, 1.5 hours north of Vancouver, B.C. those at Garibaldi Lake of course fill up the nearby shelter (fully enclosed, but On Thursday afternoon, September 7, first.) At first there is a climb of 2,530 feet without heat). 2006 we left Seattle and drove to the in 3.7 miles to a junction (4,430 feet), on There were still some low clouds on very nice large campground in Alice a wide well-graded, but totally boring, day three, but we set off early to climb Lake Provincial Park, ten miles short trail in woods. Here, the left fork leads the forbidding Black Tusk (7,598 feet), of the turnoff to the trail to Garibaldi up about 400 feet to Taylor Meadows a huge volcanic plug around which Lake. -

Canada Cheakamus River 2004 Mykiss Channel Project

Cheakamus River 2004 Mykiss Channel Project (04.Ch.01) Mykiss Channel October 2003 Canada Government of Canada North Vancouver Fisheries and Oceans Outdoor School Cheakamus River 2004 Mykiss Channel Project Final Report Submitted by: NorthVancouver Outdoor School School District #44 Prepared by: Carl Halvorson with financial support of the BC Hydro Bridge Coastal Fish and Wildlife Restoration Program Table of Contents Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Study Area 3. Methods 4. Results 5. Acknowledgements Appendices A. Financial Statements B. BCRP Recognition C. Restoration Details (maps / photos / drawings) 1. Site Locater 2. NVOS Site Map 3. Channel Overview Drawing 4. Reach Drawings 5. Photo Pages 1 - 4 6. Far Point intake site map D. Additional Information Executive Summary This project involved restructuring of the Far Point dike and intake structure and construction of a 400m side channel at North Vancouver Outdoor School. Approximately 80m of dike was reconstructed and the existing 2- 2ft intake pipes replaced with a single 3 ft pipe, headwall and valve assemblies. A 400m river fed side channel was constructed, providing 3840 m2 of new habitat. This project was link to other ongoing initiatives funded by various partnership groups including the School Protection Program, the Provincial Emergency Program, District of Squamish, School District #44 and the concurrent BCRP project 04.Ch.3 (Cheakamus River October 2003 Flood Restoration). Introduction The North Vancouver Outdoor School (NVOS) has worked with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and various funding partners to develop salmon habitat restoration projects on school property over the last two decades. These projects have been directed at improving spawning and rearing habitats for coho, chum, chinook and pink salmon.