Clinicopathological Correlation of Acquired Hyperpigmentary Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dermatology Eponyms – Sign –Lexicon (P)

2XU'HUPDWRORJ\2QOLQH Historical Article Dermatology Eponyms – sign –Lexicon (P)� Part 2 Piotr Brzezin´ ski1,2, Masaru Tanaka3, Husein Husein-ElAhmed4, Marco Castori5, Fatou Barro/Traoré6, Satish Kashiram Punshi7, Anca Chiriac8,9 1Department of Dermatology, 6th Military Support Unit, Ustka, Poland, 2Institute of Biology and Environmental Protection, Department of Cosmetology, Pomeranian Academy, Slupsk, Poland, 3Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University Medical Center East, Tokyo, Japan, 4Department of Dermatology, San Cecilio University Hospital, Granada, Spain, 5Medical Genetics, Department of Experimental Medicine, Sapienza - University of Rome, San Camillo-Forlanini Hospital, Rome, Italy, 6Department of Dermatology-Venerology, Yalgado Ouédraogo Teaching Hospital Center (CHU-YO), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 7Consultant in Skin Dieseases, VD, Leprosy & Leucoderma, Rajkamal Chowk, Amravati – 444 601, India, 8Department of Dermatology, Nicolina Medical Center, Iasi, Romania, 9Department of Dermato-Physiology, Apollonia University Iasi, Strada Muzicii nr 2, Iasi-700399, Romania Corresponding author: Piotr Brzezin′ski, MD PhD, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Eponyms are used almost daily in the clinical practice of dermatology. And yet, information about the person behind the eponyms is difficult to find. Indeed, who is? What is this person’s nationality? Is this person alive or dead? How can one find the paper in which this person first described the disease? Eponyms are used to describe not only disease, but also clinical signs, surgical procedures, staining techniques, pharmacological formulations, and even pieces of equipment. In this article we present the symptoms starting with (P) and other. The symptoms and their synonyms, and those who have described this symptom or phenomenon. Key words: Eponyms; Skin diseases; Sign; Phenomenon Port-Light Nose sign or tylosis palmoplantaris is widely related with the onset of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. -

Guide to Policy & Practice Questions

OREGON BOARD OF CHIROPRACTIC EXAMINERS GUIDE TO POLICY & PRACTICE QUESTIONS 530 Center St NE, suite 620 Salem, OR 97301 (503) 378-5816 [email protected] Updated/Adopted: 9/17/2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 DEVICES, PROCEDURES, AND SUBSTANCES ............................................................................................................................... 6 DEVICES ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 BAX 3000 AND SIMILAR DEVICES................................................................................................................................................ 6 BIOPTRON LIGHT THERAPY ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 CPAP MACHINE, ORDERING ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 CTD MARK I MULTI-TORSION TRACTION DEVICE................................................................................................................... 6 DYNATRON 2000 ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Dermatologic Manifestations of Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome in Patients with and Without a 16–Base Pair Duplication in the HPS1 Gene

STUDY Dermatologic Manifestations of Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome in Patients With and Without a 16–Base Pair Duplication in the HPS1 Gene Jorge Toro, MD; Maria Turner, MD; William A. Gahl, MD, PhD Background: Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS) con- without the duplication were non–Puerto Rican except sists of oculocutaneous albinism, a platelet storage pool de- 4 from central Puerto Rico. ficiency, and lysosomal accumulation of ceroid lipofuscin. Patients with HPS from northwest Puerto Rico are homozy- Results: Both patients homozygous for the 16-bp du- gous for a 16–base pair (bp) duplication in exon 15 of HPS1, plication and patients without the duplication dis- a gene on chromosome 10q23 known to cause the disorder. played skin color ranging from white to light brown. Pa- tients with the duplication, as well as those lacking the Objective: To determine the dermatologic findings of duplication, had hair color ranging from white to brown patients with HPS. and eye color ranging from blue to brown. New findings in both groups of patients with HPS were melanocytic Design: Survey of inpatients with HPS by physical ex- nevi with dysplastic features, acanthosis nigricans–like amination. lesions in the axilla and neck, and trichomegaly. Eighty percent of patients with the duplication exhibited fea- Setting: National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, tures of solar damage, including multiple freckles, stel- Bethesda, Md (a tertiary referral hospital). late lentigines, actinic keratoses, and, occasionally, basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas. Only 8% of patients Patients: Sixty-five patients aged 3 to 54 years were di- lacking the 16-bp duplication displayed these findings. -

