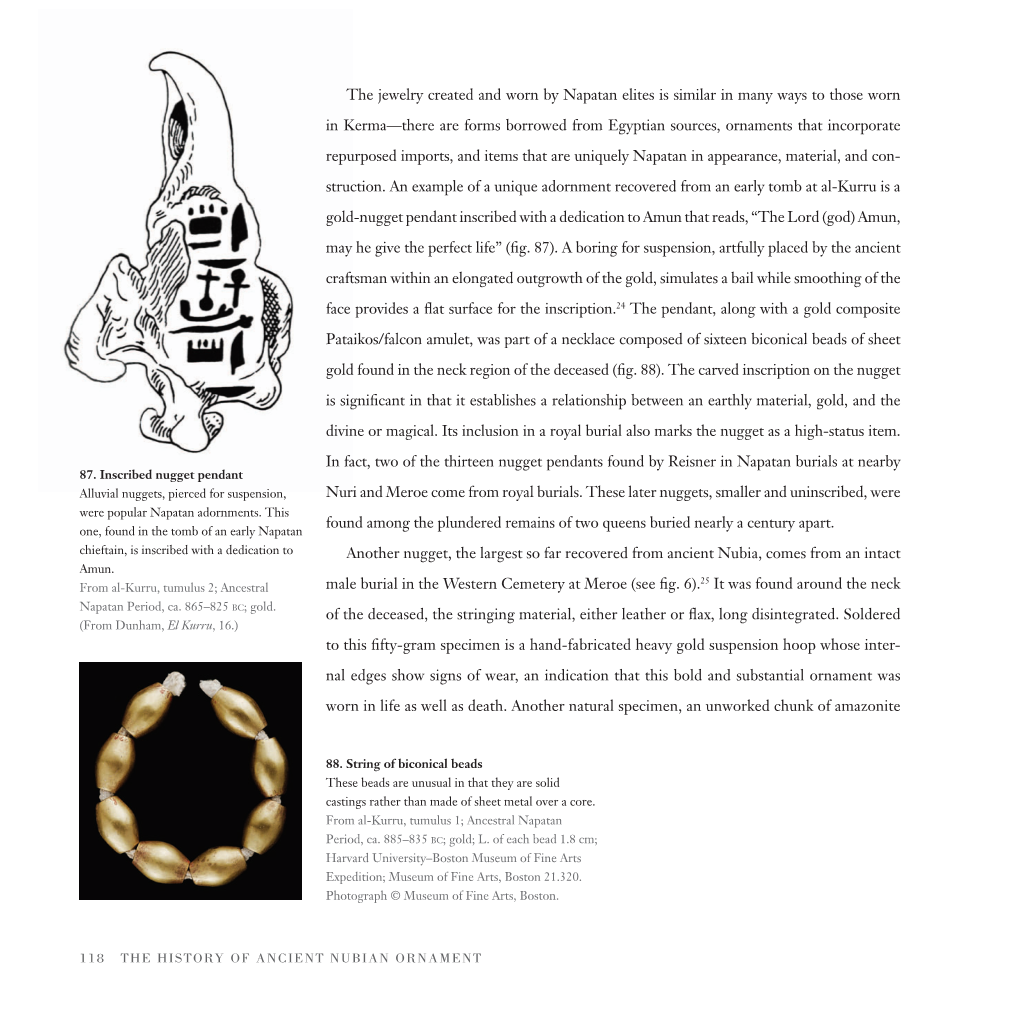

The Jewelry Created and Worn by Napatan Elites Is Similar in Many Ways to Those Worn in Kerma—There Are Forms Borrowed from Eg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Insights Into a Translucent Name Bead*

