MIGRATION PROFILE Study on Migration Routes in West and Central Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Immeuble CCIA, Avenue Jean Paul II, 01 BP 1387, Abidjan 01 Cote D'ivoire

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP Immeuble CCIA, Avenue Jean Paul II, 01 BP 1387, Abidjan 01 Cote d’Ivoire Gender, Women and Civil Society Department (AHGC) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Telephone: +22520264246 Title of the assignment: Consultant-project coordinator to help the Department of Gender, Women and Civil Society (AHGC) in TSF funded project (titled Economic Empowerment of Vulnerable Women in the Sahel Region) in Chad, Mali and Niger. The African Development Bank, with funding from the Transition Support Facility (TSF), hereby invites individual consultants to express their interest for a consultancy to support the Multinational project Economic Empowerment of Vulnerable Women in three transition countries specifically Chad, Mali and Niger Brief description of the Assignment: The consultant-project coordinator will support the effective operationalization of the project that includes: (i) Developing the project’s annual work Plan and budget and coordinating its implementation; (ii) Preparing reports or minutes for various activities of the project at each stage of each consultancy in accordance with the Bank reporting guideline; (iii) Contributing to gender related knowledge products on G5 Sahel countries (including country gender profiles, country policy briefs, etc.) that lead to policy dialogue with a particular emphasis on fragile environments. Department issuing the request: Gender, Women and Civil Society Department (AHGC) Place of assignment: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Duration of the assignment: 12 months Tentative Date of commencement: 5th September 2020 Deadline for Applications: Wednesday 26th August 2020 at 17h30 GMT Applications to be submitted to: [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] For the attention of: Ms. -

JPC.CCP Bureau Du Prdsident

Onchoccrciasis Control Programmc in the Volta Rivcr Basin arca Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose dans la R6gion du Bassin de la Volta JOIN'T PROCRAMME COMMITTEE COMITE CONJOINT DU PROCRAMME Officc of the Chuirrrran JPC.CCP Bureau du Prdsident JOINT PROGRAII"IE COMMITTEE JPC3.6 Third session ORIGINAL: ENGLISH L Bamako 7-10 December 1982 October 1982 Provisional Agenda item 8 The document entitled t'Proposals for a Western Extension of the Prograncne in Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ssnegal and Sierra Leone" was reviewed by the Corrrittee of Sponsoring Agencies (CSA) and is now transmitted for the consideration of the Joint Prograurne Conrnittee (JPC) at its third sessior:. The CSA recalls that the JPC, at its second session, following its review of the Feasibility Study of the Senegal River Basin area entitled "Senegambia Project : Onchocerciasis Control in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, l,la1i, Senegal and Sierra Leone", had asked the Prograrrne to prepare a Plan of Operations for implementing activities in this area. It notes that the Expert Advisory Conrnittee (EAC) recormnended an alternative strategy, emphasizing the need to focus, in the first instance, on those areas where onchocerciasis was hyperendemic and on those rivers which were sources of reinvasion of the present OCP area (Document JPC3.3). The CSA endorses the need for onchocerciasis control in the Western extension area. However, following informal consultations, and bearing in mind the prevailing financial situation, the CSA reconrnends that activities be implemented in the area on a scale that can be managed by the Prograrmne and at a pace concomitant with the availability of funds, in order to obtain the basic data which have been identified as missing by the proposed plan of operations. -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

World Bank Document

69972 Options for Preparing a Sustainable Land Management (SLM) Program in Mali Consistent with TerrAfrica for World Bank Engagement at the Country Level Introduction Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Background and rationale: 1. One of the most environmentally vulnerable areas of the world is the drylands of sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and Southeast Africa. Mali, as with other dryland areas in this category, suffers from droughts approximately every 30 years. These droughts triple the number of people exposed to severe water scarcity at least once in every generation, leading to major food and health crisis. In general, dryland populations lag far behind the rest of the world in human well-being and development indicators. Similarly, the average infant mortality rate for dryland developing countries exceeds that for non-dryland countries by 23% or more. The human causes of degradation1 and desertification2 include direct factors such as land use (agricultural expansion in marginal areas, deforestation, overgrazing) and indirect factors (policy failures, population pressure, land tenure). The biophysical impacts of dessertification are regional and global climate change, impairment of carbon sequestation capacity, dust storms, siltation into rivers, downstream flooding, erosion gullies and dune formation. The social impacts are devestating- increasing poverty, decreased agricultural and silvicultural production and sometimes Public Disclosure Authorized malnutrition and/or death. 2. There are clear links between land degradation and poverty. Poverty is both a cause and an effect of land degradation. Poverty drives populations to exploit their environment unsustainably because of limited resources, poorly defined property rights and limited access to credit, which prevents them from investing resources into environmental management. -

