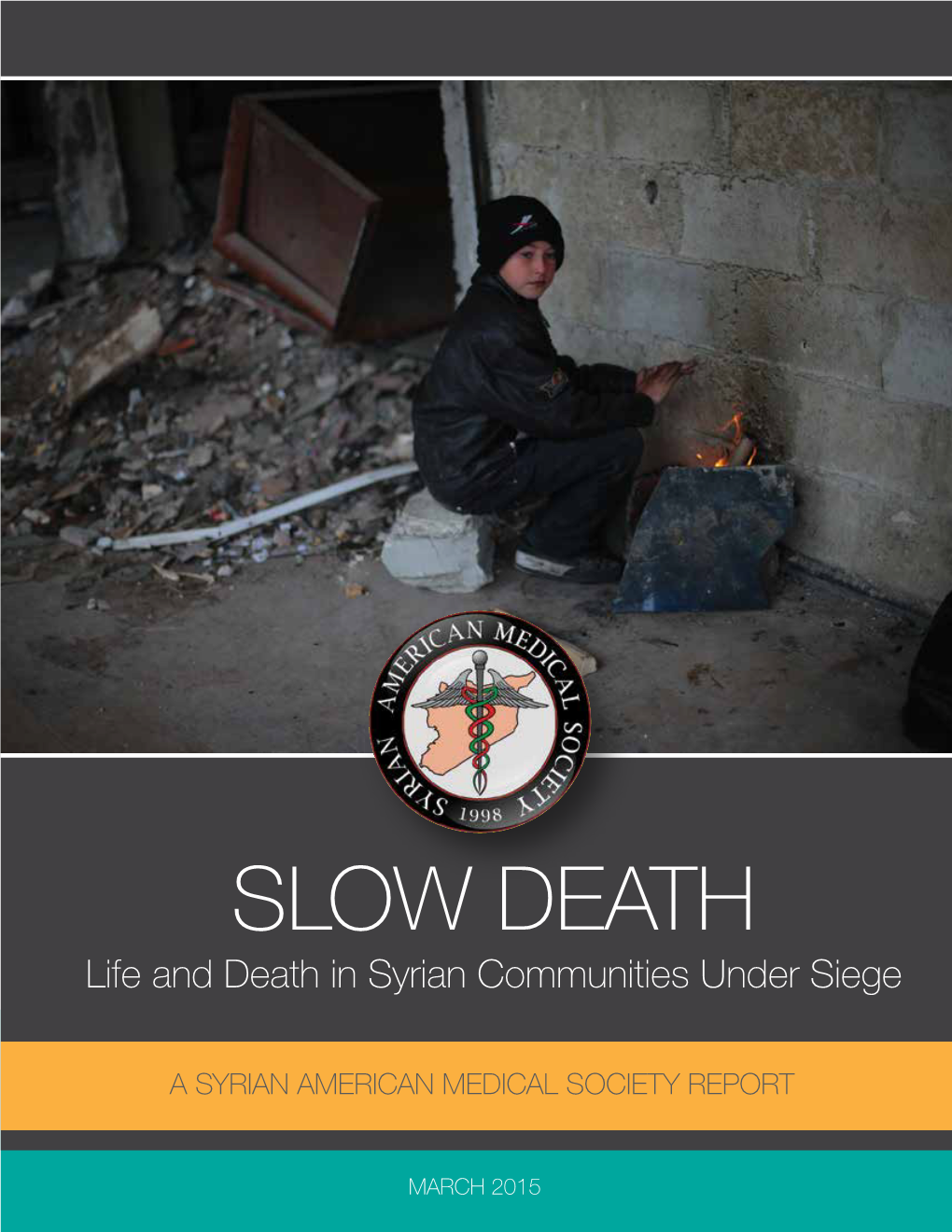

Life and Death in Syrian Communities Under Siege

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – March 2018 Page 1

Aid in Danger Aid agencies Monthly News Brief March 2018 Insecurity affecting the delivery of aid Security Incidents and Access Constraints This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of Africa violence affecting the delivery Central African Republic of aid. It is prepared by 05 March 2018: In Paoua town, Ouham-Pendé prefecture, and across Insecurity Insight from the wider Central African Republic, fighting among armed groups information available in open continues to stall humanitarian response efforts. Source: Devex sources. 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, rumours of All decisions made, on the basis an armed attack in the city forced several unspecified NGOs to of, or with consideration to, withdraw. Source: RJDH such information remains the responsibility of their 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, protesters at respective organisations. a women’s march against violence in the region called for the departure of MINUSCA and the Moroccan UN contingent from Editorial team: Bangassou, accusing them of passivity in the face of threats and Christina Wille, Larissa Fast and harassment. Source: RJDH Laurence Gerhardt Insecurity Insight 09 or 11 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, armed men suspected to be from the Anti-balaka movement invaded the Andrew Eckert base of the Dutch NGO Cordaid, looting pharmaceuticals, work tools, European Interagency Security motorcycles and seats. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Forum (EISF) Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) personnel intervened, leading to a firefight between MINUSCA and the armed Research team: men. The perpetrators subsequently vandalised the local Médecins James Naudi Sans Frontières (MSF) office. Cars, motorbikes and solar panels Insecurity Insight belonging to several NGOs in the area were also stolen. -

Forgotten Lives Life Under Regime Rule in Former Opposition-Held East Ghouta

FORGOTTEN LIVES LIFE UNDER REGIME RULE IN FORMER OPPOSITION-HELD EAST GHOUTA A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE AND ETANA SYRIA MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-10 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * KEY POINTS AND STATISTICS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 2 MAIN AREAS OF CONTROL * 3 MAP OF EAST GHOUTA * 6 MOVEMENT OF CIVILIANS * 8 DETENTION CENTERS * 9 PROPERTY AND REAL ESTATE UPHEAVAL * 11 CONCLUSION Cover Photo: Syrian boy cycles down a destroyed street in Douma on the outskirts of Damascus on April 16, 2018. (LOUAI BESHARA/AFP/Getty