Gustav Mahler and Hungary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra

issue 01 december 2010 News from the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra We hope that this reaches deeply to connect with the music lover in all of you, our Friends, and the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra. We encourage you to submit your own thoughts and feedback on the BFO or Ivan Fischer’s concerts around the world. We hope that your travel plans will coincide with some of them. On behalf of the Friends of the BFO, we look forward to seeing you at one of the BFO concerts or Galas. Please help us to support the Budapest Festival Orchestra – a very special and talented group of musicians. Details on how you can contribute are on the back of this newsletter! We look forward to seeing more of you! The Friends of the program Budapest Festival Orchestra Gala January 26, 2011 Dinner 6:00 pm Concert 8:00 pm Lincoln Center, Avery Fisher Hall Stravinsky: Scherzo a la Russe This is the third gala sponsored by the Friends of Stravinsky: Tango the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and this year the Haydn : Cello Concerto in C Major program is fantastic with Maestro Ivan Fischer Miklos Perenyi, cello conducting Stravinsky and Haydn. Haydn: Symphony No. 92 The Dinner before the concert is being chaired Stravinsky: Suite from “The Firebird” this year by Daisy M. Soros and Cynthia M. Whitehead. Nicola Bulgari is the Honorary Single Sponsor ticket Patron Table of ten $1,000 each $10,000 Chairman. Buy your tickets now! Send in the Single Patron ticket Benefactor Table of ten enclosed envelope today! $1,500 each $15,000 A Greeting From Ivan Fischer music director of the bfo It is hard to believe that 27 years have passed since I brought into reality a personal dream, the founding of a top-level symphony orchestra in Budapest. -

Ivan Fischer Interview: Budapest Festival Orchestra and His Revolutionary Way with Opera the Conductor Is Turning Opera on Its Head with His Bold and Joyous Attitude

MENU CLASSICAL Ivan Fischer interview: Budapest Festival Orchestra and his revolutionary way with opera The conductor is turning opera on its head with his bold and joyous attitude. And the crowds are loving it Bryan Appleyard ‘There is something about being close to each other’: from left, Yvonne Naef, Sylvia Schwartz, Eva Mei, Laura Polverelli, Ivan Fischer and the BFO in Falstaff JUDIT HORVATH The Sunday Times, November 4 2018, 12:01am Share Save t’s Verdi, an aria from The Sicilian Vespers. The orchestra is playing, the soprano is singing. Then, without warning, all I the players stand up and sing the chorus. The audience gasps. The next night, it’s Verdi’s opera Falsta, and this time the audience just keeps gasping. The characters intertwine and react with the orchestra. They argue with the conductor, who grins and tut-tuts and, when Falsta hits rock bottom, gives him a cloth and a cup of wine. All of which would be amazing enough. But there is also the MENU thrilling fact that Falsta was Verdi’s last opera, and I am watching it in the last building of Andrea Palladio, arguably the greatest and certainly the most influential architect who ever lived. This first Vicenza Opera Festival at the Teatro Olimpico consists of two performances of Falsta and a gala concert. The conductor Ivan Fischer created the shows and brought his Budapest Festival Orchestra, which he set up in 1983 as an annual-festival institution. It became a permanent orchestra in 1992, but he kept the word “festival” in the title. -

