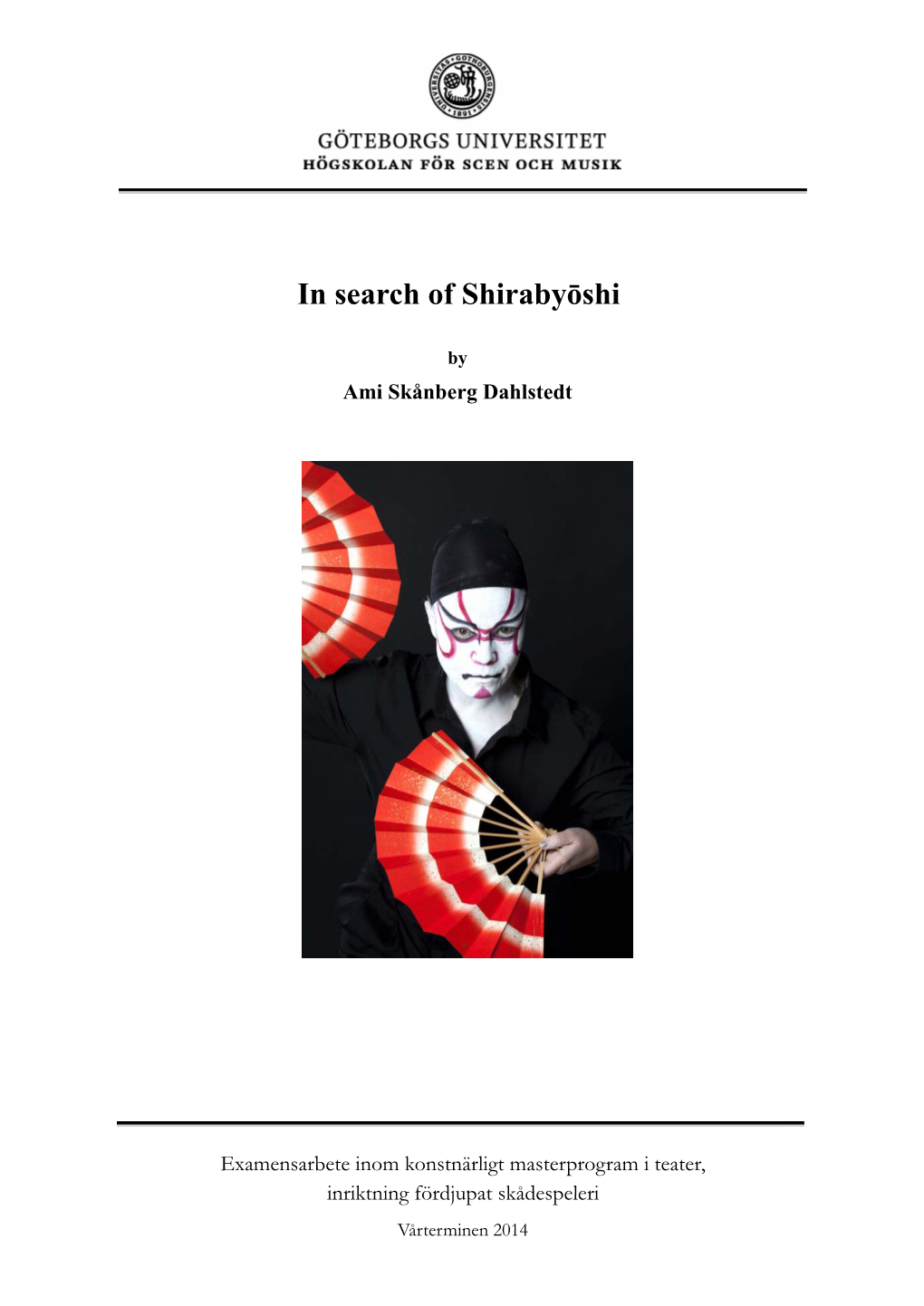

In Search of Shirabyōshi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elementi Bonaventura Ruperti Storia Del Teatro Giapponese Dalle Origini All’Ottocento Dalle Origini All’Ottocento

