Ivan Fischer Mahler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra

issue 01 december 2010 News from the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra We hope that this reaches deeply to connect with the music lover in all of you, our Friends, and the Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra. We encourage you to submit your own thoughts and feedback on the BFO or Ivan Fischer’s concerts around the world. We hope that your travel plans will coincide with some of them. On behalf of the Friends of the BFO, we look forward to seeing you at one of the BFO concerts or Galas. Please help us to support the Budapest Festival Orchestra – a very special and talented group of musicians. Details on how you can contribute are on the back of this newsletter! We look forward to seeing more of you! The Friends of the program Budapest Festival Orchestra Gala January 26, 2011 Dinner 6:00 pm Concert 8:00 pm Lincoln Center, Avery Fisher Hall Stravinsky: Scherzo a la Russe This is the third gala sponsored by the Friends of Stravinsky: Tango the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and this year the Haydn : Cello Concerto in C Major program is fantastic with Maestro Ivan Fischer Miklos Perenyi, cello conducting Stravinsky and Haydn. Haydn: Symphony No. 92 The Dinner before the concert is being chaired Stravinsky: Suite from “The Firebird” this year by Daisy M. Soros and Cynthia M. Whitehead. Nicola Bulgari is the Honorary Single Sponsor ticket Patron Table of ten $1,000 each $10,000 Chairman. Buy your tickets now! Send in the Single Patron ticket Benefactor Table of ten enclosed envelope today! $1,500 each $15,000 A Greeting From Ivan Fischer music director of the bfo It is hard to believe that 27 years have passed since I brought into reality a personal dream, the founding of a top-level symphony orchestra in Budapest. -

Ivan Fischer Interview: Budapest Festival Orchestra and His Revolutionary Way with Opera the Conductor Is Turning Opera on Its Head with His Bold and Joyous Attitude

MENU CLASSICAL Ivan Fischer interview: Budapest Festival Orchestra and his revolutionary way with opera The conductor is turning opera on its head with his bold and joyous attitude. And the crowds are loving it Bryan Appleyard ‘There is something about being close to each other’: from left, Yvonne Naef, Sylvia Schwartz, Eva Mei, Laura Polverelli, Ivan Fischer and the BFO in Falstaff JUDIT HORVATH The Sunday Times, November 4 2018, 12:01am Share Save t’s Verdi, an aria from The Sicilian Vespers. The orchestra is playing, the soprano is singing. Then, without warning, all I the players stand up and sing the chorus. The audience gasps. The next night, it’s Verdi’s opera Falsta, and this time the audience just keeps gasping. The characters intertwine and react with the orchestra. They argue with the conductor, who grins and tut-tuts and, when Falsta hits rock bottom, gives him a cloth and a cup of wine. All of which would be amazing enough. But there is also the MENU thrilling fact that Falsta was Verdi’s last opera, and I am watching it in the last building of Andrea Palladio, arguably the greatest and certainly the most influential architect who ever lived. This first Vicenza Opera Festival at the Teatro Olimpico consists of two performances of Falsta and a gala concert. The conductor Ivan Fischer created the shows and brought his Budapest Festival Orchestra, which he set up in 1983 as an annual-festival institution. It became a permanent orchestra in 1992, but he kept the word “festival” in the title. -

Ivan Fischer

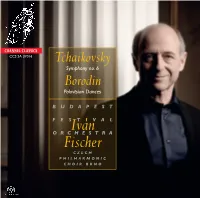

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 37016 Tchaikovsky Symphony no. 6 Borodin Polovtsian Dances BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer CZECH PHILHARMONIC CHOIR BRNO Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is the founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, as well as the IMusic Director of the Konzerthaus and Konzerthausorchester Berlin. In recent years he has also gained a reputation as a composer, with his works being performed in the United States, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Germany and Austria. What is more, he has directed a number of successful opera productions. The BFO’s frequent worldwide tours and a series of critically acclaimed and fast selling records, released first by Philips Classics and later by Channel Classics, have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most high-profile music directors. Fischer has guest-conducted the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times; every year he spends two weeks with Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; and as a conductor, he is also a frequent guest of the leading US symphonic orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra. As Music Director, he has led the Kent Opera and the Opéra National de Lyon, and was Principal Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC. Many of his recordings have been awarded prestigious international prizes. He studied piano, violin, and later the cello and composition in Budapest, before continuing his education in Vienna where he studied Conducting under Hans Swarowsky. Iván Fischer is a founder of the Hungarian Mahler Society and Patron of the British Kodály Academy. -

