The Vietnam War in the American Mind, 1975-1985 Mark W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

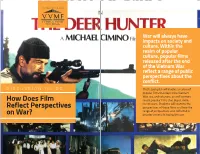

VVMF Education Guide

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL War will always have impacts on society and culture. Within the realm of popular culture, popular films released after the end of the Vietnam War reflect a range of public perspectives about the conflict. DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of popular films that depict the Vietnam War, era, and veterans, as well as more How Does Film recent popular films that depict more recent wars. Students will examine the Reflect Perspectives perspectives of these films and how the range of perspectives was reflected in on War? broader society following the war. Download the Perspectives on War? Reflect Does Film How Accompanying Powerpoint Presentation for use in the classroom > PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 1 Films from Vietnam Ask students to create a list of movies they have seen that have a focus on the Vietnam War, era, or veterans (for a list, see: http://www.vvmf.org/teaching-vietnam). Ask each student to choose a favorite from the list and explain his/her reasoning for why it’s his/her favorite. If a student hasn’t see any—ask him or her to choose one to watch at home. For that movie, ask students to answer the following questions: • What issues are depicted in the movie? • Would you say that the movie takes a position on the war? What evidence supports your answer? • What part or parts of the movie struck you? Why? • What do you think someone who had no background on the Vietnam War or era would take away about it from this movie? PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 2 Vietnam in Media Ask students to poll 10 of their siblings, friends, or even parents: What are the top two NOTE TO sources from which they have any understanding of the TEACHER Vietnam War and era? Place a tally mark beside each response. -

The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Interviews Stone on Stone Between 2010 and 2014 we interviewed Oliver Stone on a number of occasions, either personally or in correspondence by email. He was always ready to engage with us, quite literally. Stone thrives on the cut- and- thrust of debate about his films, about himself and per- ceptions of him that have adorned media outlets around the world throughout his career – and, of course, about the state of America. What follows are transcripts from some of those interviews, with- out redaction. Stone is always at his most fascinating when a ques- tion leads him down a line of theory or thinking that can expound on almost any topic to do with his films, or with the issues in the world at large. Here, that line of thinking appears on the page as he spoke, and gives credence to the notion of a filmmaker who, whether loved or loathed, admired or admonished, is always ready to fight his corner and battle for what he believes is a worthwhile, even noble, cause. Oliver Stone’s career has been defined by battle and the will to overcome criticism and or adversity. The following reflections demonstrate why he remains the most talked about, and combative, filmmaker of his generation. Interview with Oliver Stone, 19 January 2010 In relation to the Classification and Ratings Administration Interviewer: How do you see the issue of cinematic censorship? Oliver Stone: The ratings thing is very much a limited game. If you talk to Joan Graves, you’ll get the facts. The rules are the rules. -

The Global Visual Memory a Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs

The Global Visual Memory A Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs Het Mondiaal Visueel Geheugen Een studie naar de herkenning en interpretatie van iconische en historische foto’s (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 19 juni 2019 des middags te 2.30 uur door Rutger van der Hoeven geboren op 4 juni 1974 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. dr. J. Van Eijnatten Table of Contents Abstract 2 Preface 3 Introduction 5 Objectives 8 Visual History 9 Collective Memory 13 Photographs as vehicles of cultural memory 18 Dissertation structure 19 Chapter 1. History, Memory and Photography 21 1.1 Starting Points: Problems in Academic Literature on History, Memory and Photography 21 1.2 The Memory Function of Historical Photographs 28 1.3 Iconic Photographs 35 Chapter 2. The Global Visual Memory: An International Survey 50 2.1 Research Objectives 50 2.2 Selection 53 2.3 Survey Questions 57 2.4 The Photographs 59 Chapter 3. The Global Visual Memory Survey: A Quantitative Analysis 101 3.1 The Dataset 101 3.2 The Global Visual Memory: A Proven Reality 105 3.3 The Recognition of Iconic and Historical Photographs: General Conclusions 110 3.4 Conclusions About Age, Nationality, and Other Demographic Factors 119 3.5 Emotional Impact of Iconic and Historical Photographs 131 3.6 Rating the Importance of Iconic and Historical Photographs 140 3.7 Combined statistics 145 Chapter 4. -

Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War

International Feminist Journal of Politics ISSN: 1461-6742 (Print) 1468-4470 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfjp20 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War Joanna Tidy To cite this article: Joanna Tidy (2015) Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17:3, 454-472, DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 Published online: 02 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 248 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfjp20 Download by: [University of Massachusetts] Date: 28 June 2016, At: 13:24 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War JOANNA TIDY School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS), University of Bristol, UK Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This article considers the gendered dynamics of the contemporary military peace move- ment in the United States, interrogating the way in which masculine privilege produces hierarchies within experiences, truth claims and dissenting subjecthoods. The analysis focuses on a text of the movement, the 2007 documentary -

