OXFORD LECTURE 2 BREAKING the RULES Good Evening. Last

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 2:18-Mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 32

Case 2:18-mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 32 1 MCGREGOR W. SCOTT United States Attorney 2 AUDREY B. HEMESATH HEIKO P. COPPOLA 3 Assistant United States Attorneys 501 I Street, Suite 10-100 4 Sacramento, CA 95814 Telephone: (916) 554-2700 5 CHRISTOPHER J. SMITH 6 Acting Associate Director 7 JOHN D. RIESENBERG Trial Attorney 8 Office of International Affairs Criminal Division 9 U.S. Department of Justice 1301 New York Avenue NW 10 Washington, D.C. 20530 11 Telephone: (202) 514-0000 12 Attorneys for Plaintiff 13 United States of America 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 15 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 16 17 IN THE MATTER OF 18 THE EXTRADITION OF OMAR AMEEN CASE NO. 2:18-MJ-0152 EFB 19 20 21 22 MEMORANDUM OF EXTRADITION LAW AND REQUEST 23 FOR DETENTION PENDING EXTRADITION PROCEEDINGS 24 25 26 27 28 Case 2:18-mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 2 of 32 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..........................................................................................................1 3 II. LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF EXTRADITION PROCEEDINGS ...................................................2 4 A. The limited role of the Court in extradition proceedings. ....................................................2 5 B. The Requirements for Certification .....................................................................................3 6 1. Authority Over the Proceedings ...........................................................................3 7 2. Jurisdiction Over the Fugitive ..............................................................................4 -

Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g15z7t No online items Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 Finding aid prepared by Performing Arts Special Collections Staff; additions processed by Peggy Alexander; machine readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 PASC 353 1 Title: Roy Huggins papers Collection number: PASC 353 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Physical Description: 20 linear ft.(58 boxes) Date: 1948-2002 Abstract: Papers belonging to the novelist, blacklisted film and television writer, producer and production manager, Roy Huggins. The collection is in the midst of being processed. The finding aid will be updated periodically. Creator: Huggins, Roy 1914-2002 Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

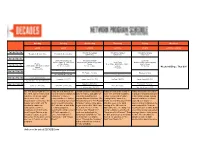

Visit Us on the Web at DECADES.Com

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Weekend 6/8/15 6/9/15 6/10/15 6/11/15 6/12/15 6/13/15 - 6/14/15 7a / 1p / 7p / 1a Through the Decades Through the Decades Through the Decades Through the Decades {CC} Through the Decades {CC} 150610 {CC} 150611 {CC} 150612 {CC} 8a / 2p / 8p / 2a Drifter: Henry Lee Lucas The Boston Strangler Love Field Antonio Sabato Jr., John Burke David Faustino, Andrew Divoff (2008) - Hanky Panky Michelle Pfeiffer, Dennis Haysbert Frances 9a / 3p / 9p / 3a (2009) - Thriller Thriller Gene Wilder, Gilda Radner (1982) - (1992) - Drama Jessica Lange, Kim Stanley (1982) - TV-14 L, S, V {CC} TV-14 L, V {CC} Comedy TV-14 {CC} Weekend Binge: That Girl Drama TV-PG {CC} TV-14 S, V {CC} Greatest Sports Legends: Secretariat 06 10a / 4p / 10p / 4a {CC} The Fugitive 153 {CC} Bonanza 527 {CC} Love, American Style 666 {CC} Disasters of the Century: Le Mans Race Car Crash 010 {CC} 11a / 5p / 11p / 5a I Love Lucy 155 {CC} Gunsmoke 7215 {CC} Hawaii Five-O 6817 {CC} The Saint 110 {CC} Daniel Boone 3007 {CC} Car 54, Where Are You? 051 {CC} 12p / 6p / 12a / 6a Naked City 0010 {CC} The Greats: Anne Frank 09 {CC} Gunsmoke 7413 {CC} Hawaii Five-O 7214 {CC} Route 66 13 {CC} The Achievers: Babe Ruth 12 {CC} Have Gun, Will Travel 118 {CC} Our look back begins on June Today we look back at the Serials kilers have an infamous Today we look at the events of Today we examine the topics 8th, 1949, with the Hollywood end of a historic manhunt for place in history, and today we June 11th. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Weekend Movie Schedule Photo Can Be Fixed

