Public Parks and the Differentiation of Space in Leeds, 1850–1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map and Directions to DFC 2012 V1

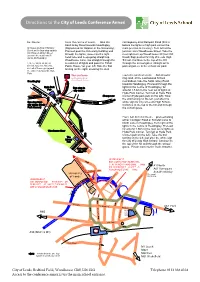

Directions to the City of Leeds Conference Annex Bus Routes From the centre of Leeds - Take the carriageway onto Rampart Road (this is A660 Otley Road towards Headingley, before the lights at high park corner the All buses go from Infirmary (Signposted for Skipton or the University). main junction is no entry). Turn left at the Street or the bus stop outside Proceed past the University building and junction onto Woodhouse Street. Take the Bar Risa on Albion Street through the lights, move into the right next right turn up Woodhouse cliff (not Cliff (across the road from St Johns McDonald's). hand lane and keep going straight up Road) Sign posted for City of Leeds High Woodhouse Lane. Go straight through the School. Continue to the top of the hill, 1,1b, 1c, 28,92, 93, 95, 96, second set of lights and pass the 'Firkin through the school gates, straight on to 97, 655, 729, 731, 755, 780, Public House' on your left. Take the first park anywhere in the school car park. x82 all of these go up past turning on the right, crossing the dual the university towards Hyde Park. We are here From the north of Leeds - A6120 outer on the same site as ring road, at the Lawnswood School City of Leeds School f Headingley f roundabout, take the A660, Otley Road i l C towards Headingley. Proceed through the e H Hyde Park s lights in the centre of Headingley, for ea u Bus stop to o di Pub C n h city centre around 1.5 km to the next set of lights at g l l i d e f y f L o Hyde Park Corner. -

Hyde Park Statistical Profile Vers 4 For

Enquiries and Manchester site: Real Life Methods Sociology A node of the ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Roscoe Building School of Social Sciences Manchester M13 9PL +44 (0)161 275 0265 [email protected] c.uk Leeds site: Leeds Social Sciences Institute Beech Grove House University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT +44 (0)113 343 7332 www.reallifemethods.ac.uk An Overview of Hyde Park / Burley Road, Leeds Andrew Clark April 2007 (Appendix 1 updated December 2007) A Work in Progress Contact: [email protected] 0113 343 7338 1 An Overview of Hyde Park / Burley Road, Leeds Introduction This document presents an overview of the Hyde Park / Burley Road area of Leeds. It consists of five sections: 1. An outline of the different ‘representational spaces’ the field site falls within. 2. A description of the economic and social geographies of the field site based on readily accessible public datasets. 3. Brief comments on some issues that may pose particular challenges to the area covered by the field site. 4. An Appendix listing ‘community’ orientated venues, facilities and voluntary organisations that operate within and close to the field site. 5. An overview of Dan Vickers’ Output area classification for northwest Leeds (included as Appendix). This document is updated regularly. Feedback, information on inaccuracies, or additional data is always appreciated. Please contact me at [email protected] , or at the Leeds Social Sciences Institute, The University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT. 2 About the Connected Lives Strand of the NCRM Real Life Methods Node This document provides a context for the Connected Lives strand of the Real Life Methods Node of the NCRM. -

