'WATER WARS' HYPOTHESIS in SOUTHERN AFRICA LA Swatuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAAS RR46 Smeadzim 1.Pdf

Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 46 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: Zimbabwe Country Report Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 46 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editor: Vaun Cornell Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: Pamela Ngwenya Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms and abbreviations ...................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

HSRC CWC.Indb

www.hsrcpress.ac.za from CRISIS! download Free WHAT CRISIS? THE MULTIPLE DIMENSIONS OF THE ZIMBABWEAN CRISIS Edited by Sarah Chiumbu and Muchaparara Musemwa Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa www.hsrcpress.ac.za First published 2012 ISBN (soft cover): 978-0-7969-2383-7 ISBN (pdf): 978-0-7969-2384-4 ISBN (e-pub): 978-0-7969-2385-1 © 2012 Human Sciences Research Council The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Human Sciences Research Council (‘the Council’) or indicate that the Council endorses the views of the authors. In quoting from this publication, www.hsrcpress.ac.za readers are advised to attribute the source of the information to the individual author concerned and not to the Council. from Chapter 1 is a revised version of a paper originally published in the Journal of Developing Societies 26(2): 165–206, copyright © Sage Publications (all rights reserved) and is reproduced here with the permission of the copyright holders and the publishers, Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi. download Free Chapter 2 is a revised version of a paper by Mukwedeya T (2011) originally published as ‘Zimbabwe’s saving grace: The role of remittances in household livelihood strategies in Glen Norah, Harare’ in the South African Review of Sociology 42(1): 116–130, copyright © South African Sociological Association reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the South African Sociological Association. Chapter 4 is a revised version of a paper originally published in M Palmberg & R Primorac (eds) Skinning the Skunk: Facing Zimbabwean Futures (2005), copyright © the editors and the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI) and is reproduced here with the permission of the editors and the NAI. -

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 18, No. 9

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 18, No. 9 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuzn198709 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zimbabwe News, Vol. 18, No. 9 Alternative title Zimbabwe News Author/Creator Zimbabwe African National Union Publisher Zimbabwe African National Union (Harare, Zimbabwe) Date 1987-09-00 Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe, Mozambique, South Africa, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1987 Source Northwestern University Libraries, L968.91005 Z711 v.18 Rights By kind permission of ZANU, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front. Description Editorial. Address to the Central Committee by the President and First Secretary of ZANU (PF) Comrade R.G. -

A Biographical Study of Bishop Ralph Edward Dodge 1907 – 2008

ABSTRACT Toward a New Church in a New Africa: A Biographical Study of Bishop Ralph Edward Dodge 1907 – 2008 This biography of a Methodist Bishop, Ralph Edward Dodge is an extensive look into how, as a missionary, mission board executive, and bishop, Dodge applied principles of indigenization he embraced as a young man preparing for missionary work to the complexities of ministry in Southern Africa when empires were withdrawing and new nations were forming. Written by an African, the dissertation examines Dodge’s impact upon the several countries in which he was involved as a churchman ‒ countries that would soon move from imperial subjugation to independence. Ralph Edward Dodge (1907–2008) was an American missionary and Bishop of the Methodist Church and United Methodist Church. He was born in Iowa and went to Africa in 1936 at age 29. He began his missionary career in the Portuguese colony of Angola. Except for four years during World War II, he would serve there until 1950. During the war, he continued his postgraduate work, obtaining two more degrees, including a PhD. Afterwards, Dodge and his family returned to Africa. In 1950, he was asked to serve as Executive Secretary for Africa and Europe at the Methodist Church’s Board of Missions in New York. Six years later, the Reverend Doctor Dodge would return to Africa as Bishop Dodge, the first Methodist Bishop elected by the Africa Central Conference, and the only American. His Episcopal Area included the colonial territories of Angola, Mozambique, and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). When his twelve-year term was ended, he was elected “Bishop for Life.” Bishop Dodge remained in Africa until his “retirement” in 1968. -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

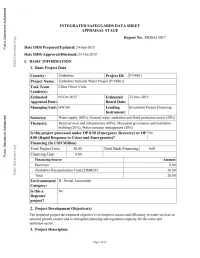

Date ISDS Prepared/Updated: 24-Sep-2015 O Date ISDS Approved/Disclosed: 01-Oct-2015 I