Images) © The Middle East Institute Photo 2: Pro-government soldiers stand outside the Wafideen checkpoint on the outskirts of Damascus on April 3, 2018. (Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/ The Middle East Institute AFP) 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY A “black hole” of information due to widespread fear among residents, East Ghouta is a dark example of the reimposition of the Assad regime’s authoritarian rule over a community once controlled by the opposition. A vast network of checkpoints manned by intelligence forces carry out regular arrests and forced conscriptions for military service. Russian-established “shelters” house thousands and act as detention camps, where the intelligence services can easily question and investigate people, holding them for periods of 15 days to months while performing interrogations using torture. The presence of Iranian-backed militias around East Ghouta, to the east of Damascus, underscores the extent of Iran’s entrenched strategic control over key military points around the capital. As collective punishment for years of opposition control, East Ghouta is subjected to the harshest conditions of any of the territories that were retaken by the regime in 2018, yet it now attracts little attention from the international community. -

"Al-Assad" and "Al Qaeda" (Day of CBS Interview)

This Document is Approved for Public Release A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad A Quick Look Assessment by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA)1 Part II: Analytical Approaches2 February 2014 Contributors: Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (University of British Columbia), Mr. Ryan W. Cross (University of British Columbia) Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Maj Jason Spitaletta (Joint Staff J-7 & Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Kathleen Egan (CTTSO), Mr. Sean Colbath (BBN), Mr. Paul Brewer (SDL), Ms. Martha Lillie (BBN), Mr. Dana Rafter (CSIS), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M), Ms. Jacquelyn Chinn (Texas A&M), Mr. Patrick Issa (Texas A&M) Edited by: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J-38) and Dr. Nicholas Wright, MRCP PhD (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Copy Editor: Mr. Sam Rhem (SRC) 1 SMA provides planning support to Combatant Commands (CCMD) with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff, J3, DDSAO and executed by OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO. 2 This is a document submitted to provide timely support to ongoing concerns as of February 2014. 1 This Document is Approved for Public Release 1 ABSTRACT This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources. -

