Cutaneous Hyperpigmentation Due to Chronic Quinine Ingestion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dermatology Eponyms – Sign –Lexicon (P)

2XU'HUPDWRORJ\2QOLQH Historical Article Dermatology Eponyms – sign –Lexicon (P)� Part 2 Piotr Brzezin´ ski1,2, Masaru Tanaka3, Husein Husein-ElAhmed4, Marco Castori5, Fatou Barro/Traoré6, Satish Kashiram Punshi7, Anca Chiriac8,9 1Department of Dermatology, 6th Military Support Unit, Ustka, Poland, 2Institute of Biology and Environmental Protection, Department of Cosmetology, Pomeranian Academy, Slupsk, Poland, 3Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University Medical Center East, Tokyo, Japan, 4Department of Dermatology, San Cecilio University Hospital, Granada, Spain, 5Medical Genetics, Department of Experimental Medicine, Sapienza - University of Rome, San Camillo-Forlanini Hospital, Rome, Italy, 6Department of Dermatology-Venerology, Yalgado Ouédraogo Teaching Hospital Center (CHU-YO), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 7Consultant in Skin Dieseases, VD, Leprosy & Leucoderma, Rajkamal Chowk, Amravati – 444 601, India, 8Department of Dermatology, Nicolina Medical Center, Iasi, Romania, 9Department of Dermato-Physiology, Apollonia University Iasi, Strada Muzicii nr 2, Iasi-700399, Romania Corresponding author: Piotr Brzezin′ski, MD PhD, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Eponyms are used almost daily in the clinical practice of dermatology. And yet, information about the person behind the eponyms is difficult to find. Indeed, who is? What is this person’s nationality? Is this person alive or dead? How can one find the paper in which this person first described the disease? Eponyms are used to describe not only disease, but also clinical signs, surgical procedures, staining techniques, pharmacological formulations, and even pieces of equipment. In this article we present the symptoms starting with (P) and other. The symptoms and their synonyms, and those who have described this symptom or phenomenon. Key words: Eponyms; Skin diseases; Sign; Phenomenon Port-Light Nose sign or tylosis palmoplantaris is widely related with the onset of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. -

Guide to Policy & Practice Questions

OREGON BOARD OF CHIROPRACTIC EXAMINERS GUIDE TO POLICY & PRACTICE QUESTIONS 530 Center St NE, suite 620 Salem, OR 97301 (503) 378-5816 [email protected] Updated/Adopted: 9/17/2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 DEVICES, PROCEDURES, AND SUBSTANCES ............................................................................................................................... 6 DEVICES ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 BAX 3000 AND SIMILAR DEVICES................................................................................................................................................ 6 BIOPTRON LIGHT THERAPY ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 CPAP MACHINE, ORDERING ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 CTD MARK I MULTI-TORSION TRACTION DEVICE................................................................................................................... 6 DYNATRON 2000 ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Clinicopathological Correlation of Acquired Hyperpigmentary Disorders

Symposium Clinicopathological correlation of acquired Dermatopathology hyperpigmentary disorders Anisha B. Patel, Raj Kubba1, Asha Kubba1 Department of Dermatology, ABSTRACT Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, Oregon, Acquired pigmentary disorders are group of heterogenous entities that share single, most USA, 1Delhi Dermatology Group, Delhi Dermpath significant, clinical feature, that is, dyspigmentation. Asians and Indians, in particular, are mostly Laboratory, New Delhi, India affected. Although the classic morphologies and common treatment options of these conditions have been reviewed in the global dermatology literature, the value of histpathological evaluation Address for correspondence: has not been thoroughly explored. The importance of accurate diagnosis is emphasized here as Dr. Asha Kubba, the underlying diseases have varying etiologies that need to be addressed in order to effectively 10, Aradhana Enclave, treat the dyspigmentation. In this review, we describe and discuss the utility of histology in the R.K. Puram, Sector‑13, diagnostic work of hyperpigmentary disorders, and how, in many cases, it can lead to targeted New Delhi ‑ 110 066, India. E‑mail: and more effective therapy. We focus on the most common acquired pigmentary disorders [email protected] seen in Indian patients as well as a few uncommon diseases with distinctive histological traits. Facial melanoses, including mimickers of melasma, are thoroughly explored. These diseases include lichen planus pigmentosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, drug‑induced melanoses, hyperpigmentation due to exogenous substances, acanthosis nigricans, and macular amyloidosis. Key words: Facial melanoses, histology of hyperpigmentary disorders and melasma, pigmentary disorders INTRODUCTION focus on the most common acquired hyperpigmentary disorders seen in Indian patients as well as a few Acquired pigmentary disorders are found all over the uncommon diseases with distinctive histological traits. -

Incontinentia Pigmenti

Incontinentia Pigmenti Authors: Prof Nikolaos G. Stavrianeas1,2, Dr Michael E. Kakepis Creation date: April 2004 1Member of The European Editorial Committee of Orphanet Encyclopedia 2Department of Dermatology and Venereology, A. Sygros Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece. [email protected] Abstract Keywords Definition Epidemiology Etiology Clinical features Course and prognosis Pathology Differential diagnosis Antenatal diagnosis Treatment References Abstract Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is an X-linked dominant single-gene disorder of skin pigmentation with neurologic, ophthalmologic, and dental involvement. IP is characterized by abnormalities of the tissues and organs derived from the ectoderm and mesoderm. The locus for IP is genetically linked to the factor VIII gene on chromosome band Xq28. Mutations in NEMO/IKK-y, which encodes a critical component of the nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) signaling pathway, are responsible for IP. IP is a rare disease (about 700 cases reported) with a worldwide distribution, more common among white patients. Characteristic skin lesions are usually present at birth in approximately 90% of patients, or they develop in early infancy. The skin changes evolve in 4 stages in a fixed chronological order. Skin, hair, nails, dental abnormalities, seizures, developmental delay, mental retardation, ataxia, spastic abnormalities, microcephaly, cerebral atrophy, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, periventricular cerebral edema may occur in more than 50% of reported cases. Ocular defects, atrophic patchy alopecia, dwarfism, clubfoot, spina bifida, hemiatrophy, and congenital hip dislocation, are reported. Treatment of cutaneous lesions is usually not required. Standard wound care should be provided in case of inflammation. Regular dental care is necessary. Pediatric ophthalmologist or retinal specialist consultations are essential. -

Covid-19 and Ectodermal Dysplasia Article

COVID-19 and ectodermal dysplasias. Recommendations are necessary. Michele Callea: Unit of Dentistry, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, IRCCS, Rome, Italy [email protected] Colin Eric Willoughby: Ulster University and Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, NI, UK [email protected] Diana Perry: UK Ectodermal Dysplasia Society President [email protected] Ulrike Holzer: Leader of EDIN Ectodermal Dysplasia International Network. Austria [email protected] Giulia Fedele: Presidente ANDE, Associazione Nazionale Displasia Ectodermica. Italy [email protected] Antonio Cárdenas Tadich: Pediatrics Service, Regional Hospital of Antofagasta, Chile [email protected] Francisco Cammarata-Scalisi: Pediatrics Service, Regional Hospital of Antofagasta, Chile [email protected] Conflict of interest: None Running title: COVID-19 and ectodermal dysplasias Sources of support if any: None Disclaimer: “We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, that the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and that each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work” Corresponding author: This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record.This Please article cite this is protected article as doi:by copyright. 10.1111/dth.13702 All rights reserved. Francisco Cammarata-Scalisi: -

Multi-Organ Teratogenesis Sequels of Bigger Size Particles Colloidal

ytology & f C H o is Prakash, et al., J Cytol Histol 2018, 9:2 l t a o n l o r DOI: 10.4172/2157-7099.1000501 g u y o J Journal of Cytology & Histology ISSN: 2157-7099 Research Article Open Access Multi-Organ Teratogenesis Sequels of Bigger Size Particles Colloidal Silver in Primate Vertebrates Pani Jyoti Prakash*1, Singh Royana2 and Pani Sankarsan3 1Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Medical Science and Research, Karjat, Bhivpuri, India 2Department of Anatomy, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttarpradesh, India 3Deapartment of Surgery, Institute of Medical Science and Research, Karjat, Bhivpuri, India *Corresponding author: Prakash PJ, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Medical Science and Research, Karjat, Bhivpuri, India, Tel: 8433668356; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 21, 2018; Accepted date: March 12, 2018; Published date: March 16, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Prakash PJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Back ground: In this most recent, update global arena for consumers products most of the daily applications of bigger silver nano particles (20 to 100 nano meter range) are effected as anti-viral and anti-parasitic agents in clinical medicine and diagnosis which is a positive feedback. However, the major negative feedback of bigger size silver nano particles on human, animal and primate vertebrate body is multisystem teratogenicity focuses. Material and methods: This study was designed to investigate teratogenic effects of bigger size nano silver which is poly vinyl pyrollidone coated and sodium borohydride stabilized. -

