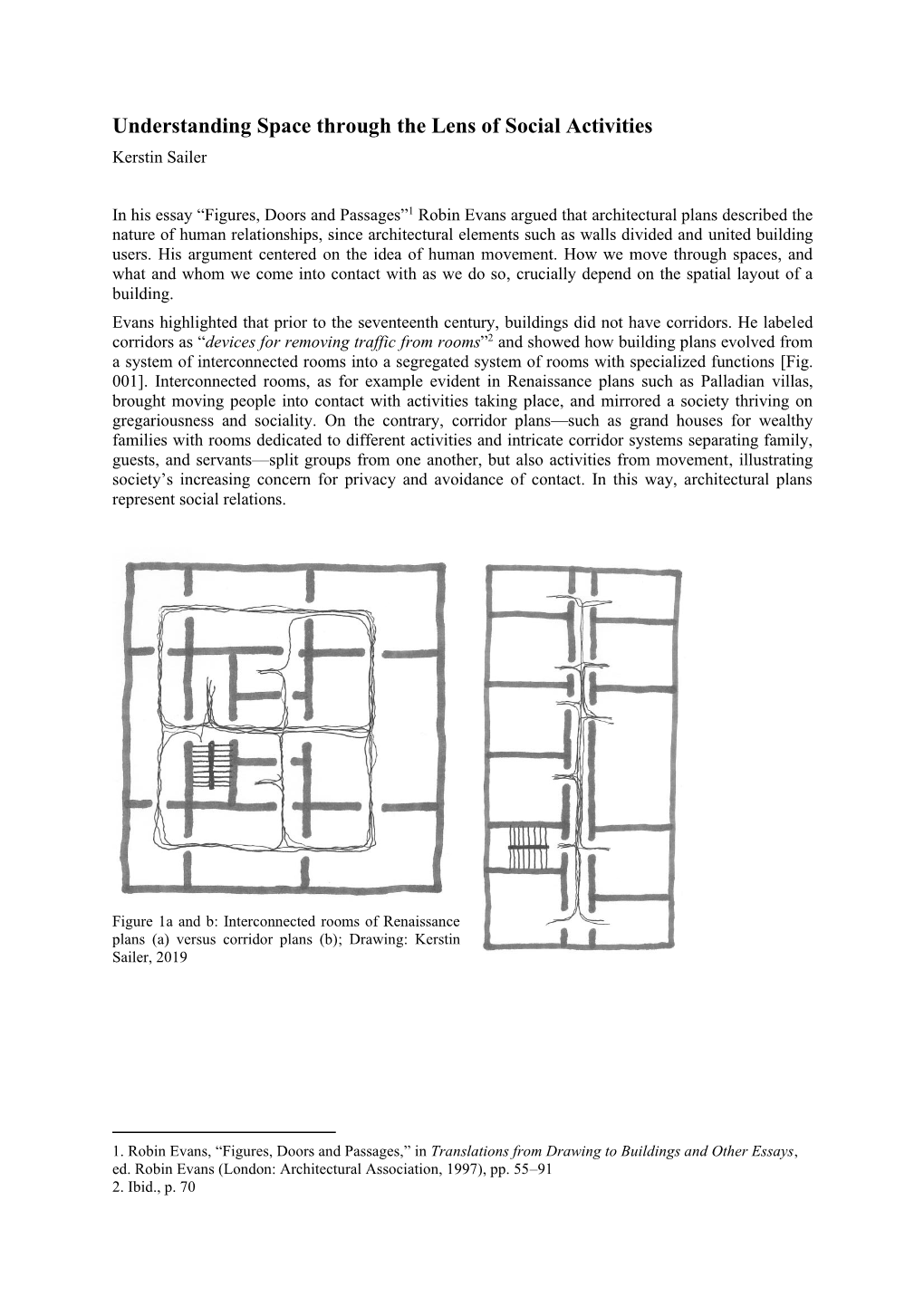

Understanding Space Through the Lens of Social Activities Kerstin Sailer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Library

