Intratextual Baudelaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW OCTOBER 1961 Death of General Lyon, Battle of Wilson's Creek Published Quarte e State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1959-1962 E. L. DALE, Carthage, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President WILLIAM L. BKADSHAW, Columbia, Second Vice President GEORGE W. SOMERVILLE, Chillicothe, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director. Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City L. M. WHITE, Mexico G. L. ZWICK. St Joseph Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1961 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED 0. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1962 F C. BARNHILL, Marshall *RALPH P. JOHNSON, Osceola FRANK P. BRIGGS Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. Louis HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville Term Expires at Annual Meeting. 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. -

Baudelaire 525 Released Under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence

Table des matières Préface i Préface des Fleurs . i Projet de préface pour Les Fleurs du Mal . iii Preface vi Preface to the Flowers . vi III . vii Project on a preface to the Flowers of Evil . viii Préface à cette édition xi L’édition de 1857 . xi L’édition de 1861 . xii “Les Épaves” 1866 . xii L’édition de 1868 . xii Preface to this edition xiv About 1857 version . xiv About 1861 version . xv About 1866 “Les Épaves” . xv About 1868 version . xv Dédicace – Dedication 1 Au Lecteur – To the Reader 2 Spleen et idéal / Spleen and Ideal 9 Bénédiction – Benediction 11 L’Albatros – The Albatross (1861) 19 Élévation – Elevation 22 Correspondances – Correspondences 25 J’aime le souvenir de ces époques nues – I Love to Think of Those Naked Epochs 27 Les Phares – The Beacons 31 La Muse malade – The Sick Muse 35 La Muse vénale – The Venal Muse 37 Le Mauvais Moine – The Bad Monk 39 L’Ennemi – The Enemy 41 Le Guignon – Bad Luck 43 La Vie antérieure – Former Life 45 Bohémiens en voyage - Traveling Gypsies 47 L’Homme et la mer – Man and the Sea 49 Don Juan aux enfers – Don Juan in Hell 51 À Théodore de Banville – To Théodore de Banville (1868) 55 Châtiment de l’Orgueil – Punishment of Pride 57 La Beauté – Beauty 60 L’Idéal – The Ideal 62 La Géante – The Giantess 64 Les Bijoux – The Jewels (1857) 66 Le Masque – The Mask (1861) 69 Hymne à la Beauté – Hymn to Beauty (1861) 73 Parfum exotique – Exotic Perfume 76 La Chevelure – Hair (1861) 78 Je t’adore à l’égal de la voûte nocturne – I Adore You as Much as the Nocturnal Vault.. -

Íbúum Á Laugavegi Hótað Dagsektum

Berglind Ágústsdóttir lh hestar ræktaði hæst dæmda íslenska stóðhestinn ÍÞRÓTT • MENNING • LÍFSSTÍLL BLS. 6 ÞRIÐJUDAGUR 20. MAÍ 2008 Gæðingum á Þrír fá alþjóðleg LM fjölgar dómararéttindi GARÐAR THOR CORTES Nú liggja fyrir félagatöl hesta- Þrír íslenskir hestaíþrótta dómarar mannafélaganna fyrir árið 2008. fengu alþjóðleg dómararéttindi Sumarblóm fer að Sjóvá kvennahlaup ÍSÍ mun Vatn er lífsnauðsynlegt Fjöldi þátttakenda frá hverju fé- á dómararáðstefnu FEIF sem verða tímabært að gróð- fara fram í nítjánda sinn og hollasti svaladrykk- lagi á LM2008 miðast við þau. Tölu- var haldin á Hvanneyri 11. til 13. ursetja í garðinn. Blóm- laugardaginn 7. júní í urinn. Það hentar vel á verð fjölgun hefur orðið í félögun- apríl. Alls tóku 48 dómarar þátt í legt og fagurt umhverfi samstarfi við Lýðheilsu- milli mála og skemmir um og þar með fjöldi hrossa sem ráðstefnunni, þar af ellefu frá Ís- er gott fyrir heilsuna og stöð og er því kjörið að ekki tennur og er því gott hvar er betra að slaka á byrja að þjálfa sig og fara að hafa ætíð vatn við þau hafa rétt til að senda til þátt- landi. Eftir ráðstefnuna var haldið en í fallegum og friðsæl- út að skokka. Bolurinn í ár höndina. töku. Á LM2006 voru 112 í hverj- nýdómarapróf og stóðust þrír ís- um garði sem prýddur er er fjólublár og er þema ársins um flokki en á LM2008 eiga 119 lenskir dómarar prófið: Elísabeth dýrindis gróðri? Ef fólk er ekki „Heilbrigt hugarfar, hraustar þátttökurétt. Alls sendu félögin Jansen, Hulda G. Geirsdóttir og svo heppið að eiga garð má alltaf fá sér konur“. -

