A Historical/Critical Analysis of the Tv Series the Fugitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Listeners: Locating Nostalgia, Domesticity and Shared Listening Practices in Contemporary Horror Podcasting

Welcome back listeners: locating nostalgia, domesticity and shared listening practices in Contemporary horror podcasting. Danielle Hancock (BA, MA) The University of East Anglia School of American Media and Arts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Page 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? Pages 3-29 Section One: Remediating the Horror Podcast Pages 49-88 Case Study Part One Pages 89 -99 Section Two: The Evolution and Revival of the Audio-Horror Host. Pages 100-138 Case Study Part Two Pages 139-148 Section Three: From Imagination to Enactment: Digital Community and Collaboration in Horror Podcast Audience Cultures Pages 149-167 Case Study Part Three Pages 168-183 Section Four: Audience Presence, Collaboration and Community in Horror Podcast Theatre. Pages 184-201 Case Study Part Four Pages 202-217 Conclusion: Considering the Past and Future of Horror Podcasting Pages 218-225 Works Cited Pages 226-236 1 Acknowledgements With many thanks to Professors Richard Hand and Mark Jancovich, for their wisdom, patience and kindness in supervising this project, and to the University of East Anglia for their generous funding of this project. 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? The origin of this thesis is, like many others before it, born from a sense of disjuncture between what I heard about something, and what I experienced of it. The ‘something’ in question is what is increasingly, and I believe somewhat erroneously, termed as ‘new audio culture’. By this I refer to all scholarly and popular talk and activity concerning iPods, MP3s, headphones, and podcasts: everything which we may understand as being tethered to an older history of audio-media, yet which is more often defined almost exclusively by its digital parameters. -

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2007 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The life and career of actor Anthony Perkins seems almost like a movie script from the times in which he lived. One of the dark, vulnerable anti-heroes who gained popularity during Hollywood's "post-golden" era, Perkins began his career as a teen heartthrob and ended it unable to escape the role of villain. In his personal life, he often seemed as tortured as the troubled characters he played on film, hiding--and perhaps despising--his true nature while desperately seeking happiness and "normality." Perkins was born on April 4, 1932 in New York City, the only child of actor Osgood Perkins and Janet Esseltyn Rane. His father died when he was only five, and Perkins was reared by his strong-willed and possibly abusive mother. He followed his father into the theater, joining Actors Equity at the age of fifteen and working backstage until he got his first acting roles in summer stock productions of popular plays like Junior Miss and My Sister Eileen. He continued to hone his acting skills while attending Rollins College in Florida, performing in such classics as Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest. Perkins was an unhappy young man, and the theater provided escape from his loneliness and depression. "There was nothing about me I wanted to be," he told Mark Goodman in a People Weekly interview. "But I felt happy being somebody else." During his late teens, Perkins went to Hollywood and landed his first film role in the 1953 George Cukor production, The Actress, in which he appeared with Spencer Tracy. -

Anthology Drama: the Case of CBS Les Séries Anthologiques Durant L’Âge D’Or De La Télévision Américaine : Le Style Visuel De La CBS Jonah Horwitz

Document generated on 09/26/2021 8:52 a.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Visual Style in the “Golden Age” Anthology Drama: The Case of CBS Les séries anthologiques durant l’âge d’or de la télévision américaine : le style visuel de la CBS Jonah Horwitz Fictions télévisuelles : approches esthétiques Article abstract Volume 23, Number 2-3, Spring 2013 Despite the centrality of a “Golden Age” of live anthology drama to most histories of American television, the aesthetics of this format are widely URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015184ar misunderstood. The anthology drama has been assumed by scholars to be DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015184ar consonant with a critical discourse that valued realism, intimacy and an unremarkable, self-effacing, functional style—or perhaps even an “anti-style.” See table of contents A close analysis of non-canonical episodes of anthology drama, however, reveals a distinctive style based on long takes, mobile framing and staging in depth. One variation of this style, associated with the CBS network, flaunted a virtuosic use of ensemble staging, moving camera and attention-grabbing Publisher(s) pictorial effects. The author examines several episodes in detail, demonstrating Cinémas how the techniques associated with the CBS style can serve expressive and decorative functions. The sources of this style include the technological limitations of live-television production, networks’ broader aesthetic goals, the ISSN seminal producer Worthington Miner and contemporaneous American 1181-6945 (print) cinematic styles. 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Horwitz, J. (2013). Visual Style in the “Golden Age” Anthology Drama: The Case of CBS. -