Ivan Fischer

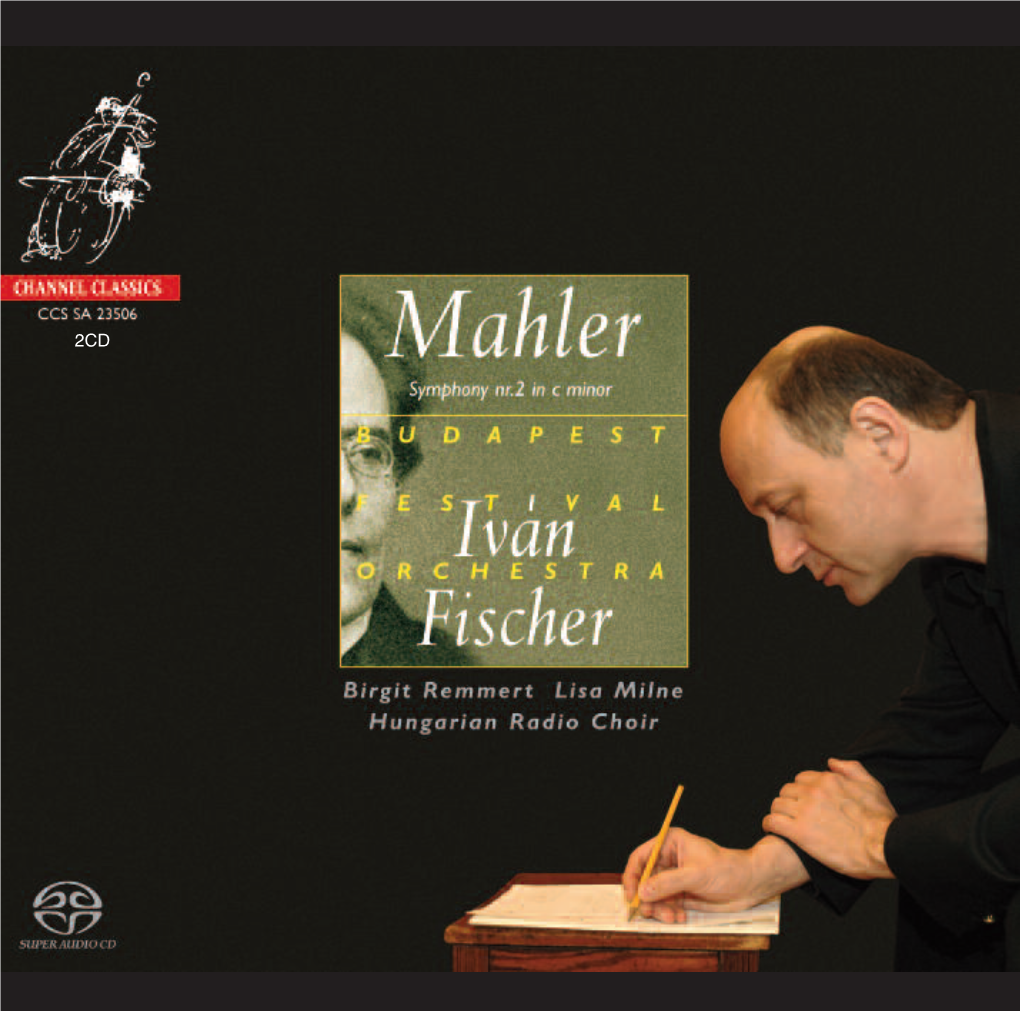

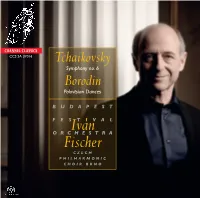

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 37016 Tchaikovsky Symphony no. 6 Borodin Polovtsian Dances BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer CZECH PHILHARMONIC CHOIR BRNO Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is the founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, as well as the IMusic Director of the Konzerthaus and Konzerthausorchester Berlin. In recent years he has also gained a reputation as a composer, with his works being performed in the United States, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Germany and Austria. What is more, he has directed a number of successful opera productions. The BFO’s frequent worldwide tours and a series of critically acclaimed and fast selling records, released first by Philips Classics and later by Channel Classics, have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most high-profile music directors. Fischer has guest-conducted the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times; every year he spends two weeks with Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; and as a conductor, he is also a frequent guest of the leading US symphonic orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra. As Music Director, he has led the Kent Opera and the Opéra National de Lyon, and was Principal Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC. Many of his recordings have been awarded prestigious international prizes. He studied piano, violin, and later the cello and composition in Budapest, before continuing his education in Vienna where he studied Conducting under Hans Swarowsky. Iván Fischer is a founder of the Hungarian Mahler Society and Patron of the British Kodály Academy. -