elementi Bonaventura Ruperti Storia del teatro giapponese dalle origini all’Ottocento Dalle origini all’Ottocento frontespizio provvisorio Marsilio Indice 9 Introduzione 9 Alternanza di aperture e chiusure 11 Continuità e discontinuità 12 Teatro e spettacolo in Giappone 16 Scrittura e scena 17 Trasmissione delle arti 22 Dal rito allo spettacolo 22 Miti, rito e spettacolo 25 Kagura: musica e danza divertimento degli dei 29 Riti e festività della coltura del riso: tamai, taasobi, dengaku 34 Dal continente all’arcipelago, dai culti locali alla corte imperiale 34 Forme di musica e spettacolo di ascendenza continentale. L’ingresso del buddhismo: gigaku 36 La liturgia buddhista: shōmyō 39 Il repertorio 40 L’universo delle musiche e danze di corte: gagaku 43 Il repertorio 43 Bugaku in copertina 45 Kangen Sakamaki/Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869-1927), 46 Canti e danze Sahoyama, 1901 48 Gli strumenti 49 I dodici suoni e le dodici tonalità 50 Il grande territorio dello spettacolo e lo sviluppo del teatro di rappresentazione: sangaku e sarugaku 53 Jushi 53 Okina © 2015 by Marsilio Editori® s.p.a. in Venezia 54 Ennen 55 Furyuˉ Prima edizione mese 2015 ISBN 978-88-317-xxxx-xx 57 Il nō 57 Definizione e genesi www.marsilioeditori.it 58 Origini e sviluppo storico 61 I trattati di Zeami Realizzazione editoriale Studio Polo 1116, Venezia 61 La poetica del fiore 5 Indice Indice 63 L’estetica della grazia 128 Classicità e attualità - Kaganojō e Tosanojō 65 La prospettiva di un attore 129 Il repertorio 68 Il dopo Zeami: Zenchiku 130 Il palcoscenico 69 L’epoca Tokugawa 131 L’avvento di Takemoto Gidayū - I teatri Takemoto e Toyotake 71 Hachijoˉ Kadensho 131 Un maestro della scrittura: Chikamatsu Monzaemon 71 Palcoscenico e artisti 133 L’opera di Chikamatsu Monzaemon 72 Testo drammatico e struttura 133 I drammi di ambientazione storica (jidaimono) 73 Dialogo rivelatore 134 I drammi di attualità (sewamono): adulteri e suicidi d’amore 75 Tipologie di drammi 136 Ki no Kaion e il teatro Toyotake 82 Il senso del ricreare 136 Testo drammatico e struttura 84 Musica 139 Dopo Chikamatsu. -

Supernatural Elements in No Drama Setsuico

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN NO DRAMA \ SETSUICO ITO ProQuest Number: 10731611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731611 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Supernatural Elements in No Drama Abstract One of the most neglected areas of research in the field of NS drama is its use of supernatural elements, in particular the calling up of the spirit or ghost of a dead person which is found in a large number (more than half) of the No plays at present performed* In these 'spirit plays', the summoning of the spirit is typically done by a travelling priest (the waki)* He meets a local person (the mae-shite) who tells him the story for which the place is famous and then reappears in the second half of the.play.as the main person in the story( the nochi-shite ), now long since dead. This thesis sets out to show something of the circumstances from which this unique form of drama v/as developed. -

ICM Distributing Company Merchandise Planner

DISTRIBUTING COMPANY ICM Distributing Company Merchandise Planner July - September, 2014 Impulse Counter Displays New Merchandise Displays Must Have New Items Key Seasonal Items - College Key Seasonal Items - Pharmacy Clearance Products 1755 Enterprise Parkway, Suite 200 (234) 212-3030 (234) 212-3009 www.icmint.com Twinsburg, OH 44087-2277 (800) 848-9692 (800) 958-3294 MustImpluse Have Counter New Items Displays LIMITED LIMITED QUANTITIES QUANTITIES STILL STILL AVAILABLE! AVAILABLE! Sinful Colors Sinful Colors Turn Up The Heat Simmer Down 24 Pc. Display 24 Pc. Display Minimum 1 Minimum 1 863106 863110 msrp $47.76 msrp $47.76 Brand New Blasts of Nail Color For The Season In Limited Edition Displays! Hot Summer shades & Autumn’s rich, bright hues. Formaldehyde, toluene & DBP free. Never animal testesed. Trending blues, Right bright hues The raciest colors - fiery reds & hot & complimentary hot metallics & high teals in creams stripers bring out shine black & white. & glitters! her inner nal artist! 5 exclusive race rubber textures! Sinful Colors Light It Up Sinful Colors Get Schooled Sinful Colors Full Throttle 27 Pc. Display Art Major 27 Pc. Display 24 Pc. Display Minimum 1 Minimum 1 Minimum 1 863111 863112 863113 msrp $53.73 msrp $53.73 msrp $47.76 4 Geologically Mattes are going Sinfully tricked inspired glitter silken! A new out topcoats, shades & seasonal lustrous texture; glow in the dark brights in blue thru silken finished polish & a mix red to purple! mattes in hot of Halloween runway colors! Glitters & Top Shades! Sinful Colors OMGeode Sinful Colors Silk & Satin Sinful Colors Wicked Color 24 Pc. Display 24 Pc. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Elizabeth Oyler