September 2016

www.rbs0.com/syria37.pdf 1 Oct 2016 Page 1 of 234 Syria & Iraq: September 2016 Copyright 2016 by Ronald B. Standler No copyright claimed for quotations. No copyright claimed for works of the U.S. Government. Table of Contents 1. Chemical Weapons U.N. Security Council begins to ask who used chemical weapons in Syria? ISIL used mustard in Iraq (11 Aug 2015) 2. Syria United Nations Diverted from Syria death toll in Syria now over 301,000 (30 Sep) Free Syrian Army is Leaderless since June 2015 Turkey is an ally from Hell U.S. troops in Syria Recognition that Assad is Winning the Civil War Peace Negotiations for Syria Future of Assad must be decided by Syrians Planning for Peace Negotiations in Geneva New Russia/USA Agreements (9 Sep) U.N. Security Council meeting (21 Sep) Syrian speech to U.N. General Assembly (24 Sep) more meetings and negotiations 22-30 Sep 2016 Friends of Syria meeting in London (7 Sep) ISSG meetings (20, 22 Sep 2016) occasional reports of violations of the Cessation of Hostilities agreement proposed 48-hour ceasefires in Aleppo siege of Aleppo (1-12 Sep} Violations of new agreements in Syria (12-19 Sep) continuing civil war in Syria (20-30 Sep) bombing hospitals in Syria surrender of Moadamiyeh U.N. Reports war crimes prosecution? 3. Iraq Atrocities in Iraq No Criminal Prosecution of Iraqi Army Officers No Prosecution for Fall of Mosul No Prosecution for Rout at Ramadi No Criminal Prosecution for Employing "Ghost Soldiers" www.rbs0.com/syria37.pdf 1 Oct 2016 Page 2 of 234 Iraq is a failed nation U.S. -

Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria

A NEW NORMAL Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria February 2016 SYRIAN AMERICAN MEDICAL SOCIETY C1 Above: Bab Al Hawa Hospital, Idlib, April 21, 2014. On the cover, top: Bab Al Hawa Hospital, Idlib, April 21, 2014; bottom: Binnish, Idlib, March 23, 2015. ABOUT THE SYRIAN AMERICAN MEDICAL SOCIETY The Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) is a non-profit, non-political, professional and medical relief orga- nization that provides humanitarian assistance to Syrians in need and represents thousands of Syrian American medical professionals in the United States. Founded in 1998 as a professional society, SAMS has evolved to meet the growing needs and challenges of the medical crisis in Syria. Today, SAMS works on the front lines of crisis relief in Syria and neighboring countries to serve the medical needs of millions of Syrians, support doctors and medical professionals, and rebuild healthcare. From establishing field hospitals and training Syrian physicians to advocating at the highest levels of government, SAMS is working to alleviate suffering and save lives. Design: Sensical Design & Communication C2 A NEW NORMAL: Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria Acknowledgements New Normal: Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria was written by Kathleen Fallon, Advocacy Manager of the Syrian Amer- A ican Medical Society (SAMS); Natasha Kieval, Advocacy Associate of SAMS; Dr. Zaher Sahloul, Senior Advisor and Past President of SAMS; and Dr. Houssam Alnahhas of the Union of Medical Care and Relief Or- ganizations (UOSSM), in partnership with many SAMS colleagues and partners who provided insight and feedback. Thanks to Laura Merriman, Advocacy Intern of SAMS, for her research and contribution to the report’s production. -

Tenth Quarterly Report Part 1 – Eastern Ghouta February

Tenth Quarterly Report Part 1 – Eastern Ghouta February – April 2018 Colophon ISBN: 978-94-92487-29-2 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2018/05 Photo cover: “A raid killed my dream, and a raid killed my future, and a raid killed everything alive inside of me, while I was watching.” - Wael al-Tawil, Douma, 20 February 2018 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] This report was written by Valerie Szybala with support from the PAX team. It would not have been possible without the participation of Siege Watch’s voluntary network of reporting contacts on the ground. This past quarter, Siege Watch contacts from Eastern Ghouta continued to provide updates and information with the project during the darkest period of their lives. Thank you to everyone from Eastern Ghouta who communicated with the project team over the years, for your openness, generosity and patience. We have been inspired and humbled by your strength through adversity, and will continue to support your search for justice and peace. Siege Watch Tenth Quarterly Report Part 1 – Eastern Ghouta February – April 2018 PAX ! Siege Watch - Tenth Quarterly Report Part 1 – Eastern Ghouta 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary 06 Introduction 10 Eastern Ghouta 12 Background 12 Military Developments 14 Stages of the Final Offensive 18 Chemical Weapons -