Q-Switched Laser-Induced Chrysiasis Treated with Long-Pulsed Laser

THE CUTTING EDGE SECTION EDITOR: GEORGE J. HRUZA, MD; ASSISTANT SECTION EDITORS: DEE ANNA GLASER, MD; ELAINE SIEGFRIED, MD Q-Switched Laser-Induced Chrysiasis Treated With Long-Pulsed Laser Patricia Lee Yun, MD; Kenneth A. Arndt, MD; R. Rox Anderson, MD; Wellman Laboratories of Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (Drs Yun and Anderson), Skin Care Physicians of Chestnut Hill, Chestnut Hill, Mass (Dr Arndt) The Cutting Edge: Challenges in Medical and Surgical Therapeutics REPORT OF A CASE on her cheeks and forehead ranging from 2 to 6 mm (Figure 1). The lesions did not enhance on Wood’s light A 70-year-old woman presented for elective treatment of examination, suggesting dermal pigmentation. In some lentigines on her face. This was her first treatment with areas, portions of the original lentigo were still visible in any laser. She was treated with a Q-switched alexan- the center of the blue macule. There was no discolora- drite laser (755 nm, 50 nanoseconds, 3.5 J/cm2, 15 pulses tion of the sclera, nails, or hair. A subtle blue-gray hue of 4-mm spot diameter; Candela, Wayland, Mass), caus- in the patient’s general skin color was noted at the time ing what appeared to be usual purpura immediately fol- of reexamination. lowing laser exposure of 8 tan macules. Several weeks A punch biopsy specimen of a representative area dem- later, blue-black discoloration was present, and was at- onstrated numerous black particles within macrophages tributed to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but in the dermis. A diagnosis of Q-switched laser-induced failed to lighten over the next 4 months. -

A Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals a Locus for Bilateral Iridal Hypopigmentation in Holstein Friesian Cattle Anne K

Hollmann et al. BMC Genetics (2017) 18:30 DOI 10.1186/s12863-017-0496-4 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access A genome-wide association study reveals a locus for bilateral iridal hypopigmentation in Holstein Friesian cattle Anne K. Hollmann1, Martina Bleyer2, Andrea Tipold3, Jasmin N. Neßler3, Wilhelm E. Wemheuer1, Ekkehard Schütz1 and Bertram Brenig1* Abstract Background: Eye pigmentation abnormalities in cattle are often related to albinism, Chediak-Higashi or Tietz like syndrome. However, mutations only affecting pigmentation of coat color and eye have also been described. Herein 18 Holstein Friesian cattle affected by bicolored and hypopigmented irises have been investigated. Results: Affected animals did not reveal any ophthalmological or neurological abnormalities besides the specific iris color differences. Coat color of affected cattle did not differ from controls. Histological examination revealed a reduction of melanin pigment in the iridal anterior border layer and stroma in cases as cause of iris hypopigmentation. To analyze the genetics of the iris pigmentation differences, a genome-wide association study was performed using Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip genotypes of the 18 cases and 172 randomly chosen control animals. A significant association on bovine chromosome 8 (BTA8) was identified at position 60,990,733 with a -log10(p) = 9.17. Analysis of genotypic and allelic dependences between cases of iridal hypopigmentation and an additional set of 316 randomly selected Holstein Friesian cattle controls showed that allele A at position 60,990,733 on BTA8 (P =4.0e–08, odds ratio = 6.3, 95% confidence interval 3.02–13.17) significantly increased the chance of iridal hypopigmentation. Conclusions: The clinical appearance of the iridal hypopigmentation differed from previously reported cases of pigmentation abnormalities in syndromes like Chediak-Higashi or Tietz and seems to be mainly of cosmetic character. -

Hydroxychloroquine-Associated Hyperpigmentation Mimicking Elder Abuse

Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) (2013) 3:203–210 DOI 10.1007/s13555-013-0032-z CASE REPORT Hydroxychloroquine-Associated Hyperpigmentation Mimicking Elder Abuse Philip R. Cohen To view enhanced content go to www.dermtherapy-open.com Received: June 17, 2013 / Published online: August 14, 2013 Ó The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com ABSTRACT cleared of suspected elder abuse. A skin biopsy of the patient’s dyschromia confirmed the Background: Hydroxychloroquine may result diagnosis of hydroxychloroquine-associated in cutaneous dyschromia. Older individuals hyperpigmentation. who are the victims of elder abuse can present Conclusion: Hyperpigmentation of skin, with bruising and resolving ecchymoses. mucosa, and nails can be observed in patients Purpose: The features of hydroxychloroquine- treated with antimalarials, including associated hyperpigmentation are described, hydroxychloroquine. Elder abuse is a significant the mucosal and skin manifestations of elder and underreported problem in seniors. abuse are reviewed, and the mucocutaneous Cutaneous findings can aid in the discovery of mimickers of elder abuse are summarized. physical abuse, sexual abuse, and self-neglect in Case Report: An elderly woman being treated elderly individuals. However, medication- with hydroxychloroquine for systemic lupus associated effects, systemic conditions, and erythematosus developed drug-associated black accidental external injuries can mimic elder and blue pigmentation of her skin. The abuse. Therefore, a complete medical history dyschromia was misinterpreted by her and appropriate laboratory evaluation, including clinician as elder abuse and Adult Protective skin biopsy, should be conducted when the Services was notified. The family was eventually diagnosis of elder abuse is suspected. Keywords: Abuse; Dyschromia; Elderly; P. -

