Master-Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Gender in the Arts Le Genre Dans Les Arts

DOCUMENTATION AND INFORMATION CENTRE CENTRE DE DOCUMENTATION ET D’INFORMATION Gender in the Arts Le genre dans les arts Bibliography - Bibliographie CODICE June/Juin, 2006 Gender in the Arts – Le genre dans les arts Introduction Introduction The topic of the 2006 session of the Gender La session 2006 de l’institut du genre porte sur Institute is “Gender in the arts”. The arts have « le Genre dans les arts ». been defined according to the Larousse dictionary Les arts, définis d’après le Larousse comme étant as being “All specific human activities, based on « l’ensemble des activités humaines spécifiques, sensory, aesthetic and intellectual faculties”. In faisant appel à certaines facultés sensorielles, other words, arts relate to: music, painting, esthétiques et intellectuelles ». En d’autres theatre, dance, cinematography, literature, termes, les arts se confondent à tout ce qui se orature, fashion, advertisement etc. rapporte à : la musique, la peinture, le théâtre, la danse, le cinéma, la littérature, l’oralité, la mode, This bibliography produced by the CODESRIA la publicité etc. Documentation and Information Centre (CODICE) within the framework of this institute lists Cette bibliographie produite par le Centre de documents covering all the concepts on arts. It is documentation et d’information du CODESRIA divided into four parts: (CODICE) dans le cadre de cet institut recense - References compiled from CODICE Bibliographic des documents en prenant en considération tous data base; les concepts liés aux arts. Elle est divisée en - New documents ordered for this institute; quatre parties : - Specialized journals on the topic of gender and - Les références tirées de la base de arts; données du CODICE. -

No. 361, October 2017

Pour la version française cliquez ici. Observatory of Cultural Policies in Africa The Observatory is a Pan African international NGO created in 2002 with the support of African Union, the Ford Foundation, and UNESCO. Its aim is to monitor cultural trends and national cultural policies in the region and to enhance their integration in human development strategies through advocacy, information, research, capacity building, networking, co-ordination, and co-operation at the regional and international levels. OCPA NEWS No 361 October 2017 OCPA News aims to promote interactive information exchange within Africa and between Africa and the other regions. Please send us information for dissemination about new initiatives, meetings, research projects and publications of interest for cultural policies for development in Africa. Thank you for your co-operation. *** Contact: OCPA Secretariat, Avenida Patrice Lumumba No. 850, Primeiro Andar, Caixa Postal 1207, Maputo, Mozambique Tel.: + 258 21306138 / Fax: +258 21320304 / E-mail: [email protected] Executive Director: Lupwishi Mbuyamba, [email protected] Editor of OCPA News: Máté Kovács, [email protected] 1 OCPA WEB SITE - www.ocpanet.org OCPA FACEBOOK - www.facebook.com/pages/OCPA-Observatory-of-Cultural-Policies-in- Africa/100962769953248?v=info You can subscribe or unsubscribe to OCPA News via the online form at http://www.ocpanet.org/activities/newsletter/mailinglist/subscribe-en.html or http://www.ocpanet.org/activities/newsletter/mailinglist/unsubscribe-en.html Previous issues of OCPA News at http://ocpa.irmo.hr/activities/newsletter/index-en.html * OCPA is an official partner of UNESCO (associate status) *** We express our thanks to our main partners whose support has permitted the development of our activities: ENCATC CBAAC FORD FOUNDATION *** *** 2 In this issue A. -

ELIOT ELISOFON: BRINGING AFRICAN ART to LIFE By

ELIOT ELISOFON: BRINGING AFRICAN ART TO LIFE by KATHERINE E. FLACH Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Dr. Constantine Petridis, Co-Advisor Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Katherine E. Flach ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Catherine B. Scallen (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Constantine Petridis ________________________________________________ Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Jonathan Sadowsky ________________________________________________ DATE OF DEFENSE March 4, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 This dissertation is dedicated to my family John, Linda, Liz and Sam 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... 11 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 12 Eliot Elisofon and African Art: An Introduction ........................................................ 14 Elisofon and LIFE ...................................................................................................... -

