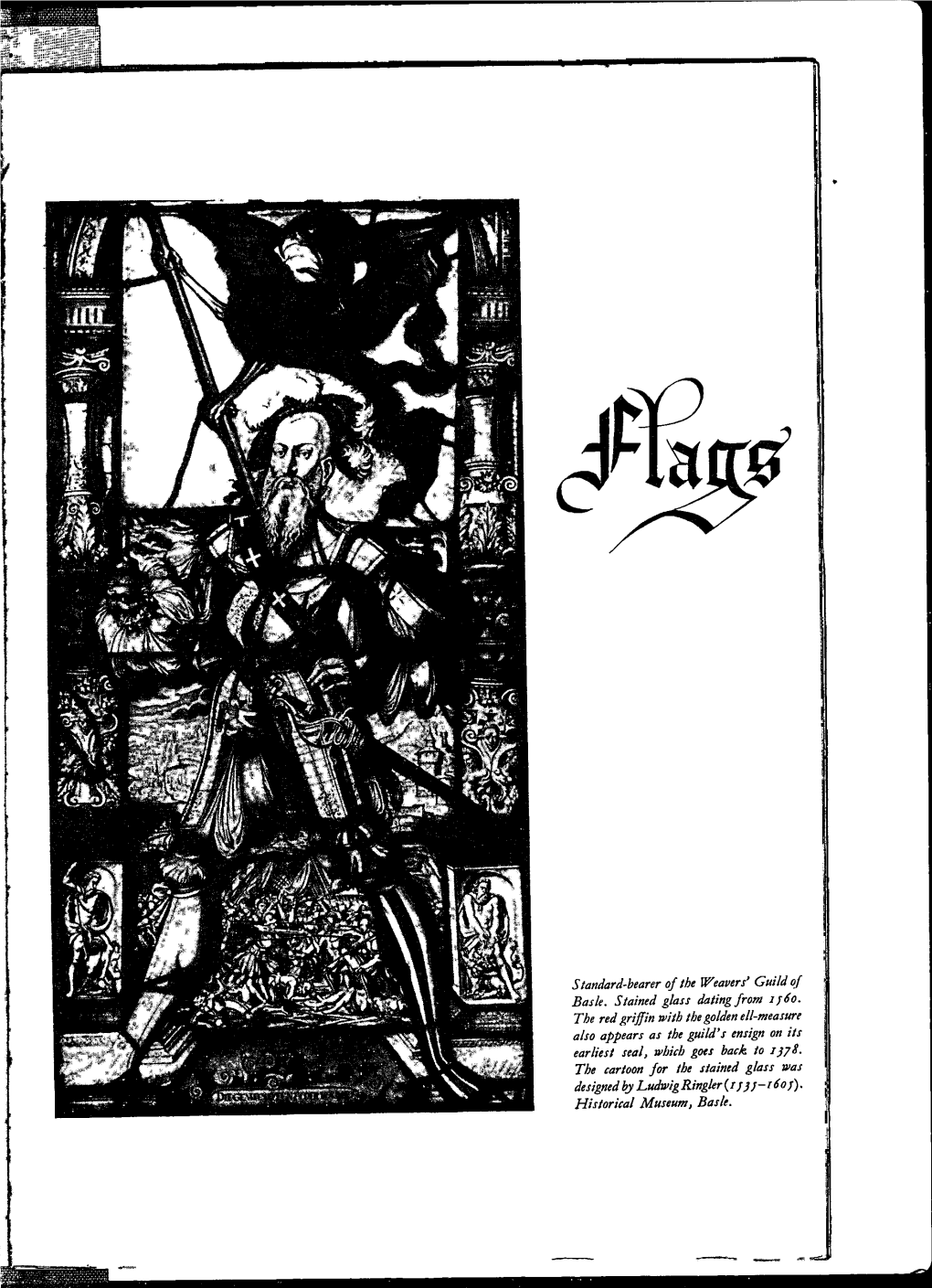

Flags/ Banners and Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boso's- Lfe of Alexdnder 111

