Elizabethan England: Revision Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigative Leads for Use in the Ensuing Cold War

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 24, June 22, 1982 were made to preserve strains of the Nazi experiment Investigative Leads for use in the ensuing Cold War. Major branches of the Order There are four primary branches of the original crusading Hospitaler Order in existence today: The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM) was rechartered by the Papacy in 1815. When Napoleon conquered the Hospitaler's island base of Malta in 1798, Hospitaler knights Czar Paul I of Russia assumed protectorship of the Order. After his assassination, his son, Alexander I, of a new dark age relinquished this office to the Papacy. The SMOM remains affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, though it has been condemned by Popes John XXIII by Scott Thompson and Paul VI. It is the only branch with true sovereignty, and has diplomatic immunity for its emissaries and Investigation into the networks responsible for the May offices on the Via Condotti in Rome. Under the current 12, 1982 attempt to assassinate Pope John Paul II has Grand Master, Prince Angelo de Mojana di Colonna, now uncovered the fact that Secretary of State Alexander the SMOM is controlled by the leading families of the Haig is a witting participant in a secret-cult network that Italian "black nobility," including the House of Savoy, poses the principal assassination-threat potential against Pallavicinis, Orsinis, Borgheses, and Spadaforas. both President Ronald Reagan and the Pope. The SMOM represents the higher-level control over This network centers upon the transnational branch the Propaganda-2 Masonic Lodge of former Mussolini es of the Hospitaler Order (a.k.a. -

Early Elizabethan England, 1558-88 Home Learning Booklet KT2

Thamesview School History Early Elizabethan England, 1558-88 Home Learning Booklet KT2: Challenges at Home and Abroad, 1569-88 Instructions • Complete the knowledge recall sections of the booklet. • Answer the exam questions. Plots and Revolts at Home 1. Write the number of each of the following events and developments in the appropriate column to identify whether it was a key cause, event or consequence of the Revolt of the Northern Earls. Cause Event Consequence 1: The Earl of Sussex assembled a 2: The earls had political and 3: From 9 to 15 November 1569 huge royal army of 10,000 men, economic grievances against the earls of Northumberland and causing the Northern Earls to turn Elizabeth. She had weakened Westmorland urged all their back their march and escape into their control by appointing a tenants to join their army and Scotland. The Earl of Council of the North and had march south to bring an end to Northumberland was later taken lands from nobles, the Privy Council, which executed, along with 450 rebels. including the Earl of supported Elizabeth’s policies. Northumberland. 4: The revolt had little chance of 5: Elizabeth’s government did not 6: The earls had strong Catholic success since it was ineffectively panic. Officials in the north traditions, and both had taken led, confused in its aims and prevented rebels from taking key part in a plan to marry Mary lacked the support of most towns and were successful in Queen of Scots to the Duke of English Catholics, who were not raising a huge army in support of Norfolk to further support her committed to the revolt. -

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth 1 Notes for a CE Source Question Introduction

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth 1 Notes for a CE Source Question Introduction Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587) Mary was the daughter of James V of Scotland and Mary of Guise. She became Queen of Scotland when she was six days old after her father died at the Battle of Solway Moss. A marriage was arranged between Mary and Edward, only son of Henry VIII but was broken when the Scots decided they preferred an alliance with France. Mary spent a happy childhood in France and in 1558 married Francis, heir to the French throne. They became king and queen of France in 1559. Francis died in 1560 of an ear infection and Mary returned to Scotland a widow in 1561. During Mary's absence, Scotland had become a Protestant country. The Protestants did not want Mary, a Catholic and their official queen, to have any influence. In 1565 Mary married her cousin and heir to the English throne, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. The marriage was not a happy one. Darnley was jealous of Mary's close friendship with her secretary, David Rizzio and in March 1566 had him murdered in front of Mary who was six months pregnant with the future James VI and I. Darnley made many enemies among the Scottish nobles and in 1567 his house was blown up. Darnley's body was found outside in the garden, he had been strangled. Three months later Mary married the chief suspect in Darnley’s murder, the Earl of Bothwell. The people of Scotland were outraged and turned against her. -

