Final Report out of Sight, out of Mind: the Aftermath of Syria's Sieges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

FSS Wos Response Analysis

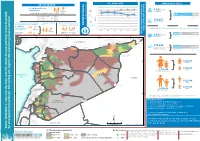

SO1 RESPONSE MARCH 2017 CYCLE Y PEOPLE IN NEED N I 8 B G Food & Livelihood 7.0 7.0 7.0 I 9 7 6.3 6.3 6.3 5.38million Assistance HED OR Food Basket Million C e 6 l Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 6.16 D SO1 5.8 5.89 5.78 5 N 4 M m 1.16.338m M 5.38 3.35 Target REA September 2015 8.7 Million 5.15 A From within Syria From neighbouring e 4 countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA ES ES Million peop I nc September 2016 9.0 Million 129,657 3 Cash and Voucher ITI LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING AR ta OVERALL TARGET MARCH 2017 RESPONSE 2 BENEFICIARIES Reached s FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher i Beneficiaries 1 Food Basket, ICI Cash & Voucher - ODAL Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided ss 7 EF 5.38 0 life sustaining Million M 9 Million OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB MAR N a E nsecure Million Emergency i d B 2 Response (77%) of SO1 Target o 608,654 1.84 M Million Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.45million From within Syria From neighbouring od 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E Bread-Flour fo countries 7 7 o c 1 Cizre- f 1 0 g! i 0 ng 2 Nusaybin-Al i 2 Kiziltepe-Ad l T U R K E Y Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y Darbasiyah n Ayn al g! ! g! h g Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras c b Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya 170,555 r Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa tai Akcakale-Tall ! Emergency Response with 116,265 a g! g! g g! 54,290 u Bab As Abiad Ready to Eat Ration From neighbouring M Salama Cobanbey g! From within Syria - countries ssessed g! g! p sus ) a 1 t e Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H fe -

Access Resource

The State of Justice Syria 2020 The State of Justice Syria 2020 Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) March 2020 About the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre The Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) strives to prevent impunity, promote redress, and facilitate principled reform. SJAC works to ensure that human rights violations in Syria are comprehensively documented and preserved for use in transitional justice and peace-building. SJAC collects documentation of violations from all available sources, stores it in a secure database, catalogues it according to human rights standards, and analyzes it using legal expertise and big data methodologies. SJAC also supports documenters inside Syria, providing them with resources and technical guidance, and coordinates with other actors working toward similar aims: a Syria defined by justice, respect for human rights, and rule of law. Learn more at SyriaAccountability.org The State of Justice in Syria, 2020 March 2020, Washington, D.C. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teach- ing or other non-commercial purposes, with appropriate attribution. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for commercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Cover Photo — A family flees from ongoing violence in Idlib, Northwest Syria. (C) Lens Young Dimashqi TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Introduction 4 Major Violations 7 Targeting of Hospitals and Schools 8 Detainees and Missing Persons 8 Violations in Reconciled Areas 9 Property Rights -

Axis Blitzkrieg: Warsaw and Battle of Britain

Axis Blitzkrieg: Warsaw and Battle of Britain By Skyla Gabriel and Hannah Seidl Background on Axis Blitzkrieg ● A military strategy specifically designed to create disorganization in enemy forces by logical firepower and mobility of forces ● Limits civilian casualty and waste of fire power ● Developed in Germany 1918-1939 as a result of WW1 ● Used in Warsaw, Poland in 1939, then with eventually used in Belgium, the Netherlands, North Africa, and even against the Soviet Union Hitler’s Plan and “The Night Before” ● Due to the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, once the Polish state was divided up, Hitler would colonize the territory and only allow the “superior race” to live there and would enslave the natives. ● On August 31, 1939 Hitler ordered Nazi S.S. troops,wearing Polish officer uniforms, to sneak into Poland. ● The troops did minor damage to buildings and equipment. ● Left dead concentration camp prisoners in Polish uniforms ● This was meant to mar the start of the Polish Invasion when the bodies were found in the morning by Polish officers Initial stages ● Initially, one of Hitler’s first acts after coming to power was to sign a nonaggression pact (January 1934) with Poland in order to avoid a French- Polish alliance before Germany could rearm. ● Through 1935- March 1939 Germany slowly gained more power through rearmament (agreed to by both France and Britain), Germany then gained back the Rhineland through militarization, annexation of Austria, and finally at the Munich Conference they were given the Sudetenland. ● Once Czechoslovakia was dismembered Britain and France responded by essentially backing Poland and Hitler responded by signing a non-aggression with the Soviet Union in the summer of 1939 ● The German-Soviet pact agreed Poland be split between the two powers, the new pact allowed Germany to attack Poland without fear of Soviet intervention The Attack ● On September 1st, 1939 Germany invaded Warsaw, Poland ● Schleswig-Holstein, a German Battleship at 4:45am began to fire on the Polish garrison in Westerplatte Fort, Danzig. -

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012

United Nations S/2012/550 Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, and 2, 3, 9 and 11 July 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 9 July 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-58099 (E) 271112 281112 *1258099* S/2012/550 Annex to the identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Monday, 9 July 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2200 hours on it July 2012, an armed terrorist group abducted Chief Warrant Officer Rajab Ballul in Sahnaya and seized a Government vehicle, licence plate No. 734818. 2. At 0330 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on the law enforcement checkpoint of Shaykh Ali, wounding two officers. 3. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device as a law enforcement overnight bus was passing the Artuz Judaydat al-Fadl turn-off on the Damascus-Qunaytirah road, wounding three officers. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

Why Tackling Energy Governance in Developing Countries Needs a Different Approach

Why Tackling Energy Governance in Developing Countries Needs a Different Approach June 2021 | Neil McCulloch CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 The Nature of the Challenge ...................................................................................................... 1 The Current Approach ................................................................................................................ 3 How Energy Governance Affects Performance ......................................................................... 6 The Political Economy of Power ................................................................................................ 9 A New Approach to Energy Governance ................................................................................. 14 Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 19 References ............................................................................................................................... 22 Annex A. Thinking and Working Politically in USAID Energy Projects .................................... 25 A. Introduction Global efforts to improve energy access and quality and to tackle climate change need a different approach to addressing poor energy governance. In 2015, leaders from around the world agreed to 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030.1 The -

HOW to HELP SYRIA RECOVER? Policy Paper 2

HOW TO HELP SYRIA RECOVER? Policy Paper 2 Author: Collective of the “SDGs and Migration“ project This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of Diaconia of the ECCB and can under no cirmustances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. The document is part of the „SDGs and Migration – Multipliers and Journalists Addressing Decision Makers and Citizens“ project which is realized in the framework of the Development Education and Awareness Raising (DEAR) programme. Graphic design: BOOM s.r.o. Translation: Mánes překlady a tlumočení The following organizations are involved in the “SGDs and Migration” project, managed by Diaconia of ECCB: Global Call to Action Against Poverty (Belgium), Bulgarian Platform for International Development (Bulgaria), Federazione Organismi Cristiani Servizio Internazionale Volontario (Italy), ActionAid Hellas (Greece), Ambrela (Slovakia) and Povod (Slovenia). 1 POLICY PAPER The humanitarian situation in Syria, and its regional and global dimension With the Syrian crisis about to enter its 10th year, the humanitarian situation in Syria and in the neighbouring con- tinues to be critical. Despite the fact that in some areas of Syria the situation has largely stabilized, in Northwest and Northeast Syria there is the potential for a further escalation. There are risks of new displacements and increased humanitarian needs of a population already affected by years of conflict and depletion of resources, as witnessed in recent months as a result of the Operation Peace Spring in the Northeast and the ongoing Gov- ernment of Syria (GoS) and Government of Russia (GoR) offensive in the Northwest. -