The Ledger and Times, July 19, 1958

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 7-19-1958 The Ledger and Times, July 19, 1958 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, July 19, 1958" (1958). The Ledger & Times. 3368. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/3368 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Selected As A Best All Round Kentucky Community Newspaper JULY 18, 195g First .. Largest Circulation In with The City Local News Largest 40 • and Circulation In Local PictureA The Comity IN OUR 79th YEAR Murra KN, Saturda Afternoon, 19 1958 MURRAY POPULATION 10,100 Vol. LXXIX No. 171 se natural carelessness United Press people. Long and ir- >ties of work are not in orderly check-ups of ints, and farm peegie to overlook little thiNs iger life and limb. A ard in the barn floor. UNICIPAL PARKING VOTED BY COUNCIL pa, rubbish left idly Hair Styling Show Pre-School Clinic e all booby traps of To Appear Present Location Of Beale Number land Number6 Not To Be Held Here U.S. Plane Is Scheduled The Devry's Beauty Supply A pre-school clinic will. be to 90 In New Directory."2-5" System Used Company will sponsor a hair held at the Hearth Department Home To Park 75 Cars styling show in Murray for N. -

I'kaai Party Where the Two Families Meet "Ft "Copsand CONSULT OUR LISTINGS for LAST MINUTE Tv Coiwuum Mc

14-T- HE CAROLINA TIMES SAT., JULY 28, 1979 ; REFLECTIONS SWORD OF JUSTICE The n 0 - CJ BASEBALL Atlanta Braveava . woundedJackColerelleeonHec- Houston Astros tor to finish the lob of proving that O WILD KINGDOM a corrupt police commissioner w: 7:00 and the mob that 'owns' him were THIEVES LIKE US for of an N FOOTBALL responsible the slaying O 60 Tampa Bay Buccaneers va Wa- honest cop. (Repeat; mina.) A backwoods MOVIE -- fugitive and young, shington Redskins HBO (SUSPENSE) girl fall in love in Mississippi during MASTERPIECE THEATRE 'I. "Capricorn One" Elliott Gould, O Karen Black. A stumbles the Depression, in 'Thieves Like Claudius' 'Reign of Terror' Tiber- reporter Us,' directed by Robert Altman ius' haathe onto the acoop of the century-man'- s palace guard emperor to Mars and Keith Carradine (pic- cut off from the outside first space flight starring totally 15 tured) and Shelley Ouvall, premier-in- g world - at Sejanus' order. So how wasahoaxl(RatedPG)(2hra., on television Aug. 4, on 'The can Antonia possibly warn mins.) CBS 10:30 Saturday Night Movies.' RESURRECTION mins.) O GOSPEL Based on the Edward Anderson GD BLACK REFLECTIONS novel that also inspired the earlier N FOOTBALL SOAP FACTORY 11:00 'They Live By Night,' the movie 8 tells the love of Bowie n LAWRENCE WELK SHOW OOOOnews tragic story CJ HEE HAW Conway Twltty. gd odd couple who has HIGH (Carradine), escaped Dave and Sugar, Grandpa, CI 12 O'CLOCK from a prison work farm, and Ramona and Aliaa Jones. (60 CJ SECOND CITY TV Keechie (Miss Duvall), the mins.) V 11:15 uneducated young innocent he CJ M SEARCH OF OO ABC NEWS meets. -