Form Foreign Policy Took- Somerset and His Aims: Powers Change? Sought to Continue War with Scotland, in Hope of a Marriage Between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots

Themes: How did relations with foreign Form foreign policy took- Somerset and his aims: powers change? Sought to continue war with Scotland, in hope of a marriage between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Charles V up to 1551: The campaign against the Scots had been conducted by Somerset from 1544. Charles V unchallenged position in The ‘auld alliance’ between Franc and Scotland remained, and English fears would continue to be west since death of Francis I in dominated by the prospect of facing war on two fronts. 1547. Somerset defeated Scots at Battle of Pinkie in September 1547. Too expensive to garrison 25 border Charles won victory against forts (£200,000 a year) and failed to prevent French from relieving Edinburgh with 10,000 troops. Protestant princes of Germany at In July 1548, the French took Mary to France and married her to French heir. Battle of Muhlberg, 1547. 1549- England threatened with a French invasion. France declares war on England. August- French Ottomans turned attention to attacked Boulogne. attacking Persia. 1549- ratified the Anglo-Imperial alliance with Charles V, which was a show of friendship. Charles V from 1551-1555: October 1549- Somerset fell from power. In the west, Henry II captured Imperial towns of Metz, Toul and Verdun and attacked Charles in the Form foreign policy-Northumberland and his aims: Netherlands. 1550- negotiated a settlement with French. Treaty of In Central Europe, German princes Somerset and Boulogne. Ended war, Boulogne returned in exchange for had allied with Henry II and drove Northumberland 400,000 crowns. England pulled troops out of Scotland. -

Nobility in Middle English Romance

Nobility in Middle English Romance Marianne A. Fisher A dissertation submitted for the degree of PhD Cardiff University 2013 Summary of Thesis: Postgraduate Research Degrees Student ID Number: 0542351 Title: Miss Surname: Fisher First Names: Marianne Alice School: ENCAP Title of Degree: PhD (English Literature) Full Title of Thesis Nobility in Middle English Romance Student ID Number: 0542351 Summary of Thesis Medieval nobility was a compound and fluid concept, the complexity of which is clearly reflected in the Middle English romances. This dissertation examines fourteen short verse romances, grouped by story-type into three categories. They are: type 1: romances of lost heirs (Degaré, Chevelere Assigne, Sir Perceval of Galles, Lybeaus Desconus, and Octavian); type 2: romances about winning a bride (Floris and Blancheflour, The Erle of Tolous, Sir Eglamour of Artois, Sir Degrevant, and the Amis– Belisaunt plot from Amis and Amiloun); type 3: romances of impoverished knights (Amiloun’s story from Amis and Amiloun, Sir Isumbras, Sir Amadace, Sir Cleges, and Sir Launfal). The analysis is based on contextualized close reading, drawing on the theories of Pierre Bourdieu. The results show that Middle English romance has no standard criteria for defining nobility, but draws on the full range on contemporary opinion; understandings of nobility conflict both between and within texts. Ideological consistency is seldom a priority, and the genre apparently serves neither a single socio-political agenda, nor a single socio-political group. The dominant conception of nobility in each romance is determined by the story-type. Romance type 1 presents nobility as inherent in the blood, type 2 emphasizes prowess and force of will, and type 3 concentrates on virtue. -

Oxford DNB: May 2021

Oxford DNB: May 2021 Welcome to the seventy-fourth update of the Oxford DNB, which adds 18 new lives and 1 portrait likeness. The newly-added biographies range from the noblewoman Jane Dudley, duchess of Northumberland, to Eleanor Cavanagh, lady’s maid and correspondent from Russia, and include a cluster with a focus on catholic lay culture in early modern England. They have been curated and edited by Dr Anders Ingram of the ODNB. From May 2021, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford DNB) offers biographies of 64, 115men and women who have shaped the British past, contained in 61, 787 articles. 11,802 biographies include a portrait image of the subject – researched in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery, London. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to the Oxford DNB, which means you can access the complete dictionary for free via your local library. Libraries offer 'remote access' that enables you to log in at any time at home (or anywhere you have internet access). Elsewhere, the Oxford DNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Full details of participating British public libraries, and how to gain access to the complete dictionary, are available here. May 2021: summary of newly-added content The lives in this month’s update focus on Early Modern Women and particularly on the adaptions of underground catholic lay culture in the face of religious turbulence and persecution in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England. Joan Aldred [née Ferneley] (b. 1546, d. after 12 Oct 1625), and her husband Solomon were catholic activists who seem to have received a papal pension for their role in supporting the landing of the secret Jesuit mission of Edmund Campion. -

Shakespeare, Middleton, Marlowe

UNTIMELY DEATHS IN RENAISSANCE DRAMA UNTIMELY DEATHS IN RENAISSANCE DRAMA: SHAKESPEARE, MIDDLETON, MARLOWE By ANDREW GRIFFIN, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University ©Copyright by Andrew Griffin, July 2008 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2008) McMaster University (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Untimely Deaths in Renaissance Drama: Shakespeare, Middleton, Marlowe AUTHOR: Andrew Griffin, M.A. (McMaster University), B.A. (Queen's University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Helen Ostovich NUMBER OF PAGES: vi+ 242 ii Abstract In this dissertation, I read several early modem plays - Shakespeare's Richard II, Middleton's A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, and Marlowe's Dido, Queene ofCarthage alongside a variety of early modem historiographical works. I pair drama and historiography in order to negotiate the question of early modem untimely deaths. Rather than determining once and for all what it meant to die an untimely death in early modem England, I argue here that one answer to this question requires an understanding of the imagined relationship between individuals and the broader unfolding of history by which they were imagined to be shaped, which they were imagined to shape, or from which they imagined to be alienated. I assume here that drama-particularly historically-minded drama - is an ideal object to consider when approaching such vexed questions, and I also assume that the problematic of untimely deaths provides a framework in which to ask about the historico-culturally specific relationships that were imagined to obtain between subjects and history. While it is critically commonplace to assert that early modem drama often stages the so-called "modem" subject, I argue here that early modem visions of the subject are often closely linked to visions of that subject's place in the world, particularly in the world that is recorded by historiographers as a world within and of history. -

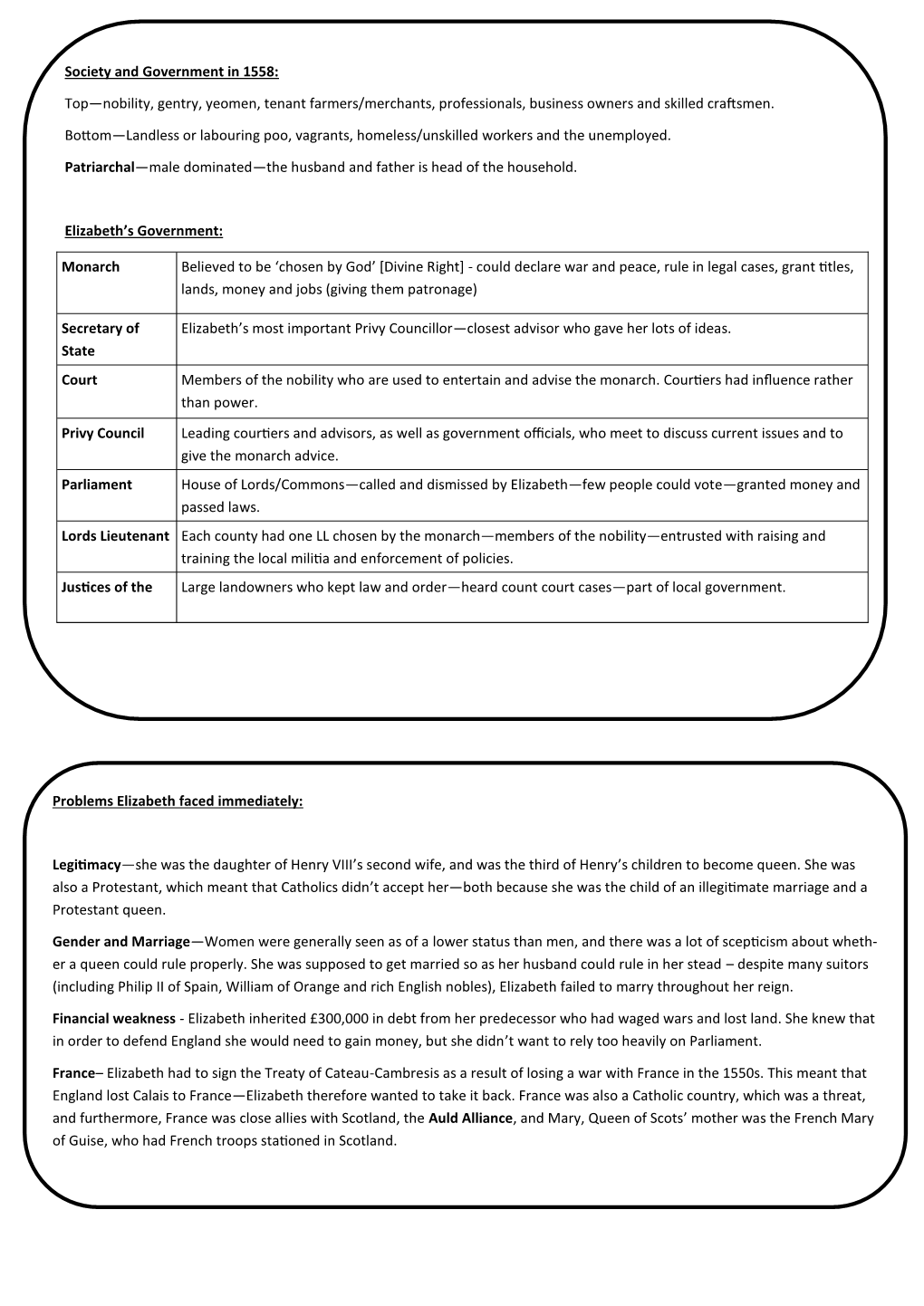

Early Elizabethan England, 1558-88 REVISION SHEET Key Topic 1

Early Elizabethan England, 1558-88 REVISION SHEET Key topic 1: Queen, government and religion, 1558-69 Society Government Hierarchy in countryside Hierarchy in towns Court – Noblemen who advised 1. Nobility 1. Merchants the queen 2. Gentry 2. Professionals Parliament – Houses of Lords 3. Yeomen 3. Business owners and Commons. Advised 4. Tenant farmers 4. Skilled craftsmen Elizabeth’s government 5. Landless and working poor 5. Unskilled workers Privy Council – Nobles who 6. Homeless and beggars 6. Unemployed helped govern the country Elizabeth’s problems when she became queen in 1558: She was young and inexperienced. She was Protestant so not supported by English Catholics. Many people (especially Catholics) thought she was illegitimate and had no right to the throne. She was unmarried. Financial weaknesses – The Crown (government) was £300,000 in debt. Mary I had sold off Crown lands (making it hard for Elizabeth to raise money) and borrowed from foreign countries (who charged high interest rates). Challenges from abroad – France, Spain and Scotland were all Catholic countries and believed Mary, Queen of Scots had a stronger claim to the throne of England than Elizabeth. France and Scotland were old allies. Elizabeth’s character – She was very well educated, confident and charismatic. She believed in her divine right to rule. She had an excellent understanding of politics. She was strong willed and stubborn. Religious Divisions in 1558 Catholic Protestant Puritan Pope is head of the church No pope Very strict Protestants Priests can forgive sins Only God can forgive sins (shared many beliefs but Bread and wine become the body and Bread and wine represent the body and more extreme, e.g. -