Hifi/Stereo Review July 1959

• 99 BEST BUYS IN STEREO DISCS DAS RHEINGOLD - FINALLY I REVIEW July 1959 35¢ 1 2 . 3 ALL-IN-ONE STEREO RECEIVERS A N II' v:)ll.n EASY OUTDOOR HI-FI lAY 'ON W1HQI H 6 1 ~Z SltnOH l. ) b OC: 1 9~99 1 1 :1 HIS I THE AR THE HARMAN-KARDON STERE [ Available in three finishes: copper, brass and chrome satin the new STEREO FESTIVAL, model TA230 Once again Harman-Kardon has made the creative leap which distinguishes engineering leadership. The new Stereo Festival represents the successful crystallization of all stereo know-how in a single superb instrument. Picture a complete stereophonic electronic center: dual preamplifiers with input facility and control for every stereo function including the awaited FM multiplex service. Separate sensitive AM and FM tuners for simulcast reception. A great new thirty watt power amplifier (60 watts peak) . This is the new Stereo Festival. The many fine new Stereo Festival features include: new H-K Friction-Clutch tone controls to adjust bass and treble separately for each channel. Once used to correct system imbalance, they may be operated as conventionally ganged controls. Silicon power supply provides excellent regulation for improved transient response and stable tuner performance. D.C. heated preamplifier filaments insure freedom from hum. Speaker phasing switch corrects for improperly recorded program material. Four new 7408 output tubes deliver distortion-free power from two highly conservative power amplifier circuits. Additional Features: Separate electronic tuning bars for AM and FM; new swivel high Q ferrite loopstick for increased AM sensitivity; Automatic Frequency Control, Contour Selector, Rumble Filter, Scratch Filter, Mode Switch, Record-Tape Equalization Switch, two high gain magnetic inputs for each channel and dramatic new copper escutcheon. -

Ivan Fischer

CCSSA31111Booklet 21-03-2011 13:34 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 31111 Schubert Symphony no. 9 (‘Great’) in C major Five German Dances BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer CCSSA31111Booklet 21-03-2011 13:34 Pagina 2 Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra and Principal Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington D.C. He has been Iappointed Principal Conductor of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin starting the season 2012/13. The partnership between Iván Fischer and his Budapest Festival Orchestra has proved to be one of the greatest success stories in the past 25 years of classical music. Fischer introduced several reforms, developed intense rehearsal methods for the musicians, emphasizing chamber music and creative work for each orchestra member. Intense international touring and a series of acclaimed recordings for Philips Classics, later for Channel Classics have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most visionary and successful orchestra leaders. He has developed and introduced new types of concerts, ‘cocoa-concerts’ for young children, ‘surprise’ concerts where the programme is not announced, ‘one forint concerts’ where he talks to the audience, open-air concerts in Budapest attracting tens of thousands of people, as well as concert opera performances applying scenic elements. He has founded several festivals, including a summer festival in Budapest on baroque music and the Budapest Mahlerfest which is also a forum for commissioning and presenting new compositions. As a guest conductor Fischer works with the finest symphony orchestras of the world. He has been invited to the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times and he performs with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra two weeks a year. -

Trinity College Chapel Cambridge, Uk

THE CZECH TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC ORCHESTRA TRINITY COLLEGE CHAPEL CAMBRIDGE, UK THE CONCERT IS HELD UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF MR. LIBOR SEČKA, CZECH AMBASSADOR TO THE UK, MS DENISE WADDINGHAM, THE DIRECTOR OF BRITISH COUNCIL CZECH REPUBLIC, AND MR. GUY ROBERTS, THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE PRAGUE SHAKESPEARE COMPANY BY KIND PERMISSION OF THE MASTER AND FELLOWS OF TRINITY COLLEGE. THE CZECH TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY CONCERT IN PRAGUE (CTU) PROGRAMME is one of the biggest and oldest technical The concert will be introduced by Vojtěch universities in Europe. It was founded on Petráček, rector of the Czech Technical the initiative of Josef Christian Willenberg University in Prague and Nick Kingsbury, on the basis of a decree issued by Emper- Professor of Signal Processing of the Uni- or Josef I. on January 18th, 1707. versity of Cambridge, Dept of Engineering. CTU currently has eight faculties (Civil En- Jean-Joseph Mouret gineering, Mechanical Engineering, Elec- Fanfares trical Engineering, Nuclear Science and Physical Engineering, Architecture, Trans- Jan Dismas Zelenka portation Sciences, Biomedical Engineer- Salve Regina ing, Information Technology) and about 16,000 students. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Gallimathias Musicum For the 2018/19 academic year, CTU of- fers its students 169 study programmes Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and 480 fields of study within these pro- The Nutcracker grammes. CTU educates modern spe- cialists, scientists and managers with Francois Doppler knowledge of foreign languages, who are Andante and Rondo dynamic, flexible and able to adapt rap- idly to the requirements of the market. Bedřich Smetana Waltz No. 1 CTU currently occupies the following po- sitions according to QS World University Antonín Dvořák Rankings, which evaluated more than Biblical Songs No. -

