Full Disclosure Form Information Provided by the Authors Is Available with the Full Text of This Article at Neurology.Org/NN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Genomics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ygeno Whole-genome comparison clarifies close phylogenetic relationships between the phyla Dictyoglomi and Thermotogae Hiromi Nishida a,⁎, Teruhiko Beppu b, Kenji Ueda b a Agricultural Bioinformatics Research Unit, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo, 1-1-1 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan b Life Science Research Center, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, Fujisawa, Japan article info abstract Article history: The anaerobic thermophilic bacterial genus Dictyoglomus is characterized by the ability to produce useful Received 2 June 2011 enzymes such as amylase, mannanase, and xylanase. Despite the significance, the phylogenetic position of Accepted 1 August 2011 Dictyoglomus has not yet been clarified, since it exhibits ambiguous phylogenetic positions in a single gene Available online 7 August 2011 sequence comparison-based analysis. The number of substitutions at the diverging point of Dictyoglomus is insufficient to show the relationships in a single gene comparison-based analysis. Hence, we studied its Keywords: evolutionary trait based on whole-genome comparison. Both gene content and orthologous protein sequence Whole-genome comparison Dictyoglomus comparisons indicated that Dictyoglomus is most closely related to the phylum Thermotogae and it forms a Bacterial systematics monophyletic group with Coprothermobacter proteolyticus (a constituent of the phylum Firmicutes) and Coprothermobacter proteolyticus Thermotogae. Our findings indicate that C. proteolyticus does not belong to the phylum Firmicutes and that the Thermotogae phylum Dictyoglomi is not closely related to either the phylum Firmicutes or Synergistetes but to the phylum Thermotogae. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. -

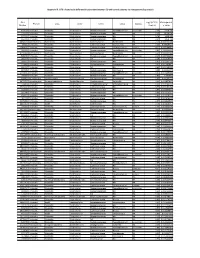

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Analyzing the Early Stages of Clostridium Difficile Spore

ANALYZING THE EARLY STAGES OF CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE SPORE GERMINATION A Dissertation by MICHAEL FRANCIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Joseph A. Sorg Committee Members, James L. Smith Matthew S. Sachs Paul D. Straight Head of Department, Thomas D. McKnight May 2017 Major Subject: Microbiology Copyright 2017 Michael Francis ABSTRACT Infections caused by Clostridium difficile have increased steadily over the past several years. While studies on C. difficile virulence and physiology have been hindered, in the past, by lack of genetic approaches and suitable animal models, newly developed technologies and animal models allow for improved experimental detail. One such advance was the generation of a mouse-model of C. difficile infection. This system was an important step forward in the analysis of the genetic requirements for colonization and infection. Equally important is understanding the differences that exist between mice and humans. One of these differences is the natural bile acid composition. Bile acid-mediated spore germination, a process whereby a dormant spore returns to active, vegetative growth, is an important step during C. difficile colonization. Mice produce several different bile acids that are not found in humans (muricholic acids) that have the potential to impact C. difficile spore germination. In order to understand potential effects of these different bile acids on C. difficile physiology, we characterized their effects on C. difficile spore germination and growth of vegetative cells. We found that the mouse-derived muricholic acids affect germination similarly to a previously-described inhibitor of germination, chenodeoxycholic acid. -

Table S4. Phylogenetic Distribution of Bacterial and Archaea Genomes in Groups A, B, C, D, and X

Table S4. Phylogenetic distribution of bacterial and archaea genomes in groups A, B, C, D, and X. Group A a: Total number of genomes in the taxon b: Number of group A genomes in the taxon c: Percentage of group A genomes in the taxon a b c cellular organisms 5007 2974 59.4 |__ Bacteria 4769 2935 61.5 | |__ Proteobacteria 1854 1570 84.7 | | |__ Gammaproteobacteria 711 631 88.7 | | | |__ Enterobacterales 112 97 86.6 | | | | |__ Enterobacteriaceae 41 32 78.0 | | | | | |__ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae 13 7 53.8 | | | | |__ Erwiniaceae 30 28 93.3 | | | | | |__ Erwinia 10 10 100.0 | | | | | |__ Buchnera 8 8 100.0 | | | | | | |__ Buchnera aphidicola 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pantoea 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Yersiniaceae 14 14 100.0 | | | | | |__ Serratia 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Morganellaceae 13 10 76.9 | | | | |__ Pectobacteriaceae 8 8 100.0 | | | |__ Alteromonadales 94 94 100.0 | | | | |__ Alteromonadaceae 34 34 100.0 | | | | | |__ Marinobacter 12 12 100.0 | | | | |__ Shewanellaceae 17 17 100.0 | | | | | |__ Shewanella 17 17 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonadaceae 16 16 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonas 15 15 100.0 | | | | |__ Idiomarinaceae 9 9 100.0 | | | | | |__ Idiomarina 9 9 100.0 | | | | |__ Colwelliaceae 6 6 100.0 | | | |__ Pseudomonadales 81 81 100.0 | | | | |__ Moraxellaceae 41 41 100.0 | | | | | |__ Acinetobacter 25 25 100.0 | | | | | |__ Psychrobacter 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Moraxella 6 6 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudomonadaceae 40 40 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudomonas 38 38 100.0 | | | |__ Oceanospirillales 73 72 98.6 | | | | |__ Oceanospirillaceae -

Resilience of Microbial Communities After Hydrogen Peroxide Treatment of a Eutrophic Lake to Suppress Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms

microorganisms Article Resilience of Microbial Communities after Hydrogen Peroxide Treatment of a Eutrophic Lake to Suppress Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms Tim Piel 1,†, Giovanni Sandrini 1,†,‡, Gerard Muyzer 1 , Corina P. D. Brussaard 1,2 , Pieter C. Slot 1, Maria J. van Herk 1, Jef Huisman 1 and Petra M. Visser 1,* 1 Department of Freshwater and Marine Ecology, Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, 1090 GE Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] (T.P.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (C.P.D.B.); [email protected] (P.C.S.); [email protected] (M.J.v.H.); [email protected] (J.H.) 2 Department of Marine Microbiology and Biogeochemistry, NIOZ Royal Netherland Institute for Sea Research, 1790 AB Den Burg, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +31-20-5257073 † These authors have contributed equally to this work. ‡ Current address: Department of Technology & Sources, Evides Water Company, 3006 AL Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Abstract: Applying low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to lakes is an emerging method to mitigate harmful cyanobacterial blooms. While cyanobacteria are very sensitive to H2O2, little Citation: Piel, T.; Sandrini, G.; is known about the impacts of these H2O2 treatments on other members of the microbial com- Muyzer, G.; Brussaard, C.P.D.; Slot, munity. In this study, we investigated changes in microbial community composition during two P.C.; van Herk, M.J.; Huisman, J.; −1 lake treatments with low H2O2 concentrations (target: 2.5 mg L ) and in two series of controlled Visser, P.M. -

Lung Microbiota Predict Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis and Its Outcome in Immunocompromised Patients

Respiratory infection Original research Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216179 on 25 June 2021. Downloaded from Lung microbiota predict invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and its outcome in immunocompromised patients Anaïs Hérivaux,1,2 Jesse R Willis,3,4 Toine Mercier,5,6 Katrien Lagrou,6,7 Samuel M Gonçalves,1,2 Relber A Gonçales,1,2 Johan Maertens,5,6 Agostinho Carvalho,1,2 Toni Gabaldón,3,4,8 Cristina Cunha 1,2 ► Additional supplemental ABStract material is published online Rationale Recent studies have revealed that the lung Key messages only. To view, please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. microbiota of critically ill patients is altered and predicts org/ 10. 1136/ thoraxjnl- 2020- clinical outcomes. The incidence of invasive fungal What is the key question? 216179). infections, namely, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis ► Does the lung microbiota modulate (IPA), in immunocompromised patients is increasing, but susceptibility to invasive pulmonary For numbered affiliations see the clinical significance of variations in lung bacterial aspergillosis (IPA) and predict its clinical end of article. communities is unknown. outcome? Objectives To define the contribution of the lung Correspondence to What is the bottom line? microbiota to the development and course of IPA. Dr Cristina Cunha, Life and ► We show that variation in the lung microbiota Health Sciences Research Methods and measurements We performed an is associated with the development of IPA in Institute (ICVS), University observational cohort study to characterise the lung critically ill patients. Patients with IPA display of Minho, Braga 4710-057, microbiota in 104 immunocompromised patients using Portugal; a microbiota signature in the lower airways bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing on cristinacunha@ med. -

Significance of Donor Human Milk

fmicb-09-01376 June 26, 2018 Time: 17:31 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 27 June 2018 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01376 Preterm Gut Microbiome Depending on Feeding Type: Significance of Donor Human Milk Anna Parra-Llorca1, María Gormaz1,2, Cristina Alcántara3, María Cernada1,2, Antonio Nuñez-Ramiro1,2, Máximo Vento1,2*† and Maria C. Collado3*† 1 Neonatal Research Group, Health Research Institute La Fe, University and Polytechnic Hospital La Fe, Valencia, Spain, 2 Division of Neonatology, University and Polytechnic Hospital La Fe, Valencia, Spain, 3 Department of Biotechnology, Institute of Agrochemistry and Food Technology, Spanish National Research Council, Valencia, Spain Preterm microbial colonization is affected by gestational age, antibiotic treatment, type of birth, but also by type of feeding. Breast milk has been acknowledged as the gold standard for human nutrition. In preterm infants breast milk has been associated with improved growth and cognitive development and a reduced risk of necrotizing enterocolitis and late onset sepsis. In the absence of their mother’s own milk (MOM), pasteurized donor human milk (DHM) could be the best available alternative due to its similarity to the former. However, little is known about the effect of DHM upon preterm Edited by: Sandra Torriani, microbiota and potential biological implications. Our objective was to determine the University of Verona, Italy impact of DHM upon preterm gut microbiota admitted in a referral neonatal intensive Reviewed by: care unit (NICU). A prospective observational cohort study in NICU of 69 neonates Carlotta De Filippo, <32 weeks of gestation and with a birth weight ≤1,500 g was conducted. -

Unexpected Diversity During Community Succession in the Apple Flower Microbiome

RESEARCH ARTICLE Unexpected Diversity during Community Succession in the Apple Flower Microbiome Ashley Shade,a Patricia S. McManus,b Jo Handelsmana Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USAa; Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin— Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USAb ABSTRACT Despite its importance to the host, the flower microbiome is poorly understood. We report a culture-independent, community-level assessment of apple flower microbial diversity and dynamics. We collected flowers from six apple trees at five time points, starting before flowers opened and ending at petal fall. We applied streptomycin to half of the trees when flowers opened. Assessment of microbial diversity using tag pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA genes revealed that the apple flower communi- ties were rich and diverse and dominated by members of TM7 and Deinococcus-Thermus, phyla about which relatively little is known. From thousands of taxa, we identified six successional groups with coherent dynamics whose abundances peaked at dif- ferent times before and after bud opening. We designated the groups Pioneer, Early, Mid, Late, Climax, and Generalist commu- nities. The successional pattern was attributed to a set of prevalent taxa that were persistent and gradually changing in abun- dance. These taxa had significant associations with other community members, as demonstrated with a cooccurrence network based on local similarity analysis. We also detected a set of less-abundant, transient taxa that contributed to general tree-to-tree variability but not to the successional pattern. Communities on trees sprayed with streptomycin had slightly lower phylogenetic diversity than those on unsprayed trees but did not differ in structure or succession. -

Clostridioides Difficileinfections

bioMérieux In vitro diagnostics serving CLOSTRIDIOIDES public health DIFFICILE INFECTIONS A major player in in vitro diagnostics for more than 50 years, From Diagnosis to bioMérieux has always been driven by a pioneering spirit and unrelenting commitment to improve public health worldwide. Outbreak Management Our diagnostic solutions bring high medical value to healthcare professionals, providing them with the most relevant and reliable information, as quickly as possible, to support treatment decisions and better patient care. bioMérieux’s mission entails a commitment to support medical education, by promoting access to diagnostic knowledge for as many people as possible. Focusing on the medical value of diagnostics, our collection of educational booklets aims to raise awareness of the essential role that diagnostic test results play in healthcare decisions. Other educational booklets are available. Consult your local bioMérieux representative. The information in this booklet is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be exhaustive. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a medical director, physician, or other qualified health provider regarding processes and/or protocols for diagnosis and treatment of a medical condition. bioMérieux assumes no responsibility or liability for any diagnosis established or treatment prescribed by the physician. bioMérieux, Inc. • 100 Rodolphe Street • Durham, NC 27712 • USA • Tel: (800) 682 2666 • Fax: (800) 968 9494 © 2019 bioMérieux, Inc. • BIOMERIEUX and the BIOMERIEUX logo, are used pending and/or registered trademarks belonging to bioMérieux, or one of its subsidiaries, or one of its companies. companies. its or one of subsidiaries, its or one of bioMérieux, belonging to trademarks registered pending and/or used are logo, and the BIOMERIEUX • BIOMERIEUX Inc. -

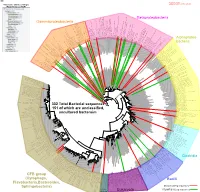

Bacteria Clostridia Bacilli Eukaryota CFB Group

AM935842.1.1361 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY283260.1.1552 Alcaligenes sp. PCNB−2 Class Betaproteobacteria AM934953.1.1374 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581593.1.1460 uncultured betaAM936569.1.1351 proteobacterium uncultured Class Betaproteobacteria Derxia sp. Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581621.1.1418 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ248272.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium soil uncultured DQ248272.1.1498 DQ248235.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium RS49 DQ248270.1.1496 uncultured soil bacterium DQ256489.1.1211 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax DQ256489.1.1211 AF523053.1.1486 uncultured Comamonadaceae bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY706442.1.1396 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY706442.1.1396 AJ536763.1.1422 uncultured bacterium CS000359.1.1530 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax CS000359.1.1530 AY168733.1.1411 uncultured bacterium AJ009470.1.1526 uncultured bacterium SJA−62 Class Betaproteobacteria Class SJA−62 bacterium uncultured AJ009470.1.1526 AY212561.1.1433 uncultured bacterium D16212.1.1457 Rhodoferax fermentans Class Betaproteobacteria Class fermentans Rhodoferax D16212.1.1457 AY957894.1.1546 uncultured bacterium AJ581620.1.1452 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria RS76 AY625146.1.1498 uncultured bacterium RS65 DQ316832.1.1269 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ404909.1.1513 uncultured bacterium uncultured DQ404909.1.1513 AB021341.1.1466 bacterium rM6 AJ487020.1.1500 uncultured bacterium uncultured AJ487020.1.1500 RS7 RS86RC AF364862.1.1425 bacterium BA128 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957931.1.1529 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957931.1.1529 CP000884.723807.725332 Delftia acidovorans SPH−1 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957923.1.1520 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957923.1.1520 RS18 AY957918.1.1527 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957918.1.1527 AY945883.1.1500 uncultured bacterium AF526940.1.1489 uncultured Ralstonia sp. -

Exploring the Diversity and Antimicrobial Potential of Marine Actinobacteria from the Comau Fjord in Northern Patagonia, Chile

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 19 July 2016 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01135 Exploring the Diversity and Antimicrobial Potential of Marine Actinobacteria from the Comau Fjord in Northern Patagonia, Chile Agustina Undabarrena 1, Fabrizio Beltrametti 2, Fernanda P. Claverías 1, Myriam González 1, Edward R. B. Moore 3, 4, Michael Seeger 1 and Beatriz Cámara 1* 1 Laboratorio de Microbiología Molecular y Biotecnología Ambiental, Departamento de Química & Centro de Biotecnología Daniel Alkalay Lowitt, Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, Valparaíso, Chile, 2 Actygea S.r.l., Gerenzano, Italy, 3 Culture Collection University of Gothenburg (CCUG), Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 4 Department of Infectious Diseases, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Edited by: Bioprospecting natural products in marine bacteria from fjord environments are attractive Learn-Han Lee, due to their unique geographical features. Although, Actinobacteria are well known Monash University Malaysia Campus, Malaysia for producing a myriad of bioactive compounds, investigations regarding fjord-derived Reviewed by: marine Actinobacteria are scarce. In this study, the diversity and biotechnological Atte Von Wright, potential of Actinobacteria isolated from marine sediments within the Comau University of Eastern Finland, Finland fjord, in Northern Chilean Patagonia, were assessed by culture-based approaches. Polpass Arul Jose, Central Salt and Marine Chemicals The 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed that members phylogenetically related Research Institute, India to the Micrococcaceae, Dermabacteraceae, Brevibacteriaceae, Corynebacteriaceae, *Correspondence: Microbacteriaceae, Dietziaceae, Nocardiaceae, and Streptomycetaceae families were Beatriz Cámara [email protected] present at the Comau fjord. A high diversity of cultivable Actinobacteria (10 genera) was retrieved by using only five different isolation media. -

Gut Microbiota Differs in Composition and Functionality Between Children

Diabetes Care Volume 41, November 2018 2385 Gut Microbiota Differs in Isabel Leiva-Gea,1 Lidia Sanchez-Alcoholado,´ 2 Composition and Functionality Beatriz Mart´ın-Tejedor,1 Daniel Castellano-Castillo,2,3 Between Children With Type 1 Isabel Moreno-Indias,2,3 Antonio Urda-Cardona,1 Diabetes and MODY2 and Healthy Francisco J. Tinahones,2,3 Jose´ Carlos Fernandez-Garc´ ´ıa,2,3 and Control Subjects: A Case-Control Mar´ıa Isabel Queipo-Ortuno~ 2,3 Study Diabetes Care 2018;41:2385–2395 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0253 OBJECTIVE Type 1 diabetes is associated with compositional differences in gut microbiota. To date, no microbiome studies have been performed in maturity-onset diabetes of the young 2 (MODY2), a monogenic cause of diabetes. Gut microbiota of type 1 diabetes, MODY2, and healthy control subjects was compared. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/COMPLICATIONS RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS This was a case-control study in 15 children with type 1 diabetes, 15 children with MODY2, and 13 healthy children. Metabolic control and potential factors mod- ifying gut microbiota were controlled. Microbiome composition was determined by 16S rRNA pyrosequencing. 1Pediatric Endocrinology, Hospital Materno- Infantil, Malaga,´ Spain RESULTS 2Clinical Management Unit of Endocrinology and Compared with healthy control subjects, type 1 diabetes was associated with a Nutrition, Laboratory of the Biomedical Research significantly lower microbiota diversity, a significantly higher relative abundance of Institute of Malaga,´ Virgen de la Victoria Uni- Bacteroides Ruminococcus Veillonella Blautia Streptococcus versityHospital,Universidad de Malaga,M´ alaga,´ , , , , and genera, and a Spain lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and 3Centro de Investigacion´ BiomedicaenRed(CIBER)´ Lachnospira.