INSIGHTS INTO A TRANSLUCENT NAME BEAD* [PLANCHES XIII-XIV] BY PETER PAMMINGER Institut für Ägyptologie der Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität Saarstr. 21 (Campus) D-55099 MAINZ Recently, while visiting a private collection in Belgium, I became aware of a rock- crystal bead of quite distinctive qualities, which might once have belonged to the royal entourage of the 25th dynasty King Piye. The object was acquired not long ago on the art market, unfortunately without any proof of provenance. Its owner was kind enough to grant me permission to publish it. The bead itself (diameter 1.8 to 2.5 cm) has been drilled through (the hole 1.0 to 1.1 cm wide), embodying a sheet of gold in its core. One side of the surface being decorated with a raised cartouche bearing the inscription Mn-Ìpr-R{, the opposite side depicting a vulture1 who is carrying in each claw a symbol of {nÌ. Inbetween these two motives are situated two raised circular dots, each obviously representing a sun-disc (fig. + pl. XIII). * Abbreviations generally in accordance with Helck, W. und W. Westendorf (eds.), Lexikon der Ägyptologie (=LÄ), vol. VII, 1989, p. IX-XXXVIII. In addition: — RMT: Regio Museo di Torino. — Andrews, Jewellery I: C.A.R. Andrews, Jewellery I. From the Earliest Times to the Seventeenth Dynasty. Catalogue of Egyptian Antiquities in the British Museum VI, 1981. — Hall, Royal Scarabs: H.R.(H.) Hall, Catalogue of Egyptian Scarabs, etc., in the British Museum. Vol. I: Royal Scarabs, 1913. — Jaeger, OBO SA 2: B. Jaeger, Essai de classification et datation des scarabées Menkhéperrê (OBO SA 2), 1982. -

Kush Under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (C. 760-656 Bc)

CHAPTER FOUR KUSH UNDER THE TWENTY-FIFTH DYNASTY (C. 760-656 BC) "(And from that time on) the southerners have been sailing northwards, the northerners southwards, to the place where His Majesty is, with every good thing of South-land and every kind of provision of North-land." 1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence The names of Alara's (see Ch. 111.4.1) successor on the throne of the united kingdom of Kush, Kashta, and of Alara's and Kashta's descen dants (cf. Appendix) Piye,2 Shabaqo, Shebitqo, Taharqo,3 and Tan wetamani are recorded in Ancient History as kings of Egypt and the c. one century of their reign in Egypt is referred to as the period of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.4 While the political and cultural history of Kush 1 DS ofTanwetamani, lines 4lf. (c. 664 BC), FHNI No. 29, trans!. R.H. Pierce. 2 In earlier literature: Piankhy; occasionally: Py. For the reading of the Kushite name as Piye: Priese 1968 24f. The name written as Pyl: W. Spiegelberg: Aus der Geschichte vom Zauberer Ne-nefer-ke-Sokar, Demotischer Papyrus Berlin 13640. in: Studies Presented to F.Ll. Griffith. London 1932 I 71-180 (Ptolemaic). 3 In this book the writing of the names Shabaqo, Shebitqo, and Taharqo (instead of the conventional Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharka/Taharqa) follows the theoretical recon struction of the Kushite name forms, cf. Priese 1978. 4 The Dynasty may also be termed "Nubian", "Ethiopian", or "Kushite". O'Connor 1983 184; Kitchen 1986 Table 4 counts to the Dynasty the rulers from Alara to Tanwetamani. -

Antiguo Oriente

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Peftjauawybast, King of Nen-nesut: genealogy, art history, and the chronology of Late-Libyan Egypt AUTHORS Morkot, RG; James, PJ JOURNAL Antiguo Oriente DEPOSITED IN ORE 14 March 2017 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/26545 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication CUADERNOS DEL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE HISTORIA DEL ANTIGUO ORIENTE ANTIGUO ORIENTE Volumen 7 2009 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires - Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Departamento de Historia Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Av. Alicia Moreau de Justo 1500 P. B. Edificio San Alberto Magno (C1107AFD) Buenos Aires Argentina Sitio Web: www.uca.edu.ar/cehao Dirección electrónica: [email protected] Teléfono: (54-11) 4349-0200 int. 1189 Fax: (54-11) 4338-0791 Antiguo Oriente se encuentra indizada en: BiBIL, University of Lausanne, Suiza. DIALNET, Universidad de La Rioja, España. INIST, Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, Francia. LATINDEX, Catálogo, México. LIBRARY of CONGRESS, Washington DC, EE.UU. Núcleo Básico de Publicaciones Periódicas Científicas y Tecnológicas Argentinas (CONICET). RAMBI, Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalén, Israel. Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723 Impreso en la Argentina © 2010 UCA ISSN 1667-9202 AUTORIDADES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ARGENTINA Rector Monseñor Dr. -