PUBLIC SPACE AND THE ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT London Modernist Case Study Briefing (c. 2016 FABE Research Team, University of Westminster) THE BRITISH LIBRARY CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………... .......... 3 1. BUILDING CHRONOLOGY……………………………......... 4 2. POLICY AND IDEOLOGY………………………………........ 7 3. AGENTS……………………………………………………….. 12 4. BRIEF…………………………………………………….......... 14 5. DESIGN…………………………………………………………16 6. MATERIALS/CONSTRUCTION/ENVIRONMENT 22 7. RECEPTION…………………………………………….......... 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………….……… 26 PROJECT INFORMATION Case Study: The British Library, 96 Euston Rd, London NW1 2DB Dates: 1962 - 1998 (final plan 1977, build 1982-1999, staggered opening November 1997- June 1999) Architects: Colin St John Wilson with M.J. Long, John Collier, John Honer, Douglas Lanham, Peter Carolin Client: The British Museum, then The British Library (following Act of Parliament 1972) Contractors: Phase 1A, Laing Management Contracting Ltd. Completion phase, McAlpine/Haden Joint Venture Financing: National government Site area: 112,643 m2 (building footprint is 3.1 hectares, on a site of 5 hectares) Tender price: £511 million. Budget overrun: £350 million 2 SUMMARY The British Library, the United Kingdom’s national library and one of six statutory legal depositories for published material, was designed and constructed over a 30-year period. It was designed by Colin St John Wilson (1922 – 2007) with his partner M J Long (1939 – ), and opened to the public in 1997. As well as a functioning research library, conference centre and exhibition space, the British Library is a national monument, listed Grade I in 2015. Brian Lang, Chief Executive of the British Library during the 1990s, described it as “the memory of the nation’, there to ‘serve education and learning, research, economic development and cultural enrichment.’1 The nucleus of what is now known as the British Library was, until 1972, known as the British Museum Library. -

St Cross Building, 612/24/10029 University of Oxford

St. Cross Building Conservation Plan May 2012 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 1 Building No. 228 Oxford University Estates Services First draft March 2011 This draft May 2012 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 2 THE ST. CROSS BUILDING, OXFORD CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Purpose of the Conservation Plan 7 1.2 Scope of the Conservation Plan 8 1.3 Existing Information 9 1.4 Methodology 9 1.5 Constraints 9 2 UNDERSTANDING THE SITE 13 2.1 History of the Site and University 13 2.2 Design, Construction, and Subsequent History of the St. Cross 14 Building 3 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ST. CROSS BUILDING 21 3.1 Significance as part of the Holywell suburb, and the Central (City 21 and University) Conservation Area 3.2 Architectural Significance 24 3.3 Archaeological Significance 26 3.4 Significance as a major library and work space 27 3.5 Historical Significance 27 4 VULNERABILITIES 31 4.1 Access 31 4.2 Legibility 32 4.3 Maintenance 34 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 3 4.4 Health and Safety 40 5 CONSERVATION POLICY 43 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY 51 7 APPENDICES 55 Appendix 1: Listed Building Description 55 Appendix 2: Conservation Area Description 57 Appendix 3: Chronology of the St. Cross Building 61 Appendix 4: Checklist of Significant Features 63 Appendix 5: Floor Plans 65 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 4 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 5 THIS PAGE HAS BEEN LEFT BLANK St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 6 1 INTRODUCTION The St. -

Pallant House Gallery

__ The Economic Contribution of Pallant House Gallery 16 June 2016 Contents 5. Economic Model ............................................................................... 20 5.1 Additionality Analysis .......................................................................... 21 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 3 5.2 Economic Multipliers ........................................................................... 23 1.1 Growing Organisation ........................................................................... 3 5.3 GVA and FTE Conversion .................................................................. 23 1.2 Dedicated Audience ............................................................................. 3 5.4 Economic Modelling Results ............................................................... 24 1.3 Overall Economic Impact ..................................................................... 3 5.4.1 Audience Analysis ............................................................................... 24 1.4 Expansion since 2008 .......................................................................... 4 5.4.2 Organisation Analysis ......................................................................... 25 2. Introduction ........................................................................................ 5 5.4.3 Overall Assessment ............................................................................ 25 2.1 Methodological Overview .................................................................... -

