The Making of Disgrace Kelly: Dragging the Diva Through Cabarets, Pubs and Into the Recital Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera Trying to find a balance between what the verbal descriptions of Toscanini’s conducting during the period of roughly 1895-1915 say of him and what he actually did can be like trying to capture lightning in a bottle. Since he made no recordings before December 1920, and instrumental recordings at that, we cannot say with any real certainty what his conducting style was like during those years. We do know, from the complaints of Tito Ricordi, some of which reached Giuseppe Verdi’s ears, that Italian audiences hated much of what Toscanini was doing: conducting operas at the written tempos, not allowing most unwritten high notes (but not all, at least not then), refusing to encore well-loved arias and ensembles, and insisting in silence as long as the music was being played and sung. In short, he instituted the kind of audience decorum we come to expect today, although of course even now (particularly in Italy and America, not so much in England) we still have audiences interrupting the flow of an opera to inject their bravos and bravas when they should just let well enough alone. Ricordi complained to Verdi that Toscanini was ruining his operas, which led Verdi to ask Arrigo Boïto, whom he trusted, for an assessment. Boïto, as a friend and champion of the conductor, told Verdi that he was simply conducting the operas pretty much as he wrote them and not allowing excess high notes, repeats or breaks in the action. Verdi was pleased to hear this; it is well known that he detested slowly-paced performances of his operas and, worse yet, the interpolated high notes he did not write. -

The Gem Project Mini Writers and Media Summit Benefit

The Gem Project Mini Writers and Media Summit Benefit Overview: On March 1, 2012, The Gem Project will host their mini writers and media summit, as part of their networking benefit series. The series expects to garner young professionals who wish to network with those who are interested in but not limited to starting careers in writing and media. Panelists are contributors of magazines, award-winning bloggers, editors, free-lance writers, and social media strategists. Date : Thursday, March 1, 2012. Time: 7:30 PM - 10:30 PM Host: The Gem Project, Inc. Venue: The Coffee Cave, 45 Halsey Street, Newark, NJ 07102 Price: $15, $10 with promo codes. Ticket Page: http://writeforyou.eventbrite.com or http://thegemproject.org/network Twitter Hashtag: #gemproj Contact: 973-506-9275 e-mail: [email protected] Complimentary Gift bags, Favors, Speed Networking, Open Networking, & Panel Discussion + Q&A Latest addition to the growing line-up include: Corynne L. Corbett, Beauty Editor of ESSENCE magazine Corynne L. Corbett is beauty director for ESSENCE, the nation’s premier lifestyle publication for African-American women. In this new role, Corbett is responsible for leading the beauty team and executing the overall beauty vision for the magazine—in addition to writing, assigning and editing articles. Corbett is a veteran journalist who uses her 20 years of experience in fashion, beauty and lifestyle to create engaging and compelling content across a variety of media platforms. Before joining ESSENCE, she served as executive editor of Real Simple magazine, where she oversaw the coverage of fashion, beauty and food for the magazine. -

Enrico Caruso

NI 7924/25 Also Available on Prima Voce ENRICO CARUSO Opera Volume 3 NI 7803 Caruso in Opera Volume One NI 7866 Caruso in Opera Volume Two NI 7834 Caruso in Ensemble NI 7900 Caruso – The Early Years : Recordings from 1902-1909 NI 7809 Caruso in Song Volume One NI 7884 Caruso in Song Volume Two NI 7926/7 Caruso in Song Volume Three 12 NI 7924/25 NI 7924/25 Enrico Caruso 1873 - 1921 • Opera Volume 3 and pitch alters (typically it rises) by as much as a semitone during the performance if played at a single speed. The total effect of adjusting for all these variables is revealing: it questions the accepted wisdom that Caruso’s voice at the time of his DISC ONE early recordings was very much lighter than subsequently. Certainly the older and 1 CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA, Mascagni - O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa 2.50 more artistically assured he became, the tone became even more massive, and Rec: 28 December 1910 Matrix: B-9745-1 Victor Cat: 87072 likewise the high A naturals and high B flats also became even more monumental in Francis J. Lapitino, harp their intensity. But it now appears, from this evidence, that the baritone timbre was 2 LA GIOCONDA, Ponchielli - Cielo e mar 2.57 always present. That it has been missed is simply the result of playing the early discs Rec: 14 March 1910 Matrix: C-8718-1 Victor Cat: 88246 at speeds that are consistently too fast. 3 CARMEN, Bizet - La fleur que tu m’avais jetée (sung in Italian) 3.53 Rec: 7 November 1909 Matrix: C-8349-1 Victor Cat: 88209 Of Caruso’s own opinion on singing and the effort required we know from a 4 STABAT MATER, Rossini - Cujus animam 4.47 published interview that he believed it should be every singers aim to ensure ‘that in Rec: 15 December 1913 Matrix: C-14200-1 Victor Cat: 88460 spite of the creation of a tone that possesses dramatic tension, any effort should be directed in 5 PETITE MESSE SOLENNELLE, Rossini - Crucifixus 3.18 making the actual sound seem effortless’. -

ARSC Journal

HISTORIC VOCAL RECORDINGS STARS OF THE VIENNA OPERA (1946-1953): MOZART: Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail--Wer ein Liebchen hat gafunden. Ludwig Weber, basso (Felix Prohaska, conductor) ••.• Konstanze ••• 0 wie angstlich; Wenn der Freude. Walther Ludwig, tenor (Wilhelm Loibner) •••• 0, wie will ich triumphieren. Weber (Prohaska). Nozze di Figaro--Non piu andrai. Erich Kunz, baritone (Herbert von Karajan) •••• Voi che sapete. Irmgard Seefried, soprano (Karajan) •••• Dove sono. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano (Karajan) . ..• Sull'aria. Schwarzkopf, Seefried (Karajan). .• Deh vieni, non tardar. Seefried (Karajan). Don Giovanni--Madamina, il catalogo e questo. Kunz (Otto Ackermann) •••• Laci darem la mano. Seefried, Kunz (Karajan) • ••• Dalla sua pace. Richard Tauber, tenor (Walter Goehr) •••• Batti, batti, o bel Masetto. Seefried (Karajan) •.•• Il mio tesoro. Tauber (Goehr) •••• Non mi dir. Maria Cebotari, soprano (Karajan). Zauberfl.Ote- Der Vogelfanger bin ich ja. Kunz (Karajan) •••• Dies Bildnis ist be zaubernd schon. Anton Dermota, tenor (Karajan) •••• 0 zittre nicht; Der Holle Rache. Wilma Lipp, soprano (Wilhelm Furtwangler). Ein Miidchen oder Weibchen. Kunz (Rudolf Moralt). BEETHOVEN: Fidelio--Ach war' ich schon. Sena Jurinac, soprano (Furtwangler) •••• Mir ist so wunderbar. Martha Modl, soprano; Jurinac; Rudolf Schock, tenor; Gottlob Frick, basso (Furtwangler) •••• Hat man nicht. Weber (Prohaska). WEBER: Freischutz--Hier im ird'schen Jammertal; Schweig! Schweig! Weber (Prohaska). NICOLAI: Die lustigen Weiher von Windsor--Nun eilt herbei. Cebotari {Prohaska). WAGNER: Meistersinger--Und doch, 'swill halt nicht gehn; Doch eines Abends spat. Hans Hotter, baritone (Meinhard von Zallinger). Die Walkilre--Leb' wohl. Hotter (Zallinger). Gotterdammerung --Hier sitz' ich. Weber (Moralt). SMETANA: Die verkaufte Braut--Wie fremd und tot. Hilde Konetzni, soprano (Karajan). J. STRAUSS: Zigeuner baron--0 habet acht. -