Leeds City Council and B¡Ll Mckinnon

Statement of Gommon and Uncommon Ground between Leeds City Council and B¡ll McKinnon Reference -Green Space Background Paper (CDL/321 HMCA: lnner (and reference to l site in North) Ward: Hyde Park and Woodhouse (and L site in Chapel Allerton) Name of Representor: Bill McKinnon Representation number(s): PDEO2546 (Publication Draft stage) & PSE00599 (Pre Submission Change stage) Site Allocat¡ons Plan Examination Leeds Local Plan Leeds ffi CITY COUNCIL I 1 Introduction 1.1 This statement of common and uncommon ground has been prepared jointly between Leeds City Council and Bill McKinnon (the parties). 1.2 It sets out matters which Mr McKinnon and Leeds City Council agree on and also identifies specific issues raised by My McKinnon in his oral representation presented atthe Matter4: green space hearing session on24th October 2017 which the Council disagrees with. 2 Background 2.1 Mr McKinnon has expressed a number of concerns about the contents of the various versions of the Green Space Background Paper ln relation to green spacê identification in Hyde Park and Woodhouse Ward and the subsequent calculation of surpluses and deficiencies against the standards set out in Core Strategy Policy G3. He submitted representations at Publication Draft stage (PDE02546) and to the proposed pre-submission changes (PSE00599). The details contained in his representation to the Publication Draft SAP were considered carefully by the City Council and some changes were made (as identified at paragraph 3.1 below). Nevertheless, there remain facts and issues over which the parties disagree which are set out below in paragraph 4.1 3 Areas of Gommon Ground 3.1 The parties are in agreement in respect of the following: Statement Statement from Mr McKinnon Statement from Leeds City of Common Council Ground Number 1) Mr McKinnon promotes the designation The Council agrees with Mr and protection of the open space McKinnon and has proposed adjacent to the former sorting office off pre-submission change number Cliff Road as green space. -

Annual Meeting 2014

The Palaeontological Association 58th Annual Meeting 16th–19th December 2014 University of Leeds PROGRAMME abstracts and AGM papers Public transport to the University of Leeds BY TRAIN: FROM TRAIN STATION ON FOOT: Leeds Train Station links regularly to all major UK cities. You The University campus is a 20 minute walk from the train can get from the station to the campus on foot, by taxi or by station. The map below will help you find your way. bus. A taxi ride will take about 10 minutes and it will cost Leave the station through the exit facing the main concourse. approximately £5. Turn left past the bus stops and walk down towards City Square. Keeping City Square on your left, walk straight up FROM TRAIN STATION BY BUS: Park Row. At the top of the road turn right onto The Headrow, We advise you to take bus number 1 which departs from passing The Light shopping centre on your left. After The Light Infirmary Street. The bus runs approximately every 10 minutes turn left onto Woodhouse Lane to continue uphill. Keep going, and the journey takes 10 minutes. passing Morrisons, Leeds Metropolitan and the Dry Dock You should get off the bus just outside the Parkinson Building. boat pub heading for the large white clock tower. This is the (There is also the £1 Leeds City Bus which takes you from the Parkinson building. train station to the lower end of campus but the journey time is much longer). BY COACH: If you arrive by coach you can catch bus numbers 6,28 or 97 to the University (Parkinson Building). -

Leeds PSPO Consultation Overview 17Th July 2017

OFFICIAL - Sensitive Leeds PSPO Consultation Overview 17th July 2017 More about the ASB in this area could have Respondent Have you caused me to had a had a linked to the linked to with a noticed any Support for PSPO Area in a public within the last change where detrimental detrimental linked to use of household connection to ASB in this persistent unreasonable the PSPO space 12 months I went / what I effect on my effect on the alcohol misuse Psychoactive waste left on the area area? did quality of life quality of life Substances street of others Armley 128 97% 90% 87% 78% 73% 57% 59% 76% 84% - 25% 91% Burmantofts 22 91% 90% 85% 70% 50% 45% 60% 70% 65% - - 100% Farsley 25 64% 100% 88% 44% 50% 38% 44% 75% 69% - - 64% Garforth 43 72% 81% 74% 26% 35% 26% 29% 58% 45% - - 84% Gipton 20 90% 89% 94% 56% 50% 39% 28% 67% 67% - - 95% Guiseley 83 90% 93% 91% 65% 69% 47% 51% 72% 57% - - 93% Harehills 87 87% 80% 74% 64% 55% 43% 54% 68% 63% - 53% 83% Headingley 57 70% 83% 75% 55% 58% 45% 53% 63% 75% - - 67% Horsforth 45 64% 83% 79% 38% 45% 21% 14% 66% 45% - - 80% Killingbeck & Seacroft 89 63% 88% 82% 66% 64% 32% 41% 71% 43% - - 67% Kippax & Allerton Bywater 48 81% 87% 72% 41% 62% 18% 38% 59% 56% - - 92% Leeds City Centre 170 81% 83% 90% 58% 62% 43% 47% 77% 67% 45% - 74% Little Woodhouse 16 81% 100% 85% 77% 62% 38% 69% 85% 69% - - 75% Otley 65 52% 88% 82% 50% 68% 38% 35% 71% 71% - - 55% Pudsey 65 82% 94% 89% 51% 60% 36% 43% 75% 57% - - 91% Wetherby 28 82% 91% 96% 61% 83% 35% 39% 78% 74% - - 93% Woodhouse Moor and Little London 86 37% 81% 78% 63% 56% 31% 34% 69% 63% - - 22% Yeadon 40 88% 91% 89% 57% 71% 34% 46% 83% 69% - - 98% Total 1117 72% 87% 84% 60% 62% 40% 46% 72% 65% - - 76% Information for this report has been extracted from SNAP survey systems; absolute numbers may vary compared to other reports relating to data extracted at different dates. -