CCSSA 25807 Booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1

CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 25807 Pieter Wispelwey violoncello Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer conductor Dvořák Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in b minor Op.104 Symphonic Variations for orchestra Op.78 CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 2 “Deeply communicative and highly individual performances.” New York Times “An outstanding cellist and a really wonderful musician” Gramophone “An agile technique and complete engagement with the music” New York Times CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 3 Pieter Wispelwey is among the first of a generation of performers who are equally at ease on the modern or the period cello. His acute stylistic awareness, combined with a truly original inter- pretation and a phenomenal technical mastery, has won the hearts of critics and public alike in repertoire ranging from JS Bach to Elliott Carter. Born in Haarlem, Netherlands, Wispelwey’s sophisticated musical personality is rooted in the training he received: from early years with Dicky Boeke and Anner Bylsma in Amsterdam to Paul Katz in the USA and William Pleeth in Great Britain. In 1992 he became the first cellist ever to receive the Netherlands Music Prize, which is awarded to the most promising young musician in the Netherlands. Highlights among future concerto performances include return engagements with the Rotterdam Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Dublin National Symphony, Copenhagen Philharmonic, Sinfonietta Cracovia, debuts with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Bordeaux National Orchestra, Strasbourg Philharmonic, Tokyo Symphony and Sapporo Symphony, as well as extensive touring in the Netherlands with the BBC Scotish Symphony and across Europe with the Basel Kammer- orchester to mark Haydn’s anniversary in 2009. -

Holiday Classics: Nutcracker Sweet 2018-19 Hal & Jeanette Segerstrom Family Foundation Classical Series

HOLIDAY CLASSICS: NUTCRACKER SWEET 2018-19 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES Pacifi c Symphony Brahms PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 Carl St.Clair, conductor Allegro non troppo Markus Groh, piano Allegro appassionato Andante Allegretto grazioso Markus Groh Vaughan Williams FANTASIA ON A THEME BY THOMAS TALLIS Intermission Tchaikovsky SELECTIONS FROM TCHAIKOVSKY’S THE NUTCRACKER AND ARRANGEMENTS OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S MUSIC BY DUKE ELLINGTON AND BILLY STRAYHORN Overture – Original & Ellington/Strayhorn Versions March of the Toy Soldiers – Original Sugar Rum Cherry – Ellington/Strayhorn Trepak (Russian Dance) – Original Volga Vouty ‑ Ellington/Strayhorn Coffee (Arabian Dance) – Original Tea (Chinese Dance) – Original Toot Toot Tootie Toot – Ellington/Strayhorn Dance of the Reed Flutes – Original The Waltz of the Flowers/Dance of the Floreadores – Original & Ellington/Strayhorn Preview talk with Alan Chapman at 7 p.m. Thursday, December 6, 2018 @ 8 p.m. Friday, December 7, 2018 @ 8 p.m. Saturday, December 8, 2018 @ 8 p.m. Segerstrom Center for the Arts This performance is generously sponsored by the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall Michelle F. Rohé Distinguished Pianists Fund. Offi cial Hotel Offi cial TV Station Offi cial Classical Music Station This concert is being recorded for broadcast on Sunday, Feb. 24, 2019, at 7 p.m. on Classical KUSC. 1 PROGRAM NOTES JOHANNES BRAHMS: with immediate success. PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 This concerto is a work of virtuosic demands but not of virtuosic display. One RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: When Brahms began formidable challenge for the soloist lies in FANTASIA ON A THEME BY sketching themes for his its four-movement form: not just a test of THOMAS TALLIS Piano Concerto No. -

