History-Of-Headingley-RT2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notices and Proceedings for the North East of England 2454

Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Notices and Proceedings Publication Number: 2454 Publication Date: 18/12/2020 Objection Deadline Date: 08/01/2021 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 18/12/2020 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. -

Health Profile Overview for Garforth and Swillington Ward

Garforth and Swillington Ward Health profile overview for Garforth and Swillington ward Population: 21,325 Garforth and Swillington ward has a GP registered Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. population of 21,325 making it the fifth smallest ward Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the second least deprived fifth of Leeds. In 100-104 Males: 10,389 Females: 10,936 Leeds terms the ward is ranked sixth least by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is very different to Leeds, 60-64 but with many more elderly and far adults and children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Garforth and Swillington 30-34 ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 63% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child 37% obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is used in these cases. -

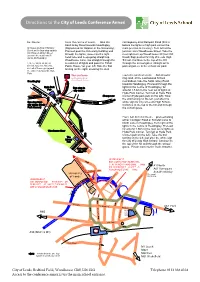

Map and Directions to DFC 2012 V1

Directions to the City of Leeds Conference Annex Bus Routes From the centre of Leeds - Take the carriageway onto Rampart Road (this is A660 Otley Road towards Headingley, before the lights at high park corner the All buses go from Infirmary (Signposted for Skipton or the University). main junction is no entry). Turn left at the Street or the bus stop outside Proceed past the University building and junction onto Woodhouse Street. Take the Bar Risa on Albion Street through the lights, move into the right next right turn up Woodhouse cliff (not Cliff (across the road from St Johns McDonald's). hand lane and keep going straight up Road) Sign posted for City of Leeds High Woodhouse Lane. Go straight through the School. Continue to the top of the hill, 1,1b, 1c, 28,92, 93, 95, 96, second set of lights and pass the 'Firkin through the school gates, straight on to 97, 655, 729, 731, 755, 780, Public House' on your left. Take the first park anywhere in the school car park. x82 all of these go up past turning on the right, crossing the dual the university towards Hyde Park. We are here From the north of Leeds - A6120 outer on the same site as ring road, at the Lawnswood School City of Leeds School f Headingley f roundabout, take the A660, Otley Road i l C towards Headingley. Proceed through the e H Hyde Park s lights in the centre of Headingley, for ea u Bus stop to o di Pub C n h city centre around 1.5 km to the next set of lights at g l l i d e f y f L o Hyde Park Corner. -

Health Profile Overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward

Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward Health profile overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward Population: 30,290 Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward has a GP Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. registered population of 30,290 making it the fifth Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th largest ward in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the most deprived fifth of Leeds. 100-104 Males: 15,829 Females: 14,458 In Leeds terms the ward is ranked second by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is similar to Leeds, but 60-64 with fewer elderly and many more children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Burmantofts and Richmond 30-34 Hill ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 81% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is 19% used in these cases. -

56 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

56 bus time schedule & line map 56 Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre View In Website Mode The 56 bus line (Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre: 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM (2) Moor Grange <-> Whinmoor: 5:15 AM - 10:40 PM (3) Swarcliffe <-> Moor Grange: 5:07 AM (4) Whinmoor <-> Leeds City Centre: 11:10 PM - 11:40 PM (5) Whinmoor <-> Moor Grange: 5:15 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 56 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 56 bus arriving. Direction: Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre 56 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Latchmere Drive, Moor Grange Latchmere Green, Leeds Tuesday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Latchmere Road, Moor Grange Wednesday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Old Farm Approach, Moor Grange Thursday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Friday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Old Oak Drive, West Park Old Oak Garth, Leeds Saturday 11:10 PM Beckett Park, West Park Ghyll Road, West Park 56 bus Info Woodbridge Crescent, Beckett Park Direction: Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre Stops: 26 Woodbridge Place, Beckett Park Trip Duration: 22 min Queenswood Drive, Leeds Line Summary: Latchmere Drive, Moor Grange, Latchmere Road, Moor Grange, Old Farm Approach, Queenswood Road, Beckett Park Moor Grange, Old Oak Drive, West Park, Beckett Jaques Close, Leeds Park, West Park, Ghyll Road, West Park, Woodbridge Crescent, Beckett Park, Woodbridge Place, Beckett Eden -