Building Resilience in Africa's Drylands

REGIONAL INITIATIVE FOR AFRICA Building resilience in Africa’s drylands FOCUS COUNTRIES Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. OVERALL GOAL Enhance the capacity of dryland countries to anticipate, mitigate and respond to shocks, threats and crises affecting their livelihoods. ABOUT THE REGIONAL INITIATIVE Populations in Africa are increasingly exposed to the negative impact of natural and human-induced disasters such as drought, floods, disease epidemics and conflicts which threaten the agriculture production systems and livelihoods of vulnerable communities. The initiative on “Building Resilience in Africa’s Drylands” was developed to enhance the capacity of these communities to withstand and bounce back from these crises. It aims to strengthen institutional capacity for resilience; support early warning and information management systems; build community level resilience; and respond to emergencies and crises. ZIMBABWE Vegetable farming in Chirumhanzi district. ©FAO/Believe Nyakudjara ZIMBABWE Emergency drought mitigation for livestock in Matabeleland province. ©FAO/Believe Nyakudjara practices and knowledge in the region. The Regional MAKING A DIFFERENCE Initiative also seeks to support countries in meeting one of the key commitments of the Malabo Declaration on The Regional initiative strengthens institutional capacity reducing the number of people in Africa vulnerable to for resilience; supports early warning and information climate change and other threats. management systems; builds community level resilience; and responds to emergencies and crises. Priority actions include: IN PRACTICE > Provide support in areas of resilience policy development and implementation, resilience To achieve resilience in Africa’s drylands in the focus measurement, vulnerability analysis, and strategy countries, the initiative is focusing its efforts on: development and implementation. -

Between Islamization and Secession: the Contest for Northern Mali

JULY 2012 . VOL 5 . ISSUE 7 Contents Between Islamization and FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Between Islamization and Secession: Secession: The Contest for The Contest for Northern Mali By Derek Henry Flood Northern Mali REPORTS By Derek Henry Flood 6 A Profile of AQAP’s Upper Echelon By Gregory D. Johnsen 9 Taliban Recruiting and Fundraising in Karachi By Zia Ur Rehman 12 A Biography of Rashid Rauf: Al-Qa`ida’s British Operative By Raffaello Pantucci 16 Mexican DTO Influence Extends Deep into United States By Sylvia Longmire 19 Information Wars: Assessing the Social Media Battlefield in Syria By Chris Zambelis 22 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 24 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts An Islamist fighter from the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa in the city of Gao on July 16, 2012. - AFP/Getty Images n january 17, 2012, a rebellion 22, disgruntled Malian soldiers upset began in Mali when ethnic about their lack of support staged a coup Tuareg fighters attacked a d’état, overthrowing the democratically Malian army garrison in the elected government of President Amadou Oeastern town of Menaka near the border Toumani Touré. with Niger.1 In the conflict’s early weeks, the ethno-nationalist rebels of the By April 1, all Malian security forces had National Movement for the Liberation evacuated the three northern regions of of Azawad (MNLA)2 cooperated and Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu. They relocated About the CTC Sentinel sometimes collaborated with Islamist to the garrisons of Sévaré, Ségou, and The Combating Terrorism Center is an fighters of Ansar Eddine for as long as as far south as Bamako.4 In response, independent educational and research the divergent movements had a common Ansar Eddine began to aggressively institution based in the Department of Social enemy in the Malian state.3 On March assert itself and allow jihadists from Sciences at the United States Military Academy, regional Islamist organizations to West Point. -

Mali – Beyond Cotton, Searching for “Green Gold”* Yoshiko Matsumoto-Izadifar

Mali – Beyond Cotton, Searching for “Green Gold”* Yoshiko Matsumoto-Izadifar Mali is striving for agricultural diversification to lessen its high dependence on cotton and gold. The Office du Niger zone has great potential for agricultural diversification, in particular for increasing rice and horticultural production. Tripartite efforts by private agribusiness, the Malian government and the international aid community are the key to success. Mali’s economy faces the challenge of Office du Niger Zone: Growing Potential for agricultural diversification, as it needs to lessen Agricultural Diversification its excessive dependence on cotton and gold. Livestock, cotton and gold are currently the In contrast to the reduced production of cotton, country’s main sources of export earnings (5, 25 cereals showed good progress in 2007. A and 63 per cent respectively in 2005). However, substantial increase in rice production (up more a decline in cotton and gold production in 2007 than 40 per cent between 2002 and 2007) shows slowed the country’s economic growth. Mali has the potential to overcome its dependence on cotton (FAO, 2008). The Recent estimates suggest that the country’s gold government hopes to make the zone a rice resources will be exhausted in ten years (CCE, granary of West Africa. 2007), and “white gold”, as cotton is known, is in a difficult state owing to stagnant productivity The Office du Niger zone (see Figure 1), one of and low international market prices, even the oldest and largest irrigation schemes in sub- though the international price of cotton Saharan Africa, covers 80 per cent of Mali’s increased slightly in 2007 (AfDB/OECD, 2008). -

Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger

BURKINA FASO, MALI AND NIGER Vulnerability to COVID-19 Containment Measures Thematic report – April 2020 Any questions? Please contact us at [email protected] ACAPS Thematic report: COVID-19 in the Sahel About this report is a ‘bridge’ between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. It is an area of interaction between African indigenous cultures, nomadic cultures, and Arab and Islamic cultures Methodology and overall objective (The Conversation 28/02/2020). ACAPS is focusing on Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger because these three countries This report highlights the potential impact of COVID-19 containment measures in three constitute a sensitive geographical area. The escalation of conflict in Mali in 2015 countries in the Sahel region: Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. It is based on ACAPS’ global exacerbated regional instability as conflict began to spill across the borders. In 2018 ‘Vulnerability to containment measures’ analysis that highlights how eight key factors can regional insecurity increased exponentially as the conflict intensified in both Niger and shape the impact of COVID-19 containment measures. Additional factors relevant to the Burkina Faso. This led to a rapid deterioration of humanitarian conditions (OCHA Sahel region have also been included in this report. The premise of this regional analysis 24/02/2020). Over the past two years armed groups’ activities intensified significantly in the is that, given these key factors, the three countries are particularly vulnerable to COVID- border area shared by the three countries, known as Liptako Gourma. As a result of 19 containment measures. conflict, the provision of essential services including health, education, and sanitation has This risk analysis does not forecast the spread of COVID-19. -

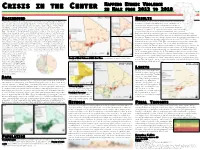

Mapping Ethnic Violence in Mali From

RISIS IN THE ENTER MAPPING ETHNIC VIOLENCE C C IN MALI FROM 2012 TO 2018 BACKGROUND RESULTS This project’s purpose is to analyze where ethnic violence is taking place in Mali since The population maps showed a higher density of people and set- the Tuareg insurgency in January 2012. Chaos from the insurgency created a power tlement in the South, with minimal activity in the North; this is vacuum in the North, facilitating growing control by Islamic militants (“Africa: Mali — consistent with relevant research and presents the divide be- The World Factbook” 2019). While a French-led operation reclaimed the North in tween the two, fueled by imbalances in government resources. 2013, Islamic militant groups have gained control of rural areas in the Center (“Africa: The age of this data (2013) is a potential source of error. The spatial Mali — The World Factbook” 2019). These groups exploited and encouraged ethnic analysis shows that ethnic violence is concentrated in the center of rivalries in Central Mali, stirring up intercommunal violence. Mali’s central and north- Mali, particularly Mopti and along that area of the Burkina Faso border. Conflict ern regions have faced lacking government resources and management, creating events near the border in Burkina Faso were not recorded, but could have aided in grievances between ethnic groups that rely on clashing livelihoods. Two of the key the analysis. There are two clear changes demonstrated by mapping kernel density of ethnic groups forming militias and using violence are the Dogon and Fulani. The vio- individual incidents from the beginning of the Malian crisis (2012-2015) and those lence between these groups is exacerbated by some of the Islamic militant groups from more recent years (2016-2018). -

Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet: Mali

May 2021 Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet Mali Dormino UN Photo/Marco Photo: RECOMMENDED ACTIONS: Mali is characterised by short-term climate variability, and is vulnerable to long-term climate change due to high exposure to the adverse effects The UN Security Council (UNSC) should task the United Nations of climate change, but also high population growth, diminished resilience Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali and multiple violent conflicts. Mali is forecast to become hotter with (MINUSMA) with incorporating climate, peace and security more erratic rainfall, impacting seasonal regularity and increasing the risks as a higher-order priority in its mandate. MINUSMA should risk of droughts and floods. Moreover, conflict, political instability and report to the UNSC on climate security, its effects on the mission weak government institutions undermine effective adaptation to climate mandate, and actions taken to address these problems. change. The UNSC should encourage MINUSMA to work with UN • Climate change may impact seasonal regularity and jeopardise Environment Programme (UNEP) to appoint an Environmental natural resource-based livelihoods. Livelihood insecurity can Security Advisor for prioritising climate, peace and security risks interact with political and economic factors to increase the risk within MINUSMA and for coordinating effective responses with of conflicts over natural resource access and use. the rest of the UN system, the Malian government, civil society, international and regional partners. The Advisor should support • Conflict, agricultural development and changing environmental capacity-building for analysis, reporting and coordinating conditions have affected migratory livestock routes, pushing responses to climate, peace and security risks – particularly in herders into areas where natural resources are under pressure the Malian government and MINUSMA divisions that regularly or shared use is not well defined.