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 12, 2006 5 MONDAY EVENING MAY 15, 2006 brassiere). However, speaking as a 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 fellow sugar addict, my advice is to E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Photo can be fixed start cutting back on the sugar, be- The First 48: Twisted Tattoo Fixation Influences; Inked Inked Crossing Jordan (TV14) The First 48: Twisted 36 47 A&E DEAR ABBY: My husband, cause not only is it addictive, it also Honor; Vultures designs. (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (HD) Honor; Vultures abigail Oprah Winfrey’s Legends Grey’s Anatomy: Deterioration of the Fight or Flight KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live “Keith,” and I are eagerly awaiting makes you crave more and more. And 4 6 ABC an hour after you’ve consumed it, Ball (N) Response/Losing My Religion (N) (HD) at 10 (N) (TV14) the birth of our first child. Sadly, van buren Animal Precinct: New Be- Miami Animal Police: Miami Animal Police: Animal Precinct: New Be- Miami Animal Police: Keith’s mother is in very poor health. you’ll feel as fatigued as you felt “en- 26 54 ANPL ginnings (TV G) Gators Galore (TVPG) Gator Love Bite ginnings (TV G) Gators Galore (TVPG) ergized” immediately afterward. The West Wing: Tomor- “A Bronx Tale” (‘93, Drama) Robert De Niro. A ‘60s bus driver “A Bronx Tale” (‘93, Drama) A man She’s not expected to live more than 63 67 BRAVO a few months after the birth of her dear abby DEAR ABBY: I was adopted by a row (TVPG) (HD) struggles to bring up his son right amid temptations. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

Highway Patrol Dragnet Saved by the Bell (E/I) the Waltons the Flintstones Have Gun, Will Travel the Jetsons (Eff. 2/21) The

Daniel Boone EFFECTIVE 2/21/21 ALL TIMES EASTERN / PACIFIC MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00a Dragnet The Beverly Hillbillies 6:00a The Powers of Matthew Star 6:30a My Three Sons The Beverly Hillbillies 6:30a 7:00a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 7:00a Toon In With Me Popeye and Pals 7:30a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 7:30a 8:00a Leave It to Beaver Saved by the Bell (E/I) 8:00a The Tom and Jerry Show 8:30a Leave It to Beaver Saved by the Bell (E/I) 8:30a 9:00a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 9:00a Perry Mason Bugs Bunny and Friends 9:30a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 9:30a 10:00a The Flintstones 10:00a Matlock Maverick 10:30a The Flintstones 10:30a 11:00a The Flintstones 11:00a In the Heat of the Night Wagon Train 11:30a The Jetsons (Eff. 2/21) 11:30a 12:00p 12:00p The Waltons The Big Valley 12:30p 12:30p The Brady Bunch Brunch 1:00p 1:00p Gunsmoke Gunsmoke 1:30p 1:30p 2:00p 2:00p Bonanza Bonanza 2:30p 2:30p 3:00p The Rifleman 3:00p Rawhide Gilligan's Island Three Hour Tour 3:30p The Rifleman 3:30p 4:00p Have Gun, Will Travel 4:00p Wagon Train 4:30p Wanted: Dead or Alive 4:30p 5:00p Adam-12 The Rifleman Mama's Family 5:00p 5:30p Adam-12 The Rifleman Mama's Family 5:30p 6:00p The Flintstones 6:00p The Love Boat 6:30p Happy Days 6:30p The Three Stooges 7:00p M*A*S*H M*A*S*H 7:00p 7:30p M*A*S*H M*A*S*H 7:30p 8:00p The Andy Griffith Show 8:00p 8:30p The Andy Griffith Show Svengoolie 8:30p Columbo 9:00p Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. -

Highway Patrol Dragnet Popeye and Pals the Tom And

Daniel Boone EFFECTIVE 3/21/21 ALL TIMES EASTERN / PACIFIC MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00a Dragnet The Beverly Hillbillies 6:00a The Powers of Matthew Star 6:30a My Three Sons The Beverly Hillbillies 6:30a 7:00a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 7:00a Toon In With Me Popeye and Pals 7:30a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 7:30a 8:00a Leave It to Beaver Saved by the Bell (E/I) 8:00a The Tom and Jerry Show 8:30a Leave It to Beaver Saved by the Bell (E/I) 8:30a 9:00a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 9:00a Perry Mason Bugs Bunny and Friends 9:30a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 9:30a 10:00a The Flintstones 10:00a Matlock Maverick 10:30a The Flintstones 10:30a 11:00a The Flintstones 11:00a In the Heat of the Night Wagon Train 11:30a The Jetsons 11:30a 12:00p 12:00p The Waltons The Big Valley 12:30p 12:30p The Brady Bunch Brunch 1:00p 1:00p Gunsmoke Gunsmoke 1:30p 1:30p 2:00p 2:00p Bonanza Bonanza 2:30p 2:30p 3:00p The Rifleman 3:00p Rawhide Gilligan's Island Three Hour Tour 3:30p The Rifleman 3:30p 4:00p Have Gun, Will Travel 4:00p Wagon Train 4:30p Wanted: Dead or Alive 4:30p 5:00p Adam-12 The Rifleman Mama's Family 5:00p 5:30p Adam-12 The Rifleman Mama's Family 5:30p 6:00p The Flintstones 6:00p The Love Boat 6:30p Happy Days 6:30p The Three Stooges 7:00p M*A*S*H M*A*S*H 7:00p 7:30p M*A*S*H M*A*S*H 7:30p 8:00p The Andy Griffith Show 8:00p 8:30p The Andy Griffith Show Svengoolie Columbo 8:30p 9:00p Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. -

