John Wayne and Forrest Gump, Strange Bedfellows: the Influential and Reflective Media Loop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

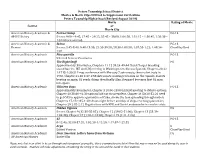

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

VVMF Education Guide

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL War will always have impacts on society and culture. Within the realm of popular culture, popular films released after the end of the Vietnam War reflect a range of public perspectives about the conflict. DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of popular films that depict the Vietnam War, era, and veterans, as well as more How Does Film recent popular films that depict more recent wars. Students will examine the Reflect Perspectives perspectives of these films and how the range of perspectives was reflected in on War? broader society following the war. Download the Perspectives on War? Reflect Does Film How Accompanying Powerpoint Presentation for use in the classroom > PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 1 Films from Vietnam Ask students to create a list of movies they have seen that have a focus on the Vietnam War, era, or veterans (for a list, see: http://www.vvmf.org/teaching-vietnam). Ask each student to choose a favorite from the list and explain his/her reasoning for why it’s his/her favorite. If a student hasn’t see any—ask him or her to choose one to watch at home. For that movie, ask students to answer the following questions: • What issues are depicted in the movie? • Would you say that the movie takes a position on the war? What evidence supports your answer? • What part or parts of the movie struck you? Why? • What do you think someone who had no background on the Vietnam War or era would take away about it from this movie? PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 2 Vietnam in Media Ask students to poll 10 of their siblings, friends, or even parents: What are the top two NOTE TO sources from which they have any understanding of the TEACHER Vietnam War and era? Place a tally mark beside each response. -

The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Interviews Stone on Stone Between 2010 and 2014 we interviewed Oliver Stone on a number of occasions, either personally or in correspondence by email. He was always ready to engage with us, quite literally. Stone thrives on the cut- and- thrust of debate about his films, about himself and per- ceptions of him that have adorned media outlets around the world throughout his career – and, of course, about the state of America. What follows are transcripts from some of those interviews, with- out redaction. Stone is always at his most fascinating when a ques- tion leads him down a line of theory or thinking that can expound on almost any topic to do with his films, or with the issues in the world at large. Here, that line of thinking appears on the page as he spoke, and gives credence to the notion of a filmmaker who, whether loved or loathed, admired or admonished, is always ready to fight his corner and battle for what he believes is a worthwhile, even noble, cause. Oliver Stone’s career has been defined by battle and the will to overcome criticism and or adversity. The following reflections demonstrate why he remains the most talked about, and combative, filmmaker of his generation. Interview with Oliver Stone, 19 January 2010 In relation to the Classification and Ratings Administration Interviewer: How do you see the issue of cinematic censorship? Oliver Stone: The ratings thing is very much a limited game. If you talk to Joan Graves, you’ll get the facts. The rules are the rules. -

Mustang Daily, April 15, 1970

. '• ohlvpc Kennedy vows EOP support by FRANK ALDERETE of. the Mexican American; rTrviouHiyIKuaHAUAUi •kAutMDoui me only--- s— way— —a in 196*70 kicked te Staff Wrttar monetary and educational x person- could get himself Into a MO,000. SAC State students gave Noting that “success of the deprivations In the case of other college was to excell In athletics. $90,000 which enabled 07 more program la related to financial minorities such as Afro- "But now, Kennedy said, "we students to enroll In classes, support,Prei. Robert E. American and American Indian. can admit 2 per cent of minority Kennedy said that "he would Kennedy announced h^ ad The ability of an Individual to „ groups Into our campus. Now like to see the EOP program vocacy for the support of the rise up out of the ghetto quagmire they have a chance." expand." but that he would Economic Opportunity Program and to make himself a success is Tomorrow students will vote In rather see "a good program for a In an Interview yeeterday. a problem that has faced the a special election to determine few students than a mediocre one The problem of a lack of underprlvillged for years. whether or not ASI funds could be for a lot." motivation of an Individual Kennedy said that the "EOP used to support the EOP. Kennedy said that the program toward echolaetlc achievement la offers a minority lndivudual the Currently eight state colleges use oould and should utilise any funds ceueed by aeveral reasons— chance to make himself good and ASI funds to support their It could get. -

Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War

International Feminist Journal of Politics ISSN: 1461-6742 (Print) 1468-4470 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfjp20 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War Joanna Tidy To cite this article: Joanna Tidy (2015) Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17:3, 454-472, DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 Published online: 02 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 248 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfjp20 Download by: [University of Massachusetts] Date: 28 June 2016, At: 13:24 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War JOANNA TIDY School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS), University of Bristol, UK Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This article considers the gendered dynamics of the contemporary military peace move- ment in the United States, interrogating the way in which masculine privilege produces hierarchies within experiences, truth claims and dissenting subjecthoods. The analysis focuses on a text of the movement, the 2007 documentary -

Public Politics/Personal Authenticity

PUBLIC POLITICS/PERSONAL AUTHENTICITY: A TALE OF TWO SIXTIES IN HOLLYWOOD CINEMA, 1986- 1994 Oliver Gruner Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies August, 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One “The Enemy was in US”: Platoon and Sixties Commemoration 62 Platoon in Production, 1976-1982 65 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Platoon from Script to Screen 73 From Vietnam to the Sixties: Promotion and Reception 88 Conclusion 101 Chapter Two “There are a lot of things about me that aren’t what you thought”: Dirty Dancing and Women’s Liberation 103 Dirty Dancing in Production, 1980-1987 106 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Dirty Dancing from Script to Screen 114 “Have the Time of Your Life”: Promotion and Reception 131 Conclusion 144 Chapter Three Bad Sixties/ Good Sixties: JFK and the Sixties Generation 146 Lost Innocence/Lost Ignorance: Kennedy Commemoration and the Sixties 149 Innocence Lost: Adaptation and Script Development, 1988-1991 155 In Search of Authenticity: JFK ’s “Good Sixties” 164 Through the Looking Glass: Promotion and Reception 173 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four “Out of the Prison of Your Mind”: Framing Malcolm X 188 A Civil Rights Sixties 191 A Change -

Hanks, Spielberg Tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood Poll

Hanks, Spielberg tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood poll June 8, 2011 By U.S. Army Europe Public Affairs HEIDELBERG, Germany -- “Band of Brothers” narrowly edged “Saving Private Ryan” in a two-week U.S. Army Europe Web poll asking the public to select their five favorite Related Links films portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. Poll Results The final tally for the top spot was 128 votes to 126, revealing the powerful appeal Tom U.S. Army Europe Facebook Hanks and Steven Spielberg hold among poll participants in detailing the experiences of U.S. Army Europe Twitter WWII veterans. U.S. Army Europe YouTube The two movies were both the result of collaborations by the Hollywood A-listers. U.S. Army Europe Flickr Rounding out the top five was “The Longest Day,” a 1962 drama starring John Wayne about the events of D-Day; “Patton,” directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1970 and starring George C. Scott as the famed American general; and “A Bridge Too Far,” a 1977 film starring Sean Connery about the failed Operation Market- Garden. The poll received a total of 814 votes and was based on the realism, entertainment value and overall quality of 20 movies featuring the U.S. Army in Europe. Some of Hollywood's biggest stars throughout history - Elvis, Clint Eastwood, Gary Cooper, Bill Murray, Gene Hackman – have all taken turns on the big screen portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. But to participants of the U.S. Army Europe poll, it was the lesser-known “Band of Brothers” in Easy Company who were most endearing. -

The Hobbit the Desolation of Smaug the Quest for Erbor / the Forest River / the Hunters / Beyond the Forest