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – March 2018 Page 1

Aid in Danger Aid agencies Monthly News Brief March 2018 Insecurity affecting the delivery of aid Security Incidents and Access Constraints This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of Africa violence affecting the delivery Central African Republic of aid. It is prepared by 05 March 2018: In Paoua town, Ouham-Pendé prefecture, and across Insecurity Insight from the wider Central African Republic, fighting among armed groups information available in open continues to stall humanitarian response efforts. Source: Devex sources. 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, rumours of All decisions made, on the basis an armed attack in the city forced several unspecified NGOs to of, or with consideration to, withdraw. Source: RJDH such information remains the responsibility of their 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, protesters at respective organisations. a women’s march against violence in the region called for the departure of MINUSCA and the Moroccan UN contingent from Editorial team: Bangassou, accusing them of passivity in the face of threats and Christina Wille, Larissa Fast and harassment. Source: RJDH Laurence Gerhardt Insecurity Insight 09 or 11 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, armed men suspected to be from the Anti-balaka movement invaded the Andrew Eckert base of the Dutch NGO Cordaid, looting pharmaceuticals, work tools, European Interagency Security motorcycles and seats. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Forum (EISF) Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) personnel intervened, leading to a firefight between MINUSCA and the armed Research team: men. The perpetrators subsequently vandalised the local Médecins James Naudi Sans Frontières (MSF) office. Cars, motorbikes and solar panels Insecurity Insight belonging to several NGOs in the area were also stolen. -

Syria Regional Program Ii Final Report

SYRIA REGIONAL PROGRAM II FINAL REPORT November 2, 2020 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. SYRIA REGIONAL PROGRAM II FINAL REPORT Contract No. AID-OAA-I-14-00006, Task Order No. AID-OAA-TO-15-00036 Cover photo: Raqqa’s Al Naeem Square after rehabilitation by an SRP II grantee. (Credit: SRP II grantee) DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................................ iv Executive Summary and Program Overview ..................................................... 1 Program Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. Country Context ................................................................................................. 3 A. The Regime’s Reconquest of Western Syria with Russian and Iranian Support ........ 3 B. The Territorial Defeat of ISIS in Eastern Syria ................................................................... 5 C. Prospects for the Future ......................................................................................................... 7 II. Program Operations ......................................................................................... 8 A. Operational -

The Axis Advances

wh07_te_ch17_s02_MOD_s.fm Page 568 Monday, March 12, 2007 2:32WH07MOD_se_CH17_s02_s.fm PM Page 568 Monday, January 29, 2007 6:01 PM Step-by-Step German fighter plane SECTION Instruction 2 WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO Objectives Janina’s War Story As you teach this section, keep students “ It was 10:30 in the morning and I was helping my focused on the following objectives to help mother and a servant girl with bags and baskets as them answer the Section Focus Question they set out for the market. Suddenly the high- and master core content. pitch scream of diving planes caused everyone to 2 freeze. Countless explosions shook our house ■ Describe how the Axis powers came to followed by the rat-tat-tat of strafing machine control much of Europe, but failed to guns. We could only stare at each other in horror. conquer Britain. Later reports would confirm that several German Janina Sulkowska in ■ Summarize Germany’s invasion of the the early 1930s Stukas had screamed out of a blue sky and . Soviet Union. dropped several bombs along the main street— and then returned to strafe the market. The carnage ■ Understand the horror of the genocide was terrible. the Nazis committed. —Janina Sulkowska,” Krzemieniec, Poland, ■ Describe the role of the United States September 12, 1939 before and after joining World War II. Focus Question Which regions were attacked and occupied by the Axis powers, and what was life like under their occupation? Prepare to Read The Axis Advances Build Background Knowledge L3 Objectives Diplomacy and compromise had not satisfied the Axis powers’ Remind students that the German attack • Describe how the Axis powers came to control hunger for empire.