A Case of Argyria: Multiple Forms of Silver Ingestion in a Patient with Comorbid Schizoaffective Disorder

A Case of Argyria: Multiple Forms of Silver Ingestion in a Patient With Comorbid Schizoaffective Disorder Sarah J. Schrauben, MD; Dhaval G. Bhanusali, MD; Stuart Sheets, MD; Animesh A. Sinha, MD, PhD Argyria is a rare cutaneous manifestation of silver is an elemental compound often found in drinking deposits in the skin, characterized by a grayish water, various sources in industry, and alternative blue discoloration, particularly in sun-exposed medicine compounds. Silver was first used medically areas. We report the case of a patient with a his- in 980 ad; it was believed to provide a means of tory of schizoaffective disorder and type 2 diabe- blood purification, to treat heart palpitations, and to tes mellitus who presented with argyria of the face serve as an adjunct treatment of epilepsy and tabes and neck. The patient had a history of ingesting dorsalis.1 In the 1900s, silver began being used as a colloidal silver proteins (CSPs) for approximately popular treatment of infections. However, reports of 10 years as a self-prescribed remedy for his medi- unsolicited side effects diminished its popularity as a cal conditions. CUTISmainstay solution for many ailments. Silver recently Colloidal silver protein has gained popularity has regained popularity, with an increase in Internet among patients who seek alternative medical ther- claims promoting the use of oral colloidal silver pro- apies. Argyria is the most predominant manifesta- teins (CSPs) as mineral supplements and as a way to tion of silver toxicity. It is unclear if our patient prevent and treat many diseases.2 began taking CSP becauseDo of his schizoaffectiveNot WeCopy present a patient with argyria as a conse- disorder or if silver toxicity may have induced quence of multiple forms of silver ingestion in an somatic delusions; however, it is important for attempt to treat his type 2 diabetes mellitus and physicians to have a thorough understanding of schizoaffective disorder. -

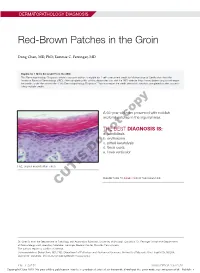

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

Level I Syllabus

LEVEL I SYLLABUS 1 ACDT Course Learning Objectives Upon Completion, Those Enrolled Will Be MODULE Prepared To... The Language of Dermatology 1. Define and spell the following cutaneous lesions/descriptors: a. Macule b. Patch c. Papule d. Nodule e. Cyst f. Plaque g. Wheal h. Vesicle i. Bulla j. Pustule k. Erosion l. Ulcer m. Atrophy n. Scaling o. Crusting p. Excoriations q. Fissures r. Lichenification s. Erythematous t. Violaceous u. Purpuric v. Hypo/Hyperpigmented w. Linear x. Annular y. Nummular/Discoid z. Blaschkoid aa. Morbilliform bb. Polycyclic cc. Arcuate dd. Reticular Collecting & Documenting Patient History Part I 1. Describe the importance of documentation and chart review, while properly collecting dermatologyspecific medical history components, including: a. Chief Complaint b. Past Medical History c. Family History d. Medications e. Allergies Collecting & Documenting Patient History Part II 1. Demonstrate the proper collection of dermatologyspecific medical history and explain the significance of the following: a. Social History b. Review of Systems c. History of Present Illness Anatomy 1. Spell and document the following directional indicators while applying them to the appropriate anatomical landmarks: a. Proximal/Distal b. Superior/Mid/Inferior c. Anterior/Posterior d. Medial/Lateral e. Dorsal/Ventral 2. Spell and identify specific anatomical locations involving the: a. Scalp b. Forehead c. Ears d. Eyes e. Nose f. Cheeks g. Lips h. Chin i. Neck j. Back k. Upper extremity l. Hands m. Nails n. Chest o. Abdomen p. Buttocks q. Hips r. Lower extremity s. Feet Skin Structure and Function 1. Identify and spell the three primary layers of skin: a. -