Signerede Plader Og Etiketter Og Fotos Signed Records and Labels and Photos

Signerede plader og etiketter og fotos Signed records and labels and photos Soprano Blanche Arral (10/10-1864 – 3/3-1945) Born in Belgium as Clara Lardinois. Studied under Mathilde Marchesi in Paris. Debut in USA at Carnegie Hall in 1909. Joined the Met 1909-10. Soprano Frances Alda (31/5-1879 – 18/9-1953) Born Fanny Jane Davis in New Zealand. Studied with Mathilde Marchesi in Paris, where she had her debut in 1904. Married Guilio Gatti-Casazza – the director of The Met – in 1910. Soprano Geraldine Farrar – born February 28, 1882 – in Melrose, Massachusetts – died March 11, 1967 in Ridgefield, Connecticut Was also the star in more than 20 silent movies. Amercian mezzo-soprano Zélie de Lussan – 1861 – 1949 (the signature is bleached) American tenor Frederick Jagel – June, 10, 1897 Brooklyn NY – July 5, 1982, San Francisco, California At the Met from 1927 - 1950 Soprano Elisabeth Schwartzkopf – Met radio transmission on EJS 176 One of the greatest coloratura sopranos. Tenor Benjamino Gigli (20/3-1890 – 30/11-1957) One of the greatest of them all. First there was Caruso, then Gigli, then Björling and last Pavarotti. Another great tenor - Guiseppe di Stefano (24/7-1921 – 3/3-2008) The Italian tenor Guiseppe Di Stefano’s carreer lasted from the late 40’s to the early 70’s. Performed and recorded many times with Maria Callas. French Tenor Francisco (Augustin) Nuibo (1/5-1874 Marseille – Nice 4.1948) The Paris Opéra from 1900. One season at The Met in 1904/05. Tenor Leo Slezak (18/8-1873 – 1/6-1946) born in what became Czeckoslovakia. -

Himedia Signe Avec Universal Networks International

Communiqué de presse UNIVERSAL NETWORKS INTERNATIONAL ANNONCE LA PRISE EN RÉGIE DES SITES INTERNET DES CHAINES 13ème RUE, SYFY ET E! PAR HIMEDIA Paris – Mercredi 5 février, 8h00 – Universal Networks International (UNI), la division des chaînes de télévision du groupe NBCUniversal, a signé avec HiMedia, leader européen des régies publicitaires on-line, un contrat de régie exclusive pour les chaînes 13ème RUE, Syfy et E! Par cette signature, HiMedia s’engage à gérer les espaces publicitaires des sites internet des chaînes Syfy, la chaîne du fantastique (www.syfy.fr), 13ème RUE, la chaîne crime et suspense (www.13emerue.fr), ainsi que la chaîne de la culture Pop, E! (http://fr.eonline.com/). Ces chaînes sont reçues par près de 15 millions de personnes en France. L’objectif de cette nouvelle collaboration est de maximiser et d’optimiser les revenus des espaces publicitaires digitaux des chaînes. Les sites Internet vont être accompagnés dans leur développement grâce aux expertises digitales de HiMedia : Fullscreen – la régie publicitaire vidéo, Mobvious – la régie mobile, Magic – la cellule opérations spéciales et brand content et Adexchange.com – la place de marché publicitaire en temps réel. À propos d’Universal Networks International Universal Networks International est une filiale de NBCUniversal, un des acteurs majeurs dans le secteur des medias et du divertissement. Le groupe propose ainsi des contenus de qualité dans près de 176 pays à travers l’Europe, le Moyen-Orient, l’Amérique latine et l’Asie-Pacifique. NBCUniversal possède et exploite à l’international un portefeuille de chaînes de télévision composé de Universal Channel, Syfy, 13th Street, Studio Universal, E!, The Style Network, DIVA Universal, et Telemundo, une société de production cinématographique ainsi que des maisons de production d’émissions TV et des parcs à thèmes de renommée mondiale. -

Problems of Tempo in Puccini's Operas

Problems of Tempo in Puccini's Arias Author(s): Mei Zhong Source: College Music Symposium, Vol. 40 (2000), pp. 140-150 Published by: College Music Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374404 Accessed: 22-08-2018 17:38 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms College Music Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College Music Symposium This content downloaded from 129.105.215.146 on Wed, 22 Aug 2018 17:38:20 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Problems of Tempo in Puccini's Arias Mei Zhong problems of tempo in Puccini's soprano arias are surprisingly vexing for per- formers, given that the composer provided many indications in his scores, including many metronome markings, and supervised the preparation of several singers who went on to make early phonograph recordings of his arias. The difficulties arise from the lack of markings in some cases, ambiguous or impractical markings in others (with some evidence that at times Puccini himself was not reliable in this matter), doubts about the authorship of some markings, and wide variations in tempo among recorded perfor- mances. -

SEC News Digest, 11-15-1999

l ./ SEC NEWS DIGEST Issue 99-219 November IS, 1999 SELF-REGULATORY ORGANIZATIONS IMMEDIATE EFFECTIVENESS OF PROPOSED RULE CHANGES A proposed rule change filed by the Philadelphia Stock Exchange amending rules governing the Phlx Automatic Communication and Execution System (SR-Phlx-99-33) has become effective under Section 19{b) (3) (A) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Publication of the proposal is expected in the Federal Register during the week of November 15. (ReI. 34-42120) A proposed rule change filed by the Philadelphia Stock Exchange (SR- Phlx-99-34) to amend its fee schedule for Registered Representative registration has become effective under Section 19{b) (3) (A) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Publication of the proposal is expected in the Federal Register during the week of November 15. (ReI. 34-42122) A proposed rule change filed by the Philadelphia Stock Exchange (SR- Phlx-99-37) to increase the maximum size of option orders eligible for delivery through the Automated Options Market System (AUTOM) has become effective under Section 19{b) (3) (A) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Publication of the proposal is expected in the Federal Register during the week of November 15. (ReI. 34- 42123 ) The American Stock Exchange, Pacific Exchange, and the Chicago Board Options Exchange have filed proposed rule changes (SR-Amex-99-40i SR-PCX-99-41i SR-CBOE-99-59) to make permanent pilot programs eliminating position and exercise limits for FLEX Equity options. Publication of the proposal is expected in the Federal Register during the week of November 15. -

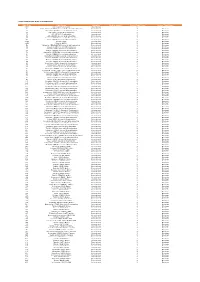

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

Iasa-Phonographic-Bulletin-4.Pdf

EDITORIAL Thanks to the co-operation of four of our members this issue of the Phonographic Bulletin brings together articles about various sound archives from various countries: Germany, France, Australia and The Netherlands. It is therefore typical of IASA, being an association which tries "to strengthen the bonds of co-operation between archives which preserve documents of recorded sound". There is also a supplement on the list of members (who already paid their dues!) as published in the preceding Bulletin. R.L. Schuursma secretary -2- SOME INFORMATION ON SOUND ARCHIVES IN AUSTRALIA Peter Burgis, Consultant on Sound Recordings, National Library of Australia. The earliest known surviving sound recordings preserved in Australia are a set of three wax cylinder phonograph recordings made by Mrs. Fanny Cochrane Smith (1 8 33- 1905), claimed to be one of the last full-blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals, who was recorded in Hobart by the Royal Society of Tasmania on August 5th, 1899 ~ These recordings are held by the Tasmanian Museum who have dubbed them on to a 7" extended play microgroove recording, together with later 1903 cylindrical recordings by Mrs. Smith. In March and April 1901 the famous anthropologist (Sir) Charles Baldwin Spencer made phonograph recordings of Aborigin~l singing at camps at Stevenson i s Creek (South Australia) and Charlotte Waters (Northern Territory). Of 36 cylinders made by Spencer on these trips only 15 survive, many being destroyed in the return camel tripG Spencer ventured to the Northern Territory again in October and November 1912 and 26 recor dings survive, preserved in the National Museum of Victoria. -

Programme Planning Scheduling Intern

UNIVERSAL NETWORKS INTERNATIONAL 6TH FLOOR, PROSPECT HOUSE 80-110 NEW OXFORD STREET LONDON WC1A 1HB ABOUT US Universal Networks International is part of NBC UNIVERSAL one of the world's leading media and entertainment companies in the development, production and marketing of entertainment, news and information to a global audience. It owns and operates the distinct entertainment channels Sci Fi, 13th Street, Studio Universal, Universal Channel, Hallmark Channel, Movies 24, Diva TV and an interest in the KidsCo joint venture. Collectively, these channels reach more than 130 million households across Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Australia, Latin America and Asia. NBC Universal is 80% owned by General Electric and 20% owned by Vivendi. ABOUT THE ROLE Programme Planning & Scheduling Intern This is a very unique opportunity for you to get involved with a prestigious media and entertainment company, based in the heart of London! You will improve both your personal and language skills and get a first, real work experience in the multicultural, corporate environment. Internship description: supervised by our 2 Head of Planning for the channels in Central & Eastern Europe, Russia, Benelux and Africa, your job will be to put eye-catching PowerPoint presentations together, select tv movies from availabilities lists and catalogue, view tv movies screeners (yes, that’s the fun part! ☺) and write appropriate reports and recommendations for buying, help inputting the schedules into the broadcast systems. Requirements: - with a good command of English,