Ivan Fischer

CCSSA31111Booklet 21-03-2011 13:34 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 31111 Schubert Symphony no. 9 (‘Great’) in C major Five German Dances BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer CCSSA31111Booklet 21-03-2011 13:34 Pagina 2 Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra and Principal Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington D.C. He has been Iappointed Principal Conductor of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin starting the season 2012/13. The partnership between Iván Fischer and his Budapest Festival Orchestra has proved to be one of the greatest success stories in the past 25 years of classical music. Fischer introduced several reforms, developed intense rehearsal methods for the musicians, emphasizing chamber music and creative work for each orchestra member. Intense international touring and a series of acclaimed recordings for Philips Classics, later for Channel Classics have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most visionary and successful orchestra leaders. He has developed and introduced new types of concerts, ‘cocoa-concerts’ for young children, ‘surprise’ concerts where the programme is not announced, ‘one forint concerts’ where he talks to the audience, open-air concerts in Budapest attracting tens of thousands of people, as well as concert opera performances applying scenic elements. He has founded several festivals, including a summer festival in Budapest on baroque music and the Budapest Mahlerfest which is also a forum for commissioning and presenting new compositions. As a guest conductor Fischer works with the finest symphony orchestras of the world. He has been invited to the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times and he performs with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra two weeks a year. -

Trinity College Chapel Cambridge, Uk

THE CZECH TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC ORCHESTRA TRINITY COLLEGE CHAPEL CAMBRIDGE, UK THE CONCERT IS HELD UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF MR. LIBOR SEČKA, CZECH AMBASSADOR TO THE UK, MS DENISE WADDINGHAM, THE DIRECTOR OF BRITISH COUNCIL CZECH REPUBLIC, AND MR. GUY ROBERTS, THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE PRAGUE SHAKESPEARE COMPANY BY KIND PERMISSION OF THE MASTER AND FELLOWS OF TRINITY COLLEGE. THE CZECH TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY CONCERT IN PRAGUE (CTU) PROGRAMME is one of the biggest and oldest technical The concert will be introduced by Vojtěch universities in Europe. It was founded on Petráček, rector of the Czech Technical the initiative of Josef Christian Willenberg University in Prague and Nick Kingsbury, on the basis of a decree issued by Emper- Professor of Signal Processing of the Uni- or Josef I. on January 18th, 1707. versity of Cambridge, Dept of Engineering. CTU currently has eight faculties (Civil En- Jean-Joseph Mouret gineering, Mechanical Engineering, Elec- Fanfares trical Engineering, Nuclear Science and Physical Engineering, Architecture, Trans- Jan Dismas Zelenka portation Sciences, Biomedical Engineer- Salve Regina ing, Information Technology) and about 16,000 students. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Gallimathias Musicum For the 2018/19 academic year, CTU of- fers its students 169 study programmes Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and 480 fields of study within these pro- The Nutcracker grammes. CTU educates modern spe- cialists, scientists and managers with Francois Doppler knowledge of foreign languages, who are Andante and Rondo dynamic, flexible and able to adapt rap- idly to the requirements of the market. Bedřich Smetana Waltz No. 1 CTU currently occupies the following po- sitions according to QS World University Antonín Dvořák Rankings, which evaluated more than Biblical Songs No. -

CCSSA 25807 Booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1

CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 25807 Pieter Wispelwey violoncello Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer conductor Dvořák Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in b minor Op.104 Symphonic Variations for orchestra Op.78 CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 2 “Deeply communicative and highly individual performances.” New York Times “An outstanding cellist and a really wonderful musician” Gramophone “An agile technique and complete engagement with the music” New York Times CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 3 Pieter Wispelwey is among the first of a generation of performers who are equally at ease on the modern or the period cello. His acute stylistic awareness, combined with a truly original inter- pretation and a phenomenal technical mastery, has won the hearts of critics and public alike in repertoire ranging from JS Bach to Elliott Carter. Born in Haarlem, Netherlands, Wispelwey’s sophisticated musical personality is rooted in the training he received: from early years with Dicky Boeke and Anner Bylsma in Amsterdam to Paul Katz in the USA and William Pleeth in Great Britain. In 1992 he became the first cellist ever to receive the Netherlands Music Prize, which is awarded to the most promising young musician in the Netherlands. Highlights among future concerto performances include return engagements with the Rotterdam Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Dublin National Symphony, Copenhagen Philharmonic, Sinfonietta Cracovia, debuts with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Bordeaux National Orchestra, Strasbourg Philharmonic, Tokyo Symphony and Sapporo Symphony, as well as extensive touring in the Netherlands with the BBC Scotish Symphony and across Europe with the Basel Kammer- orchester to mark Haydn’s anniversary in 2009. -

Holiday Classics: Nutcracker Sweet 2018-19 Hal & Jeanette Segerstrom Family Foundation Classical Series

