Niobium Alloys and High Temperature Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

Development of Niobium-Boron Grain

DEVELOPMENT OF NIOBIUM-BORON GRAIN REFINER FOR ALUMINIUM-SILICON ALLOYS A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) by Magdalena Nowak Brunel Centre for Advanced Solidification Technology (BCAST) Brunel University September 2011 To my mother and my late father... II Abstract Aluminium castings with a large grain structure have poor mechanical properties which are primarily due to casting defects as opposed to fine grain structure. The grain refinement practice using chemical addition is well established for wrought alloys, however in the case of casting alloys, the practice of adding grain refiners and the impact on castability is not well established. The addition of well known Al-5Ti-B grain refiner to casting alloys with silicon (Si) content above 3 wt.% is not effective. This is believed to be due to the chemical reaction between Ti and Si. The current research aim is to find an alternative, but effective, chemical phase which can refine Al-Si alloy grains. Based on a crystallographic database search and intermetallic phases found in Aluminium–Niobium-Boron, there exists several iso-structural phases similar to those of Al3Ti and TiB2. We have selected a phase which exhibits chemical phase stability with Si (below 900 oC) and developed a potential novel grain refiner Nb-B for Al-Si cast alloys. Various Al-Si binary alloys and a commercial sourced LM6 (Al-10Si-Mg) cast alloys were cast after novel grain refiner addition to the melt. It is the first time that such fine grain structures were achieved for Al-Si alloys when Si >4wt.%. -

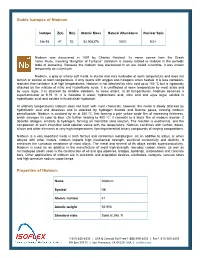

Stable Isotopes of Niobium Properties of Niobium

Stable Isotopes of Niobium Isotope Z(p) N(n) Atomic Mass Natural Abundance Nuclear Spin Nb-93 41 52 92.906376 100% 9/2+ Niobium was discovered in 1801 by Charles Hatchett. Its name comes from the Greek name Niobe, meaning “daughter of Tantalus” (tantalum is closely related to niobium in the periodic table of elements). Because the niobium was discovered in an ore called columbite, it was known temporarily as columbium. Niobium, a gray or silvery soft metal, is ductile and very malleable at room temperature and does not tarnish or oxidize at room temperature. It only reacts with oxygen and halogens when heated. It is less corrosion- resistant than tantalum is at high temperatures. Niobium is not attacked by nitric acid up to 100 °C but is vigorously attacked by the mixture of nitric and hydrofluoric acids. It is unaffected at room temperature by most acids and by aqua regia. It is attacked by alkaline solutions, to some extent, at all temperatures. Niobium becomes a superconductor at 9.15 °K. It is insoluble in water, hydrochloric acid, nitric acid and aqua regia; soluble in hydrofluoric acid; and soluble in fused alkali hydroxide. At ordinary temperatures niobium does not react with most chemicals; however, the metal is slowly attacked by hydrofluoric acid and dissolves and is attacked by hydrogen fluoride and fluorine gases, forming niobium pentafluoride. Niobium is oxidized by air at 350 ºC, first forming a pale yellow oxide film of increasing thickness, which changes its color to blue. On further heating to 400 ºC, it converts to a black film of niobium dioxide. -

Separation of Niobium and Tantalum - a Literature Survey Ernest L

Ames Laboratory ISC Technical Reports Ames Laboratory 8-15-1956 Separation of niobium and tantalum - a literature survey Ernest L. Koerner Iowa State College Morton Smutz Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ameslab_iscreports Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Koerner, Ernest L. and Smutz, Morton, "Separation of niobium and tantalum - a literature survey" (1956). Ames Laboratory ISC Technical Reports. 145. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ameslab_iscreports/145 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Ames Laboratory at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ames Laboratory ISC Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Separation of niobium and tantalum - a literature survey Abstract During recent years increased interest has been shown in the metal niobium. Because niobium has a high melting point (4376° F) and a low neutron cross-section, the Atomic Energy Commission has encouraged research on new methods of winning the metal from its ores with the ultimate hope of finding a process which would yield niobium metal at a reasonable price. The two areas of endeavor in which·the principal difficulties in finding such an economic process occur are the separation of tantalum from the niobium and the conversion of purified niobium salts to the metal. This report, then, was written to consolidate the more important information available in the literature on one of these troublesome areas, that of the separation of niobium and tantalum. -

Effect of Oxygen on the Corrosion of Niobium and Tantalum by Liquid Lithium

ORNL-TM-4069 DECEIVED BY TIC MAR 2 01973 THE EFFECT OF OXYGEN ON THE CORROSION OF NIOBIUM AND TANTALUM BY LIQUID LITHIUM R. L. Klueh MASTER SiSTiHBUTWfl c-f THIS &3CmMT 13 U&UMITED r. I . • -I ' / •''Hi'; 1 . V/', •• I • • H I •-' , C •!", >i ; ' o ': 'J -1 ; .•..'.' •-•'I' < . • . .J ,• ! OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY '-I. ' ' t- /operated'by "unjon 'carbide, coloration • forjhe'u.s. atowic1 ENERGY'CQMMISSION 1 • - " <•:-.*- '' .1 iS> '•'• . ' , 1 <• \ .1 I . 'v: • = 1 r i. H. ORNL-TM-4069 Contract No. W-7405-eng-26 METALS AND CERAMICS DIVISION THE EFFECT OF OXYGEN ON THE CORROSION OF NIOBIUM AND TANTALUM BY LIQUID LITHIUM R. L. Klueh NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neither the United States noi' the United States Atomic Energy Commission, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility fir the accuracy, com- pleteness or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. MARCH 1973 OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37830 operated by • i UNION CARBIDE CORPORATION for the U.S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION MASTER • • • 11X CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Experimental 5 Results ...... 7 The Effect of Oxygen in Lithium 7 The Effect of Oxygen in the Refractory Metal 9 Discussion ........ 16 Acknowledgments 21 THE EFFECT OF OXYGEN ON THE CORROSION OF NIOBIUM AND TANTALUM BY LIQUID LITHIUM R. L. -

Niobium Pentoxide Based Materials for High Rate Rechargeable Electrochemical Energy Storage Cite This: Mater

Materials Horizons View Article Online REVIEW View Journal | View Issue Niobium pentoxide based materials for high rate rechargeable electrochemical energy storage Cite this: Mater. Horiz., 2021, 8, 1130 Fei Shen,a Zhongti Sun,ab Qinggang He, *c Jingyu Sun, abd Richard B. Kaner *e and Yuanlong Shao*abd The demand for high rate energy storage systems is continuously increasing driven by portable electronics, hybrid/electric vehicles and the need for balancing the smart grid. Accordingly, Nb2O5 based materials have gained great attention because of their fast cation intercalation faradaic charge storage that endows them with high rate energy storage performance. In this review, we describe the crystalline features of the five main phases of Nb2O5 and analyze their specific electrochemical characteristics with an emphasis on the intrinsic ion intercalation pseudocapacitive behavior of T-Nb2O5. The charge Received 14th September 2020, storage mechanisms, electrochemical performance and state-of-the-art characterization techniques for Accepted 9th December 2020 Nb2O5 anodes are summarized. Next, we review recent progress in developing various types of Nb2O5 DOI: 10.1039/d0mh01481h based fast charging electrode materials, including Nb2O5 based mixed metal oxides and composites. Finally, we highlight the major challenges for Nb2O5 based materials in the realm of high rate rechargeable rsc.li/materials-horizons energy storage and provide perspectives for future research. 1. Introduction Due to the increasing demand for rapid charging and high power a College of Energy, Soochow Institute for Energy and Materials InnovationS delivery for portable electronics and electricvehicles,highrate (SIEMIS), Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory for Advanced Carbon Materials and energy storage systems (ESSs) that can store/release charge in Wearable Energy Technologies, Soochow University, 215006 Suzhou, P. -

(Nb-Ti) Superconducting Joints for Persistent-Mode Operation

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Niobium-titanium (Nb-Ti) superconducting joints for persistent-mode operation Received: 21 June 2019 Dipak Patel1,2, Su-Hun Kim1,3, Wenbin Qiu1, Minoru Maeda4, Akiyoshi Matsumoto2, Accepted: 26 August 2019 Gen Nishijima2, Hiroaki Kumakura2, Seyong Choi4 & Jung Ho Kim1 Published: xx xx xxxx Superconducting joints are essential for persistent-mode operation in a superconducting magnet system to produce an ultra-stable magnetic feld. Herein, we report rationally designed niobium- titanium (Nb-Ti) superconducting joints and their evaluation results in detail. For practical applications, superconducting joints were fabricated by using a solder matrix replacement method with two types of lead-bismuth (Pb-Bi) solder, including Pb42Bi58 as a new composition. All the joints attained a critical current of >200 A below 1.43 T at 4.2 K. Our optimized superconducting joining method was tested in a closed-loop coil, obtaining a total circuit resistance of 3.25 × 10−14 Ω at 4.2 K in self-feld. Finally, persistent-mode operation was demonstrated in an Nb-Ti solenoid coil with a persistent-current switch. This work will pave the way to developing high-performance Nb-Ti superconducting joints for practical applications. Superconducting magnets are used to produce a strong magnetic feld in a compact system, which otherwise cannot be attained using conventional copper (Cu) based magnets. Niobium-titanium (Nb-Ti) with a critical temperature (Tc) of 9.2 K is usually used to fabricate superconducting magnets for various practical applications. One of the distinct features of Nb-Ti that makes it ideal for most commercial applications is the possibility to produce reliable “superconducting joints”. -

Future Possibilities – Technology and the Market Place

NIOBIUM: FUTURE POSSIBILITIES – TECHNOLOGY AND THE MARKET PLACE Friedrich Heisterkamp(1) and Tadeu Carneiro(2) (1) Niobium Products Company GmbH, Steinstrasse 28, D-40210 Düsseldorf 1, Germany. (2) Reference Metals Company, Inc.,1000 Old Pond Road, Bridgeville, PA 15017-0217, U.S.A. Abstract Although niobium is now two hundred years old, it has been only during the past four decades that it has been consumed as an industrial material. During this time, niobium has been established as part of the engineering solution in numerous cases for its own technical merits. The most important of these cases are in the field of oil and gas transportation, automotive industry, high-rise buildings, aircraft engines and medical diagnosis devices. The future will see niobium as an increasingly important technological solution in a broad spectrum of end- uses as specific niobium properties continue to be investigated. The bulk of niobium will continue to go into steel since its present position is unchallenged in the three main microalloyed steel domains (pipe, automotive and structurals). In pipe steels niobium will remain a chief microalloying element in all steel grades. In automotive steels it will remain the most important microalloying element in all hot and cold rolled HSLA steels with a good chance to penetrate the new and important group of multi-phase steels. In addition, it is expected that all thermomechanically processed high strength steels for structural components will contain niobium as the first microalloy choice in the future. With regard to the non-ferrous applications niobium will be rather used for high value-added products. -

The Radiochemistry of Niobium and Tantalum

-._. -..—..-—-- National Academy v’” of Sciences Iational Research Council NUCLEAR SCIENCE SERIES The Radiochemistry of Niobium and Tantalum -—– J-.’ COMMITTEE ON NUCLEAR SCIENCE L. F. CURTISS, Chabman ROBLEY D. EVANS, Vice Chairman National Bureau of Stawiarda Massachusetts Instituteof Technology J. A. DeJUREN, Secre&wy WeMnghouae Electric Corporation C. J. BORKOWSKI J. W. IRVINE, JR. Oak Ridge National Laboratory Massachusetts Instituteof Technology ROBERT G. COCHRAN E. D. KLEMA Texas Agricultural and Mechanical Northwestern”University College W. WAYWE MEINKE SAMUEL EPSTEIN University of Michigan California Instituteof Technology J. ,J. NICKSON U. FANO Memorial Hospital, New York National Bureati of Standarde ROBERT L. PLATZMAN Laboratoire de Chimie Physique HERBERT GOLDSTEIN Nuclear Development Corpratlon of D. M. VAN PATTER -rica Bmtol Research Foundation LIAISON MEMBERS PAUL C. AEBERSOLD CHARLES K. REED Atomic Ene~ Commission U. S. Air Force J. HOWARD McNHLLEN WfLLLAM E. WRIGHT National Science Foundation Office of Naval Researoh SUBCOMMITTEE ON RADIOCHEMISTRY W. WAYNE MEINKE, Chairnuzu HAROLD KIRBY Univer.ai@ of Michigan Mound Lahratmy GREGORY R. CHOPPIN GEORGE LEDDICOTTE Florida State University Oak Ridge National Laboratory GEORGE A. COWAN JULIAN NTELSEN Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Hanfoni Laboratories ARTHUR W. FAIRHALL ELLIS P. STEINBERG University of Washington Argome National Laboratory JEROME HUDIS PETER C. STEVENSON Brookhaven National Laboratory Universi@ of California (Livermore) EARL HYDE LEO YAFFE Universi@ of California (Berkeley) McGill Universi~ CONSULTANTS NATRAN BALLOU” JAMES DeVOE Naval Radiologic@ Defe,pseLaboratory Univer.9i@ of Michigan WILLIAM MARLOW National Bureau of Standarda CHEMISTRY The Radiochemistry of Niobium and Tantalum ELLIS P. STEINBERG Argonne National Labo?’atovy 97OO South Cass Avenue Argonne, IiWnois t“ August1961 z s PRO‘=‘k, Subcommittee on Radiochemistry National Academy of Sciences—National Research Council Prfntedin U6A. -