Newsletter Still Doesn't Have Any Reporting on Direct Queries and Submissions To: Recent Developments in U.S

N ewsletter NoVEMbER, 1991 VolUME 5 NuMbER 5 SpEciAl JournaL Issue In This Issue................................................................ 2 The Speed of DAnksess ancI "CrazecJ V ets on tHe oorstep rama e o s e PublJshER's S tatement, by Ka U TaL .............................5 D D ," by DAvId J. D R ...............40 REMF Books, by DAvid WHLs o n .............................. 45 A nnouncements, Notices, & Re p o r t s ......................... 4 eter C ortez In DarIen, by ALan FarreU ........................... 22 PoETRy, by P D ssy............................................4 4 FIctIon: Hie Romance of Vietnam, VoIces fROM tHe Past: TTie SearcTi foR Hanoi HannaK by RENNy ChRlsTophER...................................... 24 by Don NortTi ...................................................44 A FiREbAlL In tBe Nlqlrr, by WHUam M. KiNq...........25 H ollyw ood CoNfidENTlAl: 1, b y FREd GARdNER........ 50 Topics foR VJetnamese-U.S. C ooperation, PoETRy, by DennIs FRiTziNqER................................... 57 by Tran Qoock VuoNq....................................... 27 Ths A ll CWnese M ercenary BAskETbAll Tournament, Science FIctIon: This TIme It's War, by PauI OLim a r t ................................................ 57 by ALascIaIr SpARk.............................................29 (Not Much of a) War Story, by Norman LanquIst ...59 M y Last War, by Ernest Spen cer ............................50 Poetry, by Norman LanquIs t ...................................60 M etaphor ancI War, by GEORqE LAkoff....................52 A notBer -

Public Politics/Personal Authenticity

PUBLIC POLITICS/PERSONAL AUTHENTICITY: A TALE OF TWO SIXTIES IN HOLLYWOOD CINEMA, 1986- 1994 Oliver Gruner Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies August, 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One “The Enemy was in US”: Platoon and Sixties Commemoration 62 Platoon in Production, 1976-1982 65 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Platoon from Script to Screen 73 From Vietnam to the Sixties: Promotion and Reception 88 Conclusion 101 Chapter Two “There are a lot of things about me that aren’t what you thought”: Dirty Dancing and Women’s Liberation 103 Dirty Dancing in Production, 1980-1987 106 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Dirty Dancing from Script to Screen 114 “Have the Time of Your Life”: Promotion and Reception 131 Conclusion 144 Chapter Three Bad Sixties/ Good Sixties: JFK and the Sixties Generation 146 Lost Innocence/Lost Ignorance: Kennedy Commemoration and the Sixties 149 Innocence Lost: Adaptation and Script Development, 1988-1991 155 In Search of Authenticity: JFK ’s “Good Sixties” 164 Through the Looking Glass: Promotion and Reception 173 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four “Out of the Prison of Your Mind”: Framing Malcolm X 188 A Civil Rights Sixties 191 A Change -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq

'The Best Covered War in History': Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq by Andrew J. McLaughlin A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Andrew J. McLaughlin 2017 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Marco Rimanelli Professor, St. Leo University Supervisor(s) Andrew Hunt Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Jasmin Habib Associate Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Roger Sarty Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University Internal-external Member Brian Orend Professor, University of Waterloo ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This study examines combat operations from the 2003 invasion of Iraq War from the “ground up.” It utilizes unique first-person accounts that offer insights into the realities of modern warfare which include effects on soldiers, the local population, and journalists who were tasked with reporting on the action. It affirms the value of media embedding to the historian, as hundreds of journalists witnessed major combat operations firsthand. This line of argument stands in stark contrast to other academic assessments of the embedding program, which have criticized it by claiming media bias and military censorship. Here, an examination of the cultural and social dynamics of an army at war provides agency to soldiers, combat reporters, and innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. -

Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Oral History Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8sb4b6f Online items available Guide to the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Oral History Collection Sean Heyliger African American Museum & Library at Oakland 659 14th Street Oakland, California 94612 Phone: (510) 637-0198 Fax: (510) 637-0204 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.oaklandlibrary.org/locations/african-american-museum-library-oakland © 2013 African American Museum & Library at Oakland. All rights reserved. Guide to the Robert C. Maynard MS 192 1 Institute for Journalism Education Oral History Collection Guide to the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Oral History Collection Collection number: MS 192 African American Museum & Library at Oakland Oakland, California Processed by: Sean Heyliger Date Completed: 11/06/2015 Encoded by: Sean Heyliger © 2013 African American Museum & Library at Oakland. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Oral History collection Dates: 2001 Collection number: MS 192 Creator: Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Collection Size: 1.5 linear feet(2 boxes) Repository: African American Museum & Library at Oakland (Oakland, Calif.) Oakland, CA 94612 Abstract: The Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Oral History Collection consists of 29 oral history interviews conducted in 2001 by Earl Caldwell with prominent black journalists that began their careers during the 1960s-1970s. A majority of the interviewees worked at -

And Where He Did

Vol. 2 No. 9 October 1992 $4.00 and where he did Volume 2 Number 9 I:URI:-KA STRI:-eT October 1992 A m agazine of public affairs, the arts and theology 21 CoNTENTS TOPGUN Michael McGirr reports on gun laws and the calls for capital punishment in the 4 Philippines. COMMENT In this year of elections we are only as good 22 as our choices, says Peter Steele. Andrew DON'T KISS ME, HARDY Hamilton looks at the Columbus quin James Griffin concludes his series on the centary, and decides that the past must be Wren-Evatt letters. owned as well as owned up to (pS). 6 25 ORIENTATIONS LETTERS Peter Pierce and Robin Gerster take their pens to Shanghai and Saigon; Emmanuel 7 Santos and Hwa Goh take their cameras to COMMISSIONS AND OMISSIONS Tianjin. ICAC chief Ian Temby Margaret Simons talks to Australia's top speaks for himself: p 7 crime-busters. 34 11 BOOKS AND ARTS Cover photo: A member of Was the oldest part of the Pentateuch CAPITAL LETTER the Tianjing city planning office written by a woman? Kevin Hart reviews in Jei Fang Bei Road, three books by Harold Bloom, who thinks the 'Wall Street' of Tianjin. 12 it was; Robert Murray sizes up Columbus BLINDED BY THE LIGHT and colonialism (p38 ). Cover photo and photos pp25, 29 and 30 Bruce Williams visits the Columbus light by Emmanuel Santos; house in Santo Domingo, and wonders who Photo p27 by Hwa Goh; will be enlightened. 40 Photos p12 by Belinda Bain; FLASH IN THE PAN Photo p41 by Bill Thomas; 15 Reviews of the films Patriot Games Cartoons pp6, 36 and 3 7 by Dean Moore; Zentropa, Edward II, and Deadly. -

POF 22 Interviewee: Stanley Karnow Interviewer: Michael Gannon Date

POF 22 Interviewee: Stanley Karnow Interviewer: Michael Gannon Date: G: Hello, I am Mike Gannon [Michael V. Gannon, retired Distinguished Service Professor of History, former director of Early contact Period Studies, CLAS] and this is Conversation. A landmark in the production of television documentaries has been the thirteen part series called "Vietnam: A Television History." It was shown on PBS last year and is being repeated on that network this year. It is thorough because it is based on sound scholarship. It is comprehensive because it uses film and tape from this country, from France, and from North Vietnam. The series includes interviews with many of the principals in that very difficult conflict. The script was written by Stanley Karnow, and while he wrote the script, he authored a book which has a similar title -- Vietnam: A History. Stanley Karnow, welcome to Conversation. K: Thank you. G: Welcome to the campus of the University of Florida. That was quite an achievement to have developed with one hand a thirteen part television series and with the other hand a very sound and impressive book. How long did it take you to do this? K: The television series was about six or seven years in the making; that is, we conceived of the idea back in 1977. It being public television, we had to raise money, which was very difficult. At the time that we were thinking about the series, it occurred to me that a companion book would be a good idea. Television is a medium of drama, of impressions, but it is not exactly a medium for explanation and for interpretation. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 11:21:08PM Via Free Access 100 the Politics of Memory

5 The articulation of memory and desire: from Vietnam to the war in the Persian Gulf John Storey In this chapter I want to explore, within a context of culture and power, the complex relations between memory and desire.1 More specifically, I want to connect 1980s Hollywood representations of America’s war in Vietnam (what I will call ‘Hollywood’s Vietnam’) with George Bush’s campaign, in late 1990 and early 1991, to win support for US involvement in what became the Gulf War. My argu- ment is that Hollywood produced a particular ‘regime of truth’2 about America’s war in Vietnam and that this body of ‘knowledge’ was ‘articulated’3 by George Bush as an enabling ‘memory’ in the build up to the Gulf War. Vietnam revisionism and the Gulf War In the weeks leading up to the Gulf War, Newsweek featured a cover showing a photograph of a serious-looking George Bush. Above the photograph was the banner headline, ‘This will not be another Viet- nam’. The headline was taken from a speech made by Bush in which he said, ‘In our country, I know that there are fears of another Viet- nam. Let me assure you . this will not be another Vietnam.’4 In another speech, Bush again assured his American audience that, ‘This will not be another Vietnam . Our troops will have the best possi- ble support in the entire world. They will not be asked to fight with one hand tied behind their backs.’5 Bush was seeking to put to rest a spectre that had come to haunt America’s political and military self- image, what Richard Nixon and others had called the ‘Vietnam Syn- drome’.6 The debate over American foreign policy had, according to Nixon, been ‘grotesquely distorted’ by an unwillingness ‘to use power to defend national interests’.7 Fear of another Vietnam, had made America ‘ashamed of .