Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATO and Afghanistan

NATO and Afghanistan NATO led the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan from August 2003 to December 2014. ISAF was deployed at the request of the country’s authorities and mandated by the United Nations. Its mission was to enable the Afghan authorities to provide effective security across the country and ensure that the country would never again be a safe haven for terrorists. ISAF conducted security operations, while also training and developing the Afghan security forces. Following a three-year transition process during which the Afghans gradually took the lead for security across the country, ISAF’s mission was completed at the end of 2014. With that, Afghans assumed full responsibility for security. It is now fully in the hands of the country’s 352,000 soldiers and police, which ISAF helped train over the past years. However, support for the continued development of the Afghan security forces and institutions and wider cooperation with Afghanistan continue. ISAF helped create a secure environment for improving governance and socio-economic development, which are important conditions for sustainable stability. Afghanistan has made the largest percentage gain of any country in basic health and development indicators over the past decade. Maternal mortality is going down and life expectancy is rising. There is a vibrant media scene. Millions of people have exercised their right to vote in five election cycles since 2004, most recently in the 2014 presidential and provincial council elections, which resulted in the establishment of a National Unity Government. While the Afghan security forces have made a lot of progress, they still need international support as they continue to develop. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province by Paul Fishstein ©2012 Feinstein International Center

AUGUST 2012 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice BRIEFING NOTE: Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province by Paul Fishstein ©2012 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image fi les from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 114 Curtis Street Somerville, MA 02144 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fi c.tufts.edu 2 Feinstein International Center Contents I. Summary . 4 II. Study Background . 5 III. Uruzgan Province . 6 A. Geography . 6 B. Short political history of Uruzgan Province . 6 C. The international aid, military, and diplomatic presence in Uruzgan . 7 IV. Findings . .10 A. Confl uence of governance and ethnic factors . .10 B. International military forces . .11 C. Poor distribution and corruption in aid projects . .12 D. Poverty and unemployment . .13 E. Destabilizing effects of aid projects . 14 F. Winning hearts and minds? . .15 V. Final Thoughts and Looking Ahead . .17 Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province 3 I. SUMMARY esearch in Uruzgan suggests that insecurity is largely the result of the failure Rof governance, which has exacerbated traditional tribal rivalries. -

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

Kandahar Survey Report

Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report February 1996 AREA Office 17 - E Abdara Road UfTow Peshawar, Pakistan Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report Prepared by Eng. Yama and Eng. S. Lutfullah Sayed ·• _ ....... "' Content - Introduction ................................. 1 General information on Kandahar: - Summery ........................... 2 - History ........................... 3 - Political situation ............... 5 - Economic .......................... 5 - Population ........................ 6 · - Shelter ..................................... 7 -Cost of labor and construction material ..... 13 -Construction of school buildings ............ 14 -Construction of clinic buildings ............ 20 - Miscellaneous: - SWABAC ............................ 2 4 -Cost of food stuff ................. 24 - House rent· ........................ 2 5 - Travel to Kanadahar ............... 25 Technical recommendation .~ ................. ; .. 26 Introduction: Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan/ AREA intends to undertake some rehabilitation activities in the Kandahar province. In order to properly formulate the project proposals which AREA intends to submit to EC for funding consideration, a general survey of the province has been conducted at the end of Feb. 1996. In line with this objective, two senior staff members of AREA traveled to Kandahar and collect the required information on various aspects of the province. -

Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law — Volume 18, 2015 Correspondents’ Reports

YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW — VOLUME 18, 2015 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS 1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Overview – United States Enforcement of International Humanitarian Law ............................ 1 Cases – United States Federal Court .......................................................................................... 3 Cases – United States Military Courts – Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (CAAF) ...... 4 Cases — United States Military Courts – United States Army ................................................. 4 Cases — United States Military Courts – United States Marine Corps .................................... 5 Issues — United States Department of Defense ........................................................................ 6 Issues — United States Army .................................................................................................... 8 Issues —United States Navy .................................................................................................... 11 Issues — United States Marine Corps ..................................................................................... 12 Overview – United States Detention Practice .......................................................................... 12 Detainee Challenges – United States District Court ................................................................ 13 US Military Commission Appeals ........................................................................................... 16 Court of Appeals for the -

The High Stakes Battle for the Future of Musa Qala

JULY 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 8 The High Stakes Battle for district. This created the standard and treated their presumed supporters in of small landlords farming small, the south better,5 this time there would the Future of Musa Qala well-irrigated holdings. While tribal be no mercy shown to “collaborators.” structure, economy and population alike This included executing, along with By David C. Isby have been badly damaged by decades of alleged criminals, several “spies,” which warfare, Musa Qala has a situation that included Afghans who had taken part in since its reoccupation by NATO and is more likely to yield internal stability work-for-food programs.6 Afghan forces in December 2007, the by building on what is left of traditional remote Musa Qala district of northern Afghanistan. The Alizai are also hoping to get more Helmand Province in Afghanistan from the new security situation. They has become important to the future Before the well-publicized October 2006 have requested that Kabul make Musa course of the insurgency but also to the “truce” that Alizai leaders concluded Qala a separate province.7 This proposal future of a Pashtun tribe (the Alizai), with the Taliban, Musa Qala had has been supported by current and a republic (the Islamic Republic of experienced a broad range of approaches former Helmand provincial governors. Afghanistan) and even a kingdom (the to countering the insurgency. In addition This would provide opportunities for United Kingdom). The changes that to their dissatisfaction with British patronage and give them a legally- take place at Musa Qala will influence operations in 2006, local inhabitants recognized base that competing tribal the future of all of them. -

