About the Research Historical Analysis There Are More Than 27,000 Parks and Green Spaces Across the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

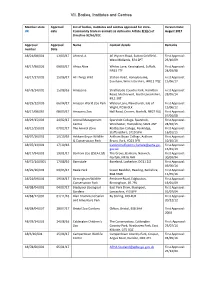

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

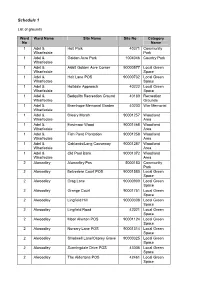

Parks Byelaws Attach 2 190808 , Item 72. PDF 438 KB

Schedule 1 List of grounds Ward Ward Name Site Name Site No Category No Name 1 Adel & Holt Park 40371 Community Wharfedale Park 1 Adel & Golden Acre Park 1004046 Country Park Wharfedale 1 Adel & A660 Golden Acre Corner 90000577 Local Green Wharfedale Space 1 Adel & Holt Lane POS 90000732 Local Green Wharfedale Space 1 Adel & Holtdale Approach 40222 Local Green Wharfedale Space 1 Adel & Bedquilts Recreation Ground 40189 Recreation Wharfedale Grounds 1 Adel & Bramhope Memorial Garden 40203 War Memorial Wharfedale 1 Adel & Breary Marsh 90001257 Woodland Wharfedale Area 1 Adel & Eastmoor Wood 90001468 Woodland Wharfedale Area 1 Adel & Fish Pond Plantation 90001258 Woodland Wharfedale Area 1 Adel & Oaklands/Long Causeway 90001287 Woodland Wharfedale Area 1 Adel & Old Pool Bank 90001372 Woodland Wharfedale Area 2 Alwoodley Alwoodley Pos 5000183 Community Park 2 Alwoodley Belvedere Court POS 90001580 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Crag Lane 90000909 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Grange Court 90001751 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Lingfield Hill 90000308 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Lingfield Road 42021 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Moor Allerton POS 90001124 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Nursery Lane POS 90001314 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Shadwell Lane/Osprey Grove 90000325 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Sunningdale Drive POS 43006 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley The Aldertons POS 42461 Local Green Space Ward Ward Name Site Name Site No Category No Name 2 Alwoodley Turnberry Estate POS 44017 Local Green Space 2 Alwoodley Wigton Chase POS 90000530 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Roundhay Park to Temple Newsam

Hill Top Farm Kilometres Stage 1: Roundhay Park toNorth Temple Hills Wood Newsam 0 Red Hall Wood 0.5 1 1.5 2 0 Miles 0.5 1 Ram A6120 (The Wykebeck Way) Wood Castle Wood Great Heads Wood Roundhay start Enjoy the Slow Tour Key The Arboretum Lawn on the National Cycle Roundhay Wellington Hill Park The Network! A58 Take a Break! Lakeside 1 Braim Wood The Slow Tour of Yorkshire is inspired 1 Lakeside Café at Roundhay Park 1 by the Grand Depart of the Tour de France in Yorkshire in 2014. Monkswood 2 Cafés at Killingbeck retail park Waterloo Funded by the Public Health Team A6120 Military Lake Field 3 Café and ice cream shop in Leeds City Council, the Slow Tour at Temple Newsam aims to increase accessible cycling opportunities across the Limeregion Pits Wood on Gledhow Sustrans’ National Cycle Network. The Network is more than 14,000 Wykebeck Woods miles of traffic-free paths, quiet lanesRamshead Wood and on-road walking and cycling A64 8 routes across the UK. 5 A 2 This route is part of National Route 677, so just follow the signs! Oakwood Beechwood A 6 1 2 0 A58 Sustrans PortraitHarehills Bench Fearnville Brooklands Corner B 6 1 5 9 A58 Things to see and do The Green Recreation Roundhay Park Ground Parklands Entrance to Killingbeck Fields 700 acres of parkland, lakes, woodland and activityGipton areas, including BMX/ Tennis courts, bowling greens, sports pitches, skateboard ramps, Skate Park children’s play areas, fishing, a golf course and a café. www.roundhaypark.org.uk Kilingbeck Bike Hire A6120 Tropical World at Roundhay Park Fields Enjoy tropical birds, butterflies, iguanas, monkeys and fruit bats in GetThe Cycling Oval can the rainforest environment of Tropical World. -

