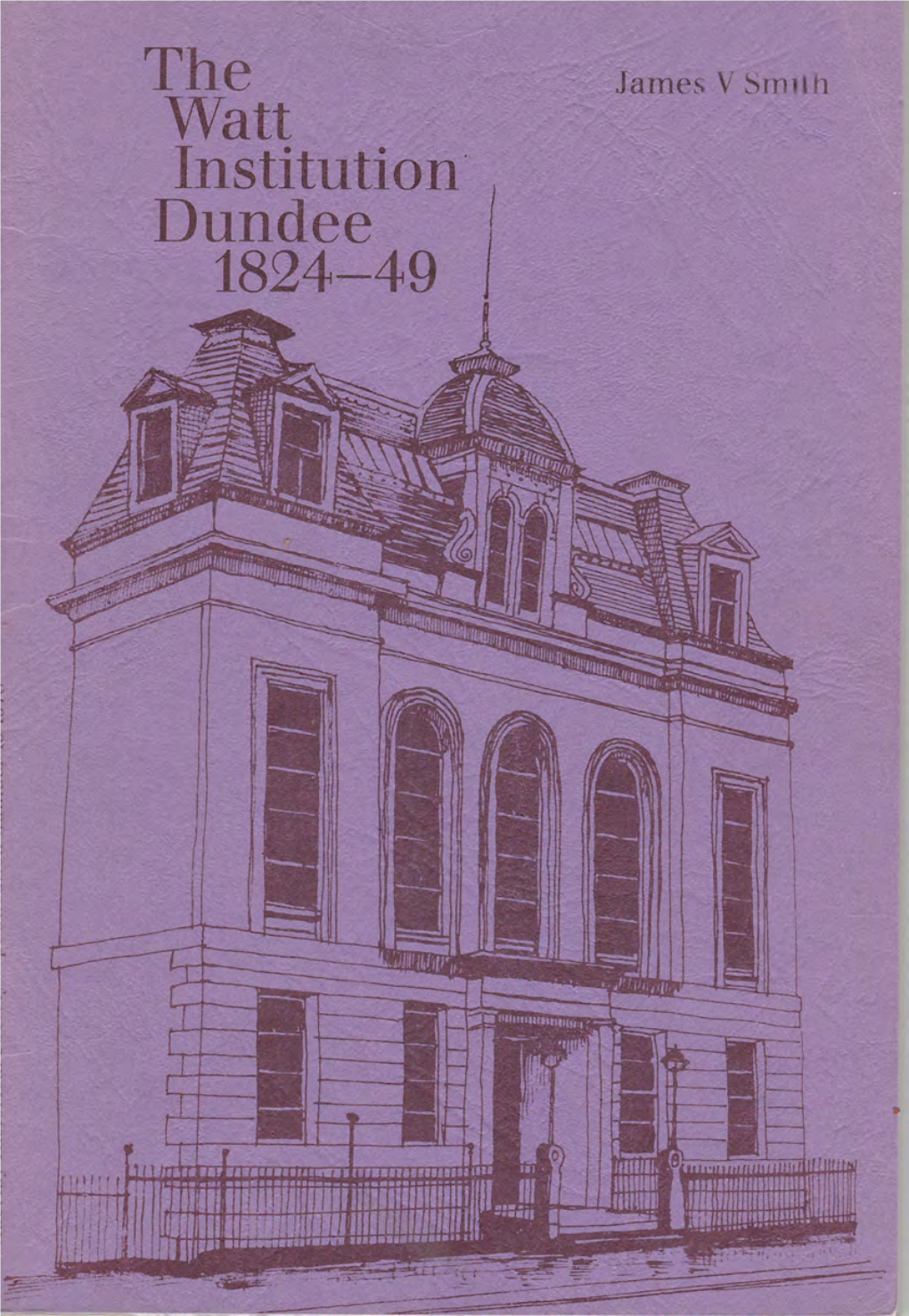

The Watt Institution 1824-49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angeletti, Gioia (1997) Scottish Eccentrics: the Tradition of Otherness in Scottish Poetry from Hogg to Macdiarmid