Aegyptiannamesfemale.Pdf

Aahotep Fareeza Kesi Mukantagara OJufemi Sobkneferu Aat Fayrouz Khamaat Mukarramma Olabisi Sopdu Abana Femi Khamereernebty Muminah Olufemi Sotepenre Abar Fukayna Khamerernebty Mut Omorose Sponnesis Acenath Gehane Khasnebu Mutemhab Oni Sslama Adjedaa Gilukhepa Khedebneithireretbeneret Mutemwia Oseye Stateira Afshan Habibah Khenemet Mutemwiya Pakhet Subira Ahhotep Hafsah Khensa Mutneferu Panya Suma Ahhotpe Halima Khent Mutnefret Pasht Sutailja Ahmose- Meryetamun Hapu Khenteyetka Mutnodjme Pebatma Tabes Ahmose-Nefertiri Haqikah Khentkaues Mutnodjmet Peksater Tabesheribet Ahmose Hasina Khentkawes Muttuy Peshet Tabesheritbet Ahwere Hathor Khepri Muyet Phoenix Tabia Ain Hatnofer Khnemetamun Nabirye Pili Tabiry Ajalae Hatshepsut Khnumet Naeemah Pipuy Tabubu Akila Hebeny Khonsu Nailah Ptolema Taheret Alexandria Hehenhit Khutenptah Nait Ptolemais Tahirah Amanishakheto Hehet Kissa Nakht Qalhata Tahpenes Amenemopet Henetmire Kiya Nakhtsebastetru Qemanub Taimhotep Amenia Henhenet Koss Naneferher Quibilah Tairetdjeret Amenirdis Hentempet Kthyopia Nany Rabiah Tais Amenkhenwast Hentmira Lapis Nathifa Rai Taiuhery Amenti Henttawy Layla Naunakht Ramla Takhaaenbbastet Amessis Henttimehu Lotus Naunakhte Rashida Takharu Amosis Hentutwedjebu Maahorneferure Naunet Raziya Takhat Amunet Henut Maalana Nebefer Reddjedet Takheredeneset Amunnefret Henutdemit Maat Nebet Rehema Tale Anat Henutmehyt Maatkare Nebetawy Renenet Talibah Anhai Henutmire Maatneferure Nebethetepet Renenutet Tamin Anhay Henutnofret Maetkare Nebethut Reonet Tamutnefret Anippe Henutsen Mafuane -

Ancient Nubia and Kush IV

Ancient Nubia and Kush IV. The Kingdom of Kush The Nubians lived in Nubia SOUTH of Egypt; along the Nile, in present day SUDAN IV. The Kingdom of Kush Nubians did NOT rely on the Nile for their farming i. their land was fertile and receive rain all year long ii. grew crops like beans, YAMS, rice, and grains iii. herded longhorn cattle on savannas (grassy PLAINS) IV. The Kingdom of Kush A. The Nubians lived in the land of Nubia (later known as Kush) 2. Nubian villages combined to form the kingdom of Kerma a. wealthy via farming and mining of GOLD IV. The Kingdom of Kush B. The Kushite Kingdom escapes Egyptian rule 1. kingdom of KUSH starts ca 850BC w/ capital city of Napata a. Napata served as a trade link between central Africa and Egypt IV. The Kingdom of Kush 2. King KASHTA invades Egypt around 750BC a. his son King Piye completes conquest around 728BC 3. Kush builds temples & monuments similar to ones in Egypt a. small, steeply-sloped PYRAMIDS as tombs for their kings IV. The Kingdom of Kush 2. King KASHTA invades Egypt around 750BC a. his son King Piye completes conquest around 728BC 3. Kush builds temples & monuments similar to ones in Egypt a. small, steeply-sloped PYRAMIDS as tombs for their kings IV. The Kingdom of Kush 4. some Kushites followed customs from southern Africa such as ankle and ear jewelry 5. when ASSYRIANS conquer Egypt, Kushites head back south a. Kushites learn to use IRON for weapons & tools (like Assyrians) IV. -