Aussereuropäische Kunst & Kultur Im Dialog Museum

Aussereuropäische Kunst & Kultur im Dialog Kunst&Kontext Museum - Sammler - Universität - Händler HUMBOLDT-BOx HUMBOLDT-LaB HUMBOLDT-FORUM: Die Beteiligten 0Ausgabe5 Zeitschrift 2013 Vereinigung der Freunde afrikanische Kultur e.V. Mühlebachstrasse 14 · 8008 Zürich · Switzerland · Tel. +41 44 280 20 00 · [email protected] · www.walu.ch KUNST&KONTEXT 1/2013 EDITORIAL 1 VORAB! Bundeskanzlerin wird überhaupt nicht teil- indigenen Gemeinschaften, den Nachfahren nehmen und der Bundespräsident lediglich der Hersteller, bearbeitet und ausgewählt passiv (nicht redend) anwesend sein. Ein ei- wurde. Beides wird es nicht geben. Denn genartiges Signal, wenn man bedenkt, dass ein ausreichender Etat hierfür existiert die außereuropäischen Sammlungen ganz nicht, weil die politisch Verantwortlichen besonderes Welt-Kulturerbe sind, Zeug- ihn vergessen haben. So ist das derzeitige Hier wird (nur?) ein Schloss gebaut! nisse vergangener Vielfalt. Sehr vieles noch Werbeplakat an der Baustelle „Hier wird ein Spätestens mit der Grundsteinlegung unverstanden und unentdeckt. Durch die Schloss gebaut“ ebenfalls ein Signal: Kein am 12. Juni 2013 ist klar: Die preußische Sammlungsgeschichte sind wir mit Tausen- Wort über die außereuropäischen Samm- Schlossfassade wird ab 2019 wieder das den Völkern und Stämmen verbunden. Die lungen und die Kulturen der Welt! Das Ti- Stadtbild in der Mitte Berlins prägen. Mit Objekte sind Kontakt-Konserven, mögliche telbild zeigt ein Modell des preußischen 595 Millionen Baukosten ist es ein weiteres Ausgangspunkte von Begegnungen in der Schlosses, umgeben von Politikern ver- Prestigeprojekt Deutschlands im Berlin des Gegenwart, wenn wir sie öffnen. Die Initia- schiedener Parteien. Als Symbol zufälliger NachDemFallDerMauer-Zeitalters, in einer tive muss von uns ausgehen, denn nur wir Objektauswahl für die Eröffnungsausstel- Linie mit dem Kanzleramt, den Bundes- können den Sammlungsbestand kennen. -

The Politics of Neoliberal Reforms in Africa: State and Civil Society in Cameroon Konings, P.J.J

The politics of neoliberal reforms in Africa: State and civil society in Cameroon Konings, P.J.J. Citation Konings, P. J. J. (2011). The politics of neoliberal reforms in Africa: State and civil society in Cameroon. Leiden: African Studies Centre and Langaa Publishers. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22175 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22175 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). The Politics of Neoliberal Reforms in Africa Langaa & African Studies Centre The Politics of Neoliberal Reforms in Africa State and Civil Society in Cameroon Piet Konings Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group PO Box 902 Mankon Bamenda North West Region Cameroon Phone +237 33 07 34 69 / 33 36 14 02 [email protected] http://www.langaa-rpcig.net www.africanbookscollective.com/publishers/langaa-rpcig African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] http://www.ascleiden.nl ISBN: © Langaa & African Studies Centre, 2011 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................ix List of Tables .........................................................................................xi Abbreviations....................................................................................... xiii Map of the Republic of Cameroon ...................................................... xvi 1 Contesting Neoliberal Reforms -

Performance, Relevance, Incantations, Poetry, Contemporary and Context

American Journal of Sociological Research 2017, 7(5): 123-132 DOI: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170705.01 The Artistic Performance and Social Significance of Nso Incantations Andrew T. Ngeh1,*, Ngeh Ernestilia Dzekem2 1University of Buea, Cameroon 2University of Bamenda, Cameroon Abstract This paper sets out to investigate whether the incantations performed by the people of Nso in the North West region of Cameroon are relevant in the contemporary society that is mostly characterized by enormous scientific and technological innovations. The study contends that “Lamnso” which is the language spoken by the Nso people of the North West region of Cameroon constitutes a reservoir and cultural quarry for Orature. The culture it houses is rich in oral literature even though it is being threatened by globalization, cultural imperialism, neo-colonialism and modernism. It is for this reason that, this study, considers the examination of Nso oral tradition as an integral global concern. In order to attain the objectives of this study, the ecocritical and sociological readings imposed themselves on these incantations. The study further argues that though most material of Orature comes from the past and was commonly seen to be rooted in the distant past, it can still be used to interpret contemporary and historical realities because it reviews the past, evaluates the present and anticipates the future. Raph Perry notes in the Foreword to African Culture: The Rhythms of Unity that “The past as embodied in contemporary adults is both the bed of reactionaries and springboard of innovations” (110). It is in this light that this study contends that the traditional society and the modern one are mutually inclusive entities with regard to African oral literature. -

Forest Community Integration and Collective Agency in Korup National Park

Forest Community Integration and Collective Agency in Korup National Park, Cameroon: Interactions with Forest Policies and the REDD+ Mechanism by Adam E. Flanery A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Geography College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida St. Petersburg Major Professor: Richard Mbatu, Ph.D. Rebecca Johns, Ph.D. Dona Stewart, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 1, 2016 Keywords: Community Forestry, Forest Conservation, Agro-industry, Africa, Institutional Analysis, Political Ecology Copyright © 2016, Adam E. Flanery Acknowledgements I’m extremely grateful to my thesis advisor, Dr. Richard Mbatu, for his guidance, and funding through his university start-up grant, without which the research could not have taken place. Dr. Mbatu’s skills conducting fieldwork in rural Africa, and his connections with people in the Korup area and professionals in Yaoundé were also essential. I’m indebted to the generosity of his family, many of whom graciously provided lodging and meals during the trip. I deeply appreciate the assistance of the other two members of my thesis committee, Dr. Dona Stewart and Dr. Rebecca Johns. They have given invaluable feedback and direction, as well as support and personal advice for navigating graduate school. My gratitude goes out to all the participants in the study, who volunteered their time and patience to take part. I would also like to extend my thanks to Chief Ekokola of Esukutan Village for his help in conducting the fieldwork, and the hospitality of his family. Finally, I appreciate the support and encouragement of my parents. -

Report on the Second Cycle of Periodic Reporting in the Africa Region

World Heritage 35 COM Limited Distribution WHC-11/35.COM/10A Paris, 27 May 2011 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-fifth Session Paris 19 – 29 June 2011 Item 10A of the Provisional Agenda: Report on the Second Cycle of Periodic Reporting in the Africa region SUMMARY This document presents a synthesis and analysis of the Second Cycle of Periodic Reporting in Africa submitted in accordance with Decision 33 COM 11.C. It provides information on the data provided by States Parties in the Africa region on the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention at the national level (Section I), as well as the data provided on the World Heritage properties (Section II). This document is presented as follows: Executive Summary Introduction Chapter 1: Implementation of the World Heritage Convention in Africa Region States Parties (Results of Section I) Chapter 2: African World Heritage Properties (Results of Section II) Chapter 3: Capacity Building Chapter 4: African States Parties Recommendations to the Committee Annexes: Quantitative analysis results for Section I and Section II of the Questionnaire; List of key resource persons, World Heritage properties and site managers; Draft Capacity Building Strategy proposed by the regional training institutions. Draft Decision: 35 COM 10A, see Chapter 4, page 50 Second Cycle of Periodic Reporting in the Africa Region WHC-11/35.COM/10A TABLE -

Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects

Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects Edited by Albertina Nugteren Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects Special Issue Editor Albertina Nugteren MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Albertina Nugteren Tilburg University The Netherlands Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/Ritual) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-752-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-753-7 (PDF) c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects” ......................... ix Albertina Nugteren Introduction to the Special Issue ‘Religion, Ritual, and Ritualistic Objects’ Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 163, doi:10.3390/rel10030163 .................. -

Policy Alternatives for the Cameroon Conflicts with Views on Abolishing the Federation Christmas Atem Ebini Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Policy Alternatives for the Cameroon Conflicts with Views on Abolishing the Federation Christmas Atem Ebini Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Christmas A. Ebini has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Augusto Ferreros, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Mi Young Lee, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. James Mosko, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty The Office of the Provost Walden University 2019 Abstract Policy Alternatives for the Cameroon Conflicts with Views on Abolishing the Federation by Christmas A. Ebini MSW, 2005 Howard University, Washington, DC MMFT, 2001Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX MS, 1995 Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX MBA, 1995 Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX BBA, 1985, Harding University, Searcy, AK AA, 1984 Ohio Valley College, Parkersburg, WV Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration: Homeland Security and Administration Walden University September 2019 Abstract The violent conflicts in the Northwest and Southwest provinces of Cameroon (Southern Cameroons) have obtained national and international attention. -

BSF Campus, Relationships Or Learn to Participate in Civic Life

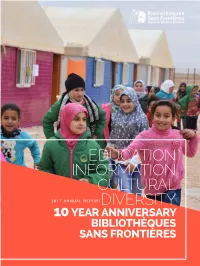

EDUCATION INFORMATION CULTURAL 2017 ANNUAL REPORTDIVERSITY 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY BIBLIOTHÈQUES SANS FRONTIÈRES Table of Contents Libraries Without Borders (BSF): 10 year anniversary A WORD FROM OUR CHAIRMAN Patrick Weil - Page 5 AN INTERVIEW WITH OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Jérémy Lachal - Page 7 Overview Page 12 A 10-year Timeline Page 14 Our Tools Page 8 Map Page 24 10 YEARS OF ACTION Page 26 Emergency, post-conflict & peacebuilding Page 28 Education & cultural diversity Page 38 Entrepreneurship & social transformation Page 59 10 YEARS OF ADVOCACY Page 64 10 YEARS OF ACCOUNTABILITY Page 74 3 10 YEARS OF ACTION to include the intellectual needs of populations in need. Our second area of intervention is reinforcing the role of A Word from libraries as major actors in the fight against inequality and construction of democratic citizenship. Our third area of intervention is promoting social innovation and Our entrepreneurship in library spaces to create economically sustainable models with a strong social impact and Chairman incubators for social projects. Patrick Weil « For 10 years we have For a decade, Bibliothèques Sans Frontières has worked defended the idea that tirelessly to reinforce the autonomy of the most vulnerable people in the world by improving their access to cultural access to information, education, and culture. Since resources is a fundamental our founding, we have defended the notion that culture is a fundamental human right that promotes autonomy, right as well as a strong critical thought, and democratic civic dialogue. Libraries are epicenters for the material forms that culture takes. promoting agent As such, they are critical to advancing equality in a of freedom, critical thougth world where access to information and education (or their absence) serve as markers of inequality.