Angeletti, Gioia (1997) Scottish eccentrics: the tradition of otherness in Scottish poetry from Hogg to MacDiarmid. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2552/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] SCOTTISH ECCENTRICS: THE TRADITION OF OTHERNESS IN SCOTTISH POETRY FROM HOGG TO MACDIARMID by Gioia Angeletti 2 VOLUMES VOLUME I Thesis submitted for the degreeof PhD Department of Scottish Literature Facultyof Arts, Universityof Glasgow,October 1997 ý'i ý'"'ý# '; iý "ý ý'; ý y' ý': ' i ý., ý, Fý ABSTRACT This study attempts to modify the received opinion that Scottish poetry of the nineteenth-centuryfailed to build on the achievementsof the century (and centuries) before. Rather it suggeststhat a number of significant poets emerged in the period who represent an ongoing clearly Scottish tradition, characterised by protean identities and eccentricity, which leads on to MacDiarmid and the `Scottish Renaissance'of the twentieth century. The work of the poets in question is thus seen as marked by recurring linguistic, stylistic and thematic eccentricities which are often radical and subversive. -

Burns Chronicle 1895

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1895 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by the Caledonian Society of Sheffield The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com i&,teotton of Pat.ant o6.. TPade Map • Bl'aneh and Statlonen' Rall Regtatl'B.tlon. SPECIALTY IN WHISKY. "Jlnlb AS SUPPLIED TO THE BRITISH ROYAL COMMISSION, VICTORIA HOUSE, CHICAGO, AND LEADING CLUJIS AND MESSES IN L~DJA. As a Scotch Whisky there is nothing finer than " llul~ Scottie," made from the purest selected material, and blended with the greatest of care. Invalids requiring a genuine stimulant will find in " llul~ Scottie" Whisky one d the purest form. For Medicinal purposes it equals old Brandy. · The "LANCET1' says--" This Whisky contains 41 •75 per cent. of absolute alcohol, equal to 86·28 per cent. of proof spirit. The residue, dried at 100° C., amounts to 0·25 per cent. It is a well matured and excellent whisky." No hlghel' Medical Testimony ls enjoyed by any Bl'and. As a guarantee of the contents, every bottle is enveloped in wire and be&r11 the Proprietor's seal in lead, without which none is genuine. COLUJIBUN EXPOSITION, CHICAGO, 1808. UITBlUU.TIONil BXJIIBITlON, !JLASOOW, 1888. First Award at "World's Fair," Ohioago, For Purity of Quality, Superior Excellence, MellowneSB of Flavour and Highest Standard of Merit. Reffetered Proprietor: JAMES MENZIES, GLASGOW. res:-68 BATH "STREET. 1• ,_"_ ADVERTISEMENTS. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-~~~~~~ ,·:···-1 '1:0 the " Bul'ns Clubs " of Scotland. -

“Spasm” and Class: W. E. Aytoun, George Gilfillan, Sydney Dobell, and Alexander Smith FLORENCE S

“Spasm” and Class: W. E. Aytoun, George Gilfillan, Sydney Dobell, and Alexander Smith FLORENCE S. BOOS HE BRIEF FLORUIT OF THE “SPASMODIC” POETS FOLLOWED CLOSELY ONE OF Tnineteenth-century British radicalism’s most signal defeats—the re- jection of the 1848 People’s Charter. Spasmodic poems also “consistently [took] as their subject a young poet’s struggle to write the poem that would make him famous”1—a conspicuous underlying theme of Wordsworth’s Pre- lude (1850), as well as the first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855). Such personal and collective struggles in fact provided signature- themes for hundreds of English and Scottish working-class and humble life poets of the era, who penned Shelleyan “dream visions,” declaimed in the voice of rustic prophets, and focused their aspirations on the tenuous out- lines of a more democratic culture to come. Melodrama and popular stage productions were also quintessential mid-Victorian working-class genres,2 and political relevance may be found in contemporary critical tendencies to attack the Spasmodic poets for their melodramatic and declamatory extravagance. Sydney Dobell, Alexander Smith, Gerald Massey, and Ebenezer Jones, in particular, were working- or lower-middle class in their origins and edu- cation, and several of these poets had contributed to the democratic fervor which culminated in the People’s Charter of 1848. Under the penname “Bandiera,” for example, Massey had written revolutionary verses, and Jones’s pamphlet on Land Monopoly (1849) anticipated arguments made famous by Henry George in Progress and Poverty two decades later.3 Smith followed with interest the actions of Chartism’s Scottish wing, and Dobell’s first poem, The Roman (1850), celebrated an imaginary hero of Italian in- dependence after the manner of Browning’s Sordello and Bulwer-Lytton’s Rienzi. -