INTEGRATED SAFEGUARDS DATA SHEET APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: ISDSA15017 0 Public Disclosure Authorized Date ISDS Prepared/Updated: 24-Sep-2015 o Date ISDS Approved/Disclosed: 01-Oct-2015 I. BASIC INFORMATION 1. Basic Project Data Country: Zimbabwe Project ID: P154861 Project Name: Zimbabwe National Water Project (P154861) Task Team Chloe Oliver Viola Leader(s): Estimated 05-Oct-2015 Estimated 23-Nov-2015 Appraisal Date: Board Date: Public Disclosure Authorized Managing Unit: GWA01 Lending Investment Project Financing Instrument: Sector(s): Water supply (80%), General water, sanitation and flood protection sector (20%) Theme(s): Rural services and infrastructure (60%), Municipal governance and institution building (20%), Water resource management (20%) Is this project processed under OP 8.50 (Emergency Recovery) or OP No 8.00 (Rapid Response to Crises and Emergencies)? Financing (In USD Million) Total Project Cost: 20.00 Total Bank Financing: 0.00 Financing Gap: 0.00 Public Disclosure Authorized Financing Source Amount Borrower 0.00 Zimbabwe Reconstruction Fund (ZIMREF) 20.00 Total 20.00 Environmental B - Partial Assessment Category: Is this a No Repeater project? 2. Project Development Objective(s) Public Disclosure Authorized The proposed project development objective is to iimprove access and efficiency in water services in selected growth centers and to strengthen planning and regulation capacity for the water and sanitation sector. 3. Project Description Page 1 of 15 The project will have three components with indicative costing as -

Rosa 451V02 Zimbabwe Flood

ZIMBABWE: Flood Snapshot (as of 09 March 2017) Situational Indicators Flood Risk Areas Homeless people Homesteads damaged 1,985 2,579 Zambia Mashonaland Mazowe Central Districts Affected Fatalities Mazowe Bridge Mashonaland 45 246 West Zambezi Harare Funding Raised Dams Breached Victoria Falls USD M Gwai 14.5 140 Mashonaland *Government raised Dahlia East Matabeleland Odzi Midlands Hydrological Update North Manicaland Expected river level/flow at this time of season (m3/s) Zambezi river Odzi river Bulawayo Odzi Gorge River level/flow as at 03/03/2017 3 69.1m3/s as percentage of expected 1556m /s Increase in flows due Increase in flows. River level/flow as at 27/02/2017 Moderate flood risk in as percentage of expected to incoming runoff from Masvingo the upstream countries Manicaland Normal river level/flow Runde at this time of season Matabeleland South Mzingwane Confluence with Tokwe Botswana 107% Legend 91% 123% Limpopo Mozambique Runde river 87% Mazowe river Flood Affected Districts 429% Worst Affected Districts 168.4m3/s 133% 167.4m3/s Site where river flow measured South Africa Increase in flows causing Flows are now flooding problems in Chivi. 212% increasing and are There is high risk of flooding 352% above average. Situation Update in Runde up to the confluence with Save. Zimbabwe has appealed for assistance after declaring floods a national disaster. Almost 250 people have been killed and about 2,000 people have been left homeless, with around 900 351% people displaced to a camp in Tsholostho in Matabeleland North. Much of the heavy rains 367% received over the past month can be attributed to Tropical Cyclone DINEO, which crossed 857% southern and western Zimbabwe as a powerful storm system in mid-February. -

Salt Intrusion in the Pungue Estuary, Mozambique

Ivar Abas and Hugo Hagedooren Salt intrusion in the Pungue estuary, Mozambique A case study on modelling the salinity distribution in the Pungue estuary Delft, March 2017 2 Salt intrusion in the Pungue estuary, Mozambique A case study on modelling the salinity distribution in the Pungue estuary By Ivar Abas and Hugo Hagedooren In fulfilment of the requirements of an Additional Master Thesis Master Civil Engineering Track Water Management at the Delft University of Technology, Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Ir. H.H.G. Savenije, Dr. Ir. S.G.J. Heijman, Ir. W.M.J. Luxemburg An electronic version of this thesis is available at http://repository.tudelft.nl/ 3 Notation 푎 Cross-sectional convergence length [m] 퐴 Tidal average cross-sectional area [m2] 2 퐴0 Cross-sectional area at the estuary mouth [m ] 2 퐴푟 Cross-sectional area of the river [m ] 푏 Width convergence length [m] 퐵 Tidal average estuary width [m] 퐵0 Width at the estuary mouth [m] 퐵푟 Width of the river [m] 퐶 Chézy coefficient [m0.5/s] 퐷 Tidal average longitudinal dispersion [m2/s] 2 퐷0 Dispersion coefficient at the estuary mouth [m /s] 2 퐷 Dispersion coefficient during HWS, TA or LWS [m /s] 퐷(푥) Dispersion coefficient as a function of 푥 [m2/s] 퐸 Tidal excursion [m] 퐸0 Tidal excursion at the estuary mouth [m] Gravitational acceleration [m/s2] ℎ̅ Tidal average depth [m] ℎ0 Depth at the estuary mouth [m] 퐻 Tidal range [m] 퐾 Van der Burgh’s coefficient [-] 퐿 Salt intrusion length [m] 푃 Wetted perimeter [m] 푃 Tidal prism [m3] 푃푛 Net rainfall in an estuary [m/s] 푞 Coefficient of the advective -