Aireborough Baseline Report B.Indd

Aireborough’s Natural and Built Environment Baseline Report October 2015 Image - Darren Sanderson Photography Limitations AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) has prepared this Report for the sole use Aireborough Neighbourhood Development Forum (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by AECOM. Where the conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others it is upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by AECOM has not been independently verifi ed by AECOM, unless otherwise stated in the Report. The methodology adopted and the sources of information used by AECOM in providing its services are outlined in this Report. The work described in this Report was undertaken in the period July 2015 to August 2015, although the evidence base goes wider, and is based on the conditions encountered and the information available during the said period of time. The scope of this Report and the services are accordingly factually limited by these circumstances. Where assessments of works or costs identifi ed in this Report are made, such assessments are based upon the information available at the time and where appropriate are subject to further investigations or information which may become available. AECOM disclaim any undertaking or obligation to advise any person of any change in any matter aff ecting the Report, which may come or be brought to AECOM’s attention after the date of the Report. -

History-Of-Headingley-RT2.Pdf

Headingley Development Trust Promoting Headingley A Headline History of Headingley Headingley Village The beginnings of Headingley village are lost in the mists of time. But its situation in a prime location suggests that it might be very ancient. The village is located on the higher, drier ridge between what would have been the less hospitable valleys of the River Aire to the west and Meanwood Beck to the east. And it is in a saddle on the ridge, providing ready access between the valleys. [An off-set cross-roads is still central to Headingley.] The Anglo-Saxon Era During the sixth century, the Angles arrived, settling in the north, giving England its name – and also naming the village. Among their number were Headda and his family, who founded, or perhaps occupied, the settlement on the hill, which became known as ‘Headda’s people’s place’ – or ‘Head-ing-ley’. Under Headda’s descendants, the village evidently flourished. [One field remains, on Headingley Hill, now used for grazing.] The Viking Era The Vikings colonised the north in the ninth century, and Jorvik Scir (York Shire) became one of the fourteen shires of the Danelaw. The Shire was divided into Ridings (thirdings), each in turn comprising wapentakes (where votes were taken by a show of weapons). The West Riding included Skyrack Wapentake, extending from the Wharfe to the Aire, and named after the Scir Ac (or Shire Oak) meeting place on the edge of Headingley village green. So, a millennium ago, Headingley was the number one settlement in Skyrack Wapentake. [The oak stood for another thousand years, finally collapsing in 1941.] The Norman Era The north did not take kindly to William of Normandy’s conquest in 1066, and rebellion broke out. -

Meanwood Valley Trail Is Essentially a Walking Route However Some Sections Are Either Public Or Permissive Bridleway