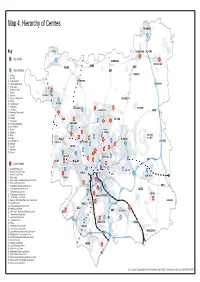

Map 4. Hierarchy of Centres WETHERBY

Map 4. Hierarchy of Centres WETHERBY 27 Key OTLEY COLLINGHAM A1 (M) 9 City Centre 4 22 HAREWOOD BOSTON SPA A659 A660 A58 Town Centres A61 1 Armley BARDSEY 2 Bramley 3 Chapel Allerton BRAMHOPE 4 Colton (Selby Road) BRAMHAM 5 Cross Gates 6 Dewsbury Road 12 7 Farsley 9 8 Garforth GUISELEY 9 Guiseley, Otley Road 28 SCARCROFT 10 Halton 11 Harehills Lane YEADON 12 Headingley COOKRIDGE 1 29 THORNER 13 Holt Park 13 ALWOODLEY A64 14 Horsforth, Town Street 27 15 Hunslet 16 Kirkstall A65A6A65 18 A6120A6A61661201212020 17 Meanwood 19 26 3311 18 Middleton Ring Road HORSFORTHHORSFOS RTHRTTHTH 19 Moor Allerton 141 20 Morley CHAPELCHAC PEL 21 Oakwood 6 AALLALLERTONERTRTR ONN 17 BARWICKBARARW 22 Otley 3 23 Pudsey 14 3333 1177 IN ELMETELM A657A6577 25 SEACROFTSEASE CRROR FTT 24 Richmond Hill 221 A1 (M) CALVERLEYCACALC VERRLEYY HEADINGLEYHHEAHEADIND GLLEY 25 Rothwell 1212 16 26 RODLEYRODR LEYY 26 Seacroft 133 8 27 Wetherby 1166 1199 28 Yeadon 7 2 28 FARSLEYFARARSLSLES Y HAREHILLSHAREHILLS 11 5 2121 5 M1 A647A6477 300 BRAMLEYBRABBRRARAMMLEY Local Centres 22 24 1 Alwoodley King Lane 23 1 CITYY 10 2 Beeston Hill Local Centre HALTONHALTON 8 7 ARMLEY CENTRECCENENTRTRETR 4 3 Beeston Local Centre GARFORTH 4 Boston Spa PUDSEY 5 Burley Lodge (Woodsley Road) Local Centre 15 6 Butcher Hill Local Centre 23 7 Chapeltown (Pudsey) Local Centre A63 2 15 8 Chapeltown Road Local Centre 6 A642 9 Collingham Local Centre 10 Drighlington Local Centre 3 KIPPAX BEESTON M621 11 East Ardsley Local Centre 20 12 Guiseley Oxford Road/Town Gate Town Centre 32 LEDSHAM 13 Harehills Corner -

Public Parks and the Differentiation of Space in Leeds, 1850–1914

Urban History (2021), 48, 552–571 doi:10.1017/S0963926820000449 RESEARCH ARTICLE Spaces apart: public parks and the differentiation of space in Leeds, 1850–1914 Nathan Booth1, David Churchill2* , Anna Barker3 and Adam Crawford4† 1Independent Scholar 2Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT 3Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT 4Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract While the Victorian ideal of the public park is well understood, we know less of how local governors sought to realize this ideal in practice. This article is concerned with park-making as a process – contingent, unstable, open – rather than with parks as outcomes – determined, settled, closed. It details how local governors bounded, designed and regulated park spaces to differentiate them as ‘spaces apart’ within the city, and how this programme of spatial governance was obstructed, frustrated and diverted by political, environmental and social forces. The article also uses this historical analysis to provide a new perspective on the future prospects of urban parks today. Introduction How might an urban historian approach the Victorian municipal park? It was both an ideal space – a jewel in the civilized and harmonious city of the future – and an actual space in which people met, played, rowed and rallied.1 This immediately sug- gests two broad modes of investigation: first, a cultural history of how the park was represented, and how it imaginatively constituted collective identities and attach- ments; second, a social history of how the park was experienced in everyday life, and how it functioned as a crucible of wider social relations. -