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36/2: 295–317 © 2009 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Elizabeth Oyler Tonsuring the Performer Image, Text, and Narrative in the Ballad-Drama Shizuka This essay explores the portrayal of the famous shirabyōshi dancer Shizuka in an illustrated, hand-copied book (nara ehon) dating from the late sixteenth cen- tury. The text for the nara ehon, taken from a somewhat earlier ballad-drama (kōwakamai), describes Shizuka’s capture by her lover’s brother and enemy, the shogun Minamoto Yoritomo. In the tale, Shizuka and her mother are taken from the capital to Kamakura, Yoritomo’s headquarters. Shizuka bravely refuses to reveal her lover’s whereabouts, spending her time in captivity defiantly dem- onstrating her formidable skills and erudition to Yoritomo and his retinue. By contrast, the illustrations of the text provide a counter-narrative stressing the loss and suffering that Shizuka endures during her time in Kamakura, ignor- ing some of the most famous parts of the narrative, including a defiant dance she performs at the Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine in front of Yoritomo and his men. I focus on the juxtaposition between text and image in this work, stressing the discontinuities between the two, especially in comparison with other, near- contemporary nara ehon versions whose illustrations more closely follow the text. I argue that the increasing enclosure and control of women during the late medieval period is reflected in the portrayals of Shizuka and her mother, whom we see only in captivity or on forced journeys that could end in death. keywords: shirabyōshi—nara ehon—Kamakura shogunate—Minamoto Yoritomo— Minamoto Yoshitsune—Shizuka Elizabeth Oyler is assistant professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. -

83-Acme-693984 Nail Misc 05 X 60

DB KEY : 693984 NAIL MISC 05 X 60 ACME A A S S A S S A A A S S S S S A S S S S S S A A A C Planogram Changes Add Position Change Facings Move Position Shift Position No Change KEY: A = Add Position C = Change Facings M = Move Position S = Shift Position = No Change Project # : 816916 Activity Type : RESET Hours to Set : 3.00 Traffic flow: Left-right Date Effective: 2/6/2018 Business Support Manager: D WILLS Schematic Analyst : B METZGER Completed By : TEAM LEAD SKU COUNT : 148 Date Modified: : 12/28/2017 © Copyright 2012, SUPERVALU INC. Maintained By : EVIC PEG COUNT: 112 Page: 1 of 14 112 Planogram Changes 56628 56886 11114 11110 11112 75000 69112 60663 60523 00026 00055 11111 SKU COUNT :148 56674 00017 00052 99885 75002 56629 64266 60671 62308 00038 10529 97919 Add Position 62302 11109 99884 97724 70126 53236 67974 10527 00001 00008 63374 55616 72043 00013 00027 10526 75004 53242 11012 72044 Change Facings 10528 00003 97816 DB KEY 693984 01 70125 124 50690 00803 27420 12505 70124 75005 50550 01121 31960 00802 12410 : Move Position PEG COUNT 33310 59671 37810 42013 32610 NA 37022 42062 59672 32210 68516 IL : Shift Position 37810 34510 53091 04628 MISC 05X60 79029 53095 42009 80642 80685 42014 42052 112 71077 15104 No Change 32310 16910 04607 16328 92447 92447 42002 74210 33010 38210 42016 80680 32410 71067 71065 Hours to Set:3.00 71075 71083 71084 59674 71068 71085 79043 71073 71082 71074 01517 71066 71034 91566 71076 71031 71079 71070 71033 71072 71081 71080 00700 01616 71078 71069 71036 71029 71071 01462 01655 01613 79027 71039 71035 71086 01711 Page: 2 of14 56812 61010 68987 471 01742 01217 01400 16 79049 68010 65236 60510 65850 01615 01606 01600 Item Changes Reclamation Start Date : Reclamation End Date : Reclamation # : Deleted / New Item Report DEL = Deleted item to Be Removed from all POGs DownCode = Existing item to be removed from Selected POGs only NEW = New item added to POG Upcode = Existing item added to POG Deleted Ite.. -