Aus Der Neuen Welt Aus Der Neuen Welt

Sonntag, 19. Juni 2011 · 17.00 Uhr · Klosterkirche Mariental Samstag, 25. Juni 2011 · 19.00 Uhr · Kaiserdom Königslutter Chor- und Orchesterkonzert Aus der neuen Welt Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Messe D-Dur op. 86 Kyrie Gloria Credo Sanctus Benedictus Agnus Dei Symphonie Nr. 9 e-Moll op. 95 „Aus der neuen Welt“ Allegro - Allegro molto Largo Scherzo. Molto vivace Allegro con fuoco Te Deum op. 103 Te deum laudamus Tu rex gloria Aeterna fac cum sanctis tuis Dignare domine · · · Danuta Dulska (Sopran) Kathrin Hildebrandt (Alt) Jörn Lindemann (Tenor) Peter Schüler (Bass-Bariton) Michael Vogelsänger (Orgel) Helmstedter Kammerchor Propsteikantorei Königslutter Camerata Instrumentale Berlin Leitung: Andreas Lamken (19. Juni) und Matthias Wengler (25. Juni) DANUTA DULSKA wurde in Danzig geboren. Nach dem Be- such des Musikgymnasiums absolvierte sie ihr Studium an der Staatlichen Musikakademie Danzig in den Fächern Kla- vier, Sologesang und Schauspiel. Das Konzertexamen für Sologesang legte sie an der Hoch- schule für Musik in Dresden in der Klasse von Prof. Christian Elsner erfolgreich ab. Weitere Studien führten sie u. a. zu: Adele Stolte (Potsdam), André Orlowitz (Kopenhagen), Neil Semer (New York), Helmut Kretschmar (Detmold). Von 1990 bis 1995 war sie als Dozentin für Liedbegleitung und später für Gesang an der Musikakademie Danzig tätig. Von 1996 bis 1999 war sie Ensemblemitglied an der Staats- oper Hamburg. Zurzeit arbeitet sie als Lehrerin für Gesang und Klavier an der Musischen Akademie im CJD Braunschweig sowie an der Braunschweiger Domsingschule. Seit 1989 tritt Danuta Dulska international als Konzert- und Oratoriensängerin auf, u. a. in Deutschland, Polen, Holland, Finnland, Schweden, Frankreich, Russland, Tschechien, der Schweiz und der Slowakei, wo sie auch bei Rundfunkaufnahmen und Live-Übertra- gungen mitgewirkt hat. -