The Hobbit The Desolation Of Smaug The Quest For Erbor / The Forest River / The Hunters / Beyond The Forest Brass Band Arr.: Jirka Kadlec Adapt.: Bertrand Moren Howard Shore EMR 9842 st + 1 Full Score 2 1 B Trombone nd + 1 E Cornet 2 2 B Trombone + 5 Solo B Cornet 1 B Bass Trombone 1 Repiano Cornet 2 Euphonium nd 3 2 B Cornet 3 E Bass rd 3 3 B Cornet 3 B Bass 1 B Flugelhorn 1 Timpani st 2 Solo E Horn 1 1 Percussion (Tubular Bells / Glockenspiel) st nd 2 1 E Horn 1 2 Percussion (Suspended Cymbal) nd rd 2 2 E Horn 1 3 Percussion (Triangle / Drum Set) st 2 1 B Baritone nd 2 2 B Baritone Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ! www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 ! CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 ! Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 ! E-Mail : [email protected] ! www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Cinemagic 47 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 The Incredibles (Giacchino) 6’00 EMR 12185 EMR 9667 2 Concerto De L’Adieu (Delerue) 9’57 EMR 12277 EMR 9837 3 Tombstone (Broughton) 7’37 EMR 12245 EMR 9838 4 Jaws: The Revenge (Small) 3’48 EMR 12191 EMR 9839 5 The Croods (Silvestri) 4’38 EMR 12258 EMR 9840 6 Rise Of The Guardians (Desplat) 7’40 EMR 12234 EMR 9763 7 The Karate Kid (Horner) 9’00 EMR 12238 EMR 9841 8 The Hobbit (The Desolation Of Smaug) (Shore) 4’17 EMR 12261 EMR 9842 Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel. -

Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2001 Strange Bedfellows: Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927 Sarah L. Trembanis College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Trembanis, Sarah L., "Strange Bedfellows: Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927" (2001). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624397. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-eg2s-rc14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRANGE BEDFELLOWS- Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927. A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Sarah L. Trembanis 2001 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sarah L. Trembanis Approved, August 2001 (?L Ub Kimbe$y L. Phillips 'James McCord TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments iv Abstract v Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Dealing with “Mongrel Virginians” 25 Chapter 2: An Unlikely Alliance 47 Conclusion 61 Appendix One: An Act to Preserve Racial Integrity 64 Appendix Two: Model Eugenical Sterilization Law 67 Bibliography 74 Vita 81 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Kimberly Phillips, for all of her invaluable suggestions and assistance. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Holy Fools, Secular Saints, and Illiterate Saviors in American Literature and Popular Culture

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 5 (2003) Issue 3 Article 4 Holy Fools, Secular Saints, and Illiterate Saviors in American Literature and Popular Culture Dana Heller Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Heller, Dana. "Holy Fools, Secular Saints, and Illiterate Saviors in American Literature and Popular Culture." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.3 (2003): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1193> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Ordinary Heroes: Depictions of Masculinity in World War II Film a Thesis Submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in Pa

Ordinary Heroes: Depictions of Masculinity in World War II Film A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Robert M. Dunlap May 2007 Oxford, Ohio Abstract Much work has been done investigating the historical accuracy of World War II film, but no work has been done using these films to explore social values. From a mixed film studies and historical perspective, this essay investigates movie images of American soldiers in the European Theater of Operations to analyze changing perceptions of masculinity. An examination of ten films chronologically shows a distinct change from the post-war period to the present in the depiction of American soldiers. Masculinity undergoes a marked change from the film Battleground (1949) to Band of Brothers (2001). These changes coincide with monumental shifts in American culture. Events such as the loss of the Vietnam War dramatically changed perceptions of the Second World War and the men who fought during that time period. The United States had to deal with a loss of masculinity that came with their defeat in Vietnam and that shift is reflected in these films. The soldiers depicted become more skeptical of their leadership and become more uncertain of themselves while simultaneously appearing more emotional. Over time, realistic images became acceptable and, in fact, celebrated as truthful while no less masculine. In more recent years, there is a return to the heroism of the World War II generation, with an added emotionality and dimensionality. Films reveal not only the popular opinions of the men who fought and reflect on the validity of the war, but also show contemporary views of masculinity and warfare.