Mahler Benjamin Zander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday 16 September 1.00Pm Dame Sarah Connolly Mezzo-Soprano Malcolm Martineau Piano

Wednesday 16 September 1.00pm Dame Sarah Connolly mezzo-soprano Malcolm Martineau piano Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Banalités (1940) (Guillaume Apollinaire) Chanson d’Orkenise Song of Orkenise Par les portes d’Orkenise Through the gates of Orkenise Veut entrer un charretier. a waggoner wants to enter. Par les portes d’Orkenise Through the gates of Orkenise Veut sortir un va-nu-pieds. a vagabond wants to leave. Et les gardes de la ville And the sentries guarding the town Courant sus au va-nu-pieds: rush up to the vagabond: ‘ – Qu’emportes-tu de la ville?’ ‘What are you taking from the town?’ ‘ – J’y laisse mon cœur entier.’ ‘I’m leaving my whole heart behind.’ Et les gardes de la ville And the sentries guarding the town Courant sus au charretier: rush up to the waggoner: ‘ – Qu’apportes-tu dans la ville?’ ‘What are you carrying into the town?’ ‘ – Mon cœur pour me marier.’ ‘My heart in order to marry.’ Que de cœurs dans Orkenise! So many hearts in Orkenise! Les gardes riaient, riaient, The sentries laughed and laughed: Va-nu-pieds la route est grise, vagabond, the road’s not merry, L’amour grise, ô charretier. love makes you merry, O waggoner! Les beaux gardes de la ville, The handsome sentries guarding the town Tricotaient superbement; knitted vaingloriously; Puis, les portes de la ville, the gates of the town then Se fermèrent lentement. slowly closed. Hôtel Hotel Ma chambre a la forme d’une cage My room is shaped like a cage Le soleil passe son bras par la fenêtre the sun slips its arm through the window Mais moi qui veux fumer pour -

From the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra

issue 01 december 2010 News from the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra We hope that this reaches deeply to connect with the music lover in all of you, our Friends, and the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra. We encourage you to submit your own thoughts and feedback on the BFO or Ivan Fischer’s concerts around the world. We hope that your travel plans will coincide with some of them. On behalf of the Friends of the BFO, we look forward to seeing you at one of the BFO concerts or Galas. Please help us to support the Budapest Festival Orchestra – a very special and talented group of musicians. Details on how you can contribute are on the back of this newsletter! We look forward to seeing more of you! The Friends of the program Budapest Festival Orchestra Gala January 26, 2011 Dinner 6:00 pm Concert 8:00 pm Lincoln Center, Avery Fisher Hall Stravinsky: Scherzo a la Russe This is the third gala sponsored by the Friends of Stravinsky: Tango the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and this year the Haydn : Cello Concerto in C Major program is fantastic with Maestro Ivan Fischer Miklos Perenyi, cello conducting Stravinsky and Haydn. Haydn: Symphony No. 92 The Dinner before the concert is being chaired Stravinsky: Suite from “The Firebird” this year by Daisy M. Soros and Cynthia M. Whitehead. Nicola Bulgari is the Honorary Single Sponsor ticket Patron Table of ten $1,000 each $10,000 Chairman. Buy your tickets now! Send in the Single Patron ticket Benefactor Table of ten enclosed envelope today! $1,500 each $15,000 A Greeting From Ivan Fischer music director of the bfo It is hard to believe that 27 years have passed since I brought into reality a personal dream, the founding of a top-level symphony orchestra in Budapest. -

Upbeat Autumn 2011

The Magazine for the Royal College of MusicI Autumn 2011 What’s inside... Welcome to upbeat… This issue we’re celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Britten Theatre, so we’ve been out and about collecting memories from those involved in the Contents opening of this much-loved venue. 4 In the news The theatre was opened in November 1986 with three spectacular gala concerts. Hidden away in the chorus was none other than leading mezzo- Updating you on recent College activities including museum soprano Sarah Connolly! Turn to page 11 to hear her memories of performing developments and competition with leaping Lords and dancers dressed as swans, all in aid of raising funds for successes the theatre. We also talk to Leopold de Rothschild, who as Chairman of the Centenary 9 New arrivals Appeal, played a significant role in making sure the project came to fruition. The RCM welcomes a host of new On page 14, he remembers conducting the RCM Symphony Orchestra and faces to the College reveals what the Queen said to him on opening night… We’re always keen to hear from students past and present, particularly if you 10 The Britten Theatre… the perfect showcase have any poignant memories of the Britten Theatre. Send your news and pictures to [email protected] by 9 January 2012 to be featured in the next As we celebrate 25 years of the edition of Upbeat. Britten Theatre, Upbeat discovers how the College is seeking ways to update and improve it for the NB: Please note that we cannot guarantee to include everything we receive and that we 21st century reserve the right to edit submissions. -