Hyde Park Statistical Profile Vers 4 For

Enquiries and Manchester site: Real Life Methods Sociology A node of the ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Roscoe Building School of Social Sciences Manchester M13 9PL +44 (0)161 275 0265 [email protected] c.uk Leeds site: Leeds Social Sciences Institute Beech Grove House University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT +44 (0)113 343 7332 www.reallifemethods.ac.uk An Overview of Hyde Park / Burley Road, Leeds Andrew Clark April 2007 (Appendix 1 updated December 2007) A Work in Progress Contact: [email protected] 0113 343 7338 1 An Overview of Hyde Park / Burley Road, Leeds Introduction This document presents an overview of the Hyde Park / Burley Road area of Leeds. It consists of five sections: 1. An outline of the different ‘representational spaces’ the field site falls within. 2. A description of the economic and social geographies of the field site based on readily accessible public datasets. 3. Brief comments on some issues that may pose particular challenges to the area covered by the field site. 4. An Appendix listing ‘community’ orientated venues, facilities and voluntary organisations that operate within and close to the field site. 5. An overview of Dan Vickers’ Output area classification for northwest Leeds (included as Appendix). This document is updated regularly. Feedback, information on inaccuracies, or additional data is always appreciated. Please contact me at [email protected] , or at the Leeds Social Sciences Institute, The University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT. 2 About the Connected Lives Strand of the NCRM Real Life Methods Node This document provides a context for the Connected Lives strand of the Real Life Methods Node of the NCRM. -

Blue Plaques Erected Since the Publication of This Book

Leeds Civic Trust Blue Plaques No Title Location Unveiler Date Sponsor 1 Burley Bar Stone Inside main entrance of Leeds Lord Marshall of Leeds, President of Leeds Civic 27 Nov ‘87 Leeds & Holbeck Building Society Building Society, The Headrow Trust, former Leader of Leeds City Council Leeds 1 2 Louis Le Prince British Waterways, Leeds Mr. William Le Prince Huettle, great-grandson 13 Oct ‘88 British Waterways Board Bridge, Lower Briggate, Leeds of Louis Le Prince (1st Plaque) 1 3 Louis Le Prince BBC Studios, Woodhouse Sir Richard Attenborough, Actor, Broadcaster 14 Oct ‘88 British Broadcasting Corporation Lane, Leeds 2 and Film Director (2nd Plaque) 4 Temple Mill Marshall Street, Leeds 11 Mr Bruce Taylor, Managing Director of Kay’s 14 Feb ‘89 Kay & Company Ltd 5 18 Park Place 18 Park Place, Leeds 1 Sir Christopher Benson, Chairman, MEPC plc 24 Feb ‘89 MEPC plc 6 The Victoria Hotel Great George Street, Leeds 1 Mr John Power MBE, Deputy Lord Lieutenant of 25 Apr ‘89 Joshua Tetley & Sons Ltd West Yorkshire 7 The Assembly Rooms Crown Street, Leeds 2 Mr Bettison (Senior) 27 Apr ‘89 Mr Bruce Bettison, then Owner of Waterloo Antiques 8 Kemplay’s Academy Nash’s Tudor Fish Restaurant, Mr. Lawrence Bellhouse, Proprietor, Nash’s May ‘89 Lawrence Bellhouse, Proprietor, Nash’s off New Briggate, Leeds 1 Tudor Fish Restaurant Tudor Fish Restaurant 9 Brodrick’s Buildings Cookridge Street, Leeds 2 Mr John M. Quinlan, Director, Trinity Services 20 Jul ‘89 Trinity Services (Developers) 10 The West Bar Bond Street Centre, Boar Councillor J.L. Carter, Lord Mayor of Leeds 19 Sept ‘89 Bond Street Shopping Centre Merchants’ Lane, Leeds 1 Association Page 1 of 14 No Title Location Unveiler Date Sponsor 11 Park Square 45 Park Square, Leeds 1 Mr. -