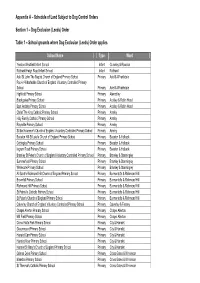

Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1

Appendix A – Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1 – Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order Table 1 – School grounds where Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order applies School Name Type Ward Yeadon Westfield Infant School Infant Guiseley & Rawdon Rothwell Haigh Road Infant School Infant Rothwell Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Pool-in-Wharfedale Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Highfield Primary School Primary Alwoodley Blackgates Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood East Ardsley Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood Christ The King Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Holy Family Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Raynville Primary School Primary Armley St Bartholomew's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Armley Beeston Hill St Luke's Church of England Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Cottingley Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Ingram Road Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Bramley St Peter's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Summerfield Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Whitecote Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Brownhill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Richmond Hill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill St Patrick's Catholic Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill -

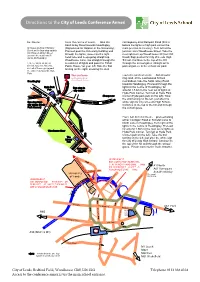

Map and Directions to DFC 2012 V1

Directions to the City of Leeds Conference Annex Bus Routes From the centre of Leeds - Take the carriageway onto Rampart Road (this is A660 Otley Road towards Headingley, before the lights at high park corner the All buses go from Infirmary (Signposted for Skipton or the University). main junction is no entry). Turn left at the Street or the bus stop outside Proceed past the University building and junction onto Woodhouse Street. Take the Bar Risa on Albion Street through the lights, move into the right next right turn up Woodhouse cliff (not Cliff (across the road from St Johns McDonald's). hand lane and keep going straight up Road) Sign posted for City of Leeds High Woodhouse Lane. Go straight through the School. Continue to the top of the hill, 1,1b, 1c, 28,92, 93, 95, 96, second set of lights and pass the 'Firkin through the school gates, straight on to 97, 655, 729, 731, 755, 780, Public House' on your left. Take the first park anywhere in the school car park. x82 all of these go up past turning on the right, crossing the dual the university towards Hyde Park. We are here From the north of Leeds - A6120 outer on the same site as ring road, at the Lawnswood School City of Leeds School f Headingley f roundabout, take the A660, Otley Road i l C towards Headingley. Proceed through the e H Hyde Park s lights in the centre of Headingley, for ea u Bus stop to o di Pub C n h city centre around 1.5 km to the next set of lights at g l l i d e f y f L o Hyde Park Corner. -

THE LIFE and FAMILY of THOMAS NICHOLSON of ROUNDHAY PARK" © by Neville Hurworth

From Oak Leaves, Part 1, Spring 2001 - published by Oakwood and District Historical Society [ODHS] "THE LIFE AND FAMILY OF THOMAS NICHOLSON OF ROUNDHAY PARK" © by Neville Hurworth Many thousands of visitors come to Roundhay Park each year to attend the several major events hosted annually by Leeds City Council such as music festivals and the November bonfire and fireworks display, or to enjoy the delights of the Tropical World and Canal Gardens. Others are simply content to stroll through the trees and round the Lakes, or to sit and admire the view in such pleasant surroundings as the Park offers in full measure all the year round. Some of these visitors may know that the Park was for many years part of the Roundhay estate of the Nicholson family. I suspect that very few of them though, will have heard of Thomas Nicholson (1764 -1821), who in the early 19th century, acquired this estate and created the main features of Roundhay Park as we know it today. Thomas Nicholson was a Quaker, born into a comfortable but none too wealthy clothier's family in Chapel Allerton. Although he died in Roundhay, he left Chapel Allerton in his early adult years for London where he married and lived for most of his life. Somehow, he found the means to set up as an insurance broker and merchant and acquired great wealth. In 1799 he bought an estate in Chapel Allerton which included Chapel Allerton Hall, and in 1803, along with another Quaker, Samuel Elam, he purchased the Roundhay Estate from Lord Stourton. -