Introduction The MeanwoodValley has long been celebrated as a‘green artery’ in Leeds, bringing rural countryside into the heart of the city. This 7 mile linear walk takes you through some of the highlights of the cultural and natural history of the Valley. ACCESS TO THE TRAIL The number X84 bus is a regular bus service along the A660 and connects Woodhouse Moor and Golden Acre Park enabling the trail to be completed as a linear walk. For up to date times and information please look up www.wymetro.com or call (0113) 245 7676. WHO CAN USE THE TRAIL? The Meanwood Valley Trail is essentially a walking route however some sections are either public or permissive bridleway. These parts of the trail can also be used by horse riders and pedal cycles. For information on this or other rights of way issues please contact the Public Rights of Way team on 0113 395 7400. FURTHER INFORMATION The cultural and natural history of the Meanwood Valley is fascinatingly diverse.We can only give you a glimpse of it here. For more information please look up the Parks & Countryside Service on www.leeds.gov.uk or telephone (0113) 395 7400. We also advise that you reference the Meanwood Village Association who have published fantastic books on the history of the Valley (www.meanwoodvillage.org.uk). The publication of this leaflet has been sponsored by The Myrtle Tavern in Meanwood and local community group,The Meanwood Valley Partnership. A 7 mile walk from Woodhouse Moor We are grateful for their continued support of the Trail to Golden Acre Park and the Meanwood Valley. -

LEEDS CIVIC TRUST: HERITAGE at RISK 2018 URGENT (Immediate

LEEDS CIVIC TRUST: HERITAGE AT RISK 2018 URGENT (immediate structural danger) Locality Name Street Name, Postcode Owner Grade List Entry No. Comments Possible Future Use Aberford Deer Shelter Parlington Park, LS25 Prudential II 1300603 Surveyed in Autumn 2016 and in N/A very bad condition. Imminent collapse possible. Nov 18 – severe erosion and plant to save it is extremely urgent. City Centre Lambert’s Arcade (Yard) Briggate, LS1 EMCO / Vecktor No.2 is II 1375066 One of the buildings was used as a pop up Mixed Use, Retail. shop in late 2013 but reports of uPVC door and windows having been put in without permission. New application May 2014. City Centre Kirkgate Street 81 – 104 Kirkgate, LS2 Various Not listed n/a Part of the Kirkgate Townscape Heritage Mixed Use, Retail. Initiative. Oct 15 - No. 19 refurbishment complete. City Centre First White Cloth Hall 98 -101 Kirkgate, LS2 Rushbond (MSM) II* 1375042 Building works on site Sep 2018. Workshops, Retail, Mixed Use. Headingley Elinor Lupton Centre Headingley Lane, LS6 Wetherspoons II 1255938 Aug 17 – still empty and unused so now Public house. deemed vulnerable. July 17 – Approval given for COU to public house, but licence refused. Nov 18 – still empty. Holbeck Temple Mill and Gate Lodge Marshall Street, LS11 SJS Properties I 1375162 & 1375166 July 17 – Burberry has pulled out. Community, Arts, Event space, Museum. Hunslet Hunslet Mill and Victoria Goodman Street, LS10 JM Construction II* and II 1256253 & 1256251 July 17 – Recently sold to new developer and Residential. Works planning application in for apartments. Hunslet 16-18 Crown Point Road & Hunslet Road, LS10 Vastint II 1375260 & 1255569 Nov 15 – Carlsberg site sold to Vastint who Residential. -

Going Through the Ginnels Northbound

Going through the Ginnels Northbound If you’d like to explore historical Headingley, you can do no better than go through four of the neighbourhood’s longest ginnels (and two shorter ginnels), all following centuries-old rural pathways. The walk, of about two-and-a-half miles (or two miles with a shortcut), begins at Wrangthorn (Hyde Park Corner), follows old tracks which converged on Wood Mill (Tannery Park), and ends at Weetwood Hall. Starting the Walk All bus services southbound from Headingley Centre (except X84 and X85) will bring you to Hyde Park Corner, by Woodhouse Moor, where there are several cafes, to set you up before you begin the walk! [Access of course is curtailed during the coronavirus pandemic.] The settlement at the Corner originated as the hamlet of Wrangthorn (perhaps meaning ‘crooked hedge’), on the edge of Woodhouse Moor, where the lane from Leeds entered Headingley township. The name survives in the local Parish of Woodhouse & Wrangthorn, and in local streets. The name ‘Hyde Park Corner’, it seems, was proposed early in the 19th century, doubtless intended to capitalise on the rising reputation of the area. The name was generally adopted by the end of the century, by which time, villas and terraces had developed to the north, and brick terraces had proliferated to the south, with an inn, two churches and a school on the Corner. For more info, go to Historic Hyde Park. Ordnance Survey 1851 Leeds Public Rights Of Way Map Stage One, Headingley Hill Begin the walk from Hyde Park Corner down Woodhouse Street (to the right of the Hyde Park pub). -