Multi-Organ Teratogenesis Sequels of Bigger Size Particles Colloidal

ytology & f C H o is Prakash, et al., J Cytol Histol 2018, 9:2 l t a o n l o r DOI: 10.4172/2157-7099.1000501 g u y o J Journal of Cytology & Histology ISSN: 2157-7099 Research Article Open Access Multi-Organ Teratogenesis Sequels of Bigger Size Particles Colloidal Silver in Primate Vertebrates Pani Jyoti Prakash*1, Singh Royana2 and Pani Sankarsan3 1Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Medical Science and Research, Karjat, Bhivpuri, India 2Department of Anatomy, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttarpradesh, India 3Deapartment of Surgery, Institute of Medical Science and Research, Karjat, Bhivpuri, India *Corresponding author: Prakash PJ, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Medical Science and Research, Karjat, Bhivpuri, India, Tel: 8433668356; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 21, 2018; Accepted date: March 12, 2018; Published date: March 16, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Prakash PJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Back ground: In this most recent, update global arena for consumers products most of the daily applications of bigger silver nano particles (20 to 100 nano meter range) are effected as anti-viral and anti-parasitic agents in clinical medicine and diagnosis which is a positive feedback. However, the major negative feedback of bigger size silver nano particles on human, animal and primate vertebrate body is multisystem teratogenicity focuses. Material and methods: This study was designed to investigate teratogenic effects of bigger size nano silver which is poly vinyl pyrollidone coated and sodium borohydride stabilized. -

Ocular Chrysiasis: a Teaching Case Report | 1

Ocular Chrysiasis: a Teaching Case Report | 1 Abstract Ocular chrysiasis is a deposition of gold in ocular structures secondary to gold salt therapy, which is primarily used in infectious, rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. Gold therapy has become an extremely rare treatment due to the advent of rheumatologic medications with better safety profiles. However, any patient who has undergone gold therapy could potentially have ocular chrysiasis. Therefore, it must be included as a differential in the presence of corneal or lenticular changes in these patients. Additionally, it is important to include ocular chrysiasis as a differential in the presence of crystalline keratopathies. A detailed medical history and thorough ocular examination can assist clinicians in making a correct diagnosis. Key Words: gold salts, ocular chrysiasis, autoimmune disease, cornea Background The following case report is meant to be used as a guide in teaching optometry students and residents. It is relevant to all levels of training. Ocular chrysiasis is a deposition of gold in ocular structures following chrysotherapy, which is the medical use of gold salts. Chrysotherapy was primarily used to treat infectious, rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. This therapy has become an extremely rare treatment due to the advent of rheumatologic medications with better safety profiles. Any patient who has undergone gold therapy could potentially have ocular chrysiasis. Therefore, it must be included as a differential in the presence of corneal or lenticular changes in these patients. This case illustrates the importance of history-taking skills, examination and decision-making in effectively diagnosing this condition. Case Description A 54-year-old Caucasian female presented for an annual eye examination. -

A Case of Argyria: Multiple Forms of Silver Ingestion in a Patient with Comorbid Schizoaffective Disorder