Zimbabwe Livelihood Zone Profiles. December 2010

Zimbabwe Livelihoods Zone VAC ZIMBABWE Profiles Vulnerability Assessment Committee 15 February 2010 The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) is Chaired by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) which is housed at the Scientific Industrial Research and Developing Council (SIRDC), Harare, Zimbabwe. Acknowledgements The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) would like to express its appreciation for the financial, technical and logistical support that the following agencies provided towards the data collection, analysis and writing-up of the Revised Livelihoods profiles for Zimbabwe; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation Development and Mechanizations’ Department of Agricultural Extension Services (AGRITEX) Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare’s Department of Social Welfare Ministry of Finance’s Central Statistical Office (CSO) Ministry of Education’s Curriculum Development Ministry of Transport’s Department of Meteorological Services United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) United Nations’ Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) World Vision (WV) OXFAM ACTIONAID Save the Children United Kingdom (SC-UK) Southern Africa Development Community Regional Vulnerability Assessment Committee (RVAC) United States of America International Development Agency (USAID) Department for International Development (DFID) The European Commission (EC) FEG (The Food Economy Group) The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) The revision -

Pdf | 218.74 Kb

SOUTHERN AFRICA Flash Update No.11 – Tropical Cyclone Eloise As of 28 January 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • More than 270,000 people have been affected by Eloise across Southern Africa, including 267,289 in Mozambique, more than 1,000 in Zimbabwe and more than 1,000 in Eswatini. • The death toll from Eloise has risen to 21, including 11 in Mozambique, 3 in Zimbabwe, 4 in Eswatini, 2 in South Africa and 1 in Madagascar. • With flood waters present in multiple locations, the risk of water-borne diseases, including cholera, is high. • Tens of thousands of hectares of crops have been flooded due to the Eloise weather system, which could have consequences for the next harvest and food security in the period ahead. SITUATION OVERVIEW The Eloise weather system has left at least 21 people dead -11 in Mozambique, 3 in Zimbabwe, 4 in Eswatini, 2 in South Africa and 1 in Madagascar- and affected more than 270,000 people across Southern Africa, according to preliminary information which continues to be updated as new data becomes available. Although the damage wrought by Eloise to date has been less widespread than Tropical Cyclone Idai in 2019, homes, crops and infrastructure in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Eswatini and South Africa have been damaged or destroyed. In Mozambique, the number of people affected by Tropical Storm Eloise has risen to 267,289, as assessment teams have reached areas impacted by the storm and further information is becoming available. At least 20,167 people are sheltering in 32 temporary accommodation centres after being displaced by flooding, where urgent needs include clean water and sanitation to prevent disease outbreaks. -

Manicaland-Province

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Manicaland Buhera BANGURE ZVAVAHERA VILLAGE WARD 19 CHIEF NYASHANU BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera BETERA HEADMAN BETERA CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera BHEGEDHE BHEGEDHE VILLAGE CHIEF CHAMUTSA Secondary Manicaland Buhera BIKA KWARAMBA VILLAGE WARD 16 CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera BUHERA GAVA VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIEF MAKUMBE BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHABATA MUVANGIRWA VILLAGE WARD 29 Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHANGAMIRE MATSVAI VILLAGE WARD 32 NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAPANDUKA CHAPANDUKA VILLAGE CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAPWANYA CHAPWANYA HIGH SCHOOL WARD 2 BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAWATAMA CHAWATAMA VILLAGE WARD 31 CHIEF MAKUMBE Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIMBUDZI MATASVA VILLAGE WARD 32 CHIEF NYASHANU CHINHUWO VILLAGE CHIWENGA TOWNSHIP CHIEF Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHINHUWO NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIROZVA CHIROZVA VILLAGE Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIURWI CMAKUVISE VILLAGE WARD 32 Secondary Manicaland Buhera DEVULI NENDANDA VILLAGE CHIEF CHAMUTSA WARD 33 Secondary Manicaland Buhera GOSHO SOJINI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIEF MAKUMBE Secondary Manicaland Buhera GOTORA GOTORA VILLAGE WARD 22 CHIEF NYASHANU BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GUNDE MABARA VILLAGE WARD 9 CHIEF CHITSUNGE BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GUNURA CHIEF CHAMUTSA NEMUPANDA VILLAGE WARD 30 BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GWEBU GWEBU SECONDARY GWEBU VILLAGE Secondary Manicaland Buhera HANDE KARIMBA VILLAGE