Findbuch Als

Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort II 1.0 Orgelkonzerte 1 2.0 Internationale Orgeltage 24 3.0 Geistliche Konzerte 57 4.0 Weihnachtsmusik / Christmetten 90 5.0 Pfingstkonzerte 105 6.0 Passionsmusik 110 7.0 Besondere Anlässe 126 8.0 Einzelne Komponisten 135 8.1 Bach 136 8.2 Haydn 139 8.3 Händel 141 9.0 Sonstiges 144 I Vorwort Vorwort Der Bestand setzt sich aus digitalisierten Aufnahmen der Marienkantorei zu- sammen. Vorhanden sind v.a. diverse Konzertmitschnitte von Auftritten der Marienkantorei oder befreundeter Künstler/Gruppen. Wer im Einzelnen die Mitschnitte angefertigt hat, ist unklar. Die Digitalisierung der analogen Vorlagen erfolgte über die MarienKantorei. Die Tonaufnahmen liegen als wav-Dateien vor. Die eigentlichen Audioaufnahmen (Tonbänder, Tonkassetten...) befinden sich im Bestand NL 12 Nachlass Marienkantorei Lemgo/Kantor Walther Schmidt. Benutzung des Bestandes Die Benutzung des Bestandes (d.h. das Hören der Digitalaufnahmen) erfolgt nur nach vorheriger Genehmigung durch den Vorstand der MarienKantorei Lemgo im Benutzersaal des Stadtarchivs. Verweis Das Schriftgut und Bild/Videomaterial der Marienkantorei Lemgo befindet sich im Bestand NL 12 - Nachlass Marienkantorei Lemgo/Kantor Walther Schmidt. Dort auch weitere Verweise und Literaturangaben. II 1.0 Orgelkonzerte 1.0 Orgelkonzerte NL 12 a - Kass. C5 Byrd-Fantasia Byrd - In Assumptione - Beatae Mariae Virginis Messeproprius Vokalensemble Chanticleer-Nicholas Danby St.Marien MarienKantorei Digitalisat auf mobiler Festplatte Nr. 1 2015/008 NL 12 a - 11.3.8 Lieder und Dvorak-Messe Johannes Homburg,Orgel St.Marien MarienKantorei Digitalisat auf mobiler Festplatte Nr. 1 2015/008 NL 12 a - 18.98 02.11.1958 Chor- und Orgelkonzert des Pres:Kyrie, Sanctus und Agnus dei aus Missa de beata virgine, Brixi: Concerto F-dur, Reichel: Con- certo f.Orgel, Muffat: Toccata Nr. -

FRENCH KLEINDEUT8CH POLICY in 1848. the University Of

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 6 8» 724 CHASTAIN, James Garvin, 1939- FRENCH KLEINDEUT8CH POLICY IN 1848. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1967 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ©COPYRIGHT BY JAMES GARVIN CHASTAIN 1968 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE FRENCH KLEINDEUTSCH POLICY IN 1848 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JAMES GARVIN CHASTAIN Norman, Oklahoma 1967 FRENCH KLEINDEUTSCH POLICY IN 1848 APPROVED BY A • l \ ^ DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PREFACE This work is the outgrowth of an interest in French Diplomatic History and 1848 which I experienced under the questioning encourage ment of Professor Brison D. Gooch. I have especially appreciated the helpful suggestions of Professor William Savage. I am indebted to Professors William H. Maehl and Kenneth I, Dailey for their demanding insistence on detail and fact which balanced an earlier training in broad generalization by Professors H. Stuart Hughes, John Gaus and Herbert Spiro. For the idea of the French missionary feeling to export liberty, which characterized Lamartine and Bastide, the two French Foreign Ministers of 1848, I must thank the stimulating sem inar at the University of Munich with Dr. Hubert Rumpel, To all of these men I owe a deep gratitude in helping me to understand history and the men that have guided politics. I want to thank the staff of the French Archives of the Min istry of Foreign Affairs, which was always efficient, helpful and friendly even in the heat of July. Mr. -

Hosch News 01-07

01 HOSCH news 2008 The International HOSCH Magazine • HOSCH Power for Poland’s Energy Network • HOSCH do Brasil at Full Throttle Technology convincing in power and mining industries Daughter company celebrates 10th anniversary • New Warehouse Extends Headquarters • HOSCH S.A. Produce HD Prototype Factory II creates space for new products First trial runs look promising www.hosch.de 02 HOSCH news Editorial selves just as strongly to the well-being of our employees. That way, we will manage to grow further as a world-wide family Score Points with Innovations of companies. Dear HOSCH employees! Every day, the HOSCH companies around the world show how successful good teamwork is and what an important part Innovations and constant improvement of the individual per- motivated and satisfied employees play – from the youngest formance is the key to success in a further globalising and HOSCH company in Italy to the eldest daughter company in rapidly progressing world. HOSCH accepts this challenge South Africa. Through their great effort, all of them make a with pleasure. With our innovative products and our full considerable contribution to the success of the HOSCH family service we have succeeded in strengthening our position on of companies. We would like to thank you for all your com- the world-wide markets and even expanding our business. mitment – and assure you that we will do anything within our powers to make our own contribution to the growth and inno- Innovations are the driving force behind success – this is re- vations through constant investment in product improvements flected in the latest issue of the HOSCH news.