AFGHANISTAN South

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (25 – 31 January 2021) KEY FIGURES IDPs IN 2021 (AS OF 31 JANUARY) 3,430 People displaced by conflict (verified) 35,610 Received assistance (including 2020 caseload) NATURAL DISASTERS IN 2020 (AS OF 31 JANUARY) 104,470 Number of people affected by natural disasters Conflict incident UNDOCUMENTED RETURNEES Internal displacement IN 2021 (AS OF 21 JANUARY) 36,496 Disruption of services Returnees from Iran 367 Returnees from Pakistan 0 South: Hundreds of people displaced by ongoing Returnees from other countries fighting in Kandahar province HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE Fighting between Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and a non-state armed PLAN (HRP) REQUIREMENTS & group (NSAG) continued in Hilmand, Kandahar and Uruzgan provinces. FUNDING In Kandahar, fighting continued mainly in Arghandab, Zheray and Panjwayi 1.28B districts. Ongoing fighting displaced hundreds of people in Kandahar province, but Requirements (US$) – HRP the exact number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) is yet to be confirmed. 2021 Humanitarian actors with coordination of provincial authorities are assessing the needs of IDPs and will provide them with immediate assistance. Farmers and 37.8M agricultural activities continued to be affected by ongoing fighting. All movements 3% funded (US$) in 2021 on the main highway-1 connecting Hilmand to Kandahar provinces reportedly AFGHANISTAN resumed, however improvised explosive devices (IEDs) along the highway HUMANITARIAN FUND (AHF) continue to pose a threat. 2021 In Uruzgan province, clashes between ANSF and an NSAG continued along with the threat of IED attacks in Dehrawud, Gizab and Tirinkot districts. Two civilians 5.72M were reportedly killed and eight others wounded by an IED detonation in Tirinkot Contributions (US$) district. -

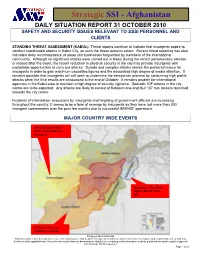

Daily Situation Report 31 October 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 31 OCTOBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced at the end of October. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past few months due to successful IM/ANSF operations. MAJOR COUNTRY WIDE EVENTS Herat: Influencial local Tribal Leader killed by insurgents Nangarhar: Five attacks against Border Police OPs Helmand: Five local residents murdered Privileged and Confidential This information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity to which it is addressed and may contain information that is privileged, confidential, and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Perceptionsjournal of International Affairs

PERCEPTIONSJOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS PERCEPTIONS Winter 2014 Volume XIX Number 4 XIX Number 2014 Volume Winter PERCEPTIONS Locating Turkey as a ‘Rising Power’ in the Changing International Order: An Introduction Emel PARLAR DAL and Gonca OĞUZ GÖK Muslim Perceptions of Injustice as an International Relations Question Hasan KÖSEBALABAN Turkey’s Quest for a “New International Order”: The Discourse of Civilization and the Politics of Restoration Murat YEŞİLTAŞ Tracing the Shift in Turkey’s Normative Approach towards International Order through Debates in the UN Gonca OĞUZ GÖK On Turkey’s Trail as a “Rising Middle Power” in the Network of Global Governance: Preferences, Capabilities, and Strategies Emel PARLAR DAL Transformation Trajectory of the G20 and Turkey’s Presidency: Middle Powers in Global Governance Sadık ÜNAY Jordan and the Arab Spring: Challenges and Opportunities Nuri YEŞİLYURT Post-2014 Drawdown and Afghanistan’s Transition Challenges Saman ZULFQAR Tribute to Ali A. Mazrui M. Akif KAYAPINAR Winter 2014 Volume XIX - Number 4 ISSN 1300-8641 Style and Format PERCEPTIONS Articles submitted to the journal should be original contributions. If another version of the article is under consideration by another publication, or has been or will be published elsewhere, authors should clearly indicate this at the time of submission. Manuscripts should be submitted to: e-mail: [email protected] Editor in Chief The final decision on whether the manuscript is accepted for publication in the Journal or not is made by the Editorial Board depending on the anonymous referees’ review reports. Ali Resul Usul A standard length for PERCEPTIONS articles is 6,000 to 8,000 words including endnotes. -

“They've Shot Many Like This”

HUMAN RIGHTS “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike Forces WATCH “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike Forces Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37779 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37779 “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike Forces Map of Afghanistan ............................................................................................................... i Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ..............................................................................................................