HOLIDAY CLASSICS: NUTCRACKER SWEET 2018-19 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES Pacifi c Symphony Brahms PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 Carl St.Clair, conductor Allegro non troppo Markus Groh, piano Allegro appassionato Andante Allegretto grazioso Markus Groh Vaughan Williams FANTASIA ON A THEME BY THOMAS TALLIS Intermission Tchaikovsky SELECTIONS FROM TCHAIKOVSKY’S THE NUTCRACKER AND ARRANGEMENTS OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S MUSIC BY DUKE ELLINGTON AND BILLY STRAYHORN Overture – Original & Ellington/Strayhorn Versions March of the Toy Soldiers – Original Sugar Rum Cherry – Ellington/Strayhorn Trepak (Russian Dance) – Original Volga Vouty ‑ Ellington/Strayhorn Coffee (Arabian Dance) – Original Tea (Chinese Dance) – Original Toot Toot Tootie Toot – Ellington/Strayhorn Dance of the Reed Flutes – Original The Waltz of the Flowers/Dance of the Floreadores – Original & Ellington/Strayhorn Preview talk with Alan Chapman at 7 p.m. Thursday, December 6, 2018 @ 8 p.m. Friday, December 7, 2018 @ 8 p.m. Saturday, December 8, 2018 @ 8 p.m. Segerstrom Center for the Arts This performance is generously sponsored by the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall Michelle F. Rohé Distinguished Pianists Fund. Offi cial Hotel Offi cial TV Station Offi cial Classical Music Station This concert is being recorded for broadcast on Sunday, Feb. 24, 2019, at 7 p.m. on Classical KUSC. 1 PROGRAM NOTES JOHANNES BRAHMS: with immediate success. PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 This concerto is a work of virtuosic demands but not of virtuosic display. One RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: When Brahms began formidable challenge for the soloist lies in FANTASIA ON A THEME BY sketching themes for his its four-movement form: not just a test of THOMAS TALLIS Piano Concerto No. -

Proms Mania: the 12 Concerts You Can't Afford to Miss

Proms mania: The 12 concerts you can't afford to miss The Proms begin next Friday with Stars, Night, Music, and Light, an apt opening for two months of imagination and grand vision. Jessica Duchen welcomes the festival and selects her highlights Friday, 8 July 2011 Flying the flag: Conductor Jiri Belohlavek conducts the orchestra during last year's Last Night of the Proms It's high summer, and the title of the first piece in the 2011 BBC Promenade Concerts says it all. Stars, Night, Music and Light is a new work commissioned for the occasion from Judith Weir – and it's a perfect launch- pad for a glittering musical celebration on a grand scale. From next Friday until mid-September, the Royal Albert Hall is home to this legendary festival. With the seats ripped out of the stalls, the Proms pack in standing listeners for the grand sum of £5 per ticket. Simply queue for places on the day and, if you arrive early enough you can be just metres away from the world's finest classical musicians while they do their stuff. Since 1895, when the conductor Sir Henry Wood founded the series, the Proms have been based on the admirable ideal of offering the highest-quality music to the widest possible audience. Today the egalitarian nature of "Promming" combines with broadcast on the radio of every concert; many are also on television, with a prime-time spot on BBC2 on Saturday nights. Satellite venues at Cadogan Hall and the Royal College of Music host lunchtime chamber-music Proms, pre-concert talks, literary events and more. -

Mahler Benjamin Zander

Mahler Benjamin Zander Symphony No. 2 ‘Resurrection’ Philharmonia Orchestra Philharmonia Chorus · Miah Persson soprano · Sarah Connolly mezzo-soprano Mahler Symphony No. 2 ‘Resurrection’ Benjamin Zander Philharmonia Orchestra Recorded at Recording editing by Watford Colosseum, London, UK Thomas C. Moore, from 6 – 8 Jan 2012 Five/Four Productions, Ltd. Produced by Post-production by Elaine Martone and Gus Skinas, Super Audio Center David St. George Design by Engineered by gmtoucari.com Robert Friedrich, Cover image by Five/Four Productions, Ltd. Tony Rinaldo Assistant engineering by All other photos of Jonathan Stokes and Neil Hutchison, Benjamin Zander by Classic Sound, Ltd. Jesse Weiner David St. George has been involved in every aspect of this recording, as co-producer and most importantly as my musical collaborator, in a relationship of deep trust and mutual understanding, in which he has guided and inspired the music at every moment. Ben Zander Symphony No. 2 in C minor ‘Resurrection’ 1. I. Allegro maestoso 22:40 2. II. Andante moderato 10:01 3. III. In ruhig fliessender Bewegung 12:44 4. IV. Urlicht 5:47 5. V. Im Tempo des Scherzo 38:57 Total Time: 90:09 Off-stage brass conductor: Courtney Lewis Be sure to visit www.linnrecords.com/mahlerdiscussion for an extensive discussion by Benjamin Zander of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, as well as other ancillary material available as free downloads. Gustav Mahler, photographed in 1892. GUSTAV MAHLER Symphony No. 2 in C minor (‘Resurrection’) Mahler began work on his Second Symphony when he was twenty-seven, still a young man. Yet the questions it raises and the solution it offers are not those of youth, but of maturity. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 129, 2009-2010