The Presbyterian Interpretation of Scottish History 1800-1914.Pdf

Graeme Neil Forsyth THE PRESBYTERIAN INTERPRETATION OF SCOTTISH HISTORY, 1800- 1914 Ph. D thesis University of Stirling 2003 ABSTRACT The nineteenth century saw the revival and widespread propagation in Scotland of a view of Scottish history that put Presbyterianism at the heart of the nation's identity, and told the story of Scotland's history largely in terms of the church's struggle for religious and constitutional liberty. Key to. this development was the Anti-Burgher minister Thomas M'Crie, who, spurred by attacks on Presbyterianism found in eighteenth-century and contemporary historical literature, between the years 1811 and 1819 wrote biographies of John Knox and Andrew Melville and a vindication of the Covenanters. M'Crie generally followed the very hard line found in the Whig- Presbyterian polemical literature that emerged from the struggles of the sixteenth and seventeenth century; he was particularly emphatic in support of the independence of the church from the state within its own sphere. His defence of his subjects embodied a Scottish Whig interpretation of British history, in which British constitutional liberties were prefigured in Scotland and in a considerable part won for the British people by the struggles of Presbyterian Scots during the seventeenth century. M'Crie's work won a huge following among the Scottish reading public, and spawned a revival in Presbyterian historiography which lasted through the century. His influence was considerably enhanced through the affinity felt for his work by the Anti- Intrusionists in the Church of Scotland and their successorsin the Free Church (1843- 1900), who were particularly attracted by his uncompromising defence of the spiritual independence of the church. -

John and George Armstrong at Edinburgh

JOHN AND GEORGE ARMSTRONG AT EDINBURGH By WILLIAM J. 'MALONEY, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S.E. The medical talent of the Scot which astounded the eighteenth century appeared at times as a family characteristic. Remarkable in successive generations of a Monro, a Rutherford, a Gregory, and a Duncan family, it came close to genius in William and John Hunter, as well as in John Armstrong, the poet-physician, and his brother George the father of modern pediatrics, and the founder of the Dispensary for the Infant Poor, the world's first hospital for children. in The Armstrong brothers were sons of the manse at Castleton Roxburghshire ; and grandsons of a general practitioner in the minor Covenanting centre of Kelso. At the soTemn signing of the Covenant, back in 1638, this Kelso doctor, John Armstrong, was about five years old. He grew up among" the Presbyterian saints who, with faith as almost their sole weapon* defied prelates and kings for over fifty years. In the published accounts of those worthies, no Armstrong is named. Seemingly none of the " clan was called on to testify," or notably suffer, for their cause. If this seventeenth century doctor took part in their struggle f?r ascendancy, his service is unrecorded. But he did send his second " a. son, Robert, to the College of Edinburgh, where the students, as rule, were on the Covenanting side." Intended for the ministry, Robert required Latin, Greek, Logic' and Ethics in order to enter the Divinity Hall. He probably studied these subjects for the usual number of terms, or sessions ; but because of the destruction of the old College archives (Grant, I, 224), all that is now known of his academic career is that he belatedly commenced the course in Divinity, without graduating in Arts. -

Reverend George Gilfillan

THE REVEREND GEORGE GILFILLAN About August 29, 1849 in Emerson’s journal: Love is the bright foreigner, the foreign self. [The Reverend Theodore] Parker thinks, that, to know Plato, you must read Plato thoroughly, & his commentators, &, I think, Parker would require a good drill in Greek history too. I have no objection to hear this urged on any but a Platonist. But when erudition is insisted on to Herbert or Henry More, I hear it as if to know the tree you should make me eat all the apples. It is not granted to one man to express himself adequately more than a few times: and I believe fully, in spite of sneers, in interpreting the French Revolution by anecdotes, though not every diner out can do it. To know the flavor of tanzy, must I eat all the tanzy that grows by the Wall? When I asked Mr Thom in Liverpool — who is Gilfillan? & who is Mac-Candlish? he began at the settlement of the Scotch Kirk in 1300 ? & came down with the history to 1848, that I might understand what was Gilfillan, or what was Edin. Review &c &c. But if a man cannot answer me in ten words, he is not wise.” “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project George Gilfillan HDT WHAT? INDEX THE REVEREND GEORGE GILFILLAN GEORGE GILFILLAN 1733 In this oil on canvas at the National Gallery in London on the popular topic “Time Unveiling Truth,” the winged naked old guy in the sky with a scythe is personifying TIME, and what he is doing is, he is exposing the nipplicious charms of a sweet young thing personifying TRUTH as she likewise reaches out and unmasks a fat old woman personifying FRAUD. -

