Towards a Comparative Montage of the Female Portrait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

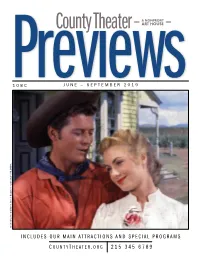

County Theater ART HOUSE

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

Index of Authors

Index of Authors Abel, Richard 19, 20, 134, 135, 136, Alexander, David 441 Andre, Marle 92 Aros (= Alfred Rosenthal) 196, 225, 173 Alexander, lohn 274 Andres, Eduard P. 81 244, 249, 250 Abel, Viktor 400 Alexander, Scott 242, 325 Andrew, Geoff 4, 12, 176, 261,292 Aros, Andrew A. 9 Abercrombie, Nicholas 446 Alexander, William 73 Andrew, 1. Dudley 136, 246, 280, Aroseff, A. 155 Aberdeen, l.A. 183 Alexowitz, Myriam 292 330, 337, 367, 368 Arpe, Verner 4 Aberly, Rache! 233 Alfonsi, Laurence 315 Andrew, Paul 280 Arrabal, Fernando 202 About, Claude 318 Alkin, Glyn 393 Andrews, Bart 438 Arriens, Klaus 76 Abramson, Albert 436 Allan, Angela 6 Andrews, Nigel 306 Arrowsmith, William 201 Abusch, Alexander 121 Allan, Elkan 6 Andreychuk, Ed 38 Arroyo, lose 55 Achard, Maurice 245 Allan, Robin 227 Andriopoulos, Stefan 18 Arvidson, Linda 14 Achenbach, Michael 131 Allan, Sean 122 Andritzky, Christoph 429 Arzooni, Ora G. 165 Achternbusch, Herbert 195 Allardt-Nostitz, Felicitas 311 Anfang, Günther 414 Ascher, Steven 375 Ackbar, Abbas 325 Allen, Don 314 Ang, Ien 441, 446 Ash, Rene 1. 387 Acker, Ally 340 Allen, Jeanne Thomas 291 Angelopoulos, Theodoros 200 Ashbrook, lohn 220 Ackerknecht, Erwin 10, 415, 420 Allen, lerry C. 316 Angelucci, Gianfranco 238 Ashbury, Roy 193 Ackerman, Forrest }. 40, 42 Allen, Michael 249 Anger, Cedric 137 Ashby, lustine 144 Acre, Hector 279 Allen, Miriam Marx 277 Anger, Kenneth 169 Ashley, Leonard R.N. 46 Adair, Gilbert 5, 50, 328 Allen, Richard 254, 348, 370, 372 Angst-Nowik, Doris ll8 Asmus, Hans-Werner 7 Adam, Gerhard 58, 352 Allen, Robert C. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames

Online Course: Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames WRITTEN BY CHRIS GARCIA Welcome to Film Noir: Danger, Darkness and Dames! This online course was written by Chris Garcia, an Austin American-Statesman Film Critic. The course was originally offered through Barnes & Noble's online education program and is now available on The Midnight Palace with permission. There are a few ways to get the most out of this class. We certainly recommend registering on our message boards if you aren't currently a member. This will allow you to discuss Film Noir with the other members; we have a category specifically dedicated to noir. Secondly, we also recommend that you purchase the following books. They will serve as a companion to the knowledge offered in this course. You can click each cover to purchase directly. Both of these books are very well written and provide incredible insight in to Film Noir, its many faces, themes and undertones. This course is structured in a way that makes it easy for students to follow along and pick up where they leave off. There are a total of FIVE lessons. Each lesson contains lectures, summaries and an assignment. Note: this course is not graded. The sole purpose is to give students a greater understanding of Dark City, or, Film Noir to the novice gumshoe. Having said that, the assignments are optional but highly recommended. The most important thing is to have fun! Enjoy the course! Jump to a Lesson: Lesson 1, Lesson 2, Lesson 3, Lesson 4, Lesson 5 Lesson 1: The Seeds of Film Noir, and What Noir Means Social and artistic developments forged a new genre. -