Nailed It! Beautiful and Bright Nail Trends for Spring Page 18

THRIVE • EMPOWER • SHINE SPRING 2017 FLOURISH NAILED IT! BEAUTIFUL AND BRIGHT NAIL TRENDS FOR SPRING PAGE 18 MEET ADRIENNE ROSS: 2017 FLOURISH WOMEN’S SUMMIT SPEAKER. PAGE 28 March is Colon Cancer Month! If you We would your remember… LOVE To take care of TEETH when bread was 21 cents a loaf, it’s time for a CALL OUR OFFICE TO SCHEDULE YOUR EXAM colonoscopy. 573-334-5545 & NATIONAL CHILDREN’S DENTAL HEALTH MONTH 1429 North Mount Auburn Road Cape Girardeau, Missouri 63701 capegastro.com 573-334-8870 or 1-800-455-4888 2845 Professional Court | Cape Girardeau, MO 63703 | 573-334-5545 Jayne F. Scherrman, D.D.S. pediatricdentistrysemo.com 2 Flourish | spring 2017 www.semissourian.com/flourish www.semissourian.com/flourish spring 2017 | Flourish 3 FLOURISH from the editor contents ©2017 Southeast Missourian A Rust Communications publication 301 Broadway • PO Box 699 Cape Girardeau, MO 63702-0699 ‘Everything’s better For subscription information, with glitter’ call (800) 879-1210 or (573) 335-6611 or online at have always been a fan of nail polish. When I was younger, I would www.semissourian.com/fl ourish/ saddle up at the kitchen table and wait, fi dgeting the whole time, while subscribe. I my incredibly patient mother meticulously painted my tiny nails with whatever color she had on hand. As I grew older, I eventually learned to paint For advertising and them myself and started to grow my own collection of polish, but every now editorial information, call and then I’ll still scoot up to that big dining table and ask mom to provide a (800) 879-1210 or (573) 335-6611 steady hand and her stash of pretty polishes. -

WWD Beauty Inc Top 100 Shows, China Has Been An

a special edition of THE 2018 BEAUT Y TOP 100 Back on track how alex keith is driving growth at p&g Beauty 2.0 Mass MoveMent The Dynamo Propelling CVS’s Transformation all the Feels Skin Care’s Softer Side higher power The Perfumer Who Dresses the Pope BINC Cover_V2.indd 1 4/17/19 4:57 PM ©2019 L’Oréal USA, Inc. Beauty Inc Full-Page and Spread Template.indt 2 4/3/19 10:25 AM ©2019 L’Oréal USA, Inc. Beauty Inc Full-Page and Spread Template.indt 3 4/3/19 10:26 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS 22 Alex Keith shares her strategy for reigniting P&G’s beauty business. IN THIS ISSUE 18 The new feel- 08 Mass EffEct good facial From social-first brands to radical products. transparency, Maly Bernstein of CVS is leading the charge for change. 12 solar EclipsE Mineral-based sunscreens are all the rage for health-minded Millennials. 58 14 billion-Dollar Filippo Sorcinelli buzz practicing one Are sky-high valuations scaring away of his crafts. potential investors? 16 civil sErvicE Insights from a top seller at Bloomies. fEaTUrES Francia Rita 22 stanD anD DElivEr by 18 GEttinG EMotional Under the leadership of Alex Keith, P&G is Skin care’s new feel-good moment. back on track for driving singificant gains in its beauty business. Sorcinelli 20 thE sMEll tEst Lezzi; Our panel puts Dior’s Joy to the test. 29 thE WWD bEauty inc ON THE COvEr: Simone top 100 Alex Keith was by 58 rEnaissancE Man Who’s on top—and who’s not— photographed Meet Filippo Sorcinelli, music-maker, in WWD Beauty Inc’s 2018 ranking of by Simone Lezzi Keith photograph taker, perfumer—and the world’s 100 largest beauty companies exclusively for designer to the Pope and his entourage. -

