Observations on Van Dyck As a Religious Painter Thomas L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 10, Issue 02, 2021: 28-50 Article Received: 02-02-2021 Accepted: 22-02-2021 Available Online: 28-02-2021 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v10i2.2053 The Enthroned Virgin and Child with Six Saints from Santo Stefano Castle, Apulia, Italy Dr. Patrice Foutakis1 ABSTRACT A seven-panel work entitled The Monopoli Altarpiece is displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts. It is considered to be a Cretan-Venetian creation from the early fifteenth century. This article discusses the accounts of what has been written on this topic, and endeavors to bring field-changing evidence about its stylistic and iconographic aspects, the date, the artists who created it, the place it originally came from, and the person who had the idea of mounting an altarpiece. To do so, a comparative study on Byzantine and early-Renaissance painting is carried out, along with more attention paid to the history of Santo Stefano castle. As a result, it appears that the artist of the central panel comes from the Mystras painting school between 1360 and 1380, the author of the other six panels is Lorenzo Veneziano around 1360, and the altarpiece was not a single commission, but the mounting of panels coming from separate artworks. The officer Frà Domenico d’Alemagna, commander of Santo Stefano castle, had the idea of mounting different paintings into a seven-panel altarpiece between 1390 and 1410. The aim is to shed more light on a piece of art which stands as a witness from the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of Renaissance; as a messenger from the Catholic and Orthodox pictorial traditions and collaboration; finally as a fosterer of the triple Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance expression. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way. -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 196-212 brill.com/jjs Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art John Marciari The Morgan Library & Museum, New York [email protected] Abstract While Bernini and other artists of his generation would be responsible for much of the decoration at the Chiesa del Gesù and other Jesuit churches, there was more than half a century of art commissioned by the Jesuits before Bernini came to the attention of the order. Many of the early works painted in the 1580s and 90s are no longer in the church, and some do not even survive; even a major monument like Girolamo Muzia- no’s Circumcision, the original high altarpiece, is neglected in scholarship on Jesuit art. This paper turns to the early altarpieces painted for the Gesù by Muziano and Scipione Pulzone, to discuss the pictorial and intellectual concerns that seem to have guided the painters, and also to some extent to speculate on why their works are no longer at the Gesù, and why these artists are so unfamiliar today. Keywords Jesuit art – Il Gesù – Girolamo Muziano – Scipione Pulzone – Federico Zuccaro – Counter-Reformation – Gianlorenzo Bernini Visitors to the Chiesa del Gesù in Rome, or to the recent exhibition of Jesuit art at Fairfield University,1 might naturally be led to conclude that Gianlorenzo 1 Linda Wolk-Simon, ed., The Holy Name: Art of the Gesù; Bernini and His Age, Exh. cat., Fair- field University Art Museum, Early Modern Catholicism and the Visual Arts 17 (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph’s University Press, 2018). -

Nicolas Lancret: Dance Before a Fountain

NICOLAS LA1VCRET Dance Before a r~zfountain~ NICOLAS LA1VCRET Dance Before a r~Tfountain~ MARY TAVENER HOLMES WITH A CONSERVATION NOTE BY MARK LEONARD THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM LOS ANGELES This book is dedicated to Donald Posner GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © 2006 J. Paul Getty Trust Holmes, Mary Tavener. Nicolas Lancret : Dance before a fountain / Mary Tavener Holmes ; Getty Publications with a conservation note by Mark Leonard. I2OO Getty Center Drive, Suite 5OO p. cm. — (Getty Museum studies on art) Los Angeles, California ^004^^-1682 Includes bibliographical references and index. www.getty.edu ISBN-I3: 978-0-89236-83^-7 (pbk.) ISBN-IO: 0-89236-832-2 (pbk.) I. Lancret, Nicolas, 1690—1743- Dance before a fountain. 2- Lancret, Christopher Hudson, Publisher Nicolas, 1690 —1743"Criticism and interpretation. 3- Genre painting, Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief French — l8th century. I. Leonard, Mark, 1954 ~~ H- Lancret, Nicolas, 1690 — 1743. III. J. Paul Getty Museum. IV. Title. V. Series. Mollie Holtman, Series Editor ND553.L225A65 2006 Abby Sider, Manuscript Editor 759.4-dc22 Catherine Lorenz, Designer 2005012001 Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator Lou Meluso, Anthony Peres, Jack Ross, Photographers All photographs are copyrighted by the issuing institutions or by their Typesetting by Diane Franco owners, unless otherwise indicated. Figures 14, 16, 18, 29, 3^, 43> 57» 60, Printed in China by Imago 63 © Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, New York. Figures 21, 30, 31, 34, and 55 are use<i by kind permission of the Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London. Frontispiece: Michel Aubert (French, 1700 —1757)> Nicolas Lancret [detail], engraving, from Antoine Joseph Dezallier d'Argenville (French, 1680 — 1765), Abrege de la vie des plus fameux peintres (Paris, I745~52)> vol. -