Pigmented Contact Dermatitis and Chemical Depigmentation

18_319_334* 05.11.2005 10:30 Uhr Seite 319 Chapter 18 Pigmented Contact Dermatitis 18 and Chemical Depigmentation Hideo Nakayama Contents ca, often occurs without showing any positive mani- 18.1 Hyperpigmentation Associated festations of dermatitis such as marked erythema, with Contact Dermatitis . 319 vesiculation, swelling, papules, rough skin or scaling. 18.1.1 Classification . 319 Therefore, patients may complain only of a pigmen- 18.1.2 Pigmented Contact Dermatitis . 320 tary disorder, even though the disease is entirely the 18.1.2.1 History and Causative Agents . 320 result of allergic contact dermatitis. Hyperpigmenta- 18.1.2.2 Differential Diagnosis . 323 tion caused by incontinentia pigmenti histologica 18.1.2.3 Prevention and Treatment . 323 has often been called a lichenoid reaction, since the 18.1.3 Pigmented Cosmetic Dermatitis . 324 presence of basal liquefaction degeneration, the ac- 18.1.3.1 Signs . 324 cumulation of melanin pigment, and the mononucle- 18.1.3.2 Causative Allergens . 325 ar cell infiltrate in the upper dermis are very similar 18.1.3.3 Treatment . 326 to the histopathological manifestations of lichen pla- 18.1.4 Purpuric Dermatitis . 328 nus. However, compared with typical lichen planus, 18.1.5 “Dirty Neck” of Atopic Eczema . 329 hyperkeratosis is usually milder, hypergranulosis 18.2 Depigmentation from Contact and saw-tooth-shape acanthosis are lacking, hyaline with Chemicals . 330 bodies are hardly seen, and the band-like massive in- 18.2.1 Mechanism of Leukoderma filtration with lymphocytes and histiocytes is lack- due to Chemicals . 330 ing. 18.2.2 Contact Leukoderma Caused Mainly by Contact Sensitization . -

Urticaria and Angioedema

Challenging Cases in Allergy and Immunology Massoud Mahmoudi Editor Challenging Cases in Allergy and Immunology Editor Massoud Mahmoudi D.O, Ph.D. RM (NRM), FACOI, FAOCAI, FASCMS, FACP, FCCP, FAAAAI Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine University of California San Francisco San Francisco, California Chairman, Department of Medicine Community Hospital of Los Gatos Los Gatos, California USA ISBN 978-1-60327-442-5 e-ISBN 978-1-60327-443-2 DOI 10.1007/978-1-60327-443-2 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009928233 © Humana Press, a part of Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Humana Press, c/o Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. -

X-Linked Diseases: Susceptible Females

REVIEW ARTICLE X-linked diseases: susceptible females Barbara R. Migeon, MD 1 The role of X-inactivation is often ignored as a prime cause of sex data include reasons why women are often protected from the differences in disease. Yet, the way males and females express their deleterious variants carried on their X chromosome, and the factors X-linked genes has a major role in the dissimilar phenotypes that that render women susceptible in some instances. underlie many rare and common disorders, such as intellectual deficiency, epilepsy, congenital abnormalities, and diseases of the Genetics in Medicine (2020) 22:1156–1174; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436- heart, blood, skin, muscle, and bones. Summarized here are many 020-0779-4 examples of the different presentations in males and females. Other INTRODUCTION SEX DIFFERENCES ARE DUE TO X-INACTIVATION Sex differences in human disease are usually attributed to The sex differences in the effect of X-linked pathologic variants sex specific life experiences, and sex hormones that is due to our method of X chromosome dosage compensation, influence the function of susceptible genes throughout the called X-inactivation;9 humans and most placental mammals – genome.1 5 Such factors do account for some dissimilarities. compensate for the sex difference in number of X chromosomes However, a major cause of sex-determined expression of (that is, XX females versus XY males) by transcribing only one disease has to do with differences in how males and females of the two female X chromosomes. X-inactivation silences all X transcribe their gene-rich human X chromosomes, which is chromosomes but one; therefore, both males and females have a often underappreciated as a cause of sex differences in single active X.10,11 disease.6 Males are the usual ones affected by X-linked For 46 XY males, that X is the only one they have; it always pathogenic variants.6 Females are biologically superior; a comes from their mother, as fathers contribute their Y female usually has no disease, or much less severe disease chromosome.