Steer Davies Gleave's Socio-Economic Baseline Report

APPENDIX 8 Leeds Socio-Economic Baseline Report Report July 2009 Prepared for: Prepared by: Metro and Leeds City Council Steer Davies Gleave West Riding House 67 Albion Street Leeds LS1 5AA +44 (0)113 389 6400 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Contents Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 POPULATION 3 3 ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 7 Employment 7 Economic inactivity 8 4 DEPRIVATION 13 5 TRANSPORT CHARACTERISTICS 19 Transport Needs Index 21 FIGURES Figure 1.1 The City of Leeds within West Yorkshire 1 Figure 1.2 Leeds ward map - at the time of the 2001 Census 2 Figure 1.3 Leeds ward map – current (established 2004) 2 Figure 2.1 Population growth in the City of Leeds 3 Figure 2.2 West Yorkshire population densities 4 Figure 3.1 Locations of the largest employers in Leeds 8 Figure 3.2 Job Seeker Allowance Claimants 11 Figure 4.1 Index of Multiple Deprivation 13 Figure 4.2 Income deprivation 14 Figure 4.3 Employment deprivation 14 Figure 4.4 Health deprivation 15 Figure 4.5 Education deprivation 15 Figure 4.6 Housing deprivation 16 Figure 4.7 Living environment deprivation 16 Figure 4.8 Crime deprivation 17 Figure 5.1 Car ownership 20 Figure 5.2 Transport Needs Index in Leeds 22 TABLES Table 2-1 West Yorkshire Districts 3 Contents Table 2-2 Age of population 4 Table 2-3 Population aged 19 years old and under 5 Table 3-1 Jobs by industry 7 Table 3-2 Employment growth 8 Table 3-3 Economic inactivity 9 Table 3-4 Unemployment 10 Table 5-1 Car ownership 19 Table 5-2 % of households with no car or van 19 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 This report provides a description of the socio-economic characteristics of the City of Leeds. -

Hyde Park Far Headingley Headingley Weetwood West Park

Foxhills P Allotment Train Station Woodland Defibrillator Parking The Hollies Weetwood Playing Fields 44 W E E T W O O D Hollin Lane 50 Weetwood Lane Lawnswood School 49 Leeds City Academy FAR HEADINGLEY Woodhouse Ridge 38 Moor Road 19 37 Otley Road Bedford Fields 26 35 Far Headingley West Park Shops Local Centre 48 40 Shaw Lane Grove Lane Wood Lane North Hyde Park W E S T P A R K Cumberland Road Alma Road 43 45 27 Otley Road 34 Headingley Hill 25 Hyde Park Local Centre H E A D I N G L E Y 36 Woodhouse Lane 13 P 14 17 02 12 28 07 47 Headingley Lane P 09 P Spen Lane Headingley Town Centre 18 St Anne’s Road 22 Beckett's Park 31 16 01 42 06 23 Woodhouse Moor Butcher Hill Shops P Victoria Road Leeds Beckett University West Park Fields P 03 33 St Anne’s Road 11 North Lane 24 Brudenell Shops 32 Kirkstall Lane 39 Batcli e Wood Ash Road Area 46 15 H Y D E P A R K 30 Royal Park Backett Park Ash Road Emerald Headingley Stadium 41 Cardigan Road 08 Cardigan Triangle 21 20 Cardigan Road Shops 29 Burley Park Station The Turnways P Headingley Station P Y E L ING D A HE Friends in Headingley Live in Headingley Learn in Headingley Play in Headingley Explore in Headingley 01. HEART, Bennett Road Community Services Primary Schools Cinemas Hotels 02. Headingley Central, 01. HEART, Bennett Road 32. Brudenell Primary, Welton Place 39.