Problems of Tempo in Puccini's Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

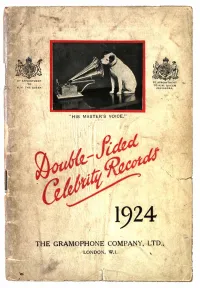

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

August 1935) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1935 Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935)." , (1935). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/836 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE AUGUST 1935 PAGE 441 Instrumental rr Ensemble Music easy QUARTETS !£=;= THE BRASS CHOIR A COLLECTION FOR BRASS INSTRUMENTS , saptc PUBLISHED FOR ar”!S.""c-.ss;v' mmizm HIM The well ^uiPJ^^at^Jrui^“P-a0[a^ L DAY IN VE JhEODORE pRESSER ^O. DIRECT-MAIL SERVICE ON EVERYTHING IN MUSIC PUBLICATIONS * A Editor JAMES FRANCIS COOKE THE ETUDE Associate Editor EDWARD ELLSWORTH HIPSHER Published Monthly By Music Magazine THEODORE PRESSER CO. 1712 Chestnut Street A monthly journal for teachers, students and all lovers OF music PHILADELPHIA, PENNA. VOL. LIIINo. 8 • AUGUST, 1935 The World of Music Interesting and Important Items Gleaned in a Constant Watch on Happenings and Activities Pertaining to Things Musical Everyw er THE “STABAT NINA HAGERUP GRIEG, widow of MATER” of Dr. -

1 Madama Butterfly I Personaggi E Gli Interpreti

1 G V M e i r a a s i d c o n o a e Madama Butterfly m m o o r a i Versione originale del 17 febbraio 1904 g i P B n u a u l c Giacomo Puccini e t c t d e i e n r l i f 1 l 7 y f e Stagione d’Opera 2016 / 2017 b b r a i o 1 9 0 4 S t a g i o n e d ’ O p e r a 2 0 1 6 / 2 0 1 7 Madama Butterfly Versione originale del 17 febbraio 1904 Tragedia giapponese in due atti Musica di Giacomo Puccini Libretto di Luigi Illica e Giuseppe Giacosa (da John L. Long e David Belasco) Nuova produzione Teatro alla Scala EDIZIONI DEL TEATRO ALLA SCALA TEATRO ALLA SCALA PRIMA RAPPRESENTAZIONE Mercoledì 7 dicembre 2016, ore 18 REPLICHE dicembre Sabato 10 Ore 20 – TurNo B Martedì 13 Ore 20 – TurNo A VeNerdì 16 Ore 20 – TurNo C DomeNica 18 Ore 20 – TurNo D VeNerdì 23 Ore 20 – TurNo E REPLICHE gennaio 2017 Martedì 3 Ore 20 – Fuori abboNameNto DomeNica 8 Ore 15 – Fuori abboNameNto ANteprima dedicata ai GiovaNi LaScalaUNDER30 Domenica 4 dicembre 2016, ore 18 SOMMARIO 5 Madama Butterfly . Il libretto 40 Il soggetto ArgumeNt – SyNopsis – Die HaNdluNg – ࠶ࡽࡍࡌ – Сюжет Claudio Toscani 53 Giacomo PucciNi Marco Mattarozzi 56 L’opera iN breve Claudio Toscani 58 La musica Virgilio Bernardoni 62 La prima Butterfly , uN ricoNoscimeNto morale all’Autore. UNa possibilità iN più di ascolto, coNfroNto e coNosceNza INtervista a Riccardo Chailly 67 “UNa vera sposa...”? INgaNNo e illusioNe Nella prima Arthur Groos scaligera di Madama Butterfly 83 Madama Butterfly, uNa tragedia iN kimoNo Michele Girardi 99 Come eseguire Madama Butterfly Dieter Schickling 110 Madama Butterfly alla Scala dal 1904 al 2007 Luca Chierici 137 Alvis HermaNis e Madama Butterfly Olivier Lexa Il gesto della fragilità 167 Riccardo Chailly 169 Alvis HermaNis 170 Leila Fteita 171 Kris t¯ıNe Jur j¯aNe 172 Gleb FilshtiNsky 173 INeta SipuNova 174 Alla Sigalova 175 Olivier Lexa 176 Madama Butterfly . -

10-26-2019 Manon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET manon conductor Opera in five acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe production Laurent Pelly Gille, based on the novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut set designer Chantal Thomas by Abbé Antoine-François Prévost costume designer Saturday, October 26, 2019 Laurent Pelly 1:00–5:05PM lighting designer Joël Adam Last time this season choreographer Lionel Hoche revival stage director The production of Manon was Christian Räth made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb Manon is a co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse 2019–20 SEASON The 279th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S manon conductor Maurizio Benini in order of vocal appearance guillot de morfontaine manon lescaut Carlo Bosi Lisette Oropesa* de brétigny chevalier des grieux Brett Polegato Michael Fabiano pousset te a maid Jacqueline Echols Edyta Kulczak javot te comte des grieux Laura Krumm Kwangchul Youn roset te Maya Lahyani an innkeeper Paul Corona lescaut Artur Ruciński guards Mario Bahg** Jeongcheol Cha Saturday, October 26, 2019, 1:00–5:05PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Digital support of The Met: Live in HD is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. The Met: Live in HD series is supported by Rolex. -