Boso's- Lfe of Alexdnder 111 Introduction by PETER MUNZ Translated by G. M. ELLIS (AG- OXFORD . BASIL BLACKWELL @ Basil Blackwell 1973 AI1 rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval System, or uansmitted, in any form or by. any. means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permis- sion of Basil Blackwell & Mott Limited. ICBN o 631 14990 2 Library of Congress Catalog Card Num'cer: 72-96427 Printed in Great Britain by Western Printing Services Ltd, Bristol MONUMENTA GERilAANIAE I-' 11.2' I d8-:;c,-q-- Bibliothek Boso's history of Pope Alexander I11 (1159-1181) is the most re- markable Part of the Liber Pontificalis. Unlike almost all the other contributions, it is far more than an informative chronicle. It is a work of history in its own right and falsely described as a Life of Alexander 111. Boso's work is in fact a history of the Iong schism in the church brought about by the double election of I159 and perpet- uated until the Peace of Venice in I 177. It makes no claim to be a Life of Alexander because it not only says nothing about his career before his election but also purposely omits all those events and activities of his pontificate which do not strictly belong to the history of the schism. It ends with Alexander's return to Rome in 1176. Some historians have imagined that this ending was enforced by Boso's death which is supposed to have taken piace in 1178.~But there is no need for such a supposition. -

Late-Medieval France

Late-Medieval France: A Nation under Construction A study of French national identity formation and the emerging of national consciousness, before and during the Hundred Years War, 1200-1453 Job van den Broek MA History of Politics and Society Dr. Christian Wicke Utrecht University 22 June 2020 Word count: 13.738 2 “Ah! Doulce France! Amie, je te lairay briefment”1 -Attributed to Bertrand du Guesclin, 1380 Images on front page: The kings of France, England, Navarre and the duke of Burgundy (as Count of Charolais), as depicted in the Grand Armorial Équestre de la Toison d’Or, 1435- 1438. 1 Cuvelier in Charrière, volume 2, pp 320. ”Ah, sweet France, my friend, I must leave you very soon.” Translation my own. 2 3 Abstract Whether nations and nationalism are ancient or more recent phenomena is one of the core debates of nationalism studies. Since the 1980’s, modernism, claiming that nations are distinctively modern, has been the dominant view. In this thesis, I challenge this dominant view by doing an extensive case-study into late-medieval France, applying modernist definitions and approaches to a pre-modern era. France has by many regarded as one of the ‘founding fathers’ of the club of nations and has a long and rich history and thus makes a case-study for such an endeavour. I start with mapping the field of French identity formation in the thirteenth century, which mostly revolved around the royal court in Paris. With that established, I move on to the Hundred Years War and the consequences of this war for French identity. -

Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (2012)

FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard Marine and Coastal Spatial Data Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee June, 2012 Federal Geographic Data Committee FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard, June 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Need ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Application ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Relationship to Previous FGDC Standards .............................................................. 4 1.6 Development Procedures ......................................................................................... 5 1.7 Guiding Principles ................................................................................................... 7 1.7.1 Build a Scientifically Sound Ecological Classification .................................... 7 1.7.2 Meet the Needs of a Wide Range of Users ...................................................... -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Saint John Henry Newman

SAINT JOHN HENRY NEWMAN Chronology 1801 Born in London Feb 21 1808 To Ealing School 1816 First conversion 1817 To Trinity College, Oxford 1822 Fellow, Oriel College 1825 Ordained Anglican priest 1828-43 Vicar, St. Mary the Virgin 1832-33 Travelled to Rome and Mediterranean 1833-45 Leader of Oxford Movement (Tractarians) 1843-46 Lived at Littlemore 1845 Received into Catholic Church 1847 Ordained Catholic priest in Rome 1848 Founded English Oratory 1852 The Achilli Trial 1854-58 Rector, Catholic University of Ireland 1859 Opened Oratory school 1864 Published Apologia pro vita sua 1877 Elected first honorary fellow, Trinity College 1879 Created cardinal by Pope Leo XIII 1885 Published last article 1888 Preached last sermon Jan 1 1889 Said last Mass on Christmas Day 1890 Died in Birmingham Aug 11 Other Personal Facts Baptized 9 Apr 1801 Father John Newman Mother Jemima Fourdrinier Siblings Charles, Francis, Harriett, Jemima, Mary Ordination (Anglican): 29 May 1825, Oxford Received into full communion with Catholic Church: 9 October 1845 Catholic Confirmation (Name: Mary): date 1 Nov 1845 Ordination (Catholic): 1 June 1847 in Rome First Mass 5 June 1847 Last Mass 25 Dec 1889 Founder Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England Created Cardinal-Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro: 12 May 1879, in Rome, by Pope Leo XIII Motto Cor ad cor loquitur—Heart speaks to heart Epitaph Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem—Out of shadows and images into the truth Declared Venerable: 22 January 1991 by Pope St John Paul II Beatified 19 September 2010 by Pope Benedict XVI Canonized 13 October 2019 by Pope Francis Feast Day 9 October First Approved Miracle: 2001 – healing of Deacon Jack Sullivan (spinal condition) in Boston, MA Second Approved Miracle: 2013 – healing of Melissa Villalobos (pregancy complications) in Chicago, IL Newman College at Littlemore Bronze sculpture of Newman kneeling before Fr Dominic Barberi Newman’s Library at the Birmingham Oratory . -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte De Sordi with the Vicenza Mode