Gunsmoke: an Investigation of Conversational Implicature and Guns & Ammo Magazine

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 Gunsmoke: An investigation of conversational implicature and Guns & Ammo magazine Kerry Lynn Winn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Winn, Kerry Lynn, "Gunsmoke: An investigation of conversational implicature and Guns & Ammo magazine" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2069. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2069 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GUNSMOKE: AN INVESTIGATION OF CONVERSATIONAL IMPLICATURE AND GUNS & AMMO MAGAZINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Kerry Lynn Winn March 2002 GUNSMOKE: AN INVESTIGATION OF CONVERSATIONAL IMPLICATURE AND GUNS & AMMO MAGAZINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Kerry Lynn Winn March 2002 Approved by: Ph . D . , I Chair, Sunny Hyon English Date Rong Chen, Ph.D. ABSTRACT In the United States, numerous citizens fear that their Second Amendment right to bear arms will be obliterated. One text that discusses this issue is a popular gun enthusiast's magazine. Guns & Ammo. I will analyze this magazine's content through linguistics, particularly Grice's implicature. As a result I hope it will give me a better viewpoint of the gun community's perspective regarding firearms. -

The Wenhamite WENHAM RESOURCE COA 10 SCHOOL STREET March 2015 978-468-5534 [email protected]

Jim.Reynolds, Director/Outreach Coordinator: (978) 468-5529 Wenham Resource Center/Monday - Friday 9:00 am - 4:00 pm The Wenhamite WENHAM RESOURCE COA 10 SCHOOL STREET March 2015 978-468-5534 [email protected] Volume 2, Issue 3 For the first time ever, overweight people outnumber average people in America. Doesn't that make overweight the average then? Last month you were fat, now you're average - hey, let's get a pizza! ~ Jay Leno The Winter has brought more snow and ice than any winter in recent history, since ‘78. We received many calls for help and were unable to respond due to demand far exceeding supply in the way of help. The thought of warm weather is frightening if you ask me and we’ll be standing by to help in any way we can. Wenham DPW Appreciation Breakfast will be planned for April, 2015 for the March we plan to resume truly exceptional work done keeping our roads and sidewalks safe and clear. some of our classes and we The work of this department has been exemplary and should make you proud to be residents of Wenham. Driving around the Northshore has been hit or have new groups getting miss with so much snow and nowhere to put it. We have a great team of underway from Memoir writing dedicated people in our Police, Fire and DPW departments. Thank you! to Folly Cove crafting and design. We are excited about starting new programs, so call if you want to discuss it. We continue to visit people around town to learn more about ways we can better Friends of the Wenham Council on Aging - A Spring/Summer furniture sale is serve. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Miriam Colón-Valle Doctor of Humane Letters As a Lifetime Advocate For

Miriam Colón-Valle Doctor of Humane Letters As a lifetime advocate for equitable access to the arts, the founder of the Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, and a trailblazing stage, film, and television actress, you, Miriam Colón-Valle, are a true Latina icon. Born and raised in Ponce, Puerto Rico, you started in the theater at the age of 12, and in just three short years, you landed your first feature film role, as Lolita in Los peloteros, or The Ball Players. The movie was a production of the civic-minded DIVEDCO, the Division of Community Education of Puerto Rico, a program that sought to stimulate artistic production. At the urging of your teachers and mentors, you moved to New York City to further your training and gained admission to the Actors Studio after a single audition before famed actor-directors Elia Kazan and Lee Strasberg. Your stage credits include performances on Broadway and at Minneapolis’s Guthrie Theater and Los Angeles’s Mark Taper Forum. Your long list of Hollywood credits includes the television series Bonanza, Gunsmoke, and NYPD Blue, as well as the films One-Eyed Jacks and The Appaloosa, both opposite Marlon Brando. You also played Mama Montana in Brian De Palma’s Scarface, starring Al Pacino, and had memorable roles in John Sayles’s Lone Star and City of Hope, Sydney Pollack’s Sabrina, and Billy Bob Thornton’s All the Pretty Horses. More recently, you were honored with the Imagen Award for your title role in 2013’s Bless Me, Última, Carl Franklin’s adaptation of the classic Chicano novel by Rudolfo Anaya. -