William Herle and the English Secret Service

William Herle and the English Secret Service Michael Patrick Gill A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Victoria University of Wellington 2010 ii Table of Contents Abstract iii Abbreviations iv Transcription Policy and Note on Dates v Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter I: Herle‘s Early Life 12 Chapter II: The Ridolfi Plot 40 Chapter III: Contrasts in Patronage 65 Chapter IV: Herle in the Netherlands 97 Chapter V: the End of Herle‘s Career 112 Conclusion 139 Bibliography 145 iii Abstract This thesis examines William Herle‘s life through his surviving letters to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and other Elizabethan Privy Councillors. It emphasises the centrality of the Elizabethan patronage system to Herle‘s life, describing how his ties to Cecil helped Herle escape prison, avoid his creditors, and gain recompense for his service to Elizabeth. In exchange for Cecil‘s protection, Herle became deeply involved in Elizabethan intelligence networks, both domestic and foreign, throughout the 1570s and 1580s. Herle helped uncover plots against Elizabeth, passed vital information about events in the Spanish Netherlands back to England, and provided analyses of English foreign policy for his superiors. Despite his vital role, Herle never experienced true success, and died deeply in debt and abandoned by his patrons. Herle‘s life allows us wider insights into Elizabethan government and society. His experiences emphasises the inefficient nature of the Tudor foreign service, which utilised untrained diplomats who gained their position through political connections and were left to pay their own way through taking out loans they had little hope of repaying. -

Throckmorton of Coughton and Wigmore of Lucton

John THROCKMORTON Eleanor SPINETO Died: 1445 Treasurer of England Thomas THROCKMORTON Margaret OLNEY John THROCKMORTON Isabel BRUGES Died: 1436 Elizabeth BAYNHAM Robert THROCKMORTON Catherine MARROW John THROCKMORTON Richard THROCKMORTON Edward PEYTO Goditha THROCKMORTON Richard MIDDLEMORE of Mary THROCKMORTON William TRACY Margaret THROCKMORTON Thomas MIDDLEMORE Eleanor THROCKMORTON John THROCKMORTON ancestor of Throckmortons of Claxton ancestor of Throckmortons of Great Edgbaston and Southeltham Stoughton Died: 1499 Thomas GIFFARD of Chillington Ursula THROCKMORTON George THROCKMORTON Katherine VAUX Richard THROCKMORTON Joan BEAUFO Thomas BURDET of Brancot Mary THROCKMORTON Richard MIDDLEMORE of Sir Thomas ENGLEFIELD Elizabeth THROCKMORTON Anthony THROCKMORTON Margaret THROCKMORTON Christopher THROCKMORTON Sheriff of Warks and Leics Died: 1547 Edgbaston Died: 1537 Sheriff of Glocs Muriel BERKELEY Robert THROCKMORTON Elizabeth HUSSEY Clement THROCKMORTON Catherine NEVILLE Nicholas THROCKMORTON Anne CAREW John THROCKMORTON Margaret PUTTENHAM George THROCKMORTON Sir John HUBALD of Ipsley Mary THROCKMORTON John GIFFORD of Ichell Elizabeth THROCKMORTON Gabriel THROCKMORTON Emma LAWRENCE William THROCKMORTON Died: 1570 (app) ancestor of Throckmortons of Haseley Born: 1515 Died: 1580 probable parentage Died: 1553 Died: 1571 Judge in Chester. Ambassador Thomas THROCKMORTON Margaret WHORWOOD Sir John GOODWIN of Elizabeth THROCKMORTON Henry NORWOOD Catherine THROCKMORTON Ralph SHELDON Anne THROCKMORTON Edward ARDEN of Park Hall Mary THROCKMORTON -

The Catholic Plots Early Life 1560 1570 1580 1590 1600

Elizabethan England: Part 1 – Elizabeth’s Court and Parliament Family History Who had power in Elizabethan England? Elizabeth’s Court Marriage The Virgin Queen Why did Parliament pressure Elizabeth to marry? Reasons Elizabeth chose Group Responsibilities No. of people: not to marry: Parliament Groups of people in the Royal What did Elizabeth do in response by 1566? Who was Elizabeth’s father and Court: mother? What happened to Peter Wentworth? Council Privy What happened to Elizabeth’s William Cecil mother? Key details: Elizabeth’s Suitors Lieutenants Robert Dudley Francis Duke of Anjou King Philip II of Spain Who was Elizabeth’s brother? Lord (Earl of Leicester) Name: Key details: Key details: Key details: Religion: Francis Walsingham: Key details: Who was Elizabeth’s sister? Justices of Name: Peace Nickname: Religion: Early Life 1560 1570 1580 1590 1600 Childhood 1569 1571 1583 1601 Preparation for life in the Royal The Northern Rebellion The Ridolfi Plot The Throckmorton Plot Essex’s Rebellion Court: Key conspirators: Key conspirators: Key conspirators: Key people: Date of coronation: The plan: The plan: The plan: What happened? Age: Key issues faced by Elizabeth: Key events: Key events: Key events: What did Elizabeth show in her response to Essex? The Catholic Plots Elizabethan England: Part 2 – Life in Elizabethan Times Elizabethan Society God The Elizabethan Theatre The Age of Discovery Key people and groups: New Companies: New Technology: What was the ‘Great Chain of Being’? Key details: Explorers and Privateers Francis Drake John Hawkins Walter Raleigh Peasants Position Income Details Nobility Reasons for opposition to the theatre: Gentry 1577‐1580 1585 1596 1599 Drake Raleigh colonises ‘Virginia’ in Raleigh attacks The Globe Circumnavigation North America. -

A.P. European History. Western Heritage Chapter 12 the Age of Religious Wars September 2017

A.P. European History. Western Heritage Chapter 12 The Age of Religious Wars September 2017 All assignments and dates are subject to change. Assignments Due 1. Read pp. 390-395 The French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) September 3, Sunday 2. Read pp. 395-404 Imperial Spain and the Reign of Philip II (1556-1598) September 6, Wednesday England & Spain (1553-1603) 3. Read pp. 404-413 The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) September 8, Friday 4. SAQ QUIZ TBA 5. All Bp”s & 1 outline are due September 15 Friday 6. http://www.historyguide.org/earlymod/lecture6c.html Read!! 7. Chapter 12 Test September 15 Friday Study Guide for Chapter 12 - The Age of Religious Wars Terms and People to Know Sec 1. (pgs 388-395) presbyters Counter-Reformation baroque Peter Paul Reubens Gianlorenzo Bernini Christopher Wren Rembrandt van Rijn politiques Huguenots Edict of Fontainebleau Edict of Chateaubriand Henry of Navarre Catherine de Medici Bourbons Guises Louis I, Prince of Condy Admiral Gaspard de Coligny Conspiracy of Amboise Theodore Beza Francis II Charles IX January Edict Peace of St. Germain-en-Laye Battle of Lepanto Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre Henry of Navarre Franco - Gallia Francois Hotman On the Right of Magistrates over Their Subjects Henry III The Peace of Beaulieu The Day of Barricades Henry IV The Edict of Nantes Treaty of Vervins Sec 2. (pgs 395-401) Spanish Armada Philip II Ferdinand I Potosi ( Bolivia ) Zacatecas (Mexico) inflation The Escorial Don Carlos Don John of Austria The Battle of Lepanto annexation of Portugal Cardinal Granvelle Margaret of Parma The Count of Egmont William of Nassau ( of Orange) Anne of Saxony Louis of Nassau The Compromise The Duke of Alba The Council of Trouble "tenth penny tax" Stadholder "Sea Beggars" Don Luis de Requesens "The Spanish Fury" The Pacification of Ghent Union of Brussels The Perpetual Edict of 1577 The Union of Arras The Union of Utrecht " The Apology" Duke of Alencon Maurice of Orange Treaty of Joinville Twelve Year's Truce Sec 3.