The Mariology of St. Bonaventure As a Source of Inspiration in Italian Late Medieval Iconography

José María SALVADOR GONZÁLEZ, La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana The mariology of St. Bonaventure as a source of inspiration in Italian late medieval iconography La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana1 José María SALVADOR-GONZÁLEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 05/09/2014 Aceptado: 05/10/2014 Abstract: The central hypothesis of this paper raises the possibility that the mariology of St. Bonaventure maybe could have exercised substantial, direct influence on several of the most significant Marian iconographic themes in Italian art of the Late Middle Ages. After a brief biographical sketch to highlight the prominent position of this saint as a master of Scholasticism, as a prestigious writer, the highest authority of the Franciscan Order and accredited Doctor of the Church, the author of this paper presents the thesis developed by St. Bonaventure in each one of his many “Mariological Discourses” before analyzing a set of pictorial images representing various Marian iconographic themes in which we could detect the probable influence of bonaventurian mariology. Key words: Marian iconography; medieval art; mariology; Italian Trecento painting; St. Bonaventure; theology. Resumen: La hipótesis de trabajo del presente artículo plantea la posibilidad de que la doctrina mariológica de San Buenaventura haya ejercido notable influencia directa en varios de los más significativos temas iconográficos -

Insight: Contemplating the Cross of Christ in a Time of Healing

Insight: Contemplating the Cross of Christ in a time of healing September 12, 2018 WASHINGTON, D.C. – As a new school year begins we say ‘thank you’ to catechetical leaders and catechists who begin their ministry of faith formation, education, and witness to faith. As catechists renew their commitment to leading others to Jesus Christ, the one who stands at the heart of all catechetical efforts, they will hear the anguished voices of the faithful in these challenging times. One image of Jesus’ crucifixion offers a profound visual catechesis for catechists and those they serve who seek hope, wisdom, and perseverance in faith in a season of healing. An image for times of pain and scandal The Small Crucifixion was painted by Matthias Grünewald, the master German painter, in the early years of the 16th century, a time marked by widespread scandal and deep divisions in the Church, sadly not unlike our own today. Only two dozen works of the artist survive, among them The Small Crucifixion, from the permanent collection at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The painter’s best known masterpiece is the Isenheim Altarpiece, commissioned for the high altar of the church of the Monastery of Saint Anthony in Alsace, where patients suffering from the plague and various skin diseases were treated. In that large altarpiece, Grünewald depicts a crucified Christ whose body is racked with plague type scars. Patients bearing the pain of their physical afflictions found spiritual comfort as they gazed on the crucified Jesus and identified with the mystery of his unjust suffering. -

