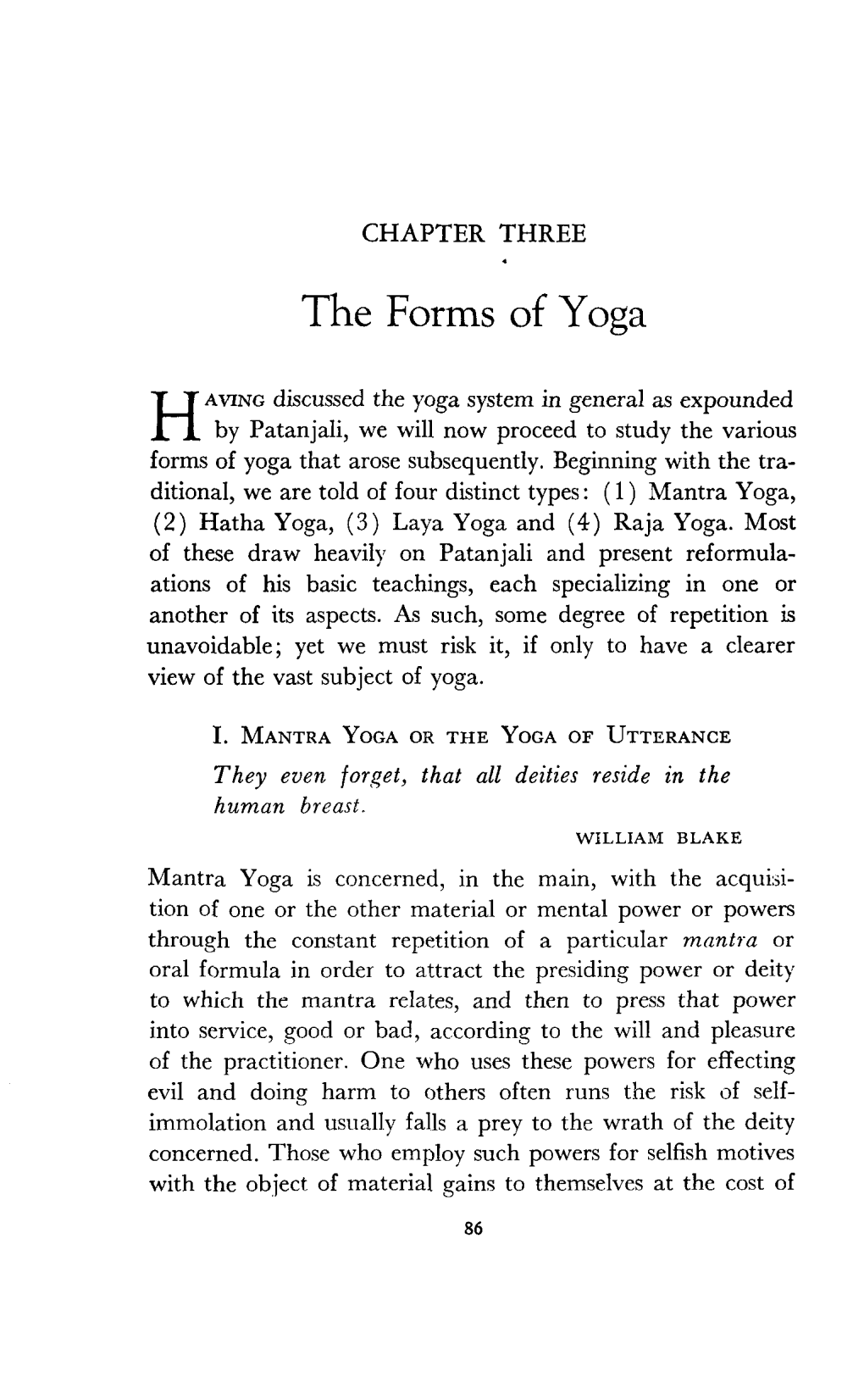

The Forms of Yoga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Downloaded License