Member Calendar MAR

Member Calendar MAR APR Mar–Apr 2019 “I never get over wondering at your prodigiousness,” MoMA founding director Alfred H. Barr Jr. mused admiringly to Lincoln Kirstein in 1945. Indeed, the extent of Kirstein’s influence on American culture in the 1930s and ’40s is hard to overstate. Best known for having cofounded, with the Russian choreographer George Balanchine, the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet, Kirstein was also a key figure in MoMA’s early history. Organizing exhibitions, writing catalogue essays, donating works to the Museum, and making acquisitions on its behalf, Kirstein championed a vision of modernism that favored figuration over abstraction and argued for an interdisciplinary marriage between the arts. Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern (Member Previews start March 13) invites you to rediscover rich areas of MoMA’s collection through the eyes of this impresario and tastemaker. The nearly 300 works on view include set and costume designs for the ballet; photography that explores American themes; sculpture that finds inspiration in folk art and classicism; finely rendered realist and magic-realist paintings; and the Latin American works that Kirstein purchased for the Museum in 1942. Some of these works might be old favorites, while others may represent new discoveries. The same is true for the Museum’s wide-ranging offerings this spring: the objects in The Value of Good Design may be things you use in your daily life; the paintings in Joan Miró: The Birth of the World may be familiar friends; while the recent acquisitions in New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century have mostly not been seen before. -

Thequadrangletimes FEBRUARY 2015 ISSUE Written and Produced by Quadrangle Residents

TheQuadrangleTimes FEBRUARY 2015 ISSUE Written and Produced by Quadrangle Residents OUR FOURTH ANNUAL OBSERVANCE OF MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. DAY THE CALVARY BAPTIST CHURCH CHOIR AND THE AMW MUSIC GROUP PRESENTED MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT, AND THE QUADRANGLE AUDIENCE JOINED IN FOR A SPIRITED FINALE, SINGING, “WE SHALL OVERCOME.” NEW RESIDENTS . WELCOME NEW RESIDENT LINDA COHEN Linda grew up in Brooklyn and graduated from Brooklyn College, where she majored in English. She married after college, and as her husband completed graduate work in different cities she attended college programs that interested her. When Linda and her husband lived in Providence, Rhode Island, she completed a master’s degree in teaching at Rhode Island College. Many years later when they lived in Lower Merion, she earned a second master’s degree in library science at Villanova University. For 15 years Linda worked as the librarian in the lower school of Episcopal Academy. She expanded the library’s role to function as a class with projects and report card grades. She developed assembly programs, bringing authors to talk about their books. Many years ago one of Linda’s daughters had a pen pal in Norway. By the time she finished college this friendship had blossomed into marriage. The couple lives south of Oslo, and over the years Linda has made 34 trips there to visit with them and her two grandchildren. Linda has another daughter and one grandchild who live in a Philadelphia suburb. For exercise Linda swims every morning for an hour and water walks for another hour. She has always enjoyed reading. -

Centrespread Centrespread 15 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016

14 centrespread centrespread 15 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016 OCTOBER 23-29, 2016 As the maximum city’s cinephiles flock to the 18th edition of the Mumbai Film Festival (October 20-27), organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image, ET Magazine looks at some of its most famous counterparts across the world and also in India Other Festivals in IndiaInddia :: G Seetharaman International Film Festivalstival of Kerala Begun in 1996, the festivalstival is believed to be betterter curated than its counterparts in thee Cannes Film Festival (Cannes, France) Venice Film Festival (Italy) country. It is organisedanised by the state governmenternment STARTED IN: 1946 STARTED IN: 1932 TOP AWARD: Palme d’Or (Golden Palm) TOP AWARD: Golden Lion and held annually in Thiruvananthapuram NOTABLE WINNERS OF TOP AWARD: Blow-Up, Taxi Driver, Apocalypse Now, Pulp Fiction, Fahrenheit 9/11 NOTABLE WINNERS OF TOP AWARD: Rashomon, Belle de jour, Au revoir les enfants, Vera Drake, Brokeback Mountain ABOUT: Undoubtedly the most prestigious of all film festivals, Cannes' top awards are second only to the Oscars in their Internationalnal FilmF Festival of India cachet. Filmmakers like Woody Allen, Wes Anderson and Pedro Almodovar have premiered their films at Cannes, which is ABOUT: Given Italy’s great filmmaking tradition — think Vittorio de Sica, as much about the business of films as their aesthetics; the distribution rights for the best of world cinema are acquired by Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni — it is no surprise that the Run jointly by the information and giants like the Weinstein Company and Sony Pictures Classics, giving them a real shot at country hosts one of the finest film festivals in the world. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 27 Dresses DVD-8204 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 28 Days Later DVD-4333 10th Victim DVD-5591 DVD-6187 12 DVD-1200 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 12 and Holding DVD-5110 3 Women DVD-4850 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 12 Monkeys DVD-3375 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 1776 DVD-0397 300 DVD-6064 1900 DVD-4443 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 1984 (Hurt) DVD-4640 39 Steps DVD-0337 DVD-6795 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 1984 (Obrien) DVD-6971 400 Blows DVD-0336 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 42 DVD-5254 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 50 First Dates DVD-4486 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 500 Years Later DVD-5438 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-0260 61 DVD-4523 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 70's DVD-0418 2012 DVD-4759 7th Voyage of Sinbad DVD-4166 2012 (Blu-Ray) DVD-7622 8 1/2 DVD-3832 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 8 Mile DVD-1639 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 9 to 5 DVD-2063 25th Hour DVD-2291 9.99 DVD-5662 9/1/2015 9th Company DVD-1383 Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet DVD-0831 A.I. -