The Janus-Faced Dilemma of Rock Art Heritage

The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon To cite this version: Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Taylor & Francis, In press, 10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329. hal-03078965 HAL Id: hal-03078965 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03078965 Submitted on 21 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Duval Mélanie, Gauchon Christophe, 2021. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329 Authors: Mélanie Duval and Christophe Gauchon Mélanie Duval: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France; * Rock Art Research Institute GAES, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Christophe Gauchon: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France. -

2008-09 an Eclectic Collection of Words

A Burnaby School District Publication, An Eclectic Collection of Words represents the best in student writing from Burnaby’s WORDS Writing Project for 2008/09. An Eclectic Cover art by Burnaby South Secondary grade 12 student Min Kyong Song. Collection of Words Thank you to our sponsors for their continued support: 2008/09 ANTHOLOGY Burnaby’s WORDS Writing Project includes creative writing submissions from K-12 students throughout the district. With no theme provided, the topics are endless – from stories of adventure to journeys of introspection, from lighthearted poetry to verse that is poignant in its insight. Their submissions are reviewed by a panel of judges with a background in writing and communications. They are grouped according to age or grade, while the students name and school remain anonymous. Submissions from the following students were selected for publication in the 2008/09 WORDS Anthology, An Eclectic Collection of Words , to showcase the talent of Burnaby’s aspiring young writers. Ages 5-7 ______________________________________________ Poetry Olivia Hu Clinton Elementary My Secret Friend Eric Lee Buckingham Elementary Winter Matthew Chin Clinton Elementary Before Time Marlon Buchanan Clinton Elementary Cookie Matthew Chiang Buckingham Winter Poetry – French Ryan Jinks Aubrey Elementary La Neige Sophia Moreira Sperling Elementary Les Fleurs Prose Ella White Parkcrest Elementary Hearts Isabelle Cosacescu Clinton Elementary The Missing Cat Carymnn Skalnik Clinton Elementary The Adventure in the Snow Prose - French Henry -

Scapigliatura

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Baudelairism and Modernity in the Poetry of Scapigliatura Alessandro Cabiati PhD The University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract In the 1860s, the Italian Scapigliati (literally ‘the dishevelled ones’) promoted a systematic refusal of traditional literary and artistic values, coupled with a nonconformist and rebellious lifestyle. The Scapigliatura movement is still under- studied, particularly outside Italy, but it plays a pivotal role in the transition from Italian Romanticism to Decadentism. One of the authors most frequently associated with Scapigliatura in terms of literary influence as well as eccentric Bohemianism is the French poet Charles Baudelaire, certainly amongst the most innovative and pioneering figures of nineteenth-century European poetry. Studies on the relationship between Baudelaire and Scapigliatura have commonly taken into account only the most explicit and superficial Baudelairian aspects of Scapigliatura’s poetry, such as the notion of aesthetic revolt against a conventional idea of beauty, which led the Scapigliati to introduce into their poetry morally shocking and unconventional subjects. -

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

Word for Word Parola Per Parola Mot Pour Mot

wort für wort palabra por palabra word for word parola per parola mot pour mot 1 word for word wort für wort palabra por palabra mot pour mot parola per parola 2015/2016 2 table of contents foreword word for word / wort für wort Columbia University School of the Arts & Deutsches Literaturinstitut Leipzig 6 word for word / palabra por palabra Columbia University School of the Arts & New York University MFA in Creative Writing in Spanish 83 word for word / parola per parola Columbia University School of the Arts & Scuola Holden 154 word for word / mot pour mot Columbia University School of the Arts & Université Paris 8 169 participating institutions 320 acknowledgements 4 foreword Word for Word is an exchange program that was conceived in 2011 by Professor Binnie Kirshenbaum, Chair of the Writing Program of Columbia University’s School of the Arts, in the belief that that when writers engage in the art of literary transla- tion and collaborate on translations of each other’s work, the experience will broad- en and enrich their linguistic imaginations. Since 2011, the Writing Program conducted travel-based exchanges in partnership with the Deutsches Literaturinstitut Leipzig in Leipzig, Germany; the Scuola Holden in Turin, Italy; the Institut Ramon Llull and Universitat Pompeu Fabra–IDEC in Barcelona, Catalonia (Spain); the Columbia Global Center | Middle East in Amman, Jordan; Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C.; and the University of the Arts Helsinki in Helsinki, Finland. Starting in 2016, the Word for Word program expanded to include a collaborative translation workshop running parallel to the exchanges, in which Writing Program students, over the course of one semester, translate work by their partners at some of these same institutions – the Deutsches Literaturinstitut Leipzig and Scuola Holden–as well as some new ones: Université Paris 8 in Paris, France; New York University’s Creative Writing in Spanish MFA Program; and the Instituto Vera Cruz in São Paulo, Brazil. -