A Case of Argyria: Multiple Forms of Silver Ingestion in a Patient With Comorbid Schizoaffective Disorder Sarah J. Schrauben, MD; Dhaval G. Bhanusali, MD; Stuart Sheets, MD; Animesh A. Sinha, MD, PhD Argyria is a rare cutaneous manifestation of silver is an elemental compound often found in drinking deposits in the skin, characterized by a grayish water, various sources in industry, and alternative blue discoloration, particularly in sun-exposed medicine compounds. Silver was first used medically areas. We report the case of a patient with a his- in 980 ad; it was believed to provide a means of tory of schizoaffective disorder and type 2 diabe- blood purification, to treat heart palpitations, and to tes mellitus who presented with argyria of the face serve as an adjunct treatment of epilepsy and tabes and neck. The patient had a history of ingesting dorsalis.1 In the 1900s, silver began being used as a colloidal silver proteins (CSPs) for approximately popular treatment of infections. However, reports of 10 years as a self-prescribed remedy for his medi- unsolicited side effects diminished its popularity as a cal conditions. CUTISmainstay solution for many ailments. Silver recently Colloidal silver protein has gained popularity has regained popularity, with an increase in Internet among patients who seek alternative medical ther- claims promoting the use of oral colloidal silver pro- apies. Argyria is the most predominant manifesta- teins (CSPs) as mineral supplements and as a way to tion of silver toxicity. It is unclear if our patient prevent and treat many diseases.2 began taking CSP becauseDo of his schizoaffectiveNot WeCopy present a patient with argyria as a conse- disorder or if silver toxicity may have induced quence of multiple forms of silver ingestion in an somatic delusions; however, it is important for attempt to treat his type 2 diabetes mellitus and physicians to have a thorough understanding of schizoaffective disorder. -

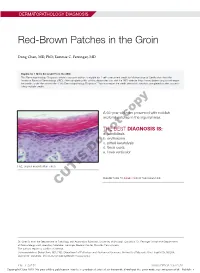

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

Pigmented Contact Dermatitis and Chemical Depigmentation

18_319_334* 05.11.2005 10:30 Uhr Seite 319 Chapter 18 Pigmented Contact Dermatitis 18 and Chemical Depigmentation Hideo Nakayama Contents ca, often occurs without showing any positive mani- 18.1 Hyperpigmentation Associated festations of dermatitis such as marked erythema, with Contact Dermatitis . 319 vesiculation, swelling, papules, rough skin or scaling. 18.1.1 Classification . 319 Therefore, patients may complain only of a pigmen- 18.1.2 Pigmented Contact Dermatitis . 320 tary disorder, even though the disease is entirely the 18.1.2.1 History and Causative Agents . 320 result of allergic contact dermatitis. Hyperpigmenta- 18.1.2.2 Differential Diagnosis . 323 tion caused by incontinentia pigmenti histologica 18.1.2.3 Prevention and Treatment . 323 has often been called a lichenoid reaction, since the 18.1.3 Pigmented Cosmetic Dermatitis . 324 presence of basal liquefaction degeneration, the ac- 18.1.3.1 Signs . 324 cumulation of melanin pigment, and the mononucle- 18.1.3.2 Causative Allergens . 325 ar cell infiltrate in the upper dermis are very similar 18.1.3.3 Treatment . 326 to the histopathological manifestations of lichen pla- 18.1.4 Purpuric Dermatitis . 328 nus. However, compared with typical lichen planus, 18.1.5 “Dirty Neck” of Atopic Eczema . 329 hyperkeratosis is usually milder, hypergranulosis 18.2 Depigmentation from Contact and saw-tooth-shape acanthosis are lacking, hyaline with Chemicals . 330 bodies are hardly seen, and the band-like massive in- 18.2.1 Mechanism of Leukoderma filtration with lymphocytes and histiocytes is lack- due to Chemicals . 330 ing. 18.2.2 Contact Leukoderma Caused Mainly by Contact Sensitization . -

Atypical Variants of Mycosis Fungoides

Altınışık et al. Atypical Variants of Mycosis Fungoides REVIEW DOI: 10.4274/jtad.galenos.2021.09719 J Turk Acad Dermatol 2021;15(2):30-33 Atypical Variants of Mycosis Fungoides Dursun Dorukhan Altınışık, Özge Aşkın, Tuğba Kevser Uzunçakmak, Burhan Engin Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine, Department of Dermatology, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and it is characterised by specific histological features. MF is in a spectrum of disorders which includes Sezary syndrome and other CTCL subtypes. Clinically and histopathologically it can imitate other T-cell mediated dermatosis hence making its diagnosis difficult. Due to different prognosis and difference in treatment strategies other subtypes of CTCL must be differentiated from MF. MF is a clinically indolent low-grade lymphoma which is seen in people aged between 55- 60 and it’s seen more commonly in men (2:1 ratio). Meanwhile other subtypes of MF like folliculotropic variant may show relatively a more aggressive course and our treatment strategy may differ. Keywords: Mycosis fungoides, Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Phototherapy, PUVA Introduction follicles frequently causing alopecia and in the paediatric population Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell it tends to accompany hypopigmented patches and plaques. FMF lymphoma (CTCL) and it is characterised by specific histological preferentially involves the head and neck region however it can features [1]. MF is in a spectrum of disorders which includes Sezary sometimes involve the trunk or the extremities [6]. Patients with syndrome and other CTCL subtypes. Clinically and histopathologically FMF have significant pruritus which may be overlapped by S.