Chapter One James Mylne: Early Life and Education

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. 2013 THESIS Rational Piety and Social Reform in Glasgow: The Life, Philosophy and Political Economy of James Mylne (1757-1839) By Stephen Cowley The University of Edinburgh For the degree of PhD © Stephen Cowley 2013 SOME QUOTES FROM JAMES MYLNE’S LECTURES “I have no objection to common sense, as long as it does not hinder investigation.” Lectures on Intellectual Philosophy “Hope never deserts the children of sorrow.” Lectures on the Existence and Attributes of God “The great mine from which all wealth is drawn is the intellect of man.” Lectures on Political Economy Page 2 Page 3 INFORMATION FOR EXAMINERS In addition to the thesis itself, I submit (a) transcriptions of four sets of student notes of Mylne’s lectures on moral philosophy; (b) one set of notes on political economy; and (c) collation of lectures on intellectual philosophy (i.e. -

Angus and Mearns Directory and Almanac, 1847

ANGUS - CULTURAL SERVICES 3 8046 00878 6112 This book is to be returned on or before <51 '^1^ the last date stamped below. district libraries THE ANfiDS AND MEARNS DIHECTORY AND ALMANAC CONTAINING, IN ADDfTION Tffl THE WHOLE OF THE LISTS CONNECTED WITH THE COUNTIES OF FORFAR AND KING A.RDINE, AND THE BURGHS OF DUNDEE, MONTROSE, ARBROATH, FORFAR, KIRRIEMUIR, STONEHAVEN, &c. ALPHABETICAL LISTS INHABITANTS OF MONTROSE, ARBROATH, FORFAR, BRECHIN, AND KIRRIEMUIR; TOGKTHER WITH A LIST OF VESSELS REGlSTiSRED AT THE PORTS OF MONTROSE, ARBROATH, DUNDEE, PERTH, ABERDEEN, AND STONEHAVEN. MONTRO SE: . PREPARED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES WATT, standarboffice; EDINBURGH: BLACKWOOD AND SON, AND OLIVER A ND BOYD AND SOI*5i BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. NOTICE. The Publisher begs to intimate that next publication of the l>irectofy will contain, in addition to the usual information, I^ists of all Persons in Business, arranged according to their Trades and Professions. Although this will add considerably to the size of the book, it is not intended to increase its pric£'. —— — CONTENTS. AKSnOATH DlRRCTORV P^^fi, T»ge - Alphabetical List of Names 75 Hiring Markets - - 185 Banks, Public Offices, etc. 90 Kirrifmuir Directory— 98 Coaches, Carriers, etc. - !)1 Alphabetical List of Names - 104 General Lists - - 92—97 Coaches, Carriers, etc. - 104 Parliameniarv Electors - 88 Listuf Public Bodies, etc. Railway Trains, Arrival and Kincardineshire County - 163 Departure of - - - 97 Directory—Constabulary AueliinblaeLists . - 165 Commissioners of Supply and Jus- - • '60 Barrv Lists . - - - 1-22 tices of Peace ^' - - 16S Bervie Lists - - . 168 Commissary Court* Bbschin Directory— Freeholders and Electors - 151 Alphabetical List of Names 55 Game Association - • 164 Banks, Public OSices, etc. -

Poets and Poetry of the Covenant" As This Author

Poets and Poetry OF The Covenant COMl'ILEl), WITH An Intrjoduction BY THE REV. DAVID MCALLISTER, D. D., LL. D. ""^N 201894 % ij ^ ;^- ALLEGHENY, PA. ' COVENAiSTTER PUBLISHING CO. 37 Federal Street 1894 .0^^ ^ Copyright of Covenanter Publishing Co., 1894. TO ADAM B. TODD, WHO, AS ONE OF THE POETS OF THE COVENANT, AND AS AUTHOR OF "HOMES, HAUNTS AND BATTLEFIELDS OF THE COVENANTERS," HAS RENDERED MOST VALUABLE SER- VICE TO THE SAME GLORIOUS CAUSE OF CIVIL AND RELIG- IOUS LIBERTY FOR WHICH THE HEROES AND MAR- TYRS OF THE COVE- NANT SUFFERED AND DIED, This Volume IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED. mw^^F^w^^wwwww^^w^^ fTTy^yr^^^yr GREYFRIARS CHURCHYARD AND EDINBURGH CASTLE. PREFACE. A volume of -'Poetry of the Covenant" had been in the mind of the compiler for nearly forty years. His admiration and study of '• The Cameronian Dream," when but a college student, first suggested such a volume. Acquaintance at a later day with George Gilfillan's " Martyrs, Heroes and Bards of the Scottish Covenant," and Mrs. Menteath"s " Lays of the Covenant," and with a number of other spirited poems copied into the monthly magazine, "The Covenanter," pub- lished in Philadelphia by the Rev. James M. Willson, intensi- fied the desire for such a compilation. But not until the work of preparation for publication was begun did the com- piler dream of the wealth of poetry which the Covenanters and their times had called forth. The book happily styled '• The Treasury of the Covenant," by the Rev. J. C. Johnstoa, of Dunoon, Scotland, published at Edinburgh in 1887, was a revelation of the rich resources of this field of literature. -

Section 3 Below

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. V, October, 1850, Volume I. This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. V, October, 1850, Volume I. Release Date: August 17, 2010 [Ebook 33452] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE, NO. V, OCTOBER, 1850, VOLUME I.*** Harper's New Monthly Magazine No. V.—October, 1850.—Vol. I. Contents Wordsworth—His Character And Genius. .2 Sidney Smith. By George Gilfillan. 19 Thomas Carlyle. By George Gilfillan. 25 The Gentleman Beggar. An Attorney's Story. (From Dickens's Household Words.) . 31 Singular Proceedings Of The Sand Wasp. (From Howitt's Country Year-Book.) . 43 What Horses Think Of Men. From The Raven In The Happy Family. (From Dickens's Household Words.) . 46 The Quakers During The American War. (From Howitt's Country Year-Book.) . 53 A Shilling's Worth Of Science. (From Dickens's House- hold Words.) . 57 A Tuscan Vintage. 66 How To Make Home Unhealthy. By Harriet Martineau. 68 Sorrows And Joys. (From Dickens's Household Words.) . 124 Maurice Tiernay, The Soldier Of Fortune. (From the Dublin University Magazine) . 125 The Enchanted Rock. (From Chambers's Edinburgh Journal.)160 The Force Of Fear. (From Chambers's Edinburgh Journal.) 163 Lady Alice Daventry; Or, The Night Of Crime. -

Memorialising Burns: Dundee and Montrose Compared

Memorialising Burns: Dundee and Montrose compared Christopher A Whatley 1 Introduction This short paper is intended to provide an indication of the kinds of issues that are being explored by the Dundee-led component of the ‘Inventing Tradition and Securing Memory: Robert Burns, 1796-1909’ project. It is a case study. It outlines the story of the campaign for a statue of Robert Burns in Dundee which was waged between 1877 and 1880. It looks at the public reception of the statue when it was unveiled. Was there a tension, a disjunction even, between the statue as designed and in respect of its semiotic function, and the ‘meaning’ of Burns for those who had led the campaign for, contributed to and celebrated the unveiling of, the statue? Which of Burns’ poems and songs were the most influential? Unfortunately little if any of the correspondence surrounding the commissioning and unveiling of the Dundee statue has survived. There is however a fairly rich cache of such materials for Montrose. This is used later in the essay in part to reinforce some of the points made earlier about Dundee, but also to highlight differences in the commissioning processes and progress of the campaigns for the statues in the two Tayside towns. Occasionally, material relating to statues of Burns elsewhere has been included, where this adds something to the analysis. More comprehensive studies will appear in due course. Included too is some information on how statues of Burns were received, both by the public and contemporary art critics. Examined briefly is the subsequent impact of the more critical comments that were made about the Dundee statue. -

Exporting Radicalism Within the Empire: Scots Presbyterian Political Values in Scotland and British North America, C.1815-C.1850

Wallace, Valerie (2010) Exporting radicalism within the empire: Scots Presbyterian political values in Scotland and British North America, c.1815-c.1850. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1749/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Exporting Radicalism within the Empire: Scots Presbyterian Political Values in Scotland and British North America, c.1815 – c.1850 Valerie Wallace M.A., M.Phil. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow September 2009 Abstract This thesis offers a reinterpretation of radicalism and reform movements in Scotland and British North America in the first half of the nineteenth century by examining the relationship between Presbyterian ecclesiology and political action. It considers the ways in which Presbyterian political theory and the memory of the seventeenth-century Covenanting movement were used to justify political reform. In particular it examines attitudes in Scotland to Catholic emancipation, the Reform Act of 1832, the disestablishment of the national Churches, and the Chartist movement; and it considers agitation in Upper Canada and Nova Scotia for the disestablishment of the established Church and the institution of responsible government.