Curriculum Vitae for Professor Peter Blundell Jones

Curriculum vitae for Professor Peter Blundell Jones. Qualifications: RIBA parts 1&2. A.A.Diploma. M.A.Cantab. Career Summary Born near Exeter, Devon, 4/1/49. Architectural education: Architectural Association, London, 1966-72. October 1972/ July 73: Employed by Timothy Rendle, ARIBA, in London, as architectural assistant. September 1973/ June 1974: Wrote book on Hans Scharoun, published by Gordon Fraser. September 1974/ June 1975: Part-time tutor at Architectural Association. July 1975/ May 1977: In Devon as designer and contractor for Round House at Stoke Canon near Exeter, published in The Architectural Review and now included in Pevsner’s Buildings of England. 1977/ 78: free-lance lecturer and architectural journalist. October 1978/ September 1983: Full time post as Assistant Lecturer in architecture at Cambridge University. Duties included lecture series in architectural theory, studio teaching, and examining. 1983/ 87: visiting lecturer at Cambridge University and Polytechnic of North London, free- lance journalist and critic writing for Architects’ Journal and Architectural Review, research on German Modernism focusing on Hugo Häring. Member of CICA, the international critics organisation. September 1988/ July 1994: full time post as Principal Lecturer in History and Theory at South Bank Polytechnic, later South Bank University. Visiting lecturer in other schools. External examiner 1988-91 to Hull school of architecture, and subsequently to Queen’s University Belfast. Readership at South Bank University conferred December 1992. Since August 1994: Professor of Architecture at the School of Architecture, University of Sheffield, with responsibility for Humanities. Member of the executive group, organiser and contributor to lecture courses and several external lecture series, reorganiser of the Diploma School in the late 1990s and studio leader, tutor of dissertations at both undergraduate and Diploma levels: heavy commitment in recent years to the humanities PhD programme. -

From Islands of Knowledge to Districts of Innovation Katharina Borsi* And

Typologies of KnowledgeUniversities and the City: from Islands of Knowledge to Districts of Innovation Katharina Borsi* and Chris Schulte aDepartment of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK; bDepartment of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK Dr Katharina Borsi Department of Architecture and Built Environment University Park Nottingham NG7 2RD UK Telephone: 0115 95 13172 Email: [email protected] ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6745-3547 Typologies of KnowledgeUniversities and the City: from Islands of Knowledge to Districts of Innovation We are witnessing a new trend in the design of university buildings and other ‘knowledge typologies’, that is, buildings in which knowledge is produced or disseminated, such as university buildings, research laboratories or libraries. Increasingly, their design inverts the image of the closed ‘ivory tower’ through a layered intersection of inside and outside spaces, seeking to draw the life of the city and the life of the institution closely together. Using London’s ‘Knowledge Quarter’ centred in Bloomsbury, Euston and King’s Cross as a focus, this paper traces a trajectory of typological evolution of university buildings which includes Adams, Holden and Pearson’s ‘ivory tower’ project for a new headquarter of the University of London (1932), of which only Senate House was built; Leslie Martin’s and Trevor Dannatt’s radical restructuring of the Georgian urban structure through the Development Plan of the University of London (1959); Denys Lasdun’s evolution and typological reworking of this plan through the Institute of Education (1970–1976) and the library of SOAS (1970-1973); Colin St John’s Wilson’s British Library (1982 - 1999); and Stanton Williams’ Central St Martins (2008- 2011). -

The British Library at St Pancras Building the Future

The British Library at St Pancras Building the future Second Edition Introduction: an evolving building In 2015 we published Living Knowledge, our We want the Library – one of the great public This brochure shares our vision to reorient and eight-year strategy which has at its heart a vision of buildings of the 20th century and Grade I listed – to expand our magnificent building’s capabilities so the British Library becoming the most open, creative evolve into one of the world’s great knowledge hubs that we are better able to anticipate and meet the and innovative institution of its kind in the world for the 21st century. Our physical spaces are now needs of our users, our local community and the by the time of our 50th anniversary in 2023. Our reaching capacity and our exhibition galleries are wider national and international network of libraries. ambitions for our St Pancras site are central to able to display only a fraction of the treasures that Working in tandem with our other major facility at achieving that vision. we hold. The huge success of recent exhibitions Boston Spa in Yorkshire, we want St Pancras to drive on Magna Carta, 20th Century Maps, the the next stage of the British Library’s evolution as a Since we opened our doors on Monday 24 November Russian Revolution and Harry Potter highlights global player in the knowledge economy. 1997, the British Library at St Pancras has become a growing public appetite for engaging with our an icon of the information age. The architect of this collection – if we could only expose a greater It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform remarkable building, the late Sir Colin St John Wilson proportion of it, whether on-site or online. -