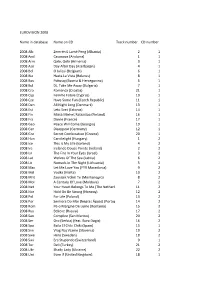

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

The Works an D Life of Walter Bagehot

THE WORKS AN D LIFE OF WALTER BAGEHOT VOL. III. THE WORKS AND LIFE OF WALTER BAGEHOT EDItED BY MRS. RUSSELL BARRINGTON THE WORKS J.1'; NI.1';E VOLUME:" THE LIFE IN ONE VOLU~IE VOL. III. OF THE WORKS LON G MAN S, G R E EN, AND C O. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON FOURTH AVENUE & 30TH :"TREET, NEW YORK BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAr" CONTENTS OF VOLUME III. PAOi BERANGER (1857) THE WAVERLEY NOVELS (1858) 37 CHARLES DICKENS (1858) 73 PARLIAMENTARY REFORM (1859) 108 JOHN MILTON (1859) • THE HISTORY OF THE UNREFORMED PARLIAMENT, AND ITS LESSONS (1860) • 222 MR. GLADSTONE (1860) 272 MEMOIR OF THE RIGHT HONOURABLE JAMES WILSON (1850) . 302 THE AMERICAN CONSTITUTION AT THE PRESENT CRISIS. Causes of the Civil War in America. By j. Lothrop Motley Manwaring (from Na- tIonal Review, October, 1861) 349 v ERRATA. Page 378, line 14,jor eight read eighth 379, " 7,,, member read minister BERANGER.l THE invention of books has at least one great advantage. It has half-abolished one of the worst consequences of the diver- sity of languages. Literature enables nations to understand one another. Ora) intercourse hardly does this. In English, a distinguished foreigner says not what he thinks, but what he can. There is a certain intimate essence of national mean- ing which is as untranslatable as good poetry. Dry thoughts are cosmopolitan; but the delicate associations of language which express character, the traits of speech which mark the man, differ in every tongue, so that there are not even cum- brous circumlocutions that are equivalent in another. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Les Espaces De L'autonomie Des Préadolescents

Les espaces de l’autonomie des préadolescents. Une comparaison franco-allemande du processus d’individualisation François de Singly avec Karine Chaland Ministère de l’Equipement, des Transports et du Logement Plan Urbanisme Construction et Architecture Pôle Sociétés urbaines, habitat et territoires Consultation de recherche, Habitat et vie urbaine Notification de subvention de recherche (APSROM 32 00 01) Septembre 2003 Remerciements Cette recherche n’a été possible que grâce au soutien et au travail de nombreuses personnes, et institutions. Tout d’abord elle a bénéficié de la confiance accordée par le Plan Urbanisme, Construction, Architecture (du Ministère de l’équipement, des transports et du logement) dans le cadre de la consultation « Habitat et vie urbaine » , notamment par Claire Gillio, Colette Joseph. Karine Chaland a eu la responsabilité du « terrain » dans les deux pays. Elle a, en outre, assuré la quasi-totalité des entretiens à Strasbourg – à l’exception de deux entretiens, effectués par Olivier Wendling – à Berlin et à Fribourg. Frank Welz, sociologue, a organisé l’essentiel des contacts avec Fribourg et Berlin. La quasi-totalité des entretiens de Paris ont été menés par Yaëlle Emsellem et Benoît Chazot qui les ont également retranscrits ; quelques entretiens complémentaires ont été réalisés par Karine Chaland. Plusieurs personnes, ou institutions, ont collaboré à cette recherche en servant de relais, d’intermédiaires entre les préadolescents et les enquêteurs. Parmi eux, citons pour Strasbourg, Mme Zora Bekkouche du Centre socio-culturel de la Robertsau, Mme Marie-Pierre Lefebvre du Centre socio-culturel de Koenigshoffen, Mme Lafon de la PEEP, Mme Elisa Terrier de l’UNAF, Mr Gérald Klein de l’AFEV, Mr Yohan Abitbol de l’ARES pour Strasbourg.