American International Pictures Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary •JO NO. 47 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL PICTURES RETROSPECTIVE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART The Department of Film of The Museum of Modern Art will present a retrospective exhibition of films from American International Pictures beginning July 26 and running through August 28, 1979. The 38 film retrospective, which coincides with the studio's 25th anniversary, was selected from the company's total production of more than 500 films, by Adrienne Mancia, Curator, and Larry Kardish, Associate Curator, of the Museum's Department of Film. The films, many in new 35mm prints, will be screened in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium and, concurrent with the retro spective, a special installation of related film stills and posters will be on view in the adjacent Auditorium Gallery. "It's extraordinary to see how many filmmakers, writers and actors — now often referred to as 'the New Hollywood'—took their first creative steps at American International," commented Adrienne Mancia. "AIP was a good training ground; you had to work quickly and economically. Low budgets can force you to find fresh resources. There is a vitality and energy to these feisty films that capture a certain very American quality. I think these films are rich in information about our popular culture and we are delighted to have an opportunity to screen them." (more) II West 53 Street, New York, NY. 10019, 212-956-6100 Coble: Modernart NO. 47 Page 2 Represented in the retrospective are Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Jack Nicholson, Annette Funicello, Peter Fonda, Richard Dreyfuss, Roger Corman, Ralph Bakshi, Brian De Palma, John Milius, Larry Cohen, Michael Schultz, Dennis Hopper, Michelle Phillips, Robert De Niro, Bruce Dern, Michael Landon, Charles Bronson, Mike Curb, Richard Rush, Tom Laughlin, Cher, Richard Pryor, and Christopher Jones. -

24)0 M « » R C T » 2 "7 T L I Johnny Jones" (1989

derer of his parents. per. A former country singer, his life pines following the Spanish- ® **% ‘Rafferty and the Gold and career ruined by alcoholism, American War. Dust Twins” (1975. Comedy) Alan falls in love with a Texas motel 114)0 Arkin, Sally Kelierman. Two young owner and decides to make a female drifters kidnap a depressed comeback. a ★ "It's Alive!" (1968, Science driving instructor and launcn a zany Fiction) Tommy Kirk, Shirley crime spree. EVENING Bonne. A lunatic's plot to trap three tors seem to vanish when they strangers in an Ozark cave with a threaten the privacy of a teen-age prehistoric m onster backfires when girt who lives with her unseen 74)0 the creature sets its sights on him. Father in a mysterious house. FRIDAY, a ** V i "The Adventures of 124)0 M « » r c T » 2 "7 t l i Johnny Jones" (1989. Drama) Ri 9:30 chard Love, Ida Gregory. In 1943 [41 QD ★★ "La Parfaite Forme” ® **W "Johnnie Mae Gibson: Wales, an imaginative boy’s work! (1985, Cornedie) John Travolta, Ja FBI" (1986, Drama) Lynn Whitfield. M O R N IN G Is changed by tne arrival of children mie Lee Curtis. Un journalists de Howard E. Rollins Jr. Fact-based evacuated from Liverpool and the I'hebdomadaire “Rolling Stone" story of a Southern woman who ov 84)0 introduction of American bobble prepare un reportage a sensation ercame a poverty-stricken child sur les centres de conditionnement (8 * * “Crooks in Cloisters" (1963. gum. hood and the strains of balancing a 7:30 physique, bars de rencontres nou marriage and a career to achieve Comedy) Ronald Fraser. -

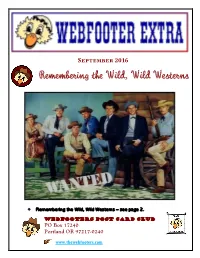

The Webfooter

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke.