The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Januar Februar

brezpla~ni izvod po{tnina pla~ana pri po{ti 1106 ljubljana kinote~nik 2011 2012 januar-februar Rainer Werner Fassbinder retrospektiva ostanite {e naprej z nami Televizijskim ogledom in uvidom sledi {e ob{irnej{a, po skoraj dvajsetletnem "Televizija! Vzgojiteljica, mati, ljubica." doma~em zamolku toliko glasnej{a retrospektiva nem{kega scenarista, dramatika, Homer Simpson igralca, producenta in re`iserja Rainerja Wernerja Fassbinderja, ki bo prinesla "Za film bi rad pomenil to, kar Shakespeare pomeni za gledali{~e, Marx za {tirideset projekcij dvajsetih filmov plus – kot je pri ve~jih retrospektivah spet v politiko in Freud za psihologijo: nekdo, za komer ni~ ne ostane isto." navadi – zajeten kinote~ni katalog, posve~en avtorju. Kdor je Fassbinderja `e Rainer Werner Fassbinder gledal, ga bo pri{el pogledat spet (retrospektiva, mimogrede, prina{a kup , letnik XII, {tevilka 5–6, januar-februar 2012 naslovov, ki v Sloveniji {e nikoli niso bili predvajani na velikem platnu). Kdor Kaj imata skupnega televizija in Rainer Werner Fassbinder razen tega, da je prva Fassbinderja {e ni gledal, pa ima v Kinoteki rezerviran abonma ne samo pri radikalno posegla v tok navad in obna{anja 20. stoletja, drugi pa ni~ manj predmetu filma, pa~ pa tudi na podro~ju ob~utljivih to~k evropske zgodovine radikalno v tok filmske zgodovine istega stoletja? Poleg dejstva, da je Fassbinder dvajsetega stoletja, brezkompromisnega politi~nega udejstvovanja, eti~nega pribli`no tretjino svojega enormnega opusa posnel prav za televizijo, ju tokrat anga`maja in njemu pripadajo~ega dogodka ljubezni. dru`i tudi skupen nastop v januarsko-februarskem programu Kinoteke. Retrospektiva se bo iz januarja prelila v februar, ta pa se sklepa z mnogo manj ali Tega na samem pragu novega leta odpiramo z ob{irno, tematsko retrospektivo, prav ni~ "kanoni~no", a zato ni~ manj "pou~no" retrospektivo, ki bo predstavila ki smo jo poimenovali Ekrani na platnu in v sklopu katere raziskujemo, na kak{ne pet filmov Reze Mirkarimija, mlaj{ega cineasta iranskega rodu. -

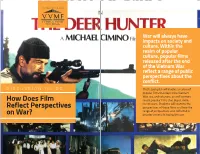

VVMF Education Guide

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL War will always have impacts on society and culture. Within the realm of popular culture, popular films released after the end of the Vietnam War reflect a range of public perspectives about the conflict. DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of popular films that depict the Vietnam War, era, and veterans, as well as more How Does Film recent popular films that depict more recent wars. Students will examine the Reflect Perspectives perspectives of these films and how the range of perspectives was reflected in on War? broader society following the war. Download the Perspectives on War? Reflect Does Film How Accompanying Powerpoint Presentation for use in the classroom > PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 1 Films from Vietnam Ask students to create a list of movies they have seen that have a focus on the Vietnam War, era, or veterans (for a list, see: http://www.vvmf.org/teaching-vietnam). Ask each student to choose a favorite from the list and explain his/her reasoning for why it’s his/her favorite. If a student hasn’t see any—ask him or her to choose one to watch at home. For that movie, ask students to answer the following questions: • What issues are depicted in the movie? • Would you say that the movie takes a position on the war? What evidence supports your answer? • What part or parts of the movie struck you? Why? • What do you think someone who had no background on the Vietnam War or era would take away about it from this movie? PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 2 Vietnam in Media Ask students to poll 10 of their siblings, friends, or even parents: What are the top two NOTE TO sources from which they have any understanding of the TEACHER Vietnam War and era? Place a tally mark beside each response. -

Basketball Diaries, Natural Born Killers and School Shootings: Should There Be Limits on Speech Which Triggers Copycat Violence

Denver Law Review Volume 77 Issue 4 Symposium - Law and Policy on Youth Article 8 Violence January 2021 Basketball Diaries, Natural Born Killers and School Shootings: Should There Be Limits on Speech Which Triggers Copycat Violence Juliet Dee Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Juliet Dee, Basketball Diaries, Natural Born Killers and School Shootings: Should There Be Limits on Speech Which Triggers Copycat Violence, 77 Denv. U. L. Rev. 713 2000). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. BASKETBALL DIARIES, NATURAL BORN KILLERS AND SCHOOL SHOOTINGS: SHOULD THERE BE LIMITS ON SPEECH WHICH TRIGGERS COPYCAT VIOLENCE? JULIET DEE* I. INTRODUCTION During the past five years, parents who send their children to school in the morning have had to face the grim possibility, however remote, that their children might be shot and killed by a classmate during the school day. ABC News provides a list of school shootings between 1996 and the present', which is as follows: February 19, 1997: 16 year-old Evan Ramsey opens fire with a shot- gun in a common area at the Bethel, Alaska, high school, killing the principal and a student and wounding two others. He is sentenced to two 99-year terms. October 1, 1997: A 16 year-old boy in Pearl, Mississippi is accused of killing his mother, then going to Pearl High School, killing two students including his ex-girifriend and wounding seven others. -

Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War

International Feminist Journal of Politics ISSN: 1461-6742 (Print) 1468-4470 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfjp20 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War Joanna Tidy To cite this article: Joanna Tidy (2015) Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17:3, 454-472, DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 Published online: 02 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 248 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfjp20 Download by: [University of Massachusetts] Date: 28 June 2016, At: 13:24 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War JOANNA TIDY School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS), University of Bristol, UK Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This article considers the gendered dynamics of the contemporary military peace move- ment in the United States, interrogating the way in which masculine privilege produces hierarchies within experiences, truth claims and dissenting subjecthoods. The analysis focuses on a text of the movement, the 2007 documentary -

PAM WISE, A.C.E. EDITOR Local 700 Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences

PAM WISE, A.C.E. EDITOR Local 700 Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences FEATURES THE LAST SONG (Short) Duly Noted Inc./HBO Sponsored Prod: Effie Brown Dir: Sasie Sealy SHOULD’VE BEEN ROMEO Angel Baby Ent. Prod: Gregory Segal, Paul Ben-Victor Dir: Marc Bennett EVERY DAY Ambush Ent. Prod: Miranda Bailey, Amanda Marshall Dir: Richard Levine Cast: Helen Hunt, Liev Schreiber, Brian Dennehy, Eddie Izzard, Carla Gugino *Official Selection: Tribeca Film Festival 2010, Seattle Film Festival 2010 THEN SHE FOUND ME Killer Films Prod: Pamela Koffler, Christine Vachon Dir: Helen Hunt Cast: Helen Hunt, Bette Midler, Colin Firth, Matthew Broderick *Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival 2007 *Audience Award, Palm Springs International Film Festival 2008 DARK MATTER Myriad Pics. Prod: Mary Salter, Janet Yang Dir: Chen Shi-Zheng Cast: Liu Ye, Meryl Streep, Bill Irwin, Blair Brown *Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize, Sundance Film Festival 2007 TRANSAMERICA IFC Films Prod: Rene Bastian, Linda Moran Dir: Duncan Tucker Cast: Felicity Huffman, Kevin Zegers *Nominated for Best Actress, Academy Awards 2006 SECRETARY Lions Gate Prod: Andrew Fierberg, Amy Hobby Dir: Steven Shainberg Cast: Maggie Gyllenhaal, James Spader *Nominated for Best Feature, Independent Spirit Awards 2003 *Special Jury Prize, Sundance Film Festival 2002 THE QUICKIE Pandora Filmproduktion Prod: Karl Baumgartner Dir: Sergei Bodrov Cast: Vladimir Moshkov, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Dean Stockwell, Lesley Ann Warren, Henry Thomas *Official Selection Moscow International -

The Aesthetics of Death, Youth, and the Road: the Violent Road Film In

• The Aesthetics of Death, Youth, and the Road: The Violent Road Film in Popular Culture Heather E. McDiarmid Graduate Program ir. Communications McGill University Montreal, Quebec Julv, 1996 A thesis submitted ta the Facultv ofGraduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of thed~ofMuterofArts • © 1996 Heather E. McDiarmid NaltOOal Llbrary Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Ganada duGanada ACqUISllions and Direction des acqUlsltlOtlS et Blbliographlc serllCes Branch des serviCes bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Well'"Q1On Ottawa. Onlano Ottawa cOnt.no) K1AON4 K'AQN4 The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé u~e licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irrévocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou hisjher thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires dé cette thèse à la disposition des personnes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'a!Jteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in hisjher thesis. droit d'auteur qui protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from il may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou hisjher permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation. ISBN 0-612-19906-1 Canada • Abstract The "roadkill" films are part of a sub-genre of the more popular road film genre. -

Reframe and Imdbpro Announce New Collaboration to Recognize Standout Gender-Balanced Film and TV Projects

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: June 7, 2018 For Sundance Institute: Jenelle Scott 310.360.1972 [email protected] For Women In Film: Catherine Olim 310.967.7242 [email protected] For IMDbPro: Casey De La Rosa 310.573.0632 [email protected] ReFrame and IMDbPro Announce New Collaboration to Recognize Standout Gender-balanced Film and TV Projects The ReFrame Stamp is being Awarded to 12 Films from 2017 including Everything, Everything; Girls Trip; Lady Bird; The Post; and Wonder Woman Los Angeles, CA — ReFrame™, a coalition of industry professionals and partner companies founded by Women In Film and Sundance Institute whose mission is to increase the number of women of all backgrounds working in film, TV and media, and IMDbPro (http://www.imdbpro.com/), the leading information resource for the entertainment industry, today announced a new collaboration that leverages the authoritative data and professional resources of IMDbPro to recognize standout, gender- balanced film and TV projects. ReFrame is using IMDbPro data to determine recipients of a new ReFrame Stamp, and IMDbPro is providing digital promotion of ReFrame activities (imdb.com/reframe). Also announced today was the first class of ReFrame Stamp feature film recipients based on an extensive analysis of IMDbPro data on the top 100 domestic-grossing films of 2017. The recipients include Warner Bros.’ Everything, Everything, Universal’s Girls Trip, A24’s Lady Bird, Twentieth Century Fox’s The Post and Warner Bros.’ Wonder Woman. The ReFrame Stamp serves as a mark of distinction for projects that have demonstrated success in gender-balanced film and TV productions based on criteria developed by ReFrame in consultation with ReFrame Ambassadors (complete list below), producers and other industry experts. -

Oral History Interview – 5/25/1982 Administrative Information

Jack Valenti Oral History Interview – 5/25/1982 Administrative Information Creator: Jack Valenti Interviewer: Sheldon M. Stern Date of Interview: May 25, 1982 Length: 15 pp. Biographical Note Valenti was the Special Assistant to President Lyndon Johnson (1963-1966), Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of the Motion Picture Association of America (1966-2004). This interview focuses on Lyndon Johnson’s relationships with John and Robert F. Kennedy, his role as vice president, President Kennedy’s trip to Texas, and the plane ride following the assassination, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials have passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Paramount Pictures' 3-D Movie Transformers: Dark of The

PARAMOUNT PICTURES’3 -D MOVIE TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON LAUNCHES BACK INTO IMAX® THEATRES FOR EXTENDED TWO-WEEK RUN Film Grosses $1,095 Billion to Date Los Angeles, CA (August 23, 2011) – IMAX Corporation (NYSE:IMAX; TSX:IMX) and Paramount Pictures announced today that Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the third film in the blockbuster Transformers franchise, is returning to 246 IMAX® domestic locations for an extended two-week run from Friday, Aug. 26 through Thursday, Sept. 8. During those two weeks, the 3-D film will play simultaneously with other films in the IMAX network. Since its launch on June 29, Transformers: Dark of the Moon has grossed $1,095 billion globally, with $59.6 million generated from IMAX theatres globally. “The fans have spoken and we are excited to bring Transformers: Dark of the Moon back to IMAX theatres,”said Greg Foster, IMAX Chairman and President of Filmed Entertainment. “The film has been a remarkable success and we are thrilled to offer fans in North America another chance to experience the latest chapter in this history making franchise.”Transformers: Dark of the Moon: An IMAX 3D Experience has been digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology for presentation in IMAX 3D. The crystal-clear images, coupled with IMAX’s customized theatre geometry and powerful digital audio, create a unique immersive environment that will make audiences feel as if they are in the movie. About Transformers: Dark of the Moon Shia LaBeouf returns as Sam Witwicky in Transformers: Dark of the Moon. -

Oliver Stone Et Woody Allen Sèment Le Bonheur Sur La Croisette

Culture / Culture FESTIVAL DE CANNES Oliver Stone et Woody Allen sèment le bonheur sur la Croisette Les deux cinéastes américains, Oliver Stone et Woody Allen, qui ont présenté leur dernier film, respectivement, Wall Street : l'argent ne dort jamais, suite du filmWall Street, sorti en 1988, et You will meet a tall dark stranger, les deux présentés en Hors Compétition, ont ravi la vedette aux cinéastes en lice pour la plus haute distinction du festival : la Palme d'or. Commençons par Oliver Stone. Fidèle à lui-même, et toujours à l'avant-garde, il a exploré et dénoncé la dictature impitoyable de l'argent, imposée par les spéculateurs et grands banquiers de Wall Street. “Aléa moral, subprimes, intérêt, taux, bulle…” sont autant de mots barbares qui reviennent sans cesse dans le film. Pour rendre accessible ce monde complexe, il a imaginé une trame narrative simple et captivante. Il a mis en scène un jeune trader qui tente d'alerter le monde au sujet des dangers irréversibles de la spéculation financière. Dans le même temps, il cherche à venger la mort de son mentor, ruiné et poussé au suicide. L'une des remarques importantes que l'on puisse souligner est l'omniprésence des écrans, télévision et ordinateurs compris, quasiment propulsés au rang de personnages. Une présence qui permet la dénonciation de la sainte alliance entre le monde de la communication et celui de la finance qui rend le monde réduit à des bulles éphémères, davantage fragile et instable. Certains ont reproché au film sa fin quelque peu heureuse à la manière d'un conte. -

88Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Natalie Kojen [email protected] January 14, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 88TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, Guillermo del Toro, John Krasinski and Ang Lee announced the 88th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 14). Del Toro and Lee announced the nominees in 11 categories at 5:30 a.m. PT, followed by Boone Isaacs and Krasinski for the remaining 13 categories at 5:38 a.m. PT, at the live news conference attended by more than 400 international media representatives. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars® website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Official screenings of all motion pictures with one or more nominations will begin for members on Saturday, January 23, at the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theater. Screenings also will be held at the Academy’s Linwood Dunn Theater in Hollywood and in London, New York and the San Francisco Bay Area. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 88th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 28, 2016, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live by the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m.