anticSwiss 28/09/2021 06:49:50 http://www.anticswiss.com Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi with the Vicenza mode FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 16° secolo - 1500 Ars Antiqua srl Milano Style: Altri stili +39 02 29529057 393664680856 Height:51cm Width:40.5cm Material:Olio su tela Price:3400€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: 16th century Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi with the model of the city of Vicenza Oil on oval canvas, 51 x 40.5 cm The oval canvas depicts a holy bishop, as indicated by the attributes of the miter on the head of the young man and the crosier held by angel behind him. The facial features reflect those of a beardless young man, with a full and jovial face, corresponding to a youthful depiction of the blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte (Cremona, c. 1125 - Vicenza, March 16, 1181). Another characteristic attribute is the model of the city of Vicenza that he holds in his hands, the one of which he became bishop in 1175. Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi lived at the time of the struggle undertaken by the emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1125-1190), against the Papacy and the Italian Municipalities. Giovanni was born in Cremona around 1125 from a family of noble origins; still at an early age he lost his father, his mother remarried the noble Adamo Cacciafronte, who loved him as his own son, giving him his name; he received religious and cultural training. At sixteen he entered the Abbey of San Lorenzo in Cremona as a Benedictine monk; over the years his qualities and virtues became more and more evident, and he won the sympathies of his superiors and confreres. -

2012 Economic Impacts of Marine Invasive Species

Final Report to the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council Marine Invasive Species Program Contract No. 952.11.04 FINAL REPORT: July 19, 2011 – July 31, 2012 Submitted July 31, 2012 The opinions expressed in this PWSRCAC-commissioned report are not necessarily those of PWSRCAC Project Overview Non-Indigenous Species (NIS) may specifically be classified as invasive when ecologically or economically damaging and/or causing harm to human health. We see the economic consequences of invasions in other states and regions. Alaska has not experienced significant impacts to date but examples tell us it may only be a matter of time, and all the more assured if we do nothing or little to prevent and mitigate invasions. To date, we as a state have not undertaken an economic assessment to estimate how severe an economic impact could be due to marine invasive species. Without this economic analysis the environmental arguments supporting action for an Alaska Council on Invasive Species become mute. There may be impacts, there may be environmental consequences, but a louder voice echoing the economic impacts may be required to get the ear of the Legislature. To this end we proposed to work in collaboration with the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) to assess economic benefits and costs of taking action versus no action on invasive species in Alaska. This project is a result of the Marine Invasive Species Workshop held in 2010 by the Marine Subcommittee of the Alaska Invasive Species Working Group. Workshop participants discussed the status of marine invasive species in Alaska, the state’s invasive species policies and management, and the potential impacts of marine invasive species on Alaska’s commercial, recreation, and subsistence economies. -

Manufacturing Middle Ages

Manufacturing Middle Ages Entangled History of Medievalism in Nineteenth-Century Europe Edited by Patrick J. Geary and Gábor Klaniczay LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24486-3 CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ xiii Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 PART ONE MEDIEVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY HISTORIOGRAPHY National Origin Narratives in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy ..... 13 Walter Pohl The Uses and Abuses of the Barbarian Invasions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries ......................................................................... 51 Ian N. Wood Oehlenschlaeger and Ibsen: National Revival in Drama and History in Denmark and Norway c. 1800–1860 ................................. 71 Sverre Bagge Romantic Historiography as a Sociology of Liberty: Joachim Lelewel and His Contemporaries ......................................... 89 Maciej Janowski PART TWO MEDIEVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARCHITECTURE The Roots of Medievalism in North-West Europe: National Romanticism, Architecture, Literature .............................. 111 David M. Wilson Medieval and Neo-Medieval Buildings in Scandinavia ....................... 139 Anders Andrén © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24486-3 vi contents Restoration as an Expression -