Peter Carolin, Born 1936

PETER CAROLIN, BORN 1936 The fifth generation of a Scots South American family, Peter Carolin’s naval National Service included the Suez debacle of 1956. As an architect, he worked for John Voelcker of Team 10 and with Colin St John Wilson on the British Library. He edited both the Architect’s Journal, Magazine of the Year, 1985, and arq, which was awarded the learned journal equivalent, 2002. He was Professor and Head of the Department of Architecture at Cambridge, 1989- 2000, and chaired the Cambridge Futures project. Peter Carolin Architect, editor, academic Born 1936 Autobiographical life story Available online at www.livesretold.co.uk Contents 1. Introduction 2. The Irish and the Scots 3. A Rio Childhood 4. Prep School in Surrey 5. Radley and Holidays 6. The Navy and Suez 1956 7. Corpus and Cambridge 8. John Voelcker 9. The Bartlett 10. Sandy Wilson's Cambridge Practice 11. London and the British Library 12. Cambridge Design 13. The AJ 14. Cambridge yet again 15. Retirement 16. Sailing 17. Birgit and our children 18. Looking back 1. Introduction My father, a pipe smoker, was an unliterary man. And yet he loved books. He had an extraordinarily fine collection of antiquarian editions on Brazil. But I never saw him reading any of them and the only writing of his own that survives are his meticulous account books and a dry-as-dust book on how to set up a company in Brazil. We never tried to persuade him to write a memoir of his life – I think we knew that he wouldn’t have done so, for his Irishness was of a rather puritan kind and, despite an interesting life, he was not a man to talk about it or to see it in a wider perspective. -

Tobacco Dock, 6 by Michael Courtney and Richard Matthews

THE ARUP JOURNAL AUTUMN 1988 Vol.23 No.3 Autumn 1988 Contents Published by Ove Arup Partnership THEARUP 13 Fitzroy Street, London Wl P 680 Editor· David Brown JOURNAL Art Editor: Desmond Wyeth FCSD Progress at the British Library, 2 by Peter Ryalls and Tony Stevens Tobacco Dock, 6 by Michael Courtney and Richard Matthews Flue gas desulphurization study, 12 by Malcolm Nayee, Paul Johnson and Charles Milloy Glasgow Garden Festival: 14 Maritime Area and Pavilions, by Alistair Smith Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, 17 by Robert Pugh Front cover: Vaults at Tobacco Dock (Photo: Richard Matthews) Back cover: The British Library under construction, August 1988 (Photo: Peter Mackinven) Tests to explore the feasibility of forming pile The heights and forms of the roofscape of the Progress at the underreams in the Woolwich and Reading Rare Books Reading Rooms were informed Beds were undertaken early in 19793. But by light angles to Levita House, a block of British Library the preliminary contract for secant pile walls, council dwellings. The architects have piling and some excavation did not begin planned the closed access Reading Rooms Architect: until April 1982. Substantive work on Phase to be interconnected level by level and Colin St. John Wilson & Partners 1AA began in July 1984. illuminated from above by clerestory and skylights. Planning objectives Peter Ryalls The departments of the British Museum The height and bulk of the buildings of the Library to be transferred to the British Library British Library, especially the Science Refer Tony Stevens at Euston comprise: ence Library, are governed by planning con ditions dictated in part by the presence of St. -

The British Library at St Pancras Building the Future Introduction: an Evolving Building

The British Library at St Pancras Building the future Introduction: an evolving building In January this year we published our new We want the Library – one of the great public This brochure introduces our vision to reorient strategy, Living Knowledge, which has at its buildings of the 20th century and now a and expand this magnificent building’s capabilities heart a vision of the British Library becoming Grade I listed building – to evolve into one so that we are better able to anticipate and meet the most open, creative and innovative institution of the world’s great knowledge hubs for the the needs of our users, our local community and of its kind in the world by the time of our 50th 21st century. Our physical spaces are now the wider national and international network anniversary in 2023. Our ambitions for our St reaching capacity and our exhibition galleries of libraries. Working in tandem with our other Pancras site are central to achieving that vision. are able to display only a fraction of the major facility at Boston Spa in Yorkshire, we treasures that we hold. The huge success of want St Pancras to drive the next stage of the Since we opened our doors to users on recent exhibitions on Comics, Propaganda, British Library’s evolution as a global player in Monday 24 November 1997, the British Library Gothic literature and Magna Carta highlights the knowledge economy. at St Pancras has become an icon of the a growing public appetite for engaging with our information age. collections – if we could only expose a greater It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to proportion of them, whether on-site and online. -

The Smithsons, Colin St John Wilson, and the Writing of Architectural History

The practice of history: the Smithsons, Colin St John Wilson, and the writing of architectural history M. J. Wells Introduction In 1967 John Summerson noted ‘There was a time, within living memory, when all, or nearly all, architectural history in England was written by architects; and not only architects but by the biggest and best architects…But somewhere about 1934 the game came to an end’.1 This reflection was based on the arrival of the Fritz Saxl and the Warburg Library in 1933, shortly followed by Rudolph Wittkower and Nikolaus Pevsner in 1934, and their collective effect on the study of history in Britain. This is well-trodden ground.2 Somewhat counter to Summerson, this essay proposes to analyse the architectural history written by practicing architects following the arrival of kunstgeschichte in Britain. The distinction between practicing architects and the ‘architecturally trained’ is an important one. First, the study of history written by architects is an underexplored domain. Various studies focus on the lack of history written by architects or the influence on them by historians rather than directly examine the scholarship produced. David Watkin’s The Rise of Architectural History proposed applying E.H. Carr’s famous advice – ‘Before you study the history, study the historian’ – to the analysis of architectural history on account of its origin from practising architects.3 However, Watkin failed to discuss any history written by architects in his discussion of twentieth-century architectural historiography.4 Second, the relationship between contemporary history and the actions of architectural practice has consequential effects on all forms of architectural culture including practice and historical leanings. -

Architects, Designers, Sculptors and Craftsmen from 1530

ARCHITECTS, DESIGNERS, SCULPTORS AND CRAFTSMEN FROM 1530 R-Z RAMSEY FAMILY (active c.14) Whittington, A. 1980 The Ramsey family of Norwich, Archaeological Journal 137, 285–9 REILLY, Sir Charles H. (1874–1948) Reilly, C.H. 1938 Scaffolding in the Sky: a semi-architectural autobiography Sharples, J., Powers, A., and Shippobottom, M. 1996 Charles Reilly & the Liverpool School of Architecture, 1904–33 RENNIE, John (1761–1821) Boucher, C.T.G. 1963 John Rennie, the life and work of a great engineer RENTON HOWARD WOOD LEVIN PARTNERSHIP Wilcock, R. 1988 Thespians at RHWL, R.I.B.A. Journal 95 (June), 33–9 REPTON, George (1786-1858) Temple, N. 1993 George Repton’s Pavilion Notebook: a catalogue raisonne REPTON, Humphry (1752–1818), see C2 REPTON, John Adey (1775–1860) Warner, T. 1990 Inherited Flair for Rural Harmony, Country Life. 184 (12 April), 92–5. RICHARDSON, Sir A.E. (1880–1964) Houfe, S. 1980 Sir Albert Richardson – the professor Powers, A. 1999 Sir Albert Richardson (RIBA Heinz Gallery exhibition catalogue) Taylor, N. 1975 Sir Albert Richardson: a classic case of Edwardianism, Edwardian Architecture and its Origins, ed. A. Service, 444–59 RICKARDS, Edwin Alfred (1872–1920) Rickards, E.A. 1920 Architects 1 The Art of E.A. Rickards (with a personal sketch by Arnold Bennett) Warren, J. 1975 Edwin Alfred Rickards, Edwardian Architecture and its Origins, ed. A. Service, 338–50 RICKMAN, Thomas (1776–1841) Aldrich, M. 1985 Gothic architecture illustrated: the drawings of Thomas Rickman in New York, Antiq. J. 65 Rickman, T.M. 1901 Notes of the Life of Thomas Rickman Sleman, W. -

Saint Lawrence Chapel, by Avanto Architects

A Convergence of Traditions: Saint Lawrence Chapel, by Avanto Architects Abstract: Debates on the actuality of modern architecture by new contributions could be considered by critics as a deviation from its essence. In such a context, some works by Finnish studies exhibited at the Museum of Finnish Architecture in Spring, 2015 provide fresh approaches with their proposals and interest us here to reconsider architectural modernity with alterative readings. Project ideas are fused and converge towards new proposals in a process of continuity, from which only the concrete buildings experience, with enlightening phenomenal qualities, redeem us. We concentrate on a chapel by Avanto Architects in which interests from the second generation of modern architecture and the masters of Nordic Architecture can be appreciated. Keywords: architectural competitions, modernity and representation, nordic architecture. The work of seven Finnish teams was exhibited in the National Museum of Finnish Architecture during the Spring of 2015, under the heading Suomi Seven: Emerging Architects from Finland, reconsidering continuities of Modern Movement, scale, new housing types, collective services buildings –schools or churches- amongst other issues.1 We choose the Chapel of Saint Lawrence by Avanto Architects for detailed consideration. Modernity and postmodern complexities. Whilst searching authenticity in Nordic Architecture, Nils-Ole Lund recalled the neglect of gestural subtleties after Gunnar Asplund’s death in 1940, favouring settings, clear constructions and final consistency: such in the case of Sigurd Lewerentz. 2 Modern Architectural matters seemed difficult to explain, since functionalist, organic, vernacular or Critical Regionalism values were recovered, together with the constructivist avant-garde or Merzbau/Dada themes.3 Since tradition and individual talent do not combine well, some authors suggested a revision of the previous order, differentiating evaluations of sincere expression, technical excellence or the exhibition of significant emotion.