The Crucifixion C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Paolo Veneziano Venetian, active 1333 - 1358 The Crucifixion c. 1340/1345 tempera on panel painted surface: 31 x 38 cm (12 3/16 x 14 15/16 in.) overall: 33.85 x 41.1 cm (13 5/16 x 16 3/16 in.) framed: 37.2 x 45.4 x 5.7 cm (14 5/8 x 17 7/8 x 2 1/4 in.) Inscription: upper center: I.N.R.I. (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1939.1.143 ENTRY The Crucifixion is enacted in front of the crenellated wall of the city of Jerusalem. The cross is flanked above by four fluttering angels, three of whom collect the blood that flows from the wounds in Christ’s hands and side. To the left of the Cross, the Holy Women, a compact group, support the swooning Mary, mother of Jesus. Mary Magdalene kneels at the foot of the Cross, caressing Christ’s feet with her hands. To the right of the Cross stand Saint John the Evangelist, in profile, and a group of soldiers with the centurion in the middle, distinguished by a halo, who recognizes the Son of God in Jesus.[1] The painting’s small size, arched shape, and composition suggest that it originally belonged to a portable altarpiece, of which it formed the central panel’s upper tier [fig. 1].[2] The hypothesis was first advanced by Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà (originally drafted 1939, published 1969), who based it on stylistic, compositional, and iconographic affinities between a small triptych now in the Galleria Nazionale of Parma [fig. -

Tinabeattie Cta Paper Final

Paper given at the Annual Conference of the Catholic Theological Association of Great Britain 2006 Insight beyond sight: Sacramentality, Gender and the Eucharist with reference to the Isenheim Altarpiece 1 Tina Beattie Since Vatican II, the Eucharist has become riven by different interpretations, and gender has become an elusive but persistent theme that haunts the margins of our liturgical coherence. My concerns in this paper are with the relationship of the desiring and suffering body to the sacramental encounter between word and flesh in the unfolding drama of the Mass, and with the extent to which gender functions as a lens through which to view the mystery of Christ in the incarnation and the Eucharist. My argument is that both feminist and neo-orthodox theology 2 exaggerate the significance of gender and sexuality, and in so doing they make the sacramental life of the Church hostage to ideological struggles. I suggest that a more poetic and fluid understanding of gender might enable us to go beyond what many see as the rationalisation of worship after Vatican II, through the rekindling of a sense of mystery which resists the nostalgic mystique that infects much contemporary theology, not least through the cultic sex and death fantasies of Hans Urs von Balthasar. I have divided the paper into three parts, so that it is intended to form a reflective tryptich on the eucharist. In the first part, I consider some of the criticisms that have been made regarding the modern liturgy. In the second part, I contemplate the sacramental vision that informs Grünewald’s Isenheim altar. -

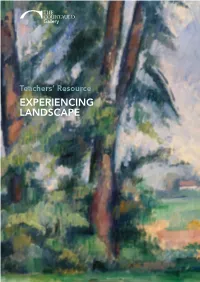

Experiencing Landscape Introduction

Teachers’ Resource EXPERIENCING LANDSCAPE INTRODUCTION The Courtauld Gallery’s world-renowned collections The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an extensive include Old Masters, Impressionist and Post- programme of learning activities for young people, Impressionist paintings, an outstanding prints and schools, colleges and teachers. From gallery tours and drawings collection and significant holdings of medieval, workshops to teachers’ events there are many ways for Renaissance and modern arts. The gallery is at the heart schools and students to engage with our collection, of the Courtauld institute of Art, a specialist college exhibitions and the Institute’s expertise. of the University of London and is housed in Somerset House. The Experiencing the Landscape resource is for teachers to learn about the history of Western Our teachers’ resources are based on The Courtauld’s Landscape painting looking at different historical art collection, exhibitions and displays. We are able to and social contexts across time. The resource is use the expertise of our students and scholars in our divided into chapters covering a range of themes. The learning resources to contribute to the understanding, accompanying CD can be used in class or shared with knowledge and enjoyment of art history. The your students and we hope the resource will help bring resources are intended as a way to share research and the subject of Landscape Art, and the artists’ experience understanding about art, architecture and art history. We of landscape, alive for you and your students. The hope that the articles and images will serve as a source resource ends with a glossary of art historical terms to of ideas and inspiration which can enrich lesson content aid your understanding.