Bro Nevez 84

1 BRO NEVEZ 95 August 2005 ISSN 0895 3074 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Editor: Lois Kuter (215) 886-6361 169 Greenwood Ave., B-4 [email protected] (NEW !!!) Jenkintown, PA 19046 U.S.A. ___________________________________________________________________________________________ The U.S. Branch of the International Committee for the Defense of the Breton Language (U.S. ICDBL) was incorporated as a not-for-profit corporation on October 20, 1981. Bro Nevez ("new country" in the Breton language) is the newsletter produced by the U.S. ICDBL It is published quarterly: February, May, August and November. Contributions, letters to the Editor, and ideas are welcome from all readers and will be printed at the discretion of the Editor. The U.S. ICDBL provides Bro Nevez on a complimentary basis to a number of language and cultural organizations in Brittany to show our support for their work. Your Membership/Subscription allows us to do this. Membership (which includes subscription) for one year is $20. Checks should be in U.S. dollars, made payable to “U.S. ICDBL” and mailed to Lois Kuter at the address above. Dues and contributions can also be sent electronically via the U.S. ICDBL web site – see below Ideas expressed within this newsletter are those of the individual authors, and do not necessarily represent ICDBL philosophy or policy. For information about the Canadian ICDBL contact: Jeffrey D. O’Neill, 1111 Broadview Ave. #205, Toronto, Ontario, M4K 2S4, CANADA (e-mail: [email protected]). Telephone: (416) 913-1499. U.S. ICDBL website: www.breizh.net/icdbl.htm From the Editor: The Breton Language in Crisis – Where do we go from here? Lois Kuter A recent article on the Eurolang website support for the Breton language from the (www.eurolang.net) reported on a seminar French government and European level held at the Summer University at the institutions. -

2016 Results

2016 Results Protecting citizens and consumers, supporting businesses FOREWORD 2016 was another milestone year for French Customs. For the first time in nearly a century, French Customs officers marched in the traditional 14 July parade on Paris’s Champs-Elysées. This was an expression of the nation’s gratitude to French Customs and its staff, who are fully involved in the fight against terrorism, working alongside the other government departments that help keep France secure. This recognition also took the form of a plan to bolster French Customs’ resources to allow it to more effectively combat terrorism. Half of the 1,000 additional hires announced by President Hollande for 2016 and 2017 have already been assigned to operational surveillance units, and the rest will join them in 2017 as soon as their training is completed. Operational units will also receive additional weapons, bullet-resistant apparel and detection equipment. IT systems to combat fraud and to assist communication between surveillance teams are also being deployed. In 2016, we achieved remarkable results in terms of combating every form of trafficking and illegal financial flows. After the record seizures of narcotics and smuggled tobacco in 2015, the past year’s results remained at very high levels. In several areas, we broke records: nearly €150 million in criminal assets were seized or identified (a 170% increase over 2015), and more than 9 million counterfeit items were intercepted. These excellent results are a reminder that French Customs’ protection efforts extend to the full range of threats to France. The new Union Customs Code entered into effect in 2016. -

20' Up! Making and Flying Silk War Standards

20’ Feet Up! Making and Flying Silk War Standards. Baroness Theodora Delamore and Baron Alan Gravesend, UofA#73, Oct 2008. 20’ Up! Making and Flying silk war standards Baroness Theodora Delamore, OP and Baron Alan Gravesend, OP October 6, 2008. University of Atlantia, Session#73 Course outline • The language of vexillology in general, and the anatomy of standards in particular • Historical examples of war standards (or not many cloth things survive). • Designing your own war standards (while there are no cut and dry rules, there’s a general trend) • Basic silk painting skills necessary for producing your own war standard • A flag pole all your own (or 20’ up!) Vexillology: The study of flags Finial Banner: A flag that generally corresponds exactly to a coat of arms. Finial: (often decorative) top of the flag staff. Fly: Part of a flag opposite the staff (sinister) Hoist Fly Gonfalon: Flag hung from a crossbar Ground: the field of the flag. Width Hoist: part of the flag nearest the staff (dexter) Livery colors: principal tinctures of a coat of Length Staff arms; typically a color and metal Pencel, Pennon: small flag, such as a lance Anatomy of a Flag (W. Morgenstern) flag; armirgeous. Often bears a badge against livery colors. (Modern version = pennant.) Pennoncelle: long, narrow pennon or streamer. Often single pointed. Pinsil: Scotish pennon, featuring the owner’s crest & motto in the hoist and badge in the fly Schwenkel: a single long tail extended from the upper fly corner of a flag. Standard: long, tapering flag of heraldic design. Swallow tailed – having a large triangular section cut out of the fly end.