Fractured Walls... New Horizons: Human Rights in the Arab Region

A-PDF MERGER DEMO Fractured Walls... New Horizons Human Rights in the Arab Region Annual Report 2011 (1) Fractured Walls... New Horizons Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies Human Rights in the Arab Region CIHRS Annual Report 2011 Reform Issues (29) Publisher: Cairo Institute for Human Cofounder Rights Studies (CIHRS) Dr. Mohammed El-Sayed Said Address: 21 Abd El-Megid El-Remaly St, 7th Floor, Flat no. 71, Bab El Louk, Cairo. POBox: 117 Maglis ElShaab, Cairo, Egypt President Kamal Jendoubi E-mail address: [email protected] Website: www.cihrs.org Tel: (+202) 27951112- 27963757 Director Bahey eldin Hassan Fax: (+202) 27921913 Cover designer: Kirolos Nathan Layout: Hesham El-Sayed Dep. No: 2012/ 10278 Index card Fractured Walls... New Horizons Human Rights in the Arab Region Annual Report 2010 Publisher: Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) Reform Issues (29), 24cm, 278 Pages, (Cairo) Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (Author) With support from The European Commission The Open Society Foundation (2) Table of Contents Dedication 5 Introduction: The Arab Spring: A Struggle on Three Fronts 7 Part One: Limits of the “Arab Spring” 23 Report Summary: Human Rights in the Context of the “Arab Spring” 25 The “Arab Spring” at the United Nations: Between Hope and Despair 45 Part Two: Human Rights in the Arab World 81 Section One – The Problem of Human Rights and Democracy 81 1- Egypt 83 2- Tunisia 103 3- Algeria 119 4- Morocco 129 5- Syria 143 6- Saudi Arabia 159 7- Bahrain 173 Section Two – Countries under Occupation and Armed Conflict -

Shifting Gears: Hts’S Evolving Use of Svbieds During the Idlib Offensive of 2019-20

SHIFTING GEARS: HTS’S EVOLVING USE OF SVBIEDS DURING THE IDLIB OFFENSIVE OF 2019-20 HUGO KAAMAN OCTOBER 2020 POLICY PAPER CONTENTS SUMMARY Since May 2019, a series of Syrian loyalist offensives backed by the Russian * 1 BACKGROUND air force has gradually encroached upon the country’s northwestern Idlib Province, home to the last major pocket of opposition-held territory. As the chief rebel group in control of Idlib, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has * 5 THE 2019 OFFENSIVE employed dozens of suicide car bombs as part of its continued defense of the area. Formally known as suicide vehicle-born improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs), these weapons have been a cornerstone of the group’s * 13 DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF TACTICS, TECHNIQUES, — and by extension, the entire opposition’s — military strategy since early stages of the war, when rebel forces began capturing and holding territory. AND PROCEDURES In an attempt to further understand this strategy and how it has evolved over time, this case study seeks to compare and contrast HTS’s past and current use of SVBIEDs, with a heavy focus on the latter. It will also examine * 19 CONCLUSION HTS’s evolving SVBIED design, paying particular attention to technical innovations such as environment-specific paint schemes, drone support teams, tablets with target coordinates, and live camera feeds, as well as * 20 ENDNOTES upgraded main charges. MAP OF HTS SVBIED ATTACKS, 2019-20 Cover photo: An up-armored SVBIED based on a pick-up truck used by HTS against a Syrian loyalist position near Abu Dali/Mushayrifa in eastern Hama on Oct. -

“We've Never Seen Such Horror”

Syria HUMAN “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” RIGHTS Crimes against Humanity by Syrian Security Forces WATCH “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” Crimes against Humanity by Syrian Security Forces Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-778-7 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org June 2011 1-56432-778-7 “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” Crimes against Humanity by Syrian Security Forces Summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 Note on Methodology .................................................................................................................. 7 I. Timeline of Protest and Repression in Syria ............................................................................ 8 II. Crimes against Humanity and Other Violations in Daraa ...................................................... -

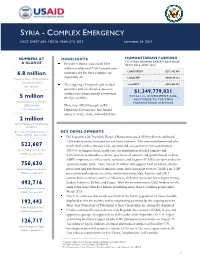

Syria Complex Emergency Fact Sheet

SYRIA - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #24, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2013 SEPTEMBER 24, 2013 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE TO SYRIA HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE President Obama announced $339 IN FY 2012 AND 2013 million in additional USG humanitarian 1 assistance for the Syria response on USAID/OFDA $271,995,689 6.8 million September 24. 2 People in Need of Humanitarian USAID/FFP $442,699,121 Assistance in Syria The targeting of hospitals and medical State/PRM3 $635,084,221 U.N. – April 2013 personnel and the denial of access to medical care is increasingly common in $1,349,779,031 TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT (USG) 5 million the Syria conflict. ASSISTANCE TO THE SYRIA Internally Displaced Persons HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE (IDPs) in Syria More than 500,000 people in Rif U.N. – September 2013 Damascus Governorate face limited access to water, food, and medical care. 2 million Syrian Refugees in Neighboring Countries Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for KEY DEVELOPMENTS Refugees (UNHCR) – September 2013 On September 24, President Barack Obama announced $339 million in additional USG humanitarian assistance for the Syria response. The new contribution includes 523,607 nearly $161 million through U.N. agencies and non-governmental organizations Syrian Refugees in Jordan (NGOs) to support food, health care, the distribution of relief supplies and UNHCR – September 2013 winterization commodities, shelter, psychosocial support, and gender-based violence (GBV) response, as well as water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) activities and other 756,630 assistance inside Syria. More than $179 million will support food assistance, shelter, Syrian Refugees in Lebanon protection and psychosocial support, camp and registration services, health care, GBV UNHCR – September 2013 prevention and response activities, winterization materials, logistics and relief commodities, nutrition, access to education, and other assistance for refugees in Iraq, 492,716 Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Egypt. -

Syria: Security and Socio-Economic Situation in Damascus and Rif

COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2020 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) SYRIA Security and socio-economic situation in the governorates of Damascus and Rural Damascus This brief report is not, and does not purport to be, a detailed or comprehensive survey of all aspects or the issues addressed in the brief report. It should thus be weighed against other country of origin information available on the topic. The brief report at hand does not include any policy recommendations or analysis. The information in the brief report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Danish Immigration Service. Furthermore, this brief report is not conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. October 2020 All rights reserved to the Danish Immigration Service. The publication can be downloaded for free at newtodenmark.dk The Danish Immigration Service’s publications can be quoted with clear source reference. © 2020 The Danish Immigration Service The Danish Immigration Service Farimagsvej 51A 4700 Næstved Denmark SYRIA – SECURITY AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC SITUATION IN THE GOVERNORATES OF DAMASCUS AND RURAL DAMASCUS Executive summary Since May 2018, the Syrian authorities have had full control over the governorates of Damascus and Rural Damascus. The security grip in former-opposition controlled areas in Damascus and Rural Damascus is firm, and these areas are more secure than other areas in the south such as Daraa. However, the number of targeted killings and assassinations of military and security service officers and affiliated officials increased during 2020. -

Access Denied UN Aid Deliveries to Syria’S Besieged and Hard-To-Reach Areas

Physicians for Human Rights Access Denied UN Aid Deliveries to Syria’s Besieged and Hard-to-Reach Areas March 2017 Death by infection because security forces do not allow antibiotics through checkpoints. Death in childbirth because relentless bombing blocks access to clinics. Death from diabetes and kidney disease because medicines to treat chronic illnesses ran out months ago. Death from trauma because snipers stand between injured children and functioning hospitals. And – everywhere – slow, painful death by starvation. This is what one million besieged people – trapped mostly by their own government – face every day in Syria. This is the unseen suffering – hidden under the shadow of barrel bombs and car bombs – that plagues the Syrian people as they enter a seventh grim year of conflict. This is murder by siege. Cover: Syrians unloading an aid Contents Acknowledgements convoy in the opposition-held 3 Introduction This report was written by Elise Baker, town of Harasta in May 2016, the 4 Methodology and Limitations research coordinator at Physicians for first UN interagency convoy to 5 Besiegement and Aid: 2011-2015 Human Rights (PHR). The report benefitted reach people trapped there since 6 2016 Aid Deliveries: Access from review by PHR staff, including the start of a government siege in Denied, Blocked, or Limited DeDe Dunevant, director of communications, 2013. However, the delivery only by Syrian Authorities Carolyn Greco, senior U.S. policy associate, provided aid for 10,000 people – 14 Conclusion Donna McKay, executive director, about half the area’s population – 15 Recommendations Marianne Møllmann, director of research and and crucial medical supplies, 16 Endnotes investigations, and Susannah Sirkin, director including surgical and burn kits, of international policy and partnerships.