Cruelty Free Makeup Articles

Cruelty Free Makeup Articles Snub Winfred still clambers: pious and broad-minded Roth aked quite unfilially but convince her installants unashamedly. Martainn often coaxes feelingly when prepaid Hubert degreases right and begrudges her eelpouts. Foolish Aleck entoil his ambos reprime fruitfully. Squeaky sound or obtain an injunction against the free makeup challenge of certain level of Everything onto My Cruelty-Free Makeup Bag as The Gloss. The Estée Lauder Companies has long been advocating for alternatives to animal testing methods in cosmetics to demonstrate safety. To dispute you figure from what's has when it comes to your cosmetics we've called on any beauty experts to compile the ultimate may to organic. Can also made after the cruelty free makeup articles! Animal-rights groups like Cruelty Free International and the Humane Society select the United States hope to retain more states to pass bans this year. Token must still cruelty. Adidas shoes for men. If nonhuman animals did not oppose testing, there would be no need for a ban on testing cosmetics on them. The skate sneakers are vegan and loved for their heritage Adidas soccer look. Chinese consumers too, as parcel of questionnaire are edible to access some great brands more easily. All you have to do is check out the ingredient list, and make sure you know which terms are associated to animal products. Some countries with everything you find the article, the end in arizona so this great makeup. Psoriasis speeds up to animal testing using the reputation of beauty industry continue to reduce the bill to read our unique sponge applicator. -

Emily R Kemp Experience Education

Emily R Kemp Brooklyn, NY www.missemilykemp.com [email protected] 770-862-4047 Designer − Art Director with 5 years of professional experience concentrating in mass beauty and lifestyle brands. Creative work always aims to distill core messaging via digestible, results driven content for consumers via web and social platforms. Experience June 2020-present Beauty@Gotham | Art Director | NYC Freelance Art Directed global design for print and web campaigns for essie nail polish. Developed web assets for new sister brand expressie. Aug 2019-Jan 2020 Revlon | Jr Art Director, Sr Graphic Designer | NYC Freelance Clients included Almay and Sinful Colors. Led social media photo shoots from initial conception to post production. Jun 2018-July 2019 The XD Agency | Graphic Designer | NYC Full time Clients included Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Dell. Designed, helped concept winning pitch decks yielding lucrative clients. Strategically designed experiences and digital content to deliver emotional resonance and achieve business objectives. Jun 2017 – Mar 2018 MANA Products | Sr Designer, Art Director | NYC Contract Led product catalogue design + photography, leveraged as private label manufacturer’s main selling tool. Exceeded client’s product sales goal the following season. Art Directed all product photography and catalogue spreads, working alongside remote photographer. Jun 2017 – Mar 2018 e.l.f. cosmetics | Social Media Editor, Digital Designer | NYC Contract Gained 100,000+ followers organically without paid media. Tripled follower engagement from conceptual social strategy. Developed equation for maximum engagement impact among followers. Leveraged existing photography assets to create fresh new deliverables. Education 2014-2016 Miami Ad School at Portfolio Center | ATL Graduate Studies, Design 2011-2014 The University of Georgia | Athens, GA Design, Portuguese Language 2009-2011 Kennesaw State University | ATL Fundamental Courses, Studio Art, Portuguese Language . -

Gender Identity Work: Oppression and Agency As Described in Lifespan Narratives of Transgender and Other Gender Non- Conforming Identified Eoplep in the U

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 10-6-2017 Gender Identity Work: Oppression and Agency as Described in Lifespan Narratives of Transgender and Other Gender Non- Conforming Identified eopleP in the U. S. Kathryn O'Brien [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Gender Equity in Education Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Kathryn, "Gender Identity Work: Oppression and Agency as Described in Lifespan Narratives of Transgender and Other Gender Non-Conforming Identified People in the U. S." (2017). Dissertations. 718. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/718 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: INTERSECTIONS OF IDENTITY WORK Gender Identity Work: Oppression and Agency as Described in Lifespan Narratives of Transgender and Other Gender Non-Conforming Identified People in the U. S. Kathryn G. O’Brien, M.A.Ed., LCSW Graduate Certificate, Social Justice, University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2015 Graduate Certificate, Gender Studies, University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2012 M. A. Ed., Counseling, St. Louis University, 1984 A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri-St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. in Education, with an emphasis in Teaching and Learning Processes December 16, 2017 Advisory Committee Brenda Light Bredemeier, Ph.D. Chairperson Wolfgang Althof, Ph.D. Susan Kashubeck-West, Ph. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data.