Proposed Strategy for Decreasing the Illegal Logging and Trade of Rosewood (Dalbergia Spp.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID. The project has been financed by the CITES Secretariat with funds from the European Union Consulting objectives: TO SELECT INTERNATIONAL OR NATIONAL XYLARIUM OR WOOD COLLECTIONS REGISTERED AT THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOOD ANATOMISTS – IAWA THAT HAVE A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER OF SPECIES AND SPECIMENS OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA TO BE ANALYZED BY NIRS TECHNOLOGY. Consultant: VERA TERESINHA RAUBER CORADIN Dra English translation: ADRIANA COSTA Dra Affiliations: - Forest Products Laboratory, Brazilian Forest Service (LPF-SFB) - Laboratory of Automation, Chemometrics and Environmental Chemistry, University of Brasília (AQQUA – UnB) - Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC-DF MAY, 2020 Brasília – Brazil 1 Project number: S1-32QTL-000018 Host Country: Brazilian Government Executive agency: Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC Project coordinator: Dra. Tereza C. M. Pastore Project start: September 2019 Project duration: 24 months 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 05 2. THE SPECIES OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA 05 3. MATERIAL AND METHODS 3.1 NIRS METHODOLOGY AND SPECTRA COLLECTION 07 3.2 CRITERIA FOR SELECTING XYLARIA TO BE VISITED TO OBTAIN SPECTRAS 07 3 3 TERMINOLOGY 08 4. RESULTS 4.1 CONTACTED XYLARIA FOR COLLECTION SURVEY 10 4.1.1 BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 10 4.1.2 INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 11 4.2 SELECTED XYLARIA 11 4.3 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 13 4.4 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 14 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 6. REFERENCES 20 APPENDICES 22 APPENDIX I DALBERGIA IN BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 22 CACAO RESEARCH CENTER – CEPECw 22 EMÍLIO GOELDI MUSEUM – M. -

Cocobolo Samuel J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Yale University Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series 1923 Cocobolo Samuel J. Record George A. Garratt Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Recommended Citation Record, Samuel J., and George A. Garratt. 1923. ocC obolo. Yale School of Forestry Bulletin 8. 42 pp. + plates This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Note to Readers 2012 This volume is part of a Bulletin Series inaugurated by the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 1912. The Series contains important original scholarly and applied work by the School’s faculty, graduate students, alumni, and distinguished collaborators, and covers a broad range of topics. Bulletins 1-97 were published as bound print-only documents between 1912 and 1994. Starting with Bulletin 98 in 1995, the School began publishing volumes digitally and expanded them into a Publication Series that includes working papers, books, and reports as well as Bulletins. -

(CITES) on Various Stakeholders in the Music Industry

Impacts of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) on various Stakeholders in the Music Industry Figure 1: Guitar manufacturing, Source: (Voigt-Luthiers Gitarren, 2018). On behalf of Swiss Wood Solutions AG Author: Elias Wick July, 2019 Table of Content Table of Content .................................................................................................................................................. i List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................... ii 1. From Raw Wood to a World Tour ................................................................................................................. 3 2. Impacts on Instrument Manufacturers in the United States ........................................................................ 5 3. What about the Musicians? ........................................................................................................................... 9 4. Conclusion and Alternatives to CITES-protected Wood Species ................................................................. 11 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Annex .............................................................................................................................................................. -

PC23 Doc. 22.2

Original language: English PC23 Doc. 22.2 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-third meeting of the Plants Committee Geneva, (Switzerland), 22 and 24-27 July 2017 Species specific matters Rosewood timber species [Leguminosae (Fabaceae)] INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ROSEWOOD SPECIES 1. This document has been submitted by the European Union (EU) and developed in consultation with its Member States*. Background 2. At the 17th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention (24 September – 4 October 2016, CITES CoP17), the following taxa were included in CITES Appendix II: – all rosewood and palisander species of the genus Dalbergia; – Pterocarpus erinaceus (kosso); Guibourtia demeusei; Guibourtia pellegriniana; Guibourtia tessmannii (bubinga). These decisions were adopted on the basis of the high volumes of international trade and the detrimental impact of illegal and unsustainable logging on the conservation of these species. This decision did not affect the listing of the Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra), which was included in Appendix I to the Convention in 1992 and remains listed in this Appendix. A number of other Dalbergia species1 had already been listed in CITES Appendix II since 2013, and remain listed in Appendix II. The new listings in Appendix II adopted at CoP17 entered into force at the international level on 2 January 2017, and have been implemented at EU level through amendments to the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations2. The EU wishes to share with Parties its experience in implementing these new listings since their entry into force. 3. The listing of Pterocarpus erinaceus (kosso) in Appendix II to the Convention is not accompanied by any annotation, meaning that all parts and derivatives of this species are covered by the provisions of the Convention. -

Stay Sharp B Ill Carroll

r 72 gt a hadl o kif akig ad stay sharp y ill carroll Knife making has become a popular endeavor for woodworkers of all skill levels. This beginner’s guide will get you started. { no. 59 } rom cutting and marking in the Fshop, to hunting and camping, to preparing a simple meal, a good knife is indispensable. Mass-produced knives gt a hadl o kif akig ad can be found for every budget and use. But custom knives, which are often far more attractive, tend to get expensive very quickly. stay sharp Of course, the ultimate custom 1 2 knife would include a hand-forged and hand-sharpened blade. If you’re not up for the expense and dirty work of such an endeavor, you can still experience the pride of a well-crafted and functional addition to your tool collection. All you need is a knife kit. It’s all in there 3 4 A knife kit consists of a prefabricated blade and pins, which allows the maker to select handle materials, assemble Select wood for your scales and the knife, and shape and polish it to determine which sides will face away perfection. It requires minimal tools, from the handle portion of the knife good attention to aesthetic detail and blank, or the “tang.” Using the blank, a few hours of shop time. Once you’ve trace the shape of the tang onto each gained some knife-making experience, scale (Fig. 3). Make sure to trace the there are hundreds of types of knives tang in the proper orientation to keep (and swords, and spears) available as the best woodgrain on the visible 5 kits from a number of sources. -

10-Inch Drum Sander

10-INCH DRUM SANDER For replacement parts visit Model # 65910 WENPRODUCTS.COM bit.ly/wenvideo IMPORTANT: Your new tool has been engineered and manufactured to WEN’s highest standards for dependability, ease of operation, and operator safety. When properly cared for, this product will supply you years of rugged, trouble-free performance. Pay close attention to the rules for safe operation, warnings, and cautions. If you use your tool properly and for its intended purpose, you will enjoy years of safe, reliable service. NEED HELP? CONTACT US! Have product questions? Need technical support? Please feel free to contact us at: 800-232-1195 (M-F 8AM-5PM CST) [email protected] WENPRODUCTS.COM NOTICE: Please refer to wenproducts.com for the most up-to-date instruction manual. TABLE OF CONTENTS Technical Data 2 Safety Introduction 3 General Safety Rules 4 Electrical Information 6 Specific Rules for Drum Sanders 7 Know Your Drum Sander 8 Unpacking 9 Assembly 10 Preparation 14 Operation 18 Adjustments 19 Maintenance 22 Troubleshooting 24 Exploded View and Parts List 26 Warranty Statement 30 TECHNICAL DATA Model Number: 65910 Motor: 120V, 60Hz, 10.5A Drum Speed: 1440 RPM Sandpaper Speed: 2300 FPM Conveyor Feed Speed: 0 to 10 FPM Maximum Workpiece Width: 9-1/2 in. (240mm) Minimum Workpiece Width: 3/4 in. (19mm) Maximum Workpiece Height: 3 in. (75mm) Minimum Workpiece Height: 1/4 in. (6mm) Minimum Workpiece Length 4-3/4 in. (120mm) Sandpaper Width: 3 in. Sandpaper Length: 62-1/2 in. Sanding Drum Size: 5-1/8 x 10 in. (132 x 255mm) Dust Port Diameter: 3.9 in. -

Panama’S Illegal Rosewood Logging Boom from Dalbergia Retusa

Global Ecology and Conservation 23 (2020) e01098 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Panama’s illegal rosewood logging boom from Dalbergia retusa * Ella Vardeman a, b, d, , Julie Velasquez Runk a, c a University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602, USA b City University of New York, Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave, New York, NY, 10016, USA c Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panama d The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), Institute of Economic Botany, 2900 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, NY 10458, USA article info abstract Article history: Over the last decade, illegal rosewood logging has surged worldwide, with much attrib- Received 9 December 2019 utable to an uptick in Chinese demand. For the last seventy-five years, Panama’s main use Received in revised form 30 April 2020 of cocobolo rosewood (Dalbergia retusa) was in small pieces for artisanal carvings, its state Accepted 30 April 2020 of conservation favoring merchantable timber for recent exploitation with the surging market. Panama’s cocobolo rosewood boom was from 2011 to 2015 and, given regulations, Keywords: was largely illicit. However, no data on cocobolo logging have been made public. Here, we Dalbergia retusa assess Panama’s cocobolo logging. We used a media analysis of Panamanian and inter- Panama Media analysis national reports on cocobolo logging from January 2000 to February 2018 coupled with Illegal logging long-term socio-environmental research to show how logging changed during the boom. We conducted a content analysis of articles to address four specific objectives: 1) to assess how cocobolo logging intensity changed over time; 2) to determine what topics related to logging were important for the press to relay to the public; 3) to show how logging changed geographically as the boom progressed; 4) to demonstrate how Panama and the international community responded to the global boom with new policies on rosewood governance. -

Brook Milligan NMSU.Pdf

Identifying Samples and their Sources: Case Studies and Lessons Learned Brook Milligan Conservation Genomics Laboratory Department of Biology New Mexico State University Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003 USA [email protected] Development and Scaling of Innovative Technologies for Wood Identification February 28, 2017 © 2017 Brook Milligan, NMSU Identifying Samples and their Sources February 28, 2017 1 / 29 The questions we face What is its taxonomic identity? 5 Sample / ? ) Where did it come from? Case studies I Taxonomic identification via direct comparison with a database I Taxonomic identification via inference I Geographic origin identification via inference Lessons learned I Direct comparison is of limited usefulness I Inference is essential for taxonomic and geographic origin identification I These lessons apply to all identification methods, not just DNA © 2017 Brook Milligan, NMSU Identifying Samples and their Sources February 28, 2017 2 / 29 Traditional genetics: a cottage industy Oak Heaps of Individually sample / taxon-specific / selected / lab work markers © 2017 Brook Milligan, NMSU Identifying Samples and their Sources February 28, 2017 3 / 29 Traditional genetics: an inefficient cottage industry Oak Heaps of Individually sample / taxon-specific / selected / lab work markers Rosewood Heaps of Individually sample / taxon-specific / selected / lab work markers Maple Heaps of Individually sample / taxon-specific / selected / lab work markers © 2017 Brook Milligan, NMSU Identifying Samples and their Sources February 28, 2017 4 / 29 Traditional -

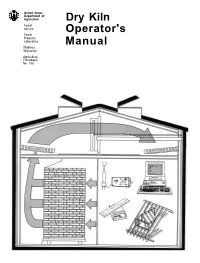

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

A Guide to Lesser Known Tropical Timber Species July 2013 Annual Repo Rt 2012 1 Wwf/Gftn Guide to Lesser Known Tropical Timber Species

A GUIDE TO LESSER KNOWN TROPICAL TIMBER SPECIES JULY 2013 ANNUAL REPO RT 2012 1 WWF/GFTN GUIDE TO LESSER KNOWN TROPICAL TIMBER SPECIES BACKGROUND: BACKGROUND: The heavy exploitation of a few commercially valuable timber species such as Harvesting and sourcing a wider portfolio of species, including LKTS would help Mahogany (Swietenia spp.), Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata), Ramin (Gonostylus relieve pressure on the traditionally harvested and heavily exploited species. spp.), Meranti (Shorea spp.) and Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.), due in major part The use of LKTS, in combination with both FSC certification, and access to high to the insatiable demand from consumer markets, has meant that many species value export markets, could help make sustainable forest management a more are now threatened with extinction. This has led to many of the tropical forests viable alternative in many of WWF’s priority places. being plundered for these highly prized species. Even in forests where there are good levels of forest management, there is a risk of a shift in species composition Markets are hard to change, as buyers from consumer countries often aren’t in natural forest stands. This over-exploitation can also dissuade many forest willing to switch from purchasing the traditional species which they know do managers from obtaining Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification for the job for the products that they are used in, and for which there is already their concessions, as many of these high value species are rarely available in a healthy market. To enable the market for LKTS, there is an urgent need to sufficient quantity to cover all of the associated costs of certification. -

Soundwood: Make Music Conserve Trees

Madagascar Stockpile Audit Mechanism and Business Plan Robert Garner Director ForestBased Solutions, LLC ForestBased Works Globally • Currently work in over 15 countries • Large scale industrial forests • Community forests • Manufacturers / Suppliers • Mills • Supply Chain Mgt ForestBased Solutions • Promote market-based incentives to Private Sector that merge the triple bottom line social, economic and environmental objectives; • Promote and develop sourcing initiatives for high quality timber from responsibly managed forests; • Provide due diligence and technical expertise for investment in sustainable forestry • We work from Global Policy all the way to the ground with forest managers and forest dependent people. • Clients include governments, private sector, NGOs . Pioneered Species Specific Programs • Sustainable Forest Management • Private Sector and NGOs • Key Economic Indicators • Ebony - Cameroon • Rosewood - India, Tanzania, Madagascar, Central America • Mahogany - Brazil • Whole forest needs to be managed for species specific issues to be addressed Madagascar Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.) • Over 300 species • 10-15 are commercial • Indian • Central and South America • Madagascar • Entire Genus is CITES App II India Dalbergia latifolia • Most widely used • Southern India • Mix from Coffee estates and Gov forests • Gov Auctions Tanzania Dalbergia melanoxylon • African Blackwood • East Africa • Tanzania and Mozambique • Woodwinds Brazil Brazilian Rosewood • Dalbergia nigra • Atlantic Forest • 400 years of use and exploitation • 1992 -

Chapter 3--Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood

Chapter 3 Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood William Simpson and Anton TenWolde he versatility of wood is demonstrated by a wide Contents variety of products. This variety is a result of a Appearance 3–1 spectrum of desirable physical characteristics or properties among the many species of wood. In many cases, Grain and Texture 3–1 more than one property of wood is important to the end Plainsawn and Quartersawn 3–2 product. For example, to select a wood species for a product, the value of appearance-type properties, such as texture, grain Decorative Features 3–2 pattern, or color, may be evaluated against the influence of Moisture Content 3–5 characteristics such as machinability, dimensional stability, Green Wood and Fiber Saturation Point 3–5 or decay resistance. Equilibrium Moisture Content 3–5 Wood exchanges moisture with air; the amount and direction of the exchange (gain or loss) depend on the relative humid- Sorption Hysteresis 3–7 ity and temperature of the air and the current amount of water Shrinkage 3–7 in the wood. This moisture relationship has an important Transverse and Volumetric 3–7 influence on wood properties and performance. This chapter discusses the physical properties of most interest in the Longitudinal 3–8 design of wood products. Moisture–Shrinkage Relationship 3–8 Some physical properties discussed and tabulated are influ- Weight, Density, and Specific Gravity 3–11 enced by species as well as variables like moisture content; Working Qualities 3–15 other properties tend to be independent of species. The thor- oughness of sampling and the degree of variability influence Decay Resistance 3–15 the confidence with which species-dependent properties are Thermal Properties 3–15 known.