Breeding Success of Eeding Success of Cacicus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auto Guia Version Ingles

Parque Natural Metropolitano Tel: (507) 232-5516/5552 Fax: (507) 232-5615 www.parquemetropolitano.org Ave. Juan Pablo II final P.O. Box 0843-03129 Balboa, Ancón, Panamá República de Panamá 2 Taylor, L. 2006. Raintree Nutrition, Tropical Plant Database. http://www.rain- Welcome to the Metropolitan Natural Park, the lungs of Panama tree.com/plist.htm. Date accessed; February 2007 City! The park was established in 1985 and contains 232 hectares. It is one of the few protected areas located within the city border. Thomson, L., & Evans, B. 2006. Terminalia catappa (tropical almond), Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources You are about to enter an ecosystem that is nearly extinct in Latin (PAR), Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). http://www.traditionaltreeorg . Date accessed March America: the Pacific dry forests. Whether your goals for this walk 2007-04-23 are a simple walk to keep you in shape or a careful look at the forest and its inhabitants, this guide will give you information about Young, A., Myers, P., Byrne, A. 1999, 2001, 2004. Bradypus variegatus, what can be commonly seen. We want to draw your attention Megalonychidae, Atta sexdens, Animal Diversity Web. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Bradypus_var toward little things that may at first glance seem hidden away. Our iegatus.html. Date accessed March 2007 hope is that it will raise your curiosity and that you’ll want to learn more about the mysteries that lie within the tropical forest. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The contents of this book include tree identifications, introductions Text and design: Elisabeth Naud and Rudi Markgraf, McGill University, to basic ecological concepts and special facts about animals you Montreal, Canada. -

Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & EAST ANDEAN FOOTHILLS EXTENSION

Tropical Birding Trip Report Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & East Andean Foothills Extension (Jan-Feb 2021) A Tropical Birding custom extension Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & EAST ANDEAN FOOTHILLS EXTENSION th nd 27 January - 2 February 2021 The main motivation for this custom extension was this Harpy Eagle. This was one of an unusually accessible nesting pair near the Amazonian town of Limoncocha that provided a worthy add-on to The Andes Introtour in northwest Ecuador that preceded this (Jose Illanes/Tropical Birding Tours). Guided by Jose Illanes Birds in the photos within this report are denoted in RED, all photos were taken by the Tropical Birding guide. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Ecuador: HARPY EAGLE & East Andean Foothills Extension (Jan-Feb 2021) INTRODUCTION This custom extension trip was set up for one person who simply could not get enough of Ecuador…John had just finished Ecuador: The Andes Introtour, in the northwest of the country, and also joined the High Andes Extension to that tour, which sampled the eastern highlands too. However, he was still missing vast chunks of this small country that is bursting with bird diversity. Most importantly, he was keen to get in on the latest “mega bird” in Ecuador, a very accessible Harpy Eagle nest, near a small Amazonian town, which had been hitting the local headlines and drawing the few birding tourists in the country at this time to come see it. With this in mind, TROPICAL BIRDING has been offering custom add-ons to all of our Ecuador offerings (for 2021 and 2022) to see this Harpy Eagle pair, with only three extra days needed to see it. -

Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018

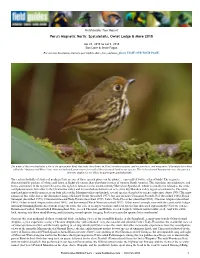

Field Guides Tour Report Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018 Jun 23, 2018 to Jul 5, 2018 Dan Lane & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The name of this tour highlights a few of the spectacular birds that make their homes in Peru's northern regions, and we saw these, and many more! This might have been called the "Antpittas and More" tour, since we had such great views of several of these formerly hard-to-see species. This Ochre-fronted Antpitta was one; she put on a fantastic display for us! Photo by participant Linda Rudolph. The eastern foothills of Andes of northern Peru are one of those special places on the planet… especially if you’re a fan of birds! The region is characterized by pockets of white sand forest at higher elevations than elsewhere in most of western South America. This translates into endemism, and hence our interest in the region! Of course, the region is famous for the award-winning Marvelous Spatuletail, which is actually not related to the white sand phenomenon, but rather to the Utcubamba valley and its rainshadow habitats (an arm of the dry Marañon valley region of endemism). The white sand endemics actually span areas on both sides of the Marañon valley and include several species described to science only since about 1976! The most famous of this collection is the diminutive Long-whiskered Owlet (described 1977), but also includes Cinnamon Screech-Owl (described 1986), Royal Sunangel (described 1979), Cinnamon-breasted Tody-Tyrant (described 1979), Lulu’s Tody-Flycatcher (described 2001), Chestnut Antpitta (described 1987), Ochre-fronted Antpitta (described 1983), and Bar-winged Wood-Wren (described 1977). -

Chapter One: Introduction

Nocturnal Adventures Curriculum Manual 2013 Updated by Kimberly Mosgrove 3/28/2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION……………………………………….……….…………………… pp. 3-4 CHAPTER 2: THE NUTS AND BOLTS………………………………………….……………….pp. 5-10 CHAPTER 3: POLICIES…………………………………………………………………………………….p. 11 CHAPTER 4: EMERGENCY PROCEDURES……………..……………………….………….pp. 12-13 CHAPTER 5: GENERAL PROGRAM INFORMATION………………………….………..pp.14-17 CHAPTER 6: OVERNIGHT TOURS I - Animal Adaptations………………………….pp. 18-50 CHAPTER 7: OVERNIGHT TOURS II - Sleep with the Manatees………..………pp. 51-81 CHAPTER 8: OVERNIGHT TOURS III - Wolf Woods…………….………….….….pp. 82-127 CHAPTER 9: MORNING TOURS…………………………………………………………….pp.128-130 Updated by Kimberly Mosgrove 3/28/2013 2 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION What is the Nocturnal Adventures program? The Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Education Department offers a unique look at our zoo—the zoo at night. We offer three sequential overnight programs designed to build upon students’ understanding of the natural world. Within these programs, we strive to combine learning with curiosity, passion with dedication, and advocacy with perspective. By sharing our knowledge of, and excitement about, environmental education, we hope to create quality experiences that foster a sense of wonder, share knowledge, and advocate active involvement with wildlife and wild places. Overnight experiences offer a deeper and more profound look at what a zoo really is. The children involved have time to process what they experience, while encountering firsthand the wonderful relationships people can have with wild animals and wild places. The program offers three special adventures: Animal Adaptations, Wolf Woods, and Sleep with the Manatees, including several specialty programs. Activities range from a guided tour of zoo buildings and grounds (including a peek behind-the-scenes), to educational games, animal demonstrations, late night hikes, and presentations of bio-facts. -

Isospora Guaxi N. Sp. and Isosp

Syst Parasitol (2017) 94:151–157 DOI 10.1007/s11230-016-9688-y Some remarks on the distribution and dispersion of Coccidia from icterid birds in South America: Isospora guaxi n. sp. and Isospora bellicosa Upton, Stamper & Whitaker, 1995 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the red-rumped cacique Cacicus haemorrhous (L.) (Passeriformes: Icteridae) in southeastern Brazil Lidiane Maria da Silva . Mariana Borges Rodrigues . Irlane Faria de Pinho . Bruno do Bomfim Lopes . Hermes Ribeiro Luz . Ildemar Ferreira . Carlos Wilson Gomes Lopes . Bruno Pereira Berto Received: 27 May 2016 / Accepted: 19 November 2016 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 Abstract A new species of coccidian, Isospora guaxi residuum are absent, but a polar granule is present. n. sp., and Isospora bellicosa Upton, Stamper & Sporocysts are ellipsoidal, measuring on average Whitaker, 1995 (Protozoa: Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) 19.3 9 13.8 lm. Stieda body is knob-like and sub- are recorded from red-rumped caciques Cacicus haem- Stieda body is prominent and compartmentalized. orrhous (L.) in the Parque Nacional do Itatiaia, Brazil. Sporocyst residuum is composed of scattered granules. Isospora guaxi n. sp. has sub-spheroidal oo¨cysts, mea- Sporozoites are vermiform, with one refractile body and suring on average 30.9 9 29.0 lm, with smooth, bi- anucleus.Isospora bellicosa has sub-spheroidal to layered wall c.1.9 lm thick. Micropyle and oo¨cyst ovoidal oo¨cysts, measuring on average 27.1 9 25.0 lm, with smooth, bi-layered wall c.1.5 lm thick. Micropyle and oo¨cyst residuum are absent, but one or two polar L. M. da Silva Á M. -