Athlete Guide

CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES ATHLETE GUIDE SUNDAY 6 JUNE 2021 CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES - ATHLETE GUIDE 01 WELCOME WELCOME FROM AJ BELL WORLD TRIATHLON LEEDS 2021 Welcome to the AJ Bell 2021 World Triathlon Leeds. Following last year’s postponement, we’re really excited for you to join us in Roundhay Park for this festival of triathlon where a packed weekend will see the park transformed into a hub of triathlon. As an organising team, we’ve worked hard to ensure that the event is Covid-Secure, so that you can take part knowing you’re in safe hands whilst having the same great experience. The brand-new courses and entire event process have been designed to give you the physical challenge WAYNE COYLE you’re after in an environment that participants, volunteers and staff can feel comfortable in. Event Director, There have been so many people from British Triathlon, Leeds City Council, AJ Bell 2021 World World Triathlon and UK Sport involved in helping to make this year’s event Triathlon Leeds possible, and there will be even more volunteers and officials involved across the weekend to support you. My sincere thanks go out to everyone involved in what will be an event like no other. I hope you have a great race and enjoy the Roundhay Park experience. WELCOME FROM BRITISH TRIATHLON AJ Bell 2021 World Triathlon Leeds is Britain’s flagship triathlon event and I’m delighted to welcome you as you join us for our fifth year in the city. Covid-19 has meant many of you will have had few or no swim, bike, run events to take part in for the past year or so, which is why it’s so exciting for me that we’re able to host this year’s event to help bring the sport together again. -

Public Parks and the Differentiation of Space in Leeds, 1850–1914

Urban History (2021), 48, 552–571 doi:10.1017/S0963926820000449 RESEARCH ARTICLE Spaces apart: public parks and the differentiation of space in Leeds, 1850–1914 Nathan Booth1, David Churchill2* , Anna Barker3 and Adam Crawford4† 1Independent Scholar 2Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT 3Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT 4Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract While the Victorian ideal of the public park is well understood, we know less of how local governors sought to realize this ideal in practice. This article is concerned with park-making as a process – contingent, unstable, open – rather than with parks as outcomes – determined, settled, closed. It details how local governors bounded, designed and regulated park spaces to differentiate them as ‘spaces apart’ within the city, and how this programme of spatial governance was obstructed, frustrated and diverted by political, environmental and social forces. The article also uses this historical analysis to provide a new perspective on the future prospects of urban parks today. Introduction How might an urban historian approach the Victorian municipal park? It was both an ideal space – a jewel in the civilized and harmonious city of the future – and an actual space in which people met, played, rowed and rallied.1 This immediately sug- gests two broad modes of investigation: first, a cultural history of how the park was represented, and how it imaginatively constituted collective identities and attach- ments; second, a social history of how the park was experienced in everyday life, and how it functioned as a crucible of wider social relations. -

Hyde Park Statistical Profile Vers 4 For

Enquiries and Manchester site: Real Life Methods Sociology A node of the ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Roscoe Building School of Social Sciences Manchester M13 9PL +44 (0)161 275 0265 [email protected] c.uk Leeds site: Leeds Social Sciences Institute Beech Grove House University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT +44 (0)113 343 7332 www.reallifemethods.ac.uk An Overview of Hyde Park / Burley Road, Leeds Andrew Clark April 2007 (Appendix 1 updated December 2007) A Work in Progress Contact: [email protected] 0113 343 7338 1 An Overview of Hyde Park / Burley Road, Leeds Introduction This document presents an overview of the Hyde Park / Burley Road area of Leeds. It consists of five sections: 1. An outline of the different ‘representational spaces’ the field site falls within. 2. A description of the economic and social geographies of the field site based on readily accessible public datasets. 3. Brief comments on some issues that may pose particular challenges to the area covered by the field site. 4. An Appendix listing ‘community’ orientated venues, facilities and voluntary organisations that operate within and close to the field site. 5. An overview of Dan Vickers’ Output area classification for northwest Leeds (included as Appendix). This document is updated regularly. Feedback, information on inaccuracies, or additional data is always appreciated. Please contact me at [email protected] , or at the Leeds Social Sciences Institute, The University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT. 2 About the Connected Lives Strand of the NCRM Real Life Methods Node This document provides a context for the Connected Lives strand of the Real Life Methods Node of the NCRM. -