philological encounters 6 (2021) 15–42 brill.com/phen Vision, Worship, and the Transmutation of the Vedas into Sacred Scripture. The Publication of Bhagavān Vedaḥ in 1970 Borayin Larios | orcid: 0000-0001-7237-9089 Institut für Südasien-, Tibet- und Buddhismuskunde, Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract This article discusses the first Indian compilation of the four Vedic Saṃhitās into a printed book in the year 1971 entitled “Bhagavān Vedaḥ.” This endeavor was the life’s mission of an udāsīn ascetic called Guru Gaṅgeśvarānand Mahārāj (1881–1992) who in the year 1968 founded the “Gaṅgeśvar Caturved Sansthān” in Bombay and appointed one of his main disciples, Svāmī Ānand Bhāskarānand, to oversee the publication of the book. His main motivation was to have a physical representation of the Vedas for Hindus to be able to have the darśana (auspicious sight) of the Vedas and wor- ship them in book form. This contribution explores the institutions and individuals involved in the editorial work and its dissemination, and zooms into the processes that allowed for the transition from orality to print culture, and ultimately what it means when the Vedas are materialized into “the book of the Hindus.” Keywords Vedas – bibliolatry – materiality – modern Hinduism – darśana – holy book … “Hey Amritasya Putra—O sons of the Immortal. Bhagwan Ved has come to give you peace. Bhagwan Ved brings together all Indians and spreads the message of Brotherhood. Gayatri Maata is there in every state of India. This day is indeed very auspicious for India but © Borayin Larios, 2021 | doi:10.1163/24519197-bja10016 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

Sivananda's Integral Yoga

SIVANANDA'S INTEGRAL YOGA By Siva-Pada-Renu SWAMI VENKATESANANDA 6(59(/29(*,9( 385,)<0(',7$7( 5($/,=( So Says Sri Swami Sivananda Sri Swami Venkatesananda A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION Seventh Edition: 1981 (2000 Copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Edition : 1998 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. PRAYERFUL DEDICATION TO BHAGAVAN SIVANANDA Lord! Condescend to accept this humble flower, fragrant with the aroma of thine own divine glory, immeasurable and infinite. Hundreds of savants and scholars might write hundreds of tomes on your glory, yet it would still transcend them all. In accordance with thine ancient promise: yada yada hi dharmasya glanir bhavati bharata abhyutthanamadharmasya tadatmanam srijamyaham paritranaya sadhoonam vinasaya cha dushkritam dharmasamsthapanarthaya sambhavami yuge yuge (Gita IV–7, 8) You, the Supreme Being, the all-pervading Sat-chidaranda-Para-Brahman, have taken this human garb and come into this world to re-establish Dharma (righteousness). The wonderful transformation you have brought about in the lives of millions all over the world is positive proof of your Divinity. I am honestly amazed at my own audacity in trying to bring this Supreme God, Bhagavan Sivananda, to the level of a human being (though Sage Valmiki had done so while narrating the story to Lord Rama) and to describe the Yoga of the Yogeshwareshwara, the goal of all Yogins. Lord! I cling to Thy lotus-feet and beg for Thy merciful pardon. -

Hindu Students Organization Sanātana Dharma Saṅgha

Hindu Students Organization Sanātana Dharma Saṅgha Table of Contents About HSO 1 Food for Thought 2 Pronunciation Guide 3 Opening Prayers 4 Gaṇesh Bhajans 6 Guru and Bhagavān Bhajans 9 Nārāyaṇa Bhajans 11 Krishṇa Bhajans 13 Rāma Bhajans 23 Devī Bhajans 27 Shiva Bhajans 32 Subramaṇyam Bhajans 37 Sarva Dharma Bhajans 38 Traditional Songs 40 Aartīs 53 Closing Prayers 58 Index 59 About HSO Columbia University’s Hindu Students Organization welcomes you. The Hindu Students Organization (HSO) is a faith-based group founded in 1992 with the intent of raising awareness of Hindu philosophies, customs, and traditions at Columbia University. HSO's major goals are to encourage dialogue about Hinduism and to provide a forum for students to practice the faith. HSO works with closely with other organizations to host joint events in an effort to educate the general public and the Columbia community. To pursue these goals, HSO engages in educational discussions, takes part in community service, and coordinates religious and cultural events including the following: Be the Change Day Navaratri Diwali Saraswati/Ganesh Puja Study Breaks Lecture Events Shruti: A Classical Night Holi Weekly Bhajans and Discussion Circle/Bhajans Workshop Interfaith Events Interviews to become a part of HSO’s planning board take place at the start of the fall semester. If you are interested in joining our mailing list or if you would like to get in touch with us, email us at [email protected] or visit us at http://www.columbia.edu/cu/hso/! 1 Food For Thought Om - “OM - This Imperishable Word is the whole of this visible universe. -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything. -

Buddhacarita

CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY Life of the Buddka by AsHvaghosHa NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS & JJC EOUNDATION THE CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JOHN & JENNIFER CLAY GENERAL EDITORS RICHARD GOMBRICH SHELDON POLLOCK EDITED BY ISABELLE ONIANS SOMADEVA VASUDEVA WWW.CLAYSANSBCRITLIBRARY.COM WWW.NYUPRESS.ORG Copyright © 2008 by the CSL. All rights reserved. First Edition 2008. The Clay Sanskrit Library is co-published by New York University Press and the JJC Foundation. Further information about this volume and the rest of the Clay Sanskrit Library is available at the end of this book and on the following websites: www.ciaysanskridibrary.com www.nyupress.org ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) Artwork by Robert Beer. Typeset in Adobe Garamond at 10.2$ : 12.3+pt. XML-development by Stuart Brown. Editorial input from Linda Covill, Tomoyuki Kono, Eszter Somogyi & Péter Szântà. Printed in Great Britain by S t Edmundsbury Press Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on acidffee paper. Bound by Hunter & Foulis, Edinburgh, Scotland. LIFE OF THE BUDDHA BY ASVAGHOSA TRANSLATED BY PATRICK OLIVELLE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS JJC FOUNDATION 2008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Asvaghosa [Buddhacarita. English & Sanskrit] Life of the Buddha / by Asvaghosa ; translated by Patrick Olivelle.— ist ed. p. cm. - (The Clay Sanskrit library) Poem. In English and Sanskrit (romanized) on facing pages. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Gautama Buddha-Poetry. I. Olivelle, Patrick. II. -

Šrî Sâi Leela

ŠRÎ SÂI LEELA Šrî Shirdi Sai Bâbâ Temple 1449 & 1451 Abers Creek Road, Monroeville, PA 15146 Mailing: PO Box 507 , Monroeville, PA 15146-0507 Phone: 412-374-9244 Fax: 412-374-0940 Website: http://www.baba.org “Help Ever, Hurt Never” Like us - www.facebook.com/pittsburghbabatemple Febuary 2015 “Saburi (patience) ferries you across to the distant goal. ”- Šrî Sâi Bâbâ.” CALENDAR OF EVENTS - Febuary 2015 MAHA SIVARATRI Celebrations - 15th - 17th Magham till Feb 18 Phalgunam Magha Krishna Chatursdasi - MAHA SIVARATRI Feb 2 Mon Magh Sukla Poornima - Maha Maghi 6.30pm Sâi Satyanârâyaña Vratam $54 7.30pm Jyoti Arati $108 Sri Sai Rudra Yagnam Feb 3 Tues 9.30am Ekavara Rudra Abhishekam $36 Saturday Jan 24th - Saunday Feb 15th ,2015 10am Mahalakshmi Homam $126 Sunday 15th - 12 noon Maha Poornahuthi Gift of woolen Shawl (Kambali) and a brass and copper alloy vessel filled with til or ghee is suggested for removal of obstacles in spiritual growth Monday 16th - Soma Pradosham Feb 7 Sat Magha Krishna (Sankatahara)Chaturthi 6.30 pm -Ekavara Rudra Abhishekam 10:00 am Ganapathi Abhishekam $54 Tuesday , Feb 17th - Maha Sivaratri 11:00 am Ganapathi Homam $126 8am Mahanyasa Purvaka Ekadasa Rudram 6:30 pm “GA” kara Sahasram $36 5pm Bilva Sahasranamam Feb 8 Sun Samohika Sri Sai Rudra Abhishekam 7pm Sri Sai Siva Bhajans 9.30am (individual Siva lingas will be given) $36 7.30pm Sej & Dinner Prasadam Jyothi arathi 10.30 am Sri Sai Navagraha Homam $252 Sri Sai Archana $11 / 5 pm Sahasranamam $21 Saturday Feb 21st-10.30pm Sri Siva Parvathi Kalyanam Feb 12 Thu Kumbha Sankramanam 7.45 pm Veda Patanam $21 All Devotees are invited to participate in the 3 day Feb 16 Mon Magha Krishna Trayodasi - SOMA PRADOSHAM celebrations of Maha Sivaratri in the Temple. -

Influence of Vishnusmriti in Sankardevas

International Journal of Applied Research 2020; 6(9): 355-357 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Influence of Vishnusmriti in Sankardevas Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2020; 6(9): 355-357 “Eka-Saran-Hari-Nama Dharma” www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 19-07-2020 Accepted: 25-08-2020 Durgeswar Kalita Durgeswar Kalita Asstt. Teacher, Abstract Rangia H.S. School, Dharmasastra is a collection of ancient Sanskrit texts which gives the codes of conduct and moral Rangia, Assam, India principles of dharma, for sanatana dharma. Dharmasastras are the sacred law books which prescribe moral laws and principles for religion. There are eighteeen dharmasastras or smritisastras in sanatana religion. Some important of them are- Yajnavalkya smriti, Vishnusmriti, parasara smriti, Gautamasmriti and Naradasmriti etc. These are sacred literature based on human memory as distinct from the vedas, which are considered to be shruti, literary “What is heard or the product of divine revelation most modern Hindus, however, have a greater familarity with these smriti scriptures. In the North East i.e. Assam Sankaradeva preached the eka-sarana-hari-nama-dharma. Sankardeva studied various Hindu scriptures- Fourvedas, all philosophical scriptures, fourteen sastras,all puranas, dharmasastras i.e. smritisastras also. Sankardeva basically brought the essance of Vishnubhakti from Vishnusmriti to preach his hari-nama-dharma. Vishnusmriti has a strong bhakti orientation requering daily aradhana to the God Vishnu. The Vishnusmriti is divided into one hundred chapters, consisting mostly of prose text but including one or more verses at the end of each chapter. Vishnusmriti is called the Vaishnava dharmasastra. Keywords: vishnusmriti, sankardevas, eka-saran-hari-nama dharma Introduction Dharmasastra is a collection of ancient Sanskrit texts which gives the codes of conduct and moral principles of dharma, for sanatana dharma. -

Yogrishi Vishvketu Himalayan Yoga Master and Co-‐‑Founder of Akhanda Yoga, Yogris

Yogrishi Vishvketu Himalayan Yoga Master and Co-founder of Akhanda Yoga, Yogrishi Vishvketu (Vishva-ji) is known for his infectious laughter, playfulness and stories. His holistic approach brings forward ancient wisdom for a modern age, incorporating asana, pranayama, mantra, meditation and yogic wisdom in every class. Vishva-ji’s deepest aim is to inspire people to connect to their true nature, which is joyful, fearless, expansive and playful. A Yogi at heart, Vishva-ji has studied and practiced Yoga in the Himalayas since the age of 8 and holds a PhD in Yoga Philosophy. He has since trained thousands of teachers through his Yoga Alliance registered 200- and 300-hour Yoga Teacher Training (YTT) programs in Rishikesh, India, and teaches at workshops and conferences internationally. He continues his father’s legacy of charitable works in local communities. In 2007, Vishva-ji co-founded Anand Prakash Yoga Ashram Trust in Rishikesh. In 2013, he founded Sansar Gyaan Pathshala, a free school for over two hundred and fifty underserved children in rural Uttar Pradesh, India, which is supported by the Canadian charity Helping Hands for India. Yogrishi Vishvketu is the author of Yogasana: The Encyclopedia of Yoga Poses, (Mandala Earth, 2015) and is currently working on his next book. To learn more about trainings and retreats, please visit: www.akhandayoga.com To join his online yoga platform with hundreds of Akhanda Yoga classes you can practice in your own home, visit: www.akhandayogaonline.com On Social Media: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/yogrishivishvketu https://www.facebook.com/akhandayoga.yv YouTube: www.YouTube.com/akhandayoga Twitter: @YogiVishvketu Instagram: @vishva.ji and @akhanda_yoga . -

Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary Books on the Related Theme by the Same Author

Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary Books on the related theme by the Same Author ● Hinduism: A Gandhian Perspective (2nd Edition) ● Ethics for Our Times: Essays in Gandhian Perspective Handbook of Hinduism Ancient to Contemporary M.V. NADKARNI Ane Books Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi ♦ Chennai ♦ Mumbai Kolkata ♦ Thiruvananthapuram ♦ Pune ♦ Bengaluru Handbook of Hinduism: Ancient to Contemporary M.V. Nadkarni © Author, 2013 Published by Ane Books Pvt. Ltd. 4821, Parwana Bhawan, 1st Floor, 24 Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002 Tel.: +91(011) 23276843-44, Fax: +91(011) 23276863 e-mail: [email protected], Website: www.anebooks.com Branches Avantika Niwas, 1st Floor, 19 Doraiswamy Road, T. Nagar, Chennai - 600 017, Tel.: +91(044) 28141554, 28141209 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Gold Cornet, 1st Floor, 90 Mody Street, Chana Lane, (Mohd. Shakoor Marg), Opp. Masjid, Fort Mumbai - 400 001, Tel.: +91(022) 22622440, 22622441 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Flat No. 16A, 220 Vivekananda Road, Maniktala, Kolkata - 700 006, Tel.: +91(033) 23547119, 23523639 e-mail: [email protected] # 6, TC 25/2710, Kohinoor Flats, Lukes Lane, Ambujavilasam Road, Thiruvananthapuram - 01, Kerala, Tel.: +91(0471) 4068777, 4068333 e-mail: [email protected] Resident Representative No. 43, 8th ‘‘A’’ Cross, Ittumadhu, Banashankari 3rd Stage Bengaluru - 560 085, Tel.: +91 9739933889 e-mail: [email protected] 687, Narayan Peth, Appa Balwant Chowk Pune - 411 030, Mobile: 08623099279 e-mail: [email protected] Please be informed that the author and the publisher have put in their best efforts in producing this book. Every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the contents. -

Mind-Management-And-Human-Values-2016.Pdf

VISHVA- CHAITANYA An experiential course on MIND MANAGEMENT AND HUMAN VALUES FOR 1st year Degree Students, Jain University Conducted by Human Networking Academy JAIN UNIVERSITY EDITORIAL BOARD Prof. K.S.Shantamani Chief Mentor, Jain University Prof. K Raghothama Rao TNC Col. Vijayasarathy VSM Director Chief Programme Co-ordinator Abhijith Shenoy K Smitha Kashi Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Sushma Kashi Sujith K Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Swaroop R Sumithra Radhakrishnan Lecturer Visiting Faculty MESSAGE Dear Faculty & Students, It is heartening to know that the Human Networking Academy, a distinguished division of the Jain Group of Institutions (JGI), has prepared a course entitled Mind Management and Human Values along with suitable course materials to be included in the Jain University undergraduate programmes. I congratulate the members of the HNA for their invaluable experience, meticulous planning and tremendous energy for such a course, a reality in a very short time. In these days of globalization it is extremely difficult to convince the students the need for and the importance of keeping their minds serene unpolluted and open so as to enable them to realize the full potential of their mental faculties. With a view to equipping the students with the requisite knowledge and skills to strengthen their mind, the Jain University has introduced a course entitled Mind Management and Human Values in its undergraduate course curriculum. I am happy to place on record my appreciation for Prof. K.S. Shantamani, Chief Mentor of JGI for planning the course and taking all the trouble to inculcate human, spiritual and ethical values in our students and her commitment and dedication.