Cockroaches ¡N French Guiana Icteridae Birds Nests

AMAZONIANA XVII ( l/2): 243-248 Kiel. Dezember 2002 Cockroaches ¡n French Guiana Icteridae birds nests by J. van Baaren, P. Deleporte & P. Grandcolas Dr. Joan van Baaren, UMR 6552, Ethologie Evolution Ecologie, Université de Rennes I, Campus de Beaulieu, Avenue du Général Leclerc, 35042 Rennes Cedex" France; e- mail: [email protected] Dr. P. Deleporte, UMR 6552, Ethologie Evolution Ecologie, Station Biologique de Paimpont, 35380 Paimpont, France; e-mail: [email protected] Dr. P. Grandcolas, ESA 8043 CNRS, Laboratoire d'Entomologie, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, 45 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France; e-mail: pg@mnhn"fr (Accepted for publication: July, 2001 ). Abstract We present here the cockroaches found rn 55 nests of Icferidae birds in French Guiana in July I 998. Five species of cockroaches were found, Schultesia nitor (Zetoborinae), Phoetaliu pcl1lrla (Blaberinae), Pelmatosilpha guianae (Blattinae), Chorisoneura n.sp. aff. gutunae (Pseudophyllodromiidae) and Epilum- pra griseo (Epilamprinae). The two dominant species, S nitor and P. pallida, were f'ound together in the same nests, and seem to be scavengers. The ecology of S. nitor was compared with those o{ S. lontp.rri- difonnis, a sister species found in the same type ofhabitat in Brazil. Key words: Bird nest, cockroach, Schultesia, Zetoborinae, Phoetøliø, Blaberinae. Resumo Apresentamos aqui as baratas encontradas em 55 ninhos de pássaros lcteridae na Guiana Francesa em Ji¡lho de 1998. Cinco espécies de baratas foram encontradas: Schultesia nitor (Zetoborinae), Phoetuliu pullida (Blaberinae), Pelmato.silpha guianae (Blattinae), Chorisoneut'a n.sp. aff . gotnnue (Pseudophyllodromiidae) e Epilantpra griseo (Epilamprinae). As duas espécies dominantes, S. -

Seasonality and Elevational Migration in an Andean Bird Community

SEASONALITY AND ELEVATIONAL MIGRATION IN AN ANDEAN BIRD COMMUNITY _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CHRISTOPHER L. MERKORD Dr. John Faaborg, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2010 © Copyright by Christopher L. Merkord 2010 All Rights reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled ELEVATIONAL MIGRATION OF BIRDS ON THE EASTERN SLOPE OF THE ANDES IN SOUTHEASTERN PERU presented by Christopher L. Merkord, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John Faaborg Professor James Carrel Professor Raymond Semlitsch Professor Frank Thompson Professor Miles Silman For mom and dad… ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was completed with the mentoring, guidance, support, advice, enthusiasm, dedication, and collaboration of a great many people. Each chapter has its own acknowledgments, but here I want to mention the people who helped bring this dissertation together as a whole. First and foremost my parents, for raising me outdoors, hosting an endless stream of squirrels, snakes, lizards, turtles, fish, birds, and other pets, passing on their 20-year old Spacemaster spotting scope, showing me every natural ecosystem within a three day drive, taking me on my first trip to the tropics, putting up with all manner of trouble I’ve gotten myself into while pursuing my dreams, and for offering my their constant love and support. Tony Ortiz, for helping me while away the hours, and for sharing with me his sense of humor. -

Predators of Bird Nests in the Atlantic Forest of Argentina and Paraguay Author(S): Kristina L