Carmen: the Complete Opera Free

FREE CARMEN: THE COMPLETE OPERA PDF Georges Bizet,Clinical Professor at the College of Medicine William Berger MD,David Foil | 144 pages | 15 Dec 2005 | Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers Inc | 9781579125080 | English | New York, United States Complete Opera (Carmen) by G. Bizet - free download on MusicaNeo Sheet music file Free. Sheet music file 4. Sheet music file 1. Sheet music file Sheet music file including a license for an unlimited number of performances, limited to one year. Read license 1. Sheet music file 7. Upload Sheet Music. Publish Sheet Music. En De Ru Pt. Georges Bizet. Piano score. Look inside. Sheet music file Free Uploader Library. PDF, Arrangement for piano solo of the opera "Carmen" written by Bizet. If you have any question don't hesitate to contact us at olcbarcelonamusic gmail. Act I. Act II. Act III. Act IV. PDF, 8. Act II No. Act III No. PDF, 9. Act IV No. PDF, 5. Act I, Piano-vocal score. Act II, Piano-vocal score. Act III, Piano-vocal score. Piano-vocal score. Act IV, Piano-vocal score. Overture and Act I. PDF, 2. Overture, for sextet, Op. PDF, 1. Overture, for piano four hands. Overture, for piano. Entr'acte to Act IV, for string quartet. Orchestral harp part. Orchestral Harp. Orchestral cello part. PDF, 4. Orchestral part of Celli. Orchestral contrabasses part. Orchestral part of Contrabasses. Orchestral violin I part. Orchestral Violin I. Orchestral violin II part. Orchestral parts of Violini Carmen: The Complete Opera. Orchestral viola part. Carmen: The Complete Opera part of Viola. Orchestral clarinet I part. -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

20 Eine Unvergessene Stimme Aus Dresden Elfride Trötschel Singt Reger

20 Eine unvergessene Stimme aus Dresden Elfride Trötschel singt Reger Das Leben der begnadeten Sängerin Elfride Trötschel beginnt 1913 in Dresden und endet 1958 in Berlin. Schon im Alter von acht Jahren verlor sie ihre beiden Eltern. Ihre große musikalische Begabung muss früh festgestellt worden sein. Die erste sängerische Ausbildung erfuhr sie durch den Dresdner Bass-Bariton Paul Schöffer, die weitere Ausbildung über- nahm die Dresdner Altistin Helene Jung, die in drei Uraufführungen von Richard Strauss an der Semperoper mitgewirkt hatte. Jung förderte Trötschels hohen So- pran und zog ihre Stimme nicht in die Tiefe der Altstimme, wie es Elisabeth Schwarz- kopf passiert ist. Bereits 1934 hatte Elfri- de Trötschel ihr erstes Soloengagement an der Dresdner Oper unter Karl Böhm. Damals wurden Karrieren in den großen Opernensembles behutsam angegangen, so dass die Stimme nie überfordert wurde Elfride Trötschel am Flügel, 1953 und in Ruhe reifen konnte. Das Dresdner Publikum liebte Elfride Trötschel ganz besonders und vergaß sie auch dann nicht, als sie nach Berlin ging. Immer wieder kam sie für Gastspiele nach Dresden, wo sie bis heute hoch verehrt wird und sogar eine Straße nach ihr benannt ist. Warum aber ist das so? Dies hat mehrere Gründe: Zum einen war sie ein Dresdner Kind und ihr Aufstieg vom Chor zur Solistin der Staatsoper wurde von den Opernfreunden genau verfolgt. Andererseits ist ihre Stimme durch die Feinheit ihres Vortrags und die Leuchtkraft ihres Timbres charakterisiert, wie das Sängerlexikon von Kutsch/Riemens ausführt. Sie ist wie alle großen Sängerinnen schon nach we- nigen Takten an ihrem Stimmklang zu erkennen. Die Fotografen zeigen eine expressive Darstellerin von großer weiblicher Ausstrahlung. -