THE EVOLUTION of Fenb MANUFACTURING

THE EVOLUTION OF FeNb MANUFACTURING Clóvis Antonio de Faria Sousa CBMM - Companhia Brasileira de Metalurgia e Mineração Córrego da Mata s/n – P.O. Box 08 38.183-970 - Araxá, MG, Brazil Abstract This paper describes ferro-niobium manufacturing technology, and comments on alternative methods of production. A brief history of niobium illustrates the evolution of its applications and, as a consequence, the evolution of ferro-niobium manufacturing. The execution of industrial projects by the major niobium supplier, CBMM, is described, including the recent expansion plan, which has increased ferro-niobium production capacity to 45,000 t/y. CBMM’s future plans regarding ferro-niobium manufacturing technology are also discussed. Introduction In less than two centuries niobium has evolved from being an unknown metal to a rare and high-priced material in the market, and then to the opposite extreme, becoming readily available, with an excess of supply and reduced price. In 1801, Charles Hatchett, a British chemist, discovered an element that he named columbium, since the mineral sample he was working with came from New England in the United States. However, Hatchett did not isolate the element. This was done by Heinrich Rose, a German, who separated an impure Nb2O5 from tantalite in 1844. Thinking that he had found a new element, Rose renamed it niobium, which remained a laboratory curiosity for nearly 100 years. In 1948, niobium was adopted as the name for the element by the International Union of Chemists, although the original name columbium is still widely used by metallurgists in North America. Applications of niobium began around 1925 when it was added to tool steels as a partial substitute for tungsten, and later in 1933 when it was first used to stabilise interstitial in austenitic stainless steels. -

Incorporation of Refractory Metals Into Niobium Base Alloys A

Incorporation of Refractory Metals into Niobium Base Alloys A. Antoni-Zdziobek, J. Driole, Franck Durand To cite this version: A. Antoni-Zdziobek, J. Driole, Franck Durand. Incorporation of Refractory Metals into Niobium Base Alloys. Journal de Physique IV Proceedings, EDP Sciences, 1995, 05 (C7), pp.C7-129-C7-134. 10.1051/jp4:1995711. jpa-00254004 HAL Id: jpa-00254004 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/jpa-00254004 Submitted on 1 Jan 1995 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL DE PHYSIQUE IV Colloque C7, supplkment au Journal de Physique 111, Volume 5, novembre 1995 Incorporation of Refractory Metals into Niobium Base Alloys A. Antoni-Zdziobek, J. Driole and F. Durand ZNP de Gi-enoble et CNRS, EPM-Madylam, ENSHMG, BP. 95, 38402 Saint-Martin-dfH2res, France Abstract : Niobium-based alloys with additions such as Al, Ti and Mo were prepared in an inductive cold crucible. A process route was established to provide homogeneous ingots. Key ideas concerning the application of inductive cold crucible to preparation of refractory alloys are brought out. A model is proposed to explain and quantify the experimental observations, which couples the diffusive and convective heat transfers and the heat of mixing involved. -

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged To

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged to Four and Five Significant Figures Norman E. Holden Energy Sciences & Technology Department National Nuclear Data Center Brookhaven National Laboratory P.O. Box 5000 Upton, NY 11973-5000 www.bnl.gov Prepared for the 44th IUPAC General Assembly, in Torino, Italy August 2007 Notice: This manuscript has been authored by employees of Brookhaven Science Associates, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The publisher by accepting the manuscript for publication acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. This preprint is intended for publication in a journal or proceedings. Since changes may be made before publication, it may not be cited or reproduced without the author’s permission. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof or its contractors or subcontractors.