Predators of bird nests in the Atlantic forest of Argentina and Paraguay Author(s): Kristina L. Cockle, Alejandro Bodrati, Martjan Lammertink, Eugenia Bianca Bonaparte, Carlos Ferreyra, and Facundo G. Di Sallo Source: The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 128(1):120-131. Published By: The Wilson Ornithological Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1676/wils-128-01-120-131.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1676/wils-128-01-120-131.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 128(1):120–131, 2016 PREDATORS OF BIRD NESTS IN THE ATLANTIC FOREST OF ARGENTINA AND PARAGUAY KRISTINA L. COCKLE,1,2,3,6,7 ALEJANDRO BODRATI,2 MARTJAN LAMMERTINK,2,4,5 EUGENIA BIANCA BONAPARTE,2 CARLOS FERREYRA,2 AND FACUNDO G. DI SALLO2 ABSTRACT.—Predation is the major cause of avian nest failure, and an important source of natural selection on life history traits and reproductive behavior. -

8-11 Yr. Old Full Day Summer Camp Expedition Naturalist

8-11 yr. Old Full Day Summer Camp Expedition Naturalist At a glance Campers will discover the globes diverse plant and animal life. Campers will explore ecological processes on each adventure in the world’s different biomes Time requirement 7hrs./day Group size and grade(s) 5-12 kids/instructor Materials Goal(s) -Campers should discover the world’s different biomes and their interconnectedness -Campers should understand general ecological concepts- feeding strategies, biotic and abiotic features in systems -Campers should appreciate the world’s plant and animal diversity -Campers should want to protect these wonderful places on earth Objective(s) 1. Participants will be able to name at least 5 types of feeding strategies (herbivory, carnivory, frugivory, saugivory…) 2. Campers will be able to define a food web (autotrophs, primary and secondary consumers) 3. Campers will be able to locate the worlds biomes- on a world map Theme -Leave with an understanding of the worlds diversity of biomes and the diversity of animals and plants that live in them 1. There should be five or fewer. Choose Your Own Adventure: Expedition Naturalist, Summer 2011 Page 1 of 74 Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden Expedition Naturalist Summer Camp 2011 Day I- Expedition Aquatic -*ALL ANIMALS ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE FOR ANIMAL DEMOS- -*ONE SNACK WILL BE GIVEN/ DAY YOU WILL DISTURBUTE AT YOUR OWN DESCRETION- -*IN BETWEEN NIGHT HUNTERS & MONKEY ISLAND—THERE IS A MIST TUNNEL—GO AND CHILL OUT AT POINTS THRU OUT THE DAY. -*FEEL FREE TO ADD IN ANCILLARY DETAILS Use the train, tram to move through the zoo whenever possible or to just relax. -

Evidence for Giant Cowbird Molothrus Oryzivorus Brood-Parasitism Of

Cotinga 27 Evidence for Giant Cowbird Molothrus oryzivorus brood-parasitism of Turquoise Jays Cyanolyca turcosa in north-west Ecuador, and how this alters our understanding of cowbird brood parasitism Mark Welford, Andrés Vásquez, Paúl Sambrano, Tony Nunnery and Barry Ulman Received 20 September 2005; final revision accepted 1 August 2006 Cotinga 27 (2007): 58–60 Sortee las observaciones del valle de Tandayapa, Ecuador, proporciona la primera evidencia de parasitismo exitoso de cría de corvids (es decir, los Urraca Turquesa Cyanolyca turcosa) por Vaquero Gigante Molothrus oryzivorus. Estos datos sugieren que en el extremo de su gama de altitudinal Vaquero Gigante es más flexible en su elección de anfitrión de cría que pensó previamente. Giant Cowbirds Molothrus oryzivorus are abundant in eastern Ecuador, but less common in the west12 and are occasionally observed as high as 2,000 m12. The species is considered a brood-host specialist: it parasitises seven cacique Cacicus and oropendola Psarocolius species3,5,14 and has never, to our knowledge, parasitised any corvid. In contrast, Ortega10 considered three other parasitic cowbirds Molothrus aeneus, M. bonariensis and M. ater brood-host generalists. Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater is known to have parasitised 226 host species3,10. Thus, when two Turquoise Jays Cyanolyca turcosa were observed at Bellavista Lodge, on the old Nono–Mindo Road, in western Ecuador, at 2,250 m, feeding two highly vocal (audible up to 100 m away) and aggressive Giant Cowbird fledglings in late May 2005, by MW, the initial identification was regarded as tentative. Subsequent discussion with AV, PS (both guides at Bellavista Lodge) and TN confirmed the identifica- tion. -

Juan Carlos Reboreda Vanina Dafne Fiorini · Diego Tomás Tuero Editors

Juan Carlos Reboreda Vanina Dafne Fiorini · Diego Tomás Tuero Editors Behavioral Ecology of Neotropical Birds Chapter 6 Obligate Brood Parasitism on Neotropical Birds Vanina Dafne Fiorini , María C. De Mársico, Cynthia A. Ursino, and Juan Carlos Reboreda 6.1 Introduction Obligate brood parasites do not build their nests nor do feed and take care of their nestlings. Instead, they lay their eggs in nests of individuals of other species (hosts) that rear the parasitic progeny. For behavioral ecologists interested in coevolution, obligate brood parasites are pearls of the avian world. These species represent only 1% of all the living avian species, and their peculiar reproductive strategy imposes on them permanent challenges for successful reproduction. At the same time, the hosts are under strong selective pressures to reduce the costs associated with para- sitism, such as the destruction of eggs by parasitic females and the potential fitness costs of rearing foreign nestlings. These selective pressures may result in parasites and hosts entering in a coevolutionary arms race, in which a broad range of defenses and counterdefenses can evolve. Females of most species of parasites have evolved behaviors such as rapid egg laying and damage of some of the host’s eggs when they visit the nest (Sealy et al. 1995; Soler and Martínez 2000; Fiorini et al. 2014). Reciprocally, as a first line of defense, hosts have evolved the ability to recognize and attack adult parasites (Feeney et al. 2012). Parasitic eggs typically hatch earlier than host eggs decreasing host hatching success and nestling survival (Reboreda et al. 2013), but several host species have evolved recognition and rejection of alien eggs, which in turn selected for the evolution of mimetic eggs in the parasite (Brooke and Davies 1988; Gibbs et al. -

Mixed-Species Bird Flocks in a Mountain Rainforest, Edge Habitat and Cattle Fields in the Ecuadorian Chocó

Mixed-species bird flocks in a mountain rainforest, edge habitat and cattle fields in the Ecuadorian Chocó Maartje Albertine Musschenga Mixed-species bird flocks in a mountain rain forest, edge habitat and cattle fields in the Ecuadorian Chocó region Minor project for the master Environmental Biology, track Behavioural Ecology, Utrecht University. Period: August 2011-July 2012 Author: Maartje Albertine Musschenga, BSc. Student number: 3116913 Supervisors: Nicole Büttner, biological field station ‘Un poco del Chocó’, Pichincha province, Ecuador. Dr. Marie José Duchateau, Behavioural Biology, Utrecht University. Photo cover: the author and another student watching birds in biological reserve ‘Un poco del Chocó’, Pichincha, Ecuador. Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Materials and Methods 7 Results 16 Discussion 37 References 48 Appendices 52 Acknowledgements 57 Abstract Mixed-species flocks are groups consisting of different bird species which travel and forage together. Species in a flock can be divided in nuclear species, which act as a leader or sentinel and attendant species, which follow the nuclear species. In the tropics, their main habitat, flocks are all year round. Tropical forests are threatened by many problems such as invasive settlements, roads and conversion into pastures/agricultural land. These disturbances can affect flocks in various ways. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of disturbance on mixed- species flocks. It was investigated how flocks in three habitats (mountain rain forest, forest edge, cattle fields) in North-west Ecuador differ from each other with respect to composition in niches, number of individuals and species, stability, nuclear and core species. The forest lies in the Chocó eco-region, ranging from Panama to northwest Peru, which is known for its exceptional high biodiversity and endemism.