The Parasocial Contact Hypothesis Edward Schiappa, Peter B

Communication Monographs Vol. 72, No. 1, March 2005, pp. 92–115 The Parasocial Contact Hypothesis Edward Schiappa, Peter B. Gregg, & Dean E. Hewes We propose a communication analogue to Allport’s (1954) Contact Hypothesis called the Parasocial Contact Hypothesis (PCH). If people process mass-mediated parasocial interaction in a manner similar to interpersonal interaction, then the socially beneficial functions of intergroup contact may result from parasocial contact. We describe and test the PCH with respect to majority group members’ level of prejudice in three studies, two involving parasocial contact with gay men (Six Feet Under and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy) and one involving parasocial contact with comedian and male transvestite Eddie Izzard. In all three studies, parasocial contact was associated with lower levels of prejudice. Moreover, tests of the underlying mechanisms of PCH were generally supported, suggesting that parasocial contact facilitates positive parasocial responses and changes in beliefs about the attributes of minority group categories. Keywords: Parasocial; Contact Hypothesis; Prejudice; Television Studies One of the most important and enduring contributions of social psychology in the past 50 years is known as the Contact Hypothesis (Dovidio, Gaertner, & Kawakami, 2003). Credited to Gordon W. Allport (1954), the Contact Hypothesis, or Intergroup Contact Theory, states that under appropriate conditions interpersonal contact is one of the most effective ways to reduce prejudice between majority and minority group members. Coincidentally, two years after Allport’s book, The Nature of Prejudice, was published, Horton and Wohl (1956) argued for studying what they dubbed para-social interaction: “One of the most striking characteristics of the new mass media—radio, Edward Schiappa (Ph. -

The Operation of the Fugitive Slave Law the OPERATION of THE

150 The Operation of the Fugitive Slave Law THE OPERATION OF THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW IN WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA,FROM 1850 to 1860 By IRENE E. WILLIAMS* Negro slavery engrossed the whole attention of the country during the decade from 1850 to 1860. The "Under- ground Railroad" was a form of combined defiance of national laws on the ground that they were unjust and oppressive. The Underground Railroad was the oppor- tunity for the bold and adventurous ;ithad the excitement of piracy, the secrecy of burglarly, the daring of insurrec- tion ;it developed coolness, indifference to danger and quick- ness of resource." (1) In the course of the sixty years immediately preceding the outbreak of the Rebellion, the Northern states became traversed by numerous secret pathways leading from South- ern bondage to Canadian liberty. Even in colonial times there was difficulty in recovering fugitive slaves because of the aid rendered them by friends. (2) For the acceptance and adoption of the ordinance of 1787 and the United States constitution, clauses relative to the rendition of fugitive slaves were necessary. In1793 the first Fugitive Slave Law was enacted. This was rendered nugatory in1842, by the judicial decision in the famous case of "Prigg versus Pennsylvania." Incorporated in the com- promise measures of 1850 was the Fugitive Slave Law. (3) Under this law the alleged fugitive was denied trial by jury; was forbidden to testify in his own behalf; could not summon witnesses, and was subject to the law though he might have escaped years before it was enacted. Should the judge decide against the negro his fee was ten dollars ;should he decide for the accused it was but five. -

Ambushes and Unprovoked Attacks: Assaults on Our Naton’S Law Enforcement Ofcers

Ambushes and Unprovoked Attacks: Assaults on Our Naton’s Law Enforcement Ofcers Jefrey A. Daniels, Ph.D. West Virginia University College of Educaton and Human Resources Department of Counseling, Rehabilitaton Counseling, and Counseling Psychology James J. Sheets, Ph.D. Federal Bureau of Investgaton Criminal Justce Informaton Services Division Crime Statstcs Management Unit Philip D. Wright Federal Bureau of Investgaton Criminal Justce Informaton Services Division Crime Statstcs Management Unit Brian R. McAllister Federal Bureau of Investgaton Criminal Justce Informaton Services Division Crime Statstcs Management Unit AMBUSHES and UNPROVOKED ATTACKS i This report is in the public domain. Authorizaton to reproduce this publicaton in whole or in part is granted. The accompanying citaton is as follows: Daniels, J., Sheets, J., Wright, P., & McAllister, B. (2018). Ambushes and Unprovoked Atacks: Assaults on Our Naton’s Law Enforcement Ofcers. West Virginia University and the Federal Bureau of Investgaton, U.S. Department of Justce, Washington, D.C. ii AMBUSHES and UNPROVOKED ATTACKS NOTICE This publicaton was prepared by the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor the United States Department of Justce, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any informaton, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that in use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specifc commercial product, process, or service by trade name, mark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily consttute or imply its endorsement, recommendatons, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or refect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof.