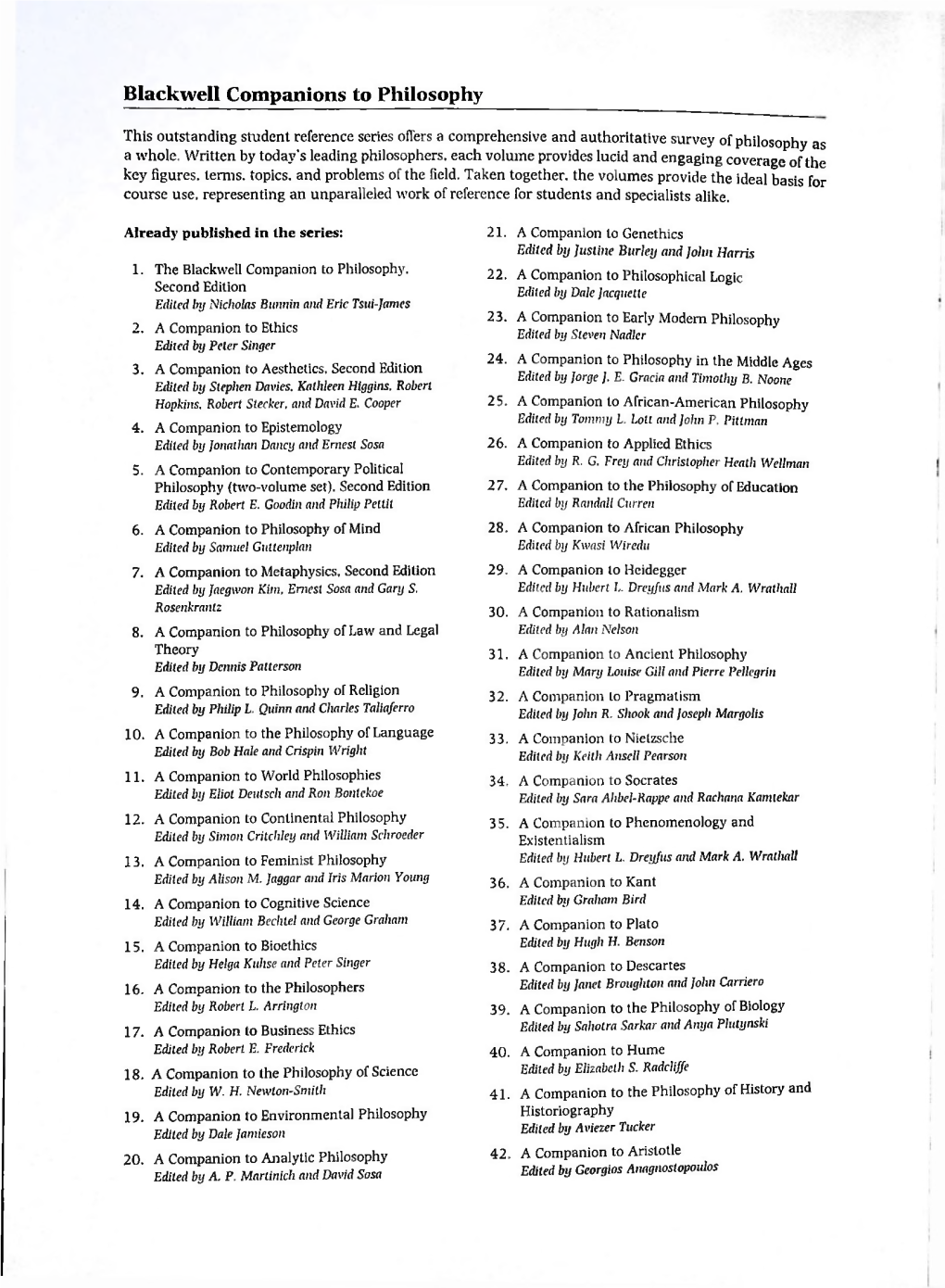

Blackwell Companions to Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Williamson and Simplicity in Modal Logic∗ Theodore Sider Canadian Journal of Philosophy 46 (2016): 683–98

On Williamson and Simplicity in Modal Logic∗ Theodore Sider Canadian Journal of Philosophy 46 (2016): 683–98 According to Timothy Williamson, we should accept the simplest and most powerful second-order modal logic, and as a result accept an ontology of “bare possibilia”. This general method for extracting ontology from logic is salutary, but its application in this case depends on a questionable assumption: that modality is a fundamental feature of the world. 1. Necessitism The central thesis of Williamson’s wonderful book Modal Logic as Metaphysics is “Necessitism”. Put roughly and vividly, Necessitism says that everything neces- sarily exists. Williamson himself avoids the predicate ‘exists’, and formulates the view thus: Necessitism x2 y y = x (“Everything necessarily is something”) 8 9 Williamson’s scruples about ‘exists’ are reasonable but sometimes require tor- tured prose, so, choosing beauty over function, I will use the E-word. (But let it be understood that by “x exists” I just mean that x is identical to something— with quanti ers “wide open”.) The considerations favoring Necessitism also lead Williamson to accept the Barcan schema (as well as its converse): Barcan schema 3 xA x3A 9 ! 9 So if there could have been a child of Wittgenstein, then there in fact exists something that could have been a child of Wittgenstein. This thing that could have been a child of Wittgenstein: what is it like? What are its properties? Well, it has the modal property of possibly being a child of Wittgenstein. And logic demands that it have certain further properties, such as the property of being self-identical, the property of being green if it is green, and so forth. -

A Companion to the Philosophy of Language

A COMPANION TO THE PHILOSOPHY OF LANGUAGE SECOND EDITION Volume I Edited by Bob Hale, Crispin Wright, and Alexander Miller This second edition first published 2017 © 2017 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. (1e, 1997) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of Bob Hale, Crispin Wright, and Alexander Miller to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks, or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Logic, Essence, and Modality Introduction 1 Hale's

Logic, Essence, and Modality A Critical Review of Bob Hale’s Necessary Beings Christopher Menzel∗ Bob Hale, Necessary Beings: An Essay on Ontology, Modality, and the Relations Between Them. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-966957-8 (hbk). Pp. ix + 298. Introduction Bob Hale’s distinguished record of research places him among the most important and influential contemporary analytic metaphysicians. In his deep, wide ranging, yet highly readable book Necessary Beings, Hale draws upon, but substantially integrates and ex- tends, a good deal his past research to produce a sustained and richly textured essay on — as promised in the subtitle — ontology, modality, and the relations between them. I’ve set myself two tasks in this review: first, to provide a reasonably thorough (if not exactly comprehensive) overview of the structure and content of Hale’s book and, second, to a limited extent, to engage Hale’s book philosophically. I approach these tasks more or less sequentially: Parts I and 2 of the review are primarily expository; in Part 3 I adopt a some- what more critical stance and raise several issues concerning one of the central elements of Hale’s account, his essentialist theory of modality. 1 Hale’s Basic Ontology and Its Logic Hale’s Ontology Unsurprisingly in a book on necessary beings, Hale begins his study by addressing “the central question of ontology” (p. 9), namely: What kinds of things there?1 His answer (developed and defended in 1.2-1.6) is “broadly Fregean”, both methodologically and xx ∗This review is scheduled to appear in the October 2015 edition of Philosophia Mathematica, which is pub- lished by Oxford University Press. -

PHS Volume 51 Cover and Front Matter

Supplement to 'Philosophy' ' Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement: 51 Logic, Thought and Language Edited by Anthony O'Hear Contributors Bob Hale, M. G. F. Martin, Gregory McCulloch, Alan Millar, A. W. Moore, Christopher Peacocke, R. M. Sainsbury, Gabriel M. A. Segal, Scott Sturgeon, Julia Tanney, Charles Travis, S. G. Williams, Timothy Williamson, Crispin Wright Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 29 Sep 2021 at 21:39:07, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1358246100008018 Logic, Thought and Language ROYAL INSTITUTE OF PHILOSOPHY SUPPLEMENT: 51 EDITED BY Anthony O'Hear CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 29 Sep 2021 at 21:39:07, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1358246100008018 PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, CB2 1RP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia © The Royal Institute of Philosophy and the contributors 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset by Michael Heath Ltd, Reigate, Surrey A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 521 52966 2 paperback ISSN 1358-2461 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

From: Companion to the Philosophy of Language, Crispin Wright and Bob Hale, Eds., (Blackwell, 1995)

From: Companion to the Philosophy of Language, Crispin Wright and Bob Hale, eds., (Blackwell, 1995) METAPHOR Richard Moran Metaphor enters contemporary philosophical discussion from a variety of directions. Aside from its obvious importance in poetics, rhetoric, and aesthetics, it also figures in such fields as philosophy of mind (e.g., the question of the metaphorical status of ordinary mental concepts), philosophy of science (e.g, the comparison of metaphors and explanatory models), in epistemology (e.g., analogical reasoning), and in cognitive studies (in, e.g., the theory of concept-formation). This article will concentrate on issues metaphor raises for the philosophy of language, with the understanding that the issues in these various fields cannot be wholly isolated from each other. Metaphor is an issue for the philosophy of language not only for its own sake, as a linguistic phenomenon deserving of analysis and interpretation, but also for the light it sheds on non-figurative language, the domain of the literal which is the normal preoccupation of the philosopher of language. A poor reason for this preoccupation would be the assumption that purely literal language is what most language-use consists in, with metaphor and the like sharing the relative infrequency and marginal status of songs or riddles. This would not be a good reason not only because mere frequency is not a good guide to theoretical importance, but also because it is doubtful that the assumption is even true. In recent years, writers with very different concerns have pointed out that figurative language of one sort or another is a staple of the most common as well as the most specialized speech, as the brief list of directions of interest leading to metaphor would suggest. -

Curriculum Vitæ JOHN PATTON BURGESS

Curriculum Vitæ JOHN PATTON BURGESS PERSONAL DATA Date of Birth 5 June, 1948 Place of Birth Berea, Ohio, USA Citizenship USA Office Address Department of Philosophy Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006 USA Office Telephone/ Voice Mail (609)-258-4310 e-mail address [email protected] website www.princeton.edu/~jburgess ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY 2009- John N. Woodhull Professor of Philosophy 1986-2009 Professor 1981-1986 Associate Professor 1975-1981 Assistant Professor UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN AT MADISON DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS 1974-75 Post-Doctoral Instructor HIGHER EDUCATION 1970-1974 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY 1974 PH.D. IN LOGIC & METHODOLOGY Dissertation: Infinitary Languages & Descriptive Set Theory Supervisor: Jack H. Silver 1969-1970 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY 1970 M. S. IN MATHEMATICS Thesis: Obstacles to Embedding 4-Manifolds Supervisor: Henry H. Glover 1966-1969 PRINCETON UNIVERSITY 1969 A.B. IN MATHEMATICS (summa cum laude, FBK) Thesis: Probability Logic Advisor: Simon B. Kochen EDITORIAL AND RELATED ACTIVITIES F.O.M. [Foundations of Mathematics Moderated Electronic Discussion Board] 2010- Member, Editorial Board TEMPLETON FOUNDATION 2008 Juror, Gödel Centenary Research Prize Fellowships 2007 Juror, Exploring the Infinite, Phase I: Mathematics and Mathematical Logic PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES 2006- Consulting Editor MACMILLAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF PHILOSOPHY, 2ND ED. 2004-06 Consulting Editor for Logic ASSOCIATION FOR SYMBOLIC LOGIC 2008- Memeber of Editorial Board for Reviews, -

Nominalism and the Contingency of Abstract Objects Crispin Wright; Bob Hale the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Nominalism and the Contingency of Abstract Objects Crispin Wright; Bob Hale The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 89, No. 3. (Mar., 1992), pp. 111-135. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-362X%28199203%2989%3A3%3C111%3ANATCOA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z The Journal of Philosophy is currently published by Journal of Philosophy, Inc.. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/jphil.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to and preserving a digital archive of scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Jun 17 04:56:44 2007 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY NOMINALISM AND THE CONTINGENCY OF ABSTRACT OBJECTS* RADITIONAL mathematical nominalism1 regards a mathe- matical theory as acceptable only if it can be so interpreted Tas to involve no purported quantification over or singular reference to abstract objects. -

A Guide to Naturalizing Semantics

8 A Guide to Naturalizing Semantics BARRY LOEWER Semantic predicates – is true, refers, is about, has the truth‐conditional content that p – are applicable both to natural‐language expressions and to mental states. For example, both the sentence “The cat is crying” and the belief that the cat is crying are about the cat and pos sess the truth‐conditional content that the cat is crying. It is widely thought that the semantic properties of natural‐language expressions are derived from the semantic pro perties of men tal states.1 According to one version of this view, the sentence “The cat is crying” obtains its truth‐conditions from conventions governing its use, especially its being used to express the thought that the cat is crying. These conventions are themselves explained in terms of the beliefs, intentions, and so forth of English speakers.2 In the following I will assume that some such view is correct and concentrate on the semantic properties of mental states.3 In virtue of what do mental states possess their semantic properties? What makes it the case that a particular mental state is about the cat and has the truth‐conditions that the cat is crying? The answer cannot be the same as for natural‐language expressions, since the conventions that ground the latter’s semantic properties are explained in terms of the semantic properties of mental states. If there is an answer, that is, if semantic properties are real and are not fundamental, then it must be that they are instantiated in virtue of the instantiation of certain non‐semantic properties. -

The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Abstraction*

THE METAPHYSICS AND EPISTEMOLOGY OF ABSTRACTION* CRISPIN WRIGHT University of St. Andrews & New York University 1 Paul Benacerraf famously wondered1 how any satisfactory account of mathematical knowledge could combine a face-value semantic construal of classical mathematical theories, such as arithmetic, analysis and set-the- ory – one which takes seriously the apparent singular terms and quantifiers in the standard formulations – with a sensibly naturalistic conception of our knowledge-acquisitive capacities as essentially operative within and subject to the domain of causal law. The problem, very simply, is that the entities apparently called for by the face-value construal – finite cardinals, reals and sets – do not, seemingly, participate in the causal swim. A re- finement of the problem, due to Field, challenges us to explain what reason there is to suppose that our basic beliefs about such entities, encoded in standard axioms, could possibly be formed reliably by means solely of what are presumably naturalistic belief-forming mechanisms. These prob- lems have cast a long shadow over recent thought about the epistemology of mathematics. Although ultimately Fregean in inspiration, Abstractionism – often termed ‘neo-Fregeanism’ – was developed with the goal of responding to them firmly in view. The response is organised under the aegis of a kind of linguistic – better, propositional – ‘turn’ which I suggest it is helpful to see as part of the content of Frege’s Context Principle. The turn is this. It is not that, before we can understand how knowledge is possible of statements re- ferring to or quantifying over the abstract objects of mathematics, we need to understand how such objects can be given to us as objects of acquaint- ance or how some other belief-forming mechanisms might be sensitive to them and their characteristics. -

L-G-0009564422-0018336699.Pdf

A Companion to the Philosophy of Language Blackwell Companions to Philosophy This outstanding student reference series offers a the key figures, terms, topics, and problems of the field. comprehensive and authoritative survey of philosophy Taken together, the volumes provide the ideal basis as a whole. Written by today’s leading philosophers, for course use, representing an unparalleled work of each volume provides lucid and engaging coverage of reference for students and specialists alike. Already published in the series: 1. The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, Second Edition 33. A Companion to Nietzsche Edited by Nicholas Bunnin and Eric Tsui‐James Edited by Keith Ansell Pearson 2. A Companion to Ethics 34. A Companion to Socrates Edited by Peter Singer Edited by Sara Ahbel‐Rappe and Rachana Kamtekar 3. A Companion to Aesthetics, Second Edition 35. A Companion to Phenomenology and Existentialism Edited by Stephen Davies, Kathleen Marie Higgins, Robert Hopkins, Edited by Hubert L. Dreyfus and Mark A. Wrathall Robert Stecker, and David E. Cooper 36. A Companion to Kant 4. A Companion to Epistemology, Second Edition Edited by Graham Bird Edited by Jonathan Dancy, Ernest Sosa, and Matthias Steup 37. A Companion to Plato 5. A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy (two‐volume Edited by Hugh H. Benson set), Second Edition 38. A Companion to Descartes Edited by Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit Edited by Janet Broughton and John Carriero 6. A Companion to Philosophy of Mind 39. A Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by Samuel Guttenplan Edited by Sahotra Sarkar and Anya Plutynski 7. A Companion to Metaphysics, Second Edition 40. -

FIL2405/FIL4405 – Philosophical Logic and the Philosophy of Mathematics

FIL2405/FIL4405 – Philosophical logic and the philosophy of mathematics Instructor Professor Øystein Linnebo Office: Georg Morgenstierne 644 Email: [email protected] Readings The readings are listed below. You must have read the readings marked by ‘*’ before class; otherwise you won’t be able to follow the discussion. You should expect to have to read the main readings several times. I have listed a number of further optional readings, which are not part of the official curriculum. Students should obtain copies of the following two books: Stewart Shapiro, Thinking about Mathematics (Oxford UP, 2000) Paul Benacerraf and Hilary Putnam, Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings 2nd ed. (Cambridge UP, 1983) The former is an excellent introduction to the subject. The latter is a classic anthology containing most of the articles we will study. All our main readings will be available in these two books, online, or through Fronter. Course overview Pure mathematics appears to be very different from the empirical sciences: It appears not to rely on experience but to be completely a priori; its truths appear to be necessary rather than contingent; and it appears to be concerned with abstract objects rather than concrete (spatiotemporal, causally efficacious) ones. These three features of pure mathematics—its apparent apriority, necessity, and concern with abstract objects—give rise to some deep and extremely interesting philosophical questions. Are these features to be taken at face value? If so, how are they to be understood? In particular, how are these features to be reconciled with a scientific world view? Alternatively, if the special features of mathematics are not taken at face value, can we give an alternative explanation of mathematics which nevertheless does justice to mathematical practice and mathematical experience? We will discuss a number of classical and contemporary approaches to these questions and related ones. -

The Metaontology of Abstraction Bob Hale and Crispin Wright

For David Chalmers et al, eds., Metametaphysics, OUP forthcoming The Metaontology of Abstraction Bob Hale and Crispin Wright §1 WeWe can can be be pretty pretty brisk brisk with withthe basics. the basics. Paul BenacerrafPaul Benacerraf famously famously wondered1 wondered how any1 how any satisfactory account account of mathematicalof mathematical knowledge knowledge could combinecould combine a face-value a face-value semantic construal semantic construal of classical mathematical theories, such as arithmetic, analysis and set-theory—one of classical mathematical theories, such as arithmetic, analysis and set-theory—one which takes which takes seriously the apparent singular terms and quantifiers in the standard seriouslyformulations the apparent—with asingular sensibly terms naturalistic and quantifiers conception in the standard of ourformulations—with knowledge-acquisitive a sensiblycapacities naturalistic as essentially conception operative of our knowledge-acquisitivewithin and subject to capacities the domain as essentially of causal operative law. The withinproblem, and verysubject simply, to the isdomain that the of causalentities law. apparently The problem, called very for simply,by the face-valueis that the entities construal — apparentlyfinite cardinals, called forreals by theand face-value sets—do construal— not, seemingly, finite cardinals, participate reals inand the sets—do causal not, swim. A refinement of the problem, due to Field, challenges us to explain what reason there is to seemingly,suppose that participate our basic in beliefs the causal about swim. such A entities, refinement encoded of the inproblem, standard due axioms, to Field, could challenges possibly usbe toformed explain reliablywhat reason by meansthere is solelyto suppose of what that ourare basic presumably beliefs about naturalistic such entities, belief-forming encoded inmechanisms.