Monday 25 July 2016, London. Ahead of Kirk Douglas' 100Th Birthday This

Monday 25 July 2016, London. Ahead of Kirk Douglas’ 100th birthday this December, BFI Southbank pay tribute to this major Hollywood star with a season of 20 of his greatest films, running from 1 September – 4 October 2016. Over the course of his sixty year career, Douglas became known for playing iconic action heroes, and worked with the some of the greatest Hollywood directors of the 1940s and 1950s including Billy Wilder, Howard Hawks, Vincente Minnelli and Stanley Kubrick. Films being screened during the season will include musical drama Young Man with a Horn (Michael Curtiz, 1949) alongside Lauren Bacall and Doris Day, Stanley Kubrick’s epic Spartacus (1960), Champion (Mark Robson, 1949) for which he received the first of three Oscar® nominations for Best Actor, and the sci- fi family favourite 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Richard Fleischer, 1954). The season will kick off with a special discussion event Kirk Douglas: The Movies, The Muscles, The Dimple; this event will see a panel of film scholars examine Douglas’ performances and star persona, and explore his particular brand of Hollywood masculinity. Also included in the season will be a screening of Seven Days in May (John Frankenheimer, 1964) which Douglas starred in opposite Ava Gardner; the screening will be introduced by English Heritage who will unveil a new blue plaque in honour of Ava Gardner at her former Knightsbridge home later this year. Born Issur Danielovich into a poor immigrant family in New York State, Kirk Douglas began his path to acting success on a special scholarship at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, where he met Betty Joan Perske (later to become better known as Lauren Bacall), who would play an important role in helping to launch his film career. -

Film Stars Don't Die in Liverpool

FILM STARS DON'T DIE IN LIVERPOOL Written by Matt Greenhalgh 1. 1 INT. LEADING LADY’S DRESSING ROOM - NIGHT 1 Snug and serene. An illuminated vanity mirror takes centre stage emanating a welcoming glamorous glow. A SERIES OF C/UP’s: A TDK AUDIO TAPE inserted into a slim SONY CASSETTE PLAYER immediately placing us in the late 70’s/early 80’s. A CHIPPED VARNISHED FINGER NAIL presses play.. ‘Song For Guy’ by Elton John (Gloria’s favourite track) drifts in... OUR LEADING LADY sits in the dresser. Find her through shards of focus and reflections as she transforms.. warming her vocal chords as she goes: GLORIA (O.C.) ‘La Poo Boo Moo..’ Eye-line pencil; cherry-red lipstick; ‘Saks of Fifth Avenue’ COMPACT MIRROR, intricately engraved with “Love Bogie ’In A Lonely Place’ 1950”; Elnett hair laquer; Chanel perfume. A larger BROKEN HAND-MIRROR. A GOLDEN LOVE HEART PENDANT (opens with a sychronised tune). All Gloria’s ‘tools’ procured from a TATTY GREEN WASH-BAG, a trusted witness to her ‘process’ probably a thousand times or more. GLORIA (O.C.) (CONT’D) ‘Major Mickey’s Malt Makes Me Merry.’ Costume: Peek at pale flesh and slim limbs as she climbs into a black, pleated wrap around dress with a plunging neckline; black stockings and princess slippers.. the dress hangs loose, too loose.. the belt tightened as far as it can go. A KNOCK ON THE DOOR STAGE MANANGER (V.O.) Five minutes Miss Grahame. GLORIA (O.C.) Thanks honey. Gloria’s tongue CLUCKS the roof of her mouth in approval, it’s one of her things. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953).