De Classic Album Collection

DE CLASSIC ALBUM COLLECTION EDITIE 2013 Album 1 U2 ‐ The Joshua Tree 2 Michael Jackson ‐ Thriller 3 Dire Straits ‐ Brothers in arms 4 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born in the USA 5 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Rumours 6 Bryan Adams ‐ Reckless 7 Pink Floyd ‐ Dark side of the moon 8 Eagles ‐ Hotel California 9 Adele ‐ 21 10 Beatles ‐ Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band 11 Prince ‐ Purple Rain 12 Paul Simon ‐ Graceland 13 Meat Loaf ‐ Bat out of hell 14 Coldplay ‐ A rush of blood to the head 15 U2 ‐ The unforgetable Fire 16 Queen ‐ A night at the opera 17 Madonna ‐ Like a prayer 18 Simple Minds ‐ New gold dream (81‐82‐83‐84) 19 Pink Floyd ‐ The wall 20 R.E.M. ‐ Automatic for the people 21 Rolling Stones ‐ Beggar's Banquet 22 Michael Jackson ‐ Bad 23 Police ‐ Outlandos d'Amour 24 Tina Turner ‐ Private dancer 25 Beatles ‐ Beatles (White album) 26 David Bowie ‐ Let's dance 27 Simply Red ‐ Picture Book 28 Nirvana ‐ Nevermind 29 Simon & Garfunkel ‐ Bridge over troubled water 30 Beach Boys ‐ Pet Sounds 31 George Michael ‐ Faith 32 Phil Collins ‐ Face Value 33 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born to run 34 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Tango in the night 35 Prince ‐ Sign O'the times 36 Lou Reed ‐ Transformer 37 Simple Minds ‐ Once upon a time 38 U2 ‐ Achtung baby 39 Doors ‐ Doors 40 Clouseau ‐ Oker 41 Bruce Springsteen ‐ The River 42 Queen ‐ News of the world 43 Sting ‐ Nothing like the sun 44 Guns N Roses ‐ Appetite for destruction 45 David Bowie ‐ Heroes 46 Eurythmics ‐ Sweet dreams 47 Oasis ‐ What's the story morning glory 48 Dire Straits ‐ Love over gold 49 Stevie Wonder ‐ Songs in the key of life 50 Roxy Music ‐ Avalon 51 Lionel Richie ‐ Can't Slow Down 52 Supertramp ‐ Breakfast in America 53 Talking Heads ‐ Stop making sense (live) 54 Amy Winehouse ‐ Back to black 55 John Lennon ‐ Imagine 56 Whitney Houston ‐ Whitney 57 Elton John ‐ Goodbye Yellow Brick Road 58 Bon Jovi ‐ Slippery when wet 59 Neil Young ‐ Harvest 60 R.E.M. -

Leeds City Council and B¡Ll Mckinnon

Statement of Gommon and Uncommon Ground between Leeds City Council and B¡ll McKinnon Reference -Green Space Background Paper (CDL/321 HMCA: lnner (and reference to l site in North) Ward: Hyde Park and Woodhouse (and L site in Chapel Allerton) Name of Representor: Bill McKinnon Representation number(s): PDEO2546 (Publication Draft stage) & PSE00599 (Pre Submission Change stage) Site Allocat¡ons Plan Examination Leeds Local Plan Leeds ffi CITY COUNCIL I 1 Introduction 1.1 This statement of common and uncommon ground has been prepared jointly between Leeds City Council and Bill McKinnon (the parties). 1.2 It sets out matters which Mr McKinnon and Leeds City Council agree on and also identifies specific issues raised by My McKinnon in his oral representation presented atthe Matter4: green space hearing session on24th October 2017 which the Council disagrees with. 2 Background 2.1 Mr McKinnon has expressed a number of concerns about the contents of the various versions of the Green Space Background Paper ln relation to green spacê identification in Hyde Park and Woodhouse Ward and the subsequent calculation of surpluses and deficiencies against the standards set out in Core Strategy Policy G3. He submitted representations at Publication Draft stage (PDE02546) and to the proposed pre-submission changes (PSE00599). The details contained in his representation to the Publication Draft SAP were considered carefully by the City Council and some changes were made (as identified at paragraph 3.1 below). Nevertheless, there remain facts and issues over which the parties disagree which are set out below in paragraph 4.1 3 Areas of Gommon Ground 3.1 The parties are in agreement in respect of the following: Statement Statement from Mr McKinnon Statement from Leeds City of Common Council Ground Number 1) Mr McKinnon promotes the designation The Council agrees with Mr and protection of the open space McKinnon and has proposed adjacent to the former sorting office off pre-submission change number Cliff Road as green space.