Cipro Publication

CIPRO PUBLICATION 31 December 2009 Publication No. 201007 Notice No. 23 ( REGISTRATIONS ) Page : 1 : 201007 DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY NOTICE IN TERMS OF SECTION 26 (3) OF THE CLOSE CORPORATIONS ACT, 1984 (ACT 69 OF 1984) THAT THE NAMES OF THE CLOSE CORPORATIONS MENTIONED BELOW, HAVE BEEN STRUCK OFF THE REGISTER OF CLOSE CORPORATIONS AND THE REGISTRATION OF THEIR FOUNDING STATEMENTS HAVE BEEN CANCELLED WITH EFFECT FROM THE DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THIS NOTICE. R.J.MATHEKGA REGISTRAR OF CLOSE CORPORATIONS DEPARTEMENT VAN HANDEL EN NYWERHEID KENNISGEWING INGEVOLGE VAN ARTIKEL 26 (3) VAN DIE WET OP BESLOTE KORPORASIES, 1984 (WET 69 VAN 1984), DAT DIE NAME VAN DIE BESLOTE KORPORASIES HIERONDER GENOEM VAN DIE REGISTER VAN BESLOTE KORPORASIES GESKRAP IS EN REGISTRASIE VAN HUL STIGTINGSVERKLARINGS GEKANSELLEER IS MET INGANG VAN DIE DATUM VAN PUBLIKASIE VAN HIERDIE KENNISGEWING R.J.MATHEKGA REGISTRATEUR VAN BESLOTE KORPORASIES Page : 2 : 201007 Incorporation and Registration of Close Corporations • Inlywing en Registrasie van Beslote Korporasies ENTERPRISE No. ENTERPRISE NAME DATE B2009219170 A AND M BED AND BREAKFAST 01/12/2009 B2009219171 GUJA FUNERAL UNDERTAKERS 01/12/2009 B2009219172 MBENYANE CONSTRUCTION 01/12/2009 B2009219173 SIKHOSANA METAL WORK AND WELDING 01/12/2009 B2009219174 UYANDA PAVING SERVICES 01/12/2009 B2009219175 HOUSE OF WEARNERS 01/12/2009 B2009219176 FALATSA TRADING ENTERPRISE 01/12/2009 B2009219177 SHAALIAH FASHIONS 01/12/2009 B2009219178 SITHUNGA NGENYAMEKO GENERAL TRADING 01/12/2009 B2009219179 CUPID'S SPICE SHOP -

The History of Female Empowerment I: Regna

The History of Female Empowerment I: Regna December 7, 2019 Category: History Download as PDF One of the most significant neolithic societies of south-eastern Europe (in what would later be Dacia / Transnistria) is now known to archeologists as the Cucuteni-Trypillian civilization, which subsisted from the 6th to early 3rd millennium B.C. Their culture was overtly matriarchal; and their godhead was a female. The next major civilization (from c. 2600 B.C. to c. 1100 B.C.) was that of the Minoans, primarily located on Crete. That was also a predominantly matriarchal culture. The Minoans worshipped only goddesses (a precursor to Rhe[i]a–inspiration for the mythical princess, Ariadne). The enfranchisement of women goes back to the Bronze Age. Notable were the Sumerian “naditu”: women who owned and managed their own businesses. This is a reminder that mankind is a work-in- progress, making advancements in fits and starts. Such cultural saltations often occur pursuant to revolutionary movements; but sometimes civility is–as it were–baked into the cultural fabric by some serendipitous accident of history. To assay the empowerment of women across history and geography, let’s begin by surveying five ancient societies. Ancient Bharat[a] (India): Even as it was addled by the precedent of “varna” (a de facto caste system), the majority of women had a right to an education. Indeed, literacy was encouraged amongst both men and women; and it was even common for women to become “acharyas” (teachers). In the Cullavagga section of the “Vinaya Pitaka” (ref. the Pali Canon), Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) declared that women are every bit as capable of achieving enlightenment as are men. -

Dead-Reckoning the Start of the 22Nd Dynasty: from Shoshenq V Back to Shoshenq I

Dead-reckoning the Start of the 22nd Dynasty: from Shoshenq V back to Shoshenq I Robert Morkot and Peter James Kenneth Kitchen and other Egyptologists have claimed that a 10th-century BC date for Shoshenq I (founder of the 22nd Dynasty) can be arrived at not only from a philological identification with the biblical Shishak, but from chronological ‘dead- reckoning’ backwards through the Third Intermediate Period. One problem here is: where is the fixed point from which one begins retrocalculation? Kitchen himself counts backwards from his ‘Osorkon IV’, whom he identifies with the like-named king from the Piye Stela and the Shilkanni mentioned in Assyrian records in 716 BC. Yet there is no firm evidence that such an Osorkon ‘IV’ ever existed, while there is a mounting case for a return to the position of earlier Egyptologists that the king in question was the well-attested Osorkon III, presently dated to the first quarter of the 8th century BC. Equating him with the Osorkon of Piye would require lowering the dates of Osorkon III (and the last incumbents of the 22nd Dynasty) by some 40-50 years – a position strongly supported by archaeological, art-historical and genealogical evidence. Using these later dates, dead-reckoning backwards through the Dynasty (using the Pasenhor genealogy, Apis bull records and attested rather than imaginary reign lengths) brings us to a date for Shoshenq I in the second half of the 9th century. It would place him a century later than the biblical Shishak, making the equation of the two untenable. Another candidate needs to be sought for the biblical ‘king Shishak’. -