PRESS RELEASE for Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release MAAZEL: MAHLER CYCLE 2011 London’s only complete Mahler symphony cycle led by a single conductor 2011 is a year of major worldwide Mahler celebrations and the Philharmonia Orchestra is marking this event by bringing Lorin Maazel, one of the world’s finest Mahlerians, to London to perform a heroic one-man journey through all ten Mahler symphonies and four major orchestral song cycles over ten concerts from April-October 2011. Maazel and the Philharmonia presented the first complete Mahler symphony cycle in London 33 years ago, in 1978-9. This series also includes concerts in Basingstoke, Bristol, Gateshead, Hull, Manchester and Warwick, a 13-concert tour to France, Germany, Italy and Luxembourg and a tour of the Far East in spring 2012. As the only full symphony cycle in London taking place with a single conductor, this promises to be a very special exploration of the work of the great composer. Soloists include Michelle DeYoung, Simon Keenlyside, Sarah Fox, Matthias Goerne, Stefan Vinke and Sarah Connolly. The series also includes the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Rückert- Lieder, Des Knaben Wunderhorn and Das Lied von der Erde. Lorin Maazel said of Mahler, and of his own relationship with Mahler’s music: “He was a complete human being who had this genius for spanning the complete gamut of human emotions in sound. It’s the human quality, the person behind the notes as well as the music behind the notes that fascinates me. I really feel as if I’ve come to know Gustav Mahler, the person, intimately -

04 July 2020

04 July 2020 12:01 AM John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) Stars & Stripes forever – March Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra, Richard Dufallo (conductor) NLNOS 12:05 AM Thomas Demenga (1954-) Summer Breeze Andrea Kolle (flute), Maria Wildhaber (bassoon), Sarah Verrue (harp) CHSRF 12:13 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in C major, RV.444 for recorder, strings & continuo Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (recorder), Giovanni Antonini (director), Enrico Onofri (violin), Marco Bianchi (violin), Duilio Galfetti (violin), Paolo Beschi (cello), Paolo Rizzi (violone), Luca Pianca (theorbo), Gordon Murray (harpsichord), Duilio Galfetti (viola) DEWDR 12:23 AM Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) 3 Chansons for unaccompanied chorus BBC Singers, Alison Smart (soprano), Judith Harris (mezzo soprano), Daniel Auchincloss (tenor), Stephen Charlesworth (baritone), Stephen Cleobury (conductor) GBBBC 12:30 AM Bela Bartok (1881-1945) Out of Doors, Sz.81 David Kadouch (piano) PLPR 12:44 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Rosamunde (Ballet Music No 2), D 797 Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Heinz Holliger (conductor) NONRK 12:52 AM John Cage (1912-1992) In a Landscape Fabian Ziegler (percussion) CHSRF 01:02 AM Jean-Francois Dandrieu (1682-1738) Rondeau 'L'Harmonieuse' from Pieces de Clavecin Book I Colin Tilney (harpsichord) CACBC 01:08 AM Bohuslav Martinu (1890-1959) The Frescoes of Piero della Francesca Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Robert Stankovsky (conductor) SKSR 01:30 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings (AV.142) Risor Festival Strings, -

Ivan Fischer Interview: Budapest Festival Orchestra and His Revolutionary Way with Opera the Conductor Is Turning Opera on Its Head with His Bold and Joyous Attitude

MENU CLASSICAL Ivan Fischer interview: Budapest Festival Orchestra and his revolutionary way with opera The conductor is turning opera on its head with his bold and joyous attitude. And the crowds are loving it Bryan Appleyard ‘There is something about being close to each other’: from left, Yvonne Naef, Sylvia Schwartz, Eva Mei, Laura Polverelli, Ivan Fischer and the BFO in Falstaff JUDIT HORVATH The Sunday Times, November 4 2018, 12:01am Share Save t’s Verdi, an aria from The Sicilian Vespers. The orchestra is playing, the soprano is singing. Then, without warning, all I the players stand up and sing the chorus. The audience gasps. The next night, it’s Verdi’s opera Falsta, and this time the audience just keeps gasping. The characters intertwine and react with the orchestra. They argue with the conductor, who grins and tut-tuts and, when Falsta hits rock bottom, gives him a cloth and a cup of wine. All of which would be amazing enough. But there is also the MENU thrilling fact that Falsta was Verdi’s last opera, and I am watching it in the last building of Andrea Palladio, arguably the greatest and certainly the most influential architect who ever lived. This first Vicenza Opera Festival at the Teatro Olimpico consists of two performances of Falsta and a gala concert. The conductor Ivan Fischer created the shows and brought his Budapest Festival Orchestra, which he set up in 1983 as an annual-festival institution. It became a permanent orchestra in 1992, but he kept the word “festival” in the title. -

Ivan Fischer

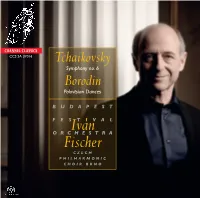

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 37016 Tchaikovsky Symphony no. 6 Borodin Polovtsian Dances BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer CZECH PHILHARMONIC CHOIR BRNO Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is the founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, as well as the IMusic Director of the Konzerthaus and Konzerthausorchester Berlin. In recent years he has also gained a reputation as a composer, with his works being performed in the United States, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Germany and Austria. What is more, he has directed a number of successful opera productions. The BFO’s frequent worldwide tours and a series of critically acclaimed and fast selling records, released first by Philips Classics and later by Channel Classics, have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most high-profile music directors. Fischer has guest-conducted the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times; every year he spends two weeks with Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; and as a conductor, he is also a frequent guest of the leading US symphonic orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra. As Music Director, he has led the Kent Opera and the Opéra National de Lyon, and was Principal Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC. Many of his recordings have been awarded prestigious international prizes. He studied piano, violin, and later the cello and composition in Budapest, before continuing his education in Vienna where he studied Conducting under Hans Swarowsky. Iván Fischer is a founder of the Hungarian Mahler Society and Patron of the British Kodály Academy. -

Ivan Fischer

CCSSA31111Booklet 21-03-2011 13:34 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 31111 Schubert Symphony no. 9 (‘Great’) in C major Five German Dances BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer CCSSA31111Booklet 21-03-2011 13:34 Pagina 2 Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra and Principal Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington D.C. He has been Iappointed Principal Conductor of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin starting the season 2012/13. The partnership between Iván Fischer and his Budapest Festival Orchestra has proved to be one of the greatest success stories in the past 25 years of classical music. Fischer introduced several reforms, developed intense rehearsal methods for the musicians, emphasizing chamber music and creative work for each orchestra member. Intense international touring and a series of acclaimed recordings for Philips Classics, later for Channel Classics have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most visionary and successful orchestra leaders. He has developed and introduced new types of concerts, ‘cocoa-concerts’ for young children, ‘surprise’ concerts where the programme is not announced, ‘one forint concerts’ where he talks to the audience, open-air concerts in Budapest attracting tens of thousands of people, as well as concert opera performances applying scenic elements. He has founded several festivals, including a summer festival in Budapest on baroque music and the Budapest Mahlerfest which is also a forum for commissioning and presenting new compositions. As a guest conductor Fischer works with the finest symphony orchestras of the world. He has been invited to the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times and he performs with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra two weeks a year. -

Trinity College Chapel Cambridge, Uk

THE CZECH TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC ORCHESTRA TRINITY COLLEGE CHAPEL CAMBRIDGE, UK THE CONCERT IS HELD UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF MR. LIBOR SEČKA, CZECH AMBASSADOR TO THE UK, MS DENISE WADDINGHAM, THE DIRECTOR OF BRITISH COUNCIL CZECH REPUBLIC, AND MR. GUY ROBERTS, THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE PRAGUE SHAKESPEARE COMPANY BY KIND PERMISSION OF THE MASTER AND FELLOWS OF TRINITY COLLEGE. THE CZECH TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY CONCERT IN PRAGUE (CTU) PROGRAMME is one of the biggest and oldest technical The concert will be introduced by Vojtěch universities in Europe. It was founded on Petráček, rector of the Czech Technical the initiative of Josef Christian Willenberg University in Prague and Nick Kingsbury, on the basis of a decree issued by Emper- Professor of Signal Processing of the Uni- or Josef I. on January 18th, 1707. versity of Cambridge, Dept of Engineering. CTU currently has eight faculties (Civil En- Jean-Joseph Mouret gineering, Mechanical Engineering, Elec- Fanfares trical Engineering, Nuclear Science and Physical Engineering, Architecture, Trans- Jan Dismas Zelenka portation Sciences, Biomedical Engineer- Salve Regina ing, Information Technology) and about 16,000 students. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Gallimathias Musicum For the 2018/19 academic year, CTU of- fers its students 169 study programmes Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and 480 fields of study within these pro- The Nutcracker grammes. CTU educates modern spe- cialists, scientists and managers with Francois Doppler knowledge of foreign languages, who are Andante and Rondo dynamic, flexible and able to adapt rap- idly to the requirements of the market. Bedřich Smetana Waltz No. 1 CTU currently occupies the following po- sitions according to QS World University Antonín Dvořák Rankings, which evaluated more than Biblical Songs No. -

Drottningholms Slottsteater 2014 English

drottningholms slottsteater 2014 English Opera! Esprit! Concerts! Guided tours! For young ones! Bar and picnic! WELCOME! Drottningholms Slottsteater invites you to a new and exciting season full of riches. Our wonderful theatre is absolutely unique in the world and has a story all of its own. Here, between stage and auditorium, new and different emotions are born every evening. Maestro Mozart, constantly fascinating as a composer and storyteller, is the source of our inspiration for this summer’s programme. Artistic brilliance and a will to communicate with his audience are strong ingredients both among Mozart’s talents and this summer’s productions. We wish to inspire you, our audience, to discover new works and encounter the kind of artistic expression which calls forth emotions, tells important stories. We are proud to present Mozart’s Mitridate, now fully staged in Sweden for the very first time, here with a fantastic star-studded ensemble including Miah Persson in one of the leading roles. An internationally strong artistic team, led by director Francisco Negrin, will create an elegant, different and beautiful performance. The story of the fall of a dictatorial empire and the start of a new era, hopeful of possible reconciliation and budding true love, contains several of the most marvellous arias in the history of opera. This season’s Artist in Residence, David Stern, leads the Drottningholm Theatre Orchestra, and apart from conducting Mitridate he will be leading our Gala Concert with wonderful soloist Ann Hallenberg. Mozart’s opera Idomeneo will be the other work this summer, with a big production in tandem with the Royal Swedish Opera. -

CCSSA 25807 Booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1

CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 25807 Pieter Wispelwey violoncello Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer conductor Dvořák Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in b minor Op.104 Symphonic Variations for orchestra Op.78 CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 2 “Deeply communicative and highly individual performances.” New York Times “An outstanding cellist and a really wonderful musician” Gramophone “An agile technique and complete engagement with the music” New York Times CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 3 Pieter Wispelwey is among the first of a generation of performers who are equally at ease on the modern or the period cello. His acute stylistic awareness, combined with a truly original inter- pretation and a phenomenal technical mastery, has won the hearts of critics and public alike in repertoire ranging from JS Bach to Elliott Carter. Born in Haarlem, Netherlands, Wispelwey’s sophisticated musical personality is rooted in the training he received: from early years with Dicky Boeke and Anner Bylsma in Amsterdam to Paul Katz in the USA and William Pleeth in Great Britain. In 1992 he became the first cellist ever to receive the Netherlands Music Prize, which is awarded to the most promising young musician in the Netherlands. Highlights among future concerto performances include return engagements with the Rotterdam Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Dublin National Symphony, Copenhagen Philharmonic, Sinfonietta Cracovia, debuts with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Bordeaux National Orchestra, Strasbourg Philharmonic, Tokyo Symphony and Sapporo Symphony, as well as extensive touring in the Netherlands with the BBC Scotish Symphony and across Europe with the Basel Kammer- orchester to mark Haydn’s anniversary in 2009. -

Trinity Episcopal Church Choir Invited to Perform Handel's Messiah at Carnegie Hall in New York City

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Trinity Episcopal Church Choir Invited to Perform Handel’s Messiah at Carnegie Hall in New York City New York, N.Y. – November 20, 2018 Outstanding music program Distinguished Concerts International New York City (DCINY) receives special invitation announced today that director Jennifer Wood and the Trinity Episcopal Church Choir have been invited to participate in a performance of Handel’s Messiah on the DCINY Concert Series in New York City. This performance in Isaac Stern Auditorium at Carnegie Hall on Sunday, December 1, 2019 is of the Thomas Beecham/Eugene Goossens’ 1959 Re-Orchestration for Full Symphony Orchestra. These outstanding musicians will join with other choristers to form the Distinguished Concerts Singers International, a choir of distinction. Conductor Dr. Jonathan Griffith will lead the performance and will serve as the clinician for the residency. Why the invitation was extended Dr. Jonathan Griffith, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for DCINY states: “The Trinity Episcopal Choir received this invitation because of the quality and high level of musicianship demonstrated by the singers. It is quite an honor just to be invited to perform in New York. These wonderful musicians not only represent a high quality of music and education, but they also become ambassadors for the entire community. This is an event of extreme pride for everybody and deserving of the community’s recognition and support.” The singers will spend 5 days and 4 nights in New York City in preparation for their concert. “The singers will spend approximately 9-10 hours in rehearsals over the 5 day residency.” says Griffith.