HH HI^^^HHH^^^^HHH wrYWTiV HI^B^HKftM^MUm James __ Bernard Haitink Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa iMusit^liefetor Laureate Silk twill scarves. Boston 320 Boylston Street (617) 482-8707 Hermes.com HERMES PARIS & ^ERMES, UFE AS A ^ r H ^K.r j'p.y _ nHHffinnnnMM Table of Contents | Week 23 15 BSO NEWS 23 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 25 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 28 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 30 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAM Notes on the Program 35 Gyorgy Ligeti 43 Dmitri Shostakovich 51 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 59 To Read and Hear More.. Guest Artists 65 Julian Kuerti 67 Marc-Andre Hamelin 70 SPONSORS AND DONORS 72 FUTURE PROGRAMS 74 SYMPHONY HALL EXIT PLAN 75 SYMPHONY HALL INFORMATION THIS WEEK S PRE-CONCERT TALKS ARE GIVEN BY HARLOW ROBINSON OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY. program copyright ©2010 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photograph by Michael J. Lutch BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617) 266-1492 bso.org I O N -«>»4| air-3* It's at the heart of their performance. And ours. Each musician reads from the same score, but each brings his or her own artistry to the performance. It's their passion that creates much of what we love about music. And it's what inspires all we do at Bose. That's why we're proud to support the performers you're listening to today. We invite you to experience what our passion brings to the performance of our products. Please call or visit our website to learn more- including how you can hear Bose® sound for yourself. -

Ivan Fischer

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 34213 Mahler Symphony no. 5 BUDAPEST FESTIvanI VAL ORCHESTRA Fischer Iván Fischer & Budapest Festival Orchestra ván Fischer is founder and Music Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra. This partnership Ihas become one of the greatest success stories in the past 25 years of classical music. Intense international touring and a series of acclaimed recordings for Philips Classics, later for Channel Classics have contributed to Iván Fischer’s reputation as one of the world’s most visionary and successful orchestra leaders. He has developed and introduced new types of concerts, ‘cocoa-concerts’ for young children, ‘surprise’ concerts where the programme is not announced, ‘one forint concerts’ where he talks to the audience, open-air concerts in Budapest attracting tens of thousands of people, and he staged successful opera performances. He has founded several festivals, including a summer festival in Budapest on baroque music and the Budapest Mahlerfest which is also a forum for commissioning and presenting new compositions. As a guest conductor Fischer works with the finest symphony orchestras of the world. He has been invited to the Berlin Philharmonic more than ten times, he leads every year two weeks of programs with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and appears with leading us symphony orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra. Earlier music director of Kent Opera and Lyon Opera, Principal Conductor of National Symphony Orchestra in Washington dc, his numerous recordings have won several prestigious international prizes. Iván Fischer studied piano, violin, cello and composition in Budapest, continuing his education in Vienna in Professor Hans Swarowsky’s conducting class. -

Programme Information

Programme information Saturday 24 March to Friday 30 March 2018 WEEK 13 Photo credit: Matt Crossick BLOWERS AROUND BRITAIN with HENRY BLOFELD Friday 30 March, 9pm to 10pm Tonight, Henry Blofeld (above) joins Classic FM to present a new radio series, celebrating the wealth of great classical music composed within and written about the British Isles. For the next four evenings, Blowers Around Britain will explore all corners of the British Isles, shining the spotlight on well-known and less familiar music, interspersed with stories behind the works and Blowers’ own recollections of what makes Britain great. Classic FM is available across the UK on 100-102 FM, DAB digital radio and TV, at ClassicFM.com and on the Classic FM app. 1 WEEK 13 SATURDAY 24 MARCH 5pm to 7pm: SATURDAY NIGHT AT THE MOVIES with ANDREW COLLINS Andrew Collins welcomes suggestions for show themes from Classic FM listeners – and this week, he’s been challenged by Dave in Bedfordshire to select lesser-played music by famous composers. Big names like John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, Danny Elfman and Alexandre Desplat will all make an appearance, but not with scores that have been played on the show before. 7pm to 9pm: COWAN’S CLASSICS with ROB COWAN Rob Cowan delves into his record collection to select two hours of hand-picked recordings, and this week he’ll feature music by Philip Glass, Cole Porter and Camille Saint-Saens. Rob’s Artist of the Week is the Amadeus Quartet, while Dvorak’s Symphony No.9 is the springboard for another trip to the New World in Beyond the Hall of Fame.