Headingley Methodist Church

Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction and Methodology Introduction..........................................................................................................................6 Methodology........................................................................................................................ 9 The History of Headingley Brief History.......................................................................................................................... 11 Religious History of Headingley............................................................................................ 12 The Church of England..........................................................................................................13 Methodism............................................................................................................................14 Roman Catholicism............................................................................................................... 15 Non-conformist Churches.....................................................................................................15 Religious Richness and Secular Care Overview...............................................................................................................................16 Ecumenical -

Leeds City Council and B¡Ll Mckinnon

Statement of Gommon and Uncommon Ground between Leeds City Council and B¡ll McKinnon Reference -Green Space Background Paper (CDL/321 HMCA: lnner (and reference to l site in North) Ward: Hyde Park and Woodhouse (and L site in Chapel Allerton) Name of Representor: Bill McKinnon Representation number(s): PDEO2546 (Publication Draft stage) & PSE00599 (Pre Submission Change stage) Site Allocat¡ons Plan Examination Leeds Local Plan Leeds ffi CITY COUNCIL I 1 Introduction 1.1 This statement of common and uncommon ground has been prepared jointly between Leeds City Council and Bill McKinnon (the parties). 1.2 It sets out matters which Mr McKinnon and Leeds City Council agree on and also identifies specific issues raised by My McKinnon in his oral representation presented atthe Matter4: green space hearing session on24th October 2017 which the Council disagrees with. 2 Background 2.1 Mr McKinnon has expressed a number of concerns about the contents of the various versions of the Green Space Background Paper ln relation to green spacê identification in Hyde Park and Woodhouse Ward and the subsequent calculation of surpluses and deficiencies against the standards set out in Core Strategy Policy G3. He submitted representations at Publication Draft stage (PDE02546) and to the proposed pre-submission changes (PSE00599). The details contained in his representation to the Publication Draft SAP were considered carefully by the City Council and some changes were made (as identified at paragraph 3.1 below). Nevertheless, there remain facts and issues over which the parties disagree which are set out below in paragraph 4.1 3 Areas of Gommon Ground 3.1 The parties are in agreement in respect of the following: Statement Statement from Mr McKinnon Statement from Leeds City of Common Council Ground Number 1) Mr McKinnon promotes the designation The Council agrees with Mr and protection of the open space McKinnon and has proposed adjacent to the former sorting office off pre-submission change number Cliff Road as green space. -

Garmont Court, Chapel Allerton, Leeds, LS7 3LY Garmont Court, Chapel Allerton, Leeds, LS7 3LY

An exclusive development of 7 contemporary apartments Garmont Court, Chapel Allerton, Leeds, LS7 3LY Garmont Court, Chapel Allerton, Leeds, LS7 3LY Garmont Court is an exclusive new development of seven, one and two bedroom apartments, four of which are duplexes with accomodation over two floors, designed in a contemporary style situated in a quiet, popular area adjacent to Chapel Allerton. These architect designed apartments benefit from gas central heating, underfloor heating to the primary floors and bathrooms, designer kitchens and bathrooms and many energy saving features including energy efficient boiler and underfloor heating. Internally the properties have been designed with space in mind. Both ground floor two bedroom apartments benefit from ensuite facilities and all apartments have the added feature of private outside space; at ground floor level, there is a garden and patio area whilst the duplex apartments have a balcony. Apartment 4 offers a fantastic large balcony. With designer kitchens and coordinating Silestone worktops Caple appliances by Maurice Lay are also included. The bathrooms continue this contemporary styling with white sanitary ware and designer fittings. Floor coverings include a choice of engineered oak flooring or carpets to living areas and porcelain tiled floors to kitchens, bathrooms, utility and ensuites. Each property benefits from designated parking. A 10 year warranty is provided by Premier Guarantee. Chapel Allerton Chapel Allerton, a short walk away from the development, is a very popular suburb situated 2 miles to the north east of Leeds City Centre with excellent road links close at hand. The bustling core of Chapel Allerton is a conservation area with many characterful and historic buildings.