(B4) Chronology— Boundless Blessings Beyond Belief

Ralph Ellis Green Anne Ruth Rutledge Flora Marie Green The Tower of Babel by Hendrick van Cleve (Cleef) (III), 1500's CE THE WORD THAT CAME TO JEREMIAS concerning all the people of Juda in the fourth year of Joakim, son of Josias, king of Juda. [Editor's Note: There is no mention of Nebuchadnezzar the King of Babylon in the Greek Septuagint version of this scripture, at Jeremiah 25:1, and verses 28 to 30 of Chapter 52 of Jeremiah are non- existent. Rather than censorship, it may be seen as the later corruption of these scriptures, by the addition of material which they did not originally contain.] (English Translation of the Septuagint, originally published in 1851, by Sir Lancelot Charles Lee Brenton, Jeremiah 25:1, see also original ancient Greek text ) In Recognition of a Lifetime of Achievement by Phil Mickelson, born Jun 16, 1970. (Be Fore) (B4) Chronology— Boundless Blessings Beyond Belief Part 3: See also: <Part 2 of B4 Chronology <Part 1 of B4 Chronology Chapter 8: The Gift of Piankhi Alara Chapter 9: Man's Place in Time Chapter 10: Jerusalem Ancient Chronology's Key Chapter 11: Piye in the Sky Chapter 12: Conclusions (See also, previously: <Part 2 of B4 Chronology <Part 1 of B4 Chronology) from Babylonish and Scriptural History with the (unrelated) Best Ever Fixing Of Rome's Establishment and an independently determined New Egyptian/Ethiopian Ancient Timeline plus The Hushed UFO Story Too Lightly Exposed information about The Latest on Vitamin Excellence and much more... With love from Angelina Jolie Chapter 8: The Gift of Piankhi Alara [Robert Dean, quoting from a 1979 statement of Victor Marchetti, former executive assistant to the deputy director of the CIA]: We have indeed been contacted by extra-terrestrial beings, and the US government, in collusion with the other national powers of the earth, is determined to keep this information from the general public. -

Terminology and Chronology

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48208-0 — The Archaeology of Egypt in the Third Intermediate Period James Edward Bennett Excerpt More Information CHAPTER ONE TERMINOLOGY AND CHRONOLOGY he period 1078/6–664 bce is commonly known as the ‘Third TIntermediate Period’ (the Twenty-First to Twenty-Fifth Dynasty). The once unified government in the preceding Ramesside Period (Nineteenth to Twentieth Dynasty, 1295–1078/6 bce) was replaced by considerable political fragmentation in the Twenty-First Dynasty. The pharaohs now ruled from the north at Tanis, and a line of Theban High Priests of Amun (HPA) and army commanders controlled the south from Thebes. Alongside this shift of power was the re-emergence of local centres under the control of quasi-pharaohs and local Libyan, or warrior-class, chiefs, starting in the Twenty-Second Dynasty, and concurrently ruling from the mid-Twenty-Second Dynasty onwards. The warrior-chiefs were of the Meshwesh and Libu tribes that had gradually entered Egypt during the reigns of Ramesses II and Ramesses III as prisoners of war,1 and had subsequently been settled in the Delta and Middle Egypt.2 The demographic structure of Egypt also changed at this time as the incoming peoples integrated with the native Egyptian population. Egypt itself became a more politically inward-looking country, while its power hold over the Levant and Nubia was reduced.3 These factors had consequences for the structure of Egyptian society.4 This chapter begins by discussing how we have come to view relative chronological phases relating to the period after the New Kingdom, the origin of the term ‘Third Intermediate Period’, and the political and cultural climate in which the term was devised.