Bellini's Norma

Bellini’s Norma - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore There are around 130 recordings of Norma in the catalogue of which only ten were made in the studio. The penultimate version of those was made as long as thirty-five years ago, then, after a long gap, Cecilia Bartoli made a new recording between 2011 and 2013 which is really hors concours for reasons which I elaborate in my review below. The comparative scarcity of studio accounts is partially explained by the difficulty of casting the eponymous role, which epitomises bel canto style yet also lends itself to verismo interpretation, requiring a vocalist of supreme ability and versatility. Its challenges have thus been essayed by the greatest sopranos in history, beginning with Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in 1831. Subsequent famous exponents include Maria Malibran, Jenny Lind and Lilli Lehmann in the nineteenth century, through to Claudia Muzio, Rosa Ponselle and Gina Cigna in the first part of the twentieth. Maria Callas, then Joan Sutherland, dominated the role post-war; both performed it frequently and each made two bench-mark studio recordings. Callas in particular is to this day identified with Norma alongside Tosca; she performed it on stage over eighty times and her interpretation casts a long shadow over. Artists since, such as Gencer, Caballé, Scotto, Sills, and, more recently, Sondra Radvanovsky have had success with it, but none has really challenged the supremacy of Callas and Sutherland. Now that the age of expensive studio opera recordings is largely over in favour of recording live or concert performances, and given that there seemed to be little commercial or artistic rationale for producing another recording to challenge those already in the catalogue, the appearance of the new Bartoli recording was a surprise, but it sought to justify its existence via the claim that it authentically reinstates the integrity of Bellini’s original concept in matters such as voice categories, ornamentation and instrumentation. -

![[T] IMRE PALLÓ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/t-imre-pall%C3%B3-725305.webp)

[T] IMRE PALLÓ

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs FRANZ (FRANTISEK) PÁCAL [t]. Leitomischi, Austria, 1865-Nepomuk, Czechoslo- vakia, 1938. First an orchestral violinist, Pácal then studied voice with Gustav Walter in Vienna and sang as a chorister in Cologne, Bremen and Graz. In 1895 he became a member of the Vienna Hofoper and had a great success there in 1897 singing the small role of the Fisherman in Rossini’s William Tell. He then was promoted to leading roles and remained in Vienna through 1905. Unfor- tunately he and the Opera’s director, Gustav Mahler, didn’t get along, despite Pacal having instructed his son to kiss Mahler’s hand in public (behavior Mahler considered obsequious). Pacal stated that Mahler ruined his career, calling him “talentless” and “humiliating me in front of all the Opera personnel.” We don’t know what happened to invoke Mahler’s wrath but we do know that Pácal sent Mahler a letter in 1906, unsuccessfully begging for another chance. Leaving Vienna, Pácal then sang with the Prague National Opera, in Riga and finally in Posen. His rare records demonstate a fine voice with considerable ring in the upper register. -Internet sources 1858. 10” Blk. Wien G&T 43832 [891x-Do-2z]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker). Very tiny rim chip blank side only. Very fine copy, just about 2. $60.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. -

The Making of Disgrace Kelly: Dragging the Diva Through Cabarets, Pubs and Into the Recital Hall

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2013 The making of Disgrace Kelly: Dragging the diva through cabarets, pubs and Into the recital hall Caitlin Cassidy Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cassidy, C. (2013). The making of Disgrace Kelly: Dragging the diva through cabarets, pubs and Into the recital hall. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/545 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/545 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

El Camino De Verdi Al Verismo: La Gioconda De Ponchielli the Road of Verdi to Verism: La Gioconda De Ponchielli

Revista AV Notas, Nº8 ISSN: 2529-8577 Diciembre, 2019 EL CAMINO DE VERDI AL VERISMO: LA GIOCONDA DE PONCHIELLI THE ROAD OF VERDI TO VERISM: LA GIOCONDA DE PONCHIELLI Joaquín Piñeiro Blanca Universidad de Cádiz RESUMEN Con Giuseppe Verdi se amplificaron y superaron los límites del Bel Canto representado, fundamentalmente, por Rossini, Bellini y Donizetti. Se abrieron nuevos caminos para la lírica italiana y en la evolución que terminaría derivando en la eclosión del Verismo que se articuló en torno a una nutrida generación de autores como Leoncavallo, Mascagni o Puccini. Entre Verdi y la Giovane Scuola se situaron algunos compositores que constituyeron un puente entre ambos momentos creativos. Entre ellos destacó Amilcare Ponchielli (1834-1886), profesor de algunos de los músicos más destacados del Verismo y autor de una de las óperas más influyentes del momento: La Gioconda (1876-1880), estudiada en este artículo en sus singularidades formales y de contenido que, en varios aspectos, hacen que se adelante al modelo teórico verista. Por otra parte, se estudian también cuáles son los elementos que conserva de los compositores italianos precedentes y las influencias del modelo estético francés, lo que determina que la obra y su compositor sean de complicada clasificación, aunque habitualmente se le identifique incorrectamente con el Verismo. Palabras clave: Ponchielli; Verismo; Giovane Scuola; ópera; La Gioconda; Italia ABSTRACT With Giuseppe Verdi, the boundaries of Bel Canto were amplified and exceeded, mainly represented by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. New paths were opened for the Italian lyric and in the evolution that would end up leading to the emergence of Verismo that was articulated around